The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America

By Frances FitzGerald

Simon & Schuster, 2017

In the hallway just outside the sanctuary of the midsize Southern Baptist church I grew up in hung a small cork board for posting announcements and other information. Every now and then, someone would pin a voter guide from the Moral Majority or, a few years later, a pamphlet from the Christian Coalition. But most of the time the board filled up with the more pressing concerns of a church body: sign-up sheets for the women’s retreat, the month’s deacon-on-call schedule, pictures from a youth group service project, prayer requests for missionaries in Kenya or the Philippines, an advertisement for a revivalist passing through town.

A hundred years in the future, a historian finding one of those boards preserved from the 1980s or 1990s might thrill at the rich religious lives she could reconstruct from such materials, envisioning more clearly what it meant to be an evangelical in the late twentieth century. Yet the temptation for those writing about evangelicals today is to allow the political part—like the fact that 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump—to stand in for the whole. It is to make the great mistake of reaching only for that Christian Coalition handout tucked into the corner of that cork board in order to account for all of the diversity and variety within a religious tradition to which one in four Americans belong.

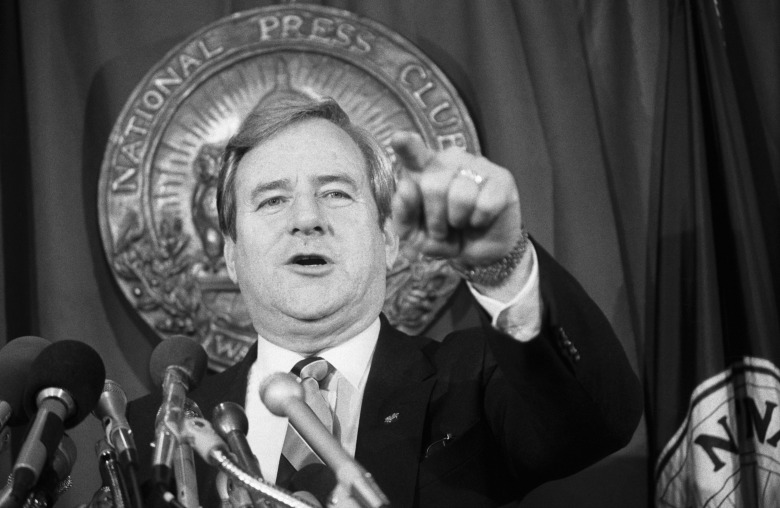

That is the weakness at the heart of the journalist Frances FitzGerald’s new book, The Evangelicals, a sprawling 700-plus page history of the nation’s most important and influential religious movement. FitzGerald, the author of equally massive books on the Vietnam War and the Cold War, has written about evangelicals since the start of the Reagan Administration, beginning with a lengthy New Yorker profile in 1981 of Jerry Falwell, the fundamentalist pastor who became one of the architects of the Christian Right. That starting point has continued to shape FitzGerald’s understanding of American evangelicalism even as she reminds her readers in the opening pages of The Evangelicals that the “category ‘evangelical’ is, of course, not a political but a religious one.”

Yet FitzGerald begins her book, which she tellingly subtitles The Struggle to Shape America, with the story of how during his 1976 run for the presidency, Jimmy Carter, a self-described born-again Christian, sent journalists scrambling to figure out who these evangelicals—some 50 million Americans at the time—were. It was a task made all the more urgent four years later when the Christian Right emerged to lead Reagan to victory. She ends with white evangelicals’ surprising support in 2016 for Trump, the thrice-married casino magnate who ran roughshod over nearly every Christian virtue on his march to the presidency. Both events signaled important developments in American evangelicalism, no doubt. But bookending almost three centuries of evangelical history with two political moments from the last forty years reveals the persistent habit of secular journalists to see evangelicals chiefly as monolithic political actors who only become visible (and relevant) every election cycle.

That history begins with the First Great Awakening, a religious revival that started in Jonathan Edwards’ Northampton, Massachusetts, church in 1734 and spread across New England. As FitzGerald points out, Edwards’ message differed from Puritan leaders of the past and the Congregationalist ministers of his day who had stoked revivals by calling parishioners back to closer adherence to their ministerial authority. Edwards instead preached “the evangelical message that individuals could have a direct relationship with Christ,” a radical message of spiritual autonomy that threatened to topple the religious establishment and upend the social order (which, for most purposes, was the same thing in the 1730s).

The First Great Awakening was soon followed by the Second Great Awakening, a “more explosive” wave of revivals that ebbed and flowed from after the Revolutionary War up to the Civil War. Both revival movements established the evangelical theology of individual regeneration, unleashed ecstatic forms of worship, and imparted an anti-elite, anti-authoritarian ethos and culture among its adherents—all traits of American evangelicalism that have continued up to today. Those beliefs and practices fit well with a developing democracy and flourished particularly among Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians on the expanding frontier of the Midwest and throughout the South.

FitzGerald moves through this history quickly. Less than one-hundred pages in, The Evangelicals arrives in the twentieth century where FitzGerald charts how the “Fundamentalist-Modernist Conflict” split American Protestantism in two. Modernists embraced non-literal interpretations of the Bible, accepted Darwinian evolutionary theory, and advocated a Social Gospel theology of collective reform over individual salvation. In response, fundamentalists drilled down to the essentials—or the fundamentals, in their words—of the faith, drawing up strict doctrinal declarations and redoubling their proselytizing efforts. This conflict played out within various Protestant denominations as both sides battled for control of their church bodies. Modernists ultimately retained their power and the prestigious pulpits, while the fundamentalists broke away to form their own denominations and independent churches. FitzGerald argues that after the embarrassment of the 1925 Scopes trial over the teaching of evolution, fundamentalists further withdrew from American public life, concentrating instead on building up a dense network of Bible colleges, retreat centers, interdenominational ministries, and religious newspapers, magazines, and radio programs. They would remain cloistered in their separate sphere—“strangers in a strange land,” FitzGerald writes—until they came roaring back in the 1970s to help form the Christian Right.

That argument about a cultural retreat and reemergence once dominated the historiography of American fundamentalism but has been out of favor for more than a decade at least, challenged by the works of historians, including Darren Dochuk, Daniel Williams, and Matthew Avery Sutton, who have demonstrated fundamentalists’ ongoing political activism and public engagement through the twentieth century. FitzGerald’s use of this rather outdated depiction of fundamentalists draws one’s attention to her bibliography that leans heavily on older scholarship while missing several path-breaking recent books. The absence of Molly Worthen’s Apostles of Reason, easily one of the most important studies of American evangelicalism of the last decade, is probably the most surprising omission, but there are big gaps from the scholarly literature on topics like gender, race, and capitalism, to name just a few of the richest terrains historians of evangelicalism have explored of late.

Still, FitzGerald captures the tensions, conflicts, and divisions that enlivened and reshaped conservative Protestantism, particularly in the first half of the twentieth century. While separatist fundamentalists continued to splinter from each other over every matter of theology, another set of conservative Christians united across denominational lines under the banner of “neo-evangelicalism.” The neo-evangelicals, led by radio evangelist Charles Fuller and the Boston pastor and theologian Harold Ockenga, espoused fundamentalist beliefs but took a positive stance on engaging the larger world. Carl Henry’s 1947 book The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism, a seminal text for the neo-evangelicals, chided fundamentalists for abandoning the Christian obligation to social reform while attacking Social Gospelers for turning from the historic theology of salvation in favor of promoting social activism. The neo-evangelicals saw themselves as the authentic embodiment of true Christianity, combining the theological orthodoxy of fundamentalism with the social conscience of liberal Protestantism.

The most famous figure of neo-evangelicalism, of course, was Billy Graham, the handsome revivalist who preached to millions of Americans in overflow stadiums and had the ear of every president. Through his ministry and in Christianity Today, the magazine he helped found, Graham more than anyone else helped consolidate the diverse world of conservative white Protestants around the evangelical identity. In FitzGerald’s smart chapter on Graham, one appreciates not only the monumental significance of Graham’s unifying work, but also FitzGerald’s own achievement in sketching out the multiple strands of conservative white Protestantism that Graham would help knit together, including northern and southern denominational divergences, the Southern Baptist Convention, and Pentecostals.

It is worth saying here just how good much of The Evangelicals is. FitzGerald is a deft and beautiful writer, and her book is often page-turning, especially when it covers the different denominational developments and thorny theological disputes that divided conservative Protestants. FitzGerald appreciates how important ideas are to evangelicals, and she skillfully renders complex theological concepts—from dispensational premillennialism to Arminianism to Christian Reconstructionism—in clear and accessible terms. The chapter “The Thinkers of the Christian Right” is a brilliant exposition on how the ideas of R. J. Rushdoony and Francis Schaeffer developed from the intellectual Presbyterian tradition and shaped the rise of the Christian Right. Rushdoony’s hardline views on biblical law as the basis for society attracted fewer devotees, but Schaeffer’s warnings about secular humanism replaced earlier evangelical fears about Communism and “became foundational to the notion of a ‘culture war’ between two totalistic worldviews.”

In the late 1970s, Jerry Falwell seized that message and ran with it, turning from his own personal history of political disengagement. The centralization of Falwell in her narrative of the rise of the Christian Right won’t surprise anyone familiar with that history, but FitzGerald’s astute contribution is to note how Falwell’s political screeds drew from but inverted the logic of Jonathan Edwards’ fiery sermons. As FitzGerald argues, Edwards’ jeremiads inveighed his listeners to repent of their personal sins in order to avoid God’s judgment on society. Falwell reversed that formulation: America’s economic and political decline owed to the moral sickness of the nation, a message that both empowered and absolved conservative Christians “for the sin lay not in the souls of his congregation, but in outside forces.” Christians, therefore, had to step out of their isolation and bring their moral leadership to the nation.

Falwell appears less than halfway through The Evangelicals, and the book slows down considerably as more than 300 pages cover the Christian Right. (A 101-page chapter on George W. Bush and the Christian Right is especially plodding.) FitzGerald keeps alive her theme of evangelicalism’s diversity, but now she depicts it almost solely in political terms. A majority of evangelical leaders spearheaded or at least supported the Christian Right, she argues, while a smaller group, including Jim Wallis of Sojourners and the Orlando megachurch pastor Joel Hunter, became its critics.

As the wide swath of American evangelicalism becomes increasingly flattened into the Christian Right and its opponents, the vibrancy and vitality that marked the first half of The Evangelicals steadily lessens. FitzGerald devotes lengthy sections to events like Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial and the 2008 Republican primaries, but such explorations highlight how much of the lived experience of modern evangelicalism is missing. Aside from Pentecostalism, evangelical worship receives scant attention yet it is significant how much the worship experience has changed for conservative Protestants over the last 50 years. Beginning with the Jesus People in the 1960s and soon spreading through the burgeoning nondenominational churches of the West Coast, contemporary Christian music (CCM) and a relaxed worship style has remade Sunday services for all evangelicals, from Southern Baptists to Anglicans. Mainline Protestants have often tut-tutted the informality of evangelical worship, but the casualization of conservative churches has helped strengthen evangelical identity in part by further underscoring the basic evangelical premise that the Christian faith is not some Sunday morning ritual but an entire way of being.

FitzGerald comments that Joel Hunter grew his Northland Church in Orlando from 200 members to 5,000 in a decade (and more than 10,000 today) “because of its worship services.” (Hunter, it should be noted, is on the national advisory board of the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, which publishes this journal.) His church’s stunning rate of growth is shared by hundreds of evangelical congregations around the country over the last thirty years, but FitzGerald dwells instead on Hunter’s un-conservative politics and his “challenge [of] the Christian right,” as if that is what has made him one of the most important names in contemporary evangelicalism.

At the close of her introduction to The Evangelicals, FitzGerald writes, “the Christian right no longer dominated evangelical discourse” by 2016. It’s a throwaway line, perhaps, but an entirely revealing one. The Christian Right—nor politics in general—has never dominated evangelical discourse. Imagining so betrays an inability (or unwillingness) to fully understand the complex and varied lives of American evangelicals and, importantly, what matters most to them. Even as an author of a recent history of the Christian Right, I would still stress how low nearly all evangelicals rank politics on their list of priorities. Instead, they pray for their children’s salvation and focus on their own spiritual development. They devote themselves to running their churches and participating in community Bible studies. They volunteer with local ministries and send spare dollars to relief work in Africa. They labor each day with the tension of being in this world but not of it. Evangelicals do all of this out of the desire not only to strengthen their personal faith but also with the hope that they might make some difference in their sphere of influence, however small it might be. For evangelicals, that is the real “struggle to shape America,” and it takes place far beyond the rare moments they find themselves in a voting booth in November.

Neil J. Young is the author of We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics. He hosts the history podcast Past Present.