The fraught racial history of the United States has infiltrated and influenced all of its institutions, including the Christian church. Though certain figures and movements did join the struggle against slavery, segregation, and violence at various times and places, the majority of white American Christendom fell somewhere on the spectrum between open endorsement and quiet acceptance. Today, as debates over racism continue to dominate our national conversations and controversies, religious influence remains central to the context.

In his new book, The Color of Compromise, Jemar Tisby surveys this history with an eye toward the innumerable moments when white American Christians could have interceded on behalf of racial justice, but did not. Taken together, he argues, from the founding of the United States to the present, these moments constitute an ignominious timeline spanning four centuries of suffering, so that today’s headlines are connected to seemingly ancient atrocities. By the end, it is clear that past and current events retain a striking similarity regarding the church and race.

Eric C. Miller spoke with Tisby about the book recently by phone. Their conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

R&P: As the subtitle states, your book is a sweeping survey of the American church’s complicity in racism. To your mind, what constitutes complicity?

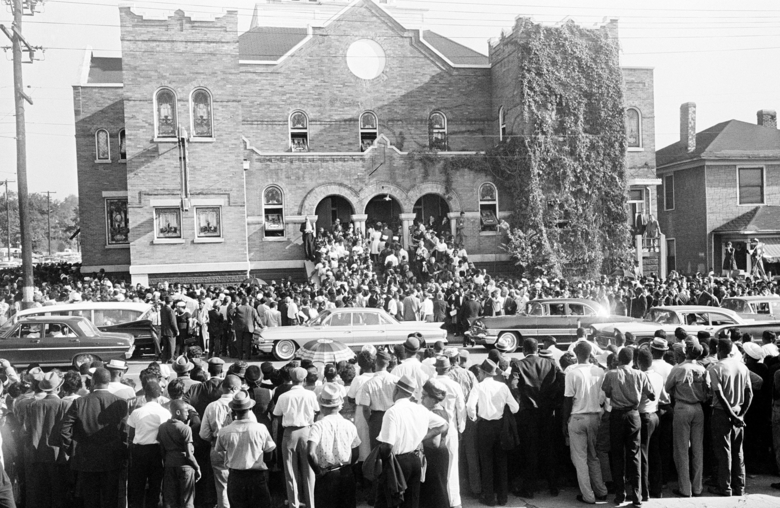

Jemar Tisby: The book opens with the story of four girls who died when the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. Shortly after that event, a white lawyer named Charles Morgan Jr. got up in front of an all-white business club and gave an address in which he asked who was responsible for throwing that bomb. In answer to his own question, he said, “We all did it.”

He went on to explain that every time that the white community—especially Christians—failed to confront racism in its everyday, mundane forms, they created a context of compromise that allowed for an extreme act of racial terror like planting dynamite at a church. That’s the idea of complicity. It’s not that every Christian was a foaming-at-the-mouth racist hurling racial slurs and burning crosses on peoples’ lawns. It’s that when they had the opportunity to intervene in everyday ways, they chose complicity over confrontation, and this enabled a larger atmosphere of racial compromise.

R&P: Though some American Christians were enthusiastically racist and others were anti-racist, most just accepted racist institutions. To what extent are we free to judge that, and to what extent do we have to accept them as products of their time?

JT: I think some would argue that most of those who I am identifying as complicit in racism were merely men and women of their time. But I would respond that the abolitionists and civil rights activists and others who struggled for black freedom were also men and women of their time. So it’s not as though Christians—particularly white Christians—didn’t know there were alternatives. It’s that they must have had some investment in maintaining the status quo, or that they had some fear of what other people would say or what they would risk if they stood up for racial equality.

R&P: Was the situation in the South markedly different from that in the North?

JT: A lot of people like to point a finger at the South and say, “Those are the real racists.” The implication is that there is no comparable problem in the Midwest or the West coast or the Northeast. But the reality is much more complicated than that.

I purposely included a chapter in the book on Christian complicity in the North, and by North I mean anywhere outside of the South. There are examples from various geographic regions. The bottom line is that bigotry knows no boundaries. It’s not that racism stopped at the Mason-Dixon line. The thing that makes the South stand out is that this was the physical site where race-based chattel slavery occurred. It’s the place where the plantations were located. But the entire country was implicated because the agricultural production in the South fueled industrial production in the North and other parts of the United States.

Later, when the country played host to race riots—and here I mean white race riots—these occurred in urban areas outside of the South, like Chicago, St. Louis, Los Angeles, and others in the Northeast as well. So there was no region that was free from complicity and no region that was free from racism.

R&P: As the nation moved from slavery to Jim Crow to redlining and mass incarceration, did the church response reveal any sort of moral trajectory? Did it get noticeably better or worse over time?

JT: Martin Luther King Jr. once said that, when it came to issues of justice, the church was often the taillight rather than the headlight in society. By that, he meant that the church often followed along after changes in the racial status quo were already taking place in different arenas, from politics to entertainment to corporations, and that’s what we often see throughout U.S. history. Though many Christians were actively engaged in struggles for racial equality, they tended to be in the minority. The majority of white Christians, at least, did change, but only as the national sentiment was already moving toward more openness and more equality. The change was slow and a little reluctant.

Consider G.T. Gillespie, for example. In 1954, the year of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, Gillespie was president emeritus of Belhaven College, and he gave an address called “A Christian View on Segregation,” in which he justified racial segregation, he said, based on the Bible. It’s just one example of many white evangelical Christians fighting against the political changes that would promote racial integration.

It was only after Brown v. Board that many Christians capitulated to what was already the law of the land. But there was a disappointing scarcity of Christians who were promoting racial integration or celebrating the end of Jim Crow.

R&P: How did the ascendance of the Christian Right affect the broader church’s positions on race?

JT: If you look at the historical record, it appears that conservative political operatives capitalized on fears and social stances on race that were already present. So it’s not as though politicians had to invent and promote racial fears to white audiences. Those were already there—both overt and covert—within white Christianity.

Rather, the Christian Right marked a coalescence of factors and an intersection of interests, whereby conservative Christians united within a single political party that was becoming nationally ascendant, especially after the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.

R&P: You cite white evangelicals’ support for Donald Trump and their disapproval of Black Lives Matter as instances of modern-day complicity. Have white evangelical readers been receptive to this critique?

JT: Some have been receptive. I think the evidence is in the fact that many more white Christians are talking about issues of justice than in years past.

Ferguson and Black Lives Matter have started a conversation that goes beyond racial integration—and this actually has echoes from the civil rights and Black Power movements a half a century ago—making it apparent, first, that there were deep rifts between black and white Christians, even among those who were worshipping in the same congregations and, second, that our racial chasm could not be bridged simply by knowing people from different races. In other words, the institutional aspects of racism cannot be solved merely through interpersonal relationships. I think there are more and more Christians who are pondering that—and better late than never.

R&P: Early in the book, you predict that many readers will dismiss your argument, and that they will do so via a series of objections that have long been used to defend the status quo. Has that prediction come true?

JT: It has absolutely come true, and I see more clearly now than before, what activists in the 1950s and 60s must have felt when they received criticism from their religious brothers and sisters. The argument is that any talk of social justice is a distraction from what Christians should be focused on, which is the gospel. Throughout history, Christian activists have always asserted that this is an artificial separation—that the two go together. So if you read the comments on some reviews of the book, or on social media posts promoting it, you see some of the same criticisms now that were made in response to activists throughout American history. The main objection to The Color of Compromise has to do with whether Christians should be involved in these topics at all. It reflects, in my view, an over-spiritualizing of the Christian faith that ignores physical, material concerns like poverty, mass incarceration, voting rights, and other important issues.

R&P: You write, “Racism never goes away. It adapts.” That conclusion is certainly supported by the book. But if it’s true, then what gives you hope for a better, more egalitarian future?

JT: The gospel gives me hope. As a believer, I understand that one day, all things will be made right and every tear will be dried. But in a more immediate sense, I have trained my eyes to look for hope in unexpected places. Oftentimes, when we assess the state of race relations in the American church, we look to the big institutions and the big denominations, and the reality is that large organizations are very slow to change. Sometimes they don’t change on a broad scale. So I look for change on the smaller scale, at the congregational level, or a small group of people who have decided to come together and read this book, or to protest in solidarity with immigrants. I look for stories of transformation, in which people who were raised with a certain belief system are now expanding their views to see that racism is still a problem, and that they might play a small role in bringing about justice. Now, these don’t solve the problem by any means, but they show me that there are people who care, and that they care enough to act. And that’s what gives me hope.