This piece is an excerpt from The Spirit of the Game: American Christianity and Big-Time Sports (Oxford University Press, 2024)

Historically, Christians have an ambiguous relationship with sports. From the religion’s earliest days, Christian leaders have expressed concern that sporting spectacles might encourage idolatry instead of true Christian worship. At the same time, the Christian Scriptures also include positive references to sports, with athletic competition used as a metaphor for the Christian life. “Run in such as way as to get the prize,” the Apostle Paul instructs in his first letter to the Corinthians. These tensions have lingered for centuries, with frequent warnings from church leaders about the excesses and corrosive effects of sports juxtaposed with the fact that many ordinary Christians did not seem to listen, instead continuing to participate in sports.

In the nineteenth century, however, in England and the United States, the pendulum began to swing more fully towards sacralization rather than suspicion of sports. Driving this shift was a movement called “muscular Christianity.” Embracing the moral value of sports, muscular Christians argued that athletic competition was an important means of developing well-rounded men, fit in mind, body, and soul to lead the Anglo-American world.

Muscular Christianity helped to popularize the idea that sports had moral value as an essential educational tool—a theory that justified amateur athletics and school sports. Still, suspicions remained over the commercialized spectacle of big-time sporting events, especially since sports leagues competed with churches for attention on Sundays.

After World War II, however, new developments helped ease these tensions. Groups like the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and Athletes in Action forged a network of evangelical sports ministries working within the sports industry. This Christian athlete movement—dubbed “Sportianity” by Sports Illustrated’s Frank DeFord—aimed to unite Christian athletes and coaches around a shared identity.

But even as evangelicals built a new Christian subculture in sports, debates and tensions remained. One key flashpoint had to do with the nature and meaning of the Christian faith. Who would get to determine the boundaries for what counted as a Christian athlete and coach? Who was in and who was out in this evangelical-led movement? Another had to do with the relationship between Christianity and sports. Could Christians still challenge and critique the sports industry even as they worked and thrived within it?

In the 1970s, these questions came to a head for the Christian athlete movement in a prominent way. The debates from that decade continue to resonate today, helping to shape the contours and social and political significance of Christian engagement in American sports.

The trouble began with challenges to longstanding ideas about the moral value of sports. Building on the activism of Black athletes and inspired by opposition to the Vietnam War, in the 1970s a new wave of critics questioned the character-building and democratic potential of athletics. They linked the athletic enterprise instead with authoritarianism, exploitation, and militarization. NFL player Dave Meggyesy’s Out of Their League (1970) was among the most strident of these critiques. “I’ve come to see that football is one of the most dehumanizing experiences a person can face,” wrote Meggyesy, a former St. Louis Cardinal, in a book that also criticized the drug use and racism prevalent in the National Football League. “It is no accident that President Nixon, the most repressive President in American history, is a football freak.”

This sharp condemnation of sports caught the attention of Christian leaders. From the mainline Protestant side, The Christian Century devoted an entire issue to the topic in 1972. “You may think all this is out of place in a serious Christian journal,” the introductory editorial admitted. “Yet it is because sports are so much more than simple amusements that they deserve serious attention.” Articles in the issue generally sided with the new wave of criticism. One author argued that sports had become a new American religion, used by politicians like Richard Nixon to consolidate power. Another suggested that football was built on a foundation of sexism, and that it cultivated tendencies toward “racism, colonialism, imperialism and other types of oppression.”

Christianity Today, the preferred magazine of evangelical intellectuals, did not go as far in its critique, but it attempted to think responsibly about the excesses of athletics with a 1972 editorial that asked, “Sport: Are We Overdoing It?” The article warned that Christians had uncritically embraced the culture of sports, “as if this particular human activity were beyond discussion.”

These censures from Christian intellectuals carried little weight among Christian athletes and coaches. But they could not be ignored entirely within the Christian athlete movement, and debate over how Christians within sports should engage with calls for systemic reform led to three basic responses. Some mostly ignored the debate, instead doubling down on their efforts to save individual souls. “We try to concentrate on Christ and sharing Him,” Athletes in Action director Dave Hannah explained when asked whether his organization sought to address ethical problems. “We’re not committed to change the wrongs, but to change lives which we hope would have an effect on the whole system.”

Within the more ecumenical Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA), this viewpoint was present, too. But there was also support for a second, related perspective. Shaped by the FCA’s establishment impulse, some sought to engage with the debate by actively defending the institution of sports even as they emphasized the need for individual conversion. Since athletics, in this view, were considered a key place for inculcating traditional American values, the potential good far outweighed the bad. Christians were expected to accept the status quo, focus on the positive, and highlight the primacy of the individual rather than the system.

“I’ve come to see that football is one of the most dehumanizing experiences a person can face. It is no accident that President Nixon, the most repressive President in American history, is a football freak.”

The most developed version of this argument came from a book co-authored in 1972 by Bill Glass and William Pinson Jr., a professor of Christian ethics at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. The title made its argument clear: Don’t Blame the Game: An Answer to Super Star Swingers and a Look at What’s Right with Sports. Glass argued that sports were being used as a scapegoat for social problems. Rather than blame sports for brutality, militarism, racism, and drug abuse, Glass argued that those problems existed in sports only to the extent that individual athletes and coaches adopted those mentalities. “It’s the person, not the game, that makes the difference,” he wrote. People in sports needed to stop “blaming the game” and instead accept “personal responsibility” and “get busy setting things right” at an individual level.

Glass recognized flaws in the sports industry, but he also associated athletics with his idea of traditional American values and gradual progress–and he insisted that the way to “get right” in sports was through a personal relationship with Christ. While Glass went deeper than most in engaging with the ideas and perspectives of the new wave of critics, he ultimately affirmed the culture of big-time sports and suggested that any problems could be addressed through individual changes of heart. “People won’t treat others with love and concern until they’ve been changed spiritually by Christ,” he argued

Glass’s perspective resonated with some Christian athletes who did not share his evangelical theological commitments. Dallas Cowboys quarterback Roger Staubach, a Catholic, had little interest in soul-winning evangelism. “I’m just not into the fundamentalist thing,” he would say, separating himself from many Protestant players. But he believed in Glass’s conservative moral views and vision for American society. “Many people will call me a square. If loving my family and being a Christian are the traits, then I’m proud to be a square,” Staubach wrote in the foreword to Don’t Blame the Game. “We aren’t self-righteous prudes, but we do believe in a God-centered morality.”

While Glass’s blend of evangelism with a defense of the sports establishment stood at the center of the Christian athlete movement, there was a third perspective, located on the margins, that showed more sympathy for the concerns of critics. The most prominent advocate for this view was Gary Warner, editor of the FCA’s magazine, The Christian Athlete. A former sportswriter, Warner joined the FCA staff in 1966 after working for Billy Graham’s Decision magazine. He took over as editor of The Christian Athlete in 1968 and began to dream about a new vision for the magazine, one that did not focus only on inspirational testimonials. Working with associate editor Skip Stogsdill, the two announced in 1971 that The Christian Athlete would expand to thirty-two pages and would embrace “healthy controversy” within its pages. “The status quo often needs jarring both within and outside the athletic world,” they wrote. “Material will appear in the CA with which you disagree. If not we haven’t done our job.”

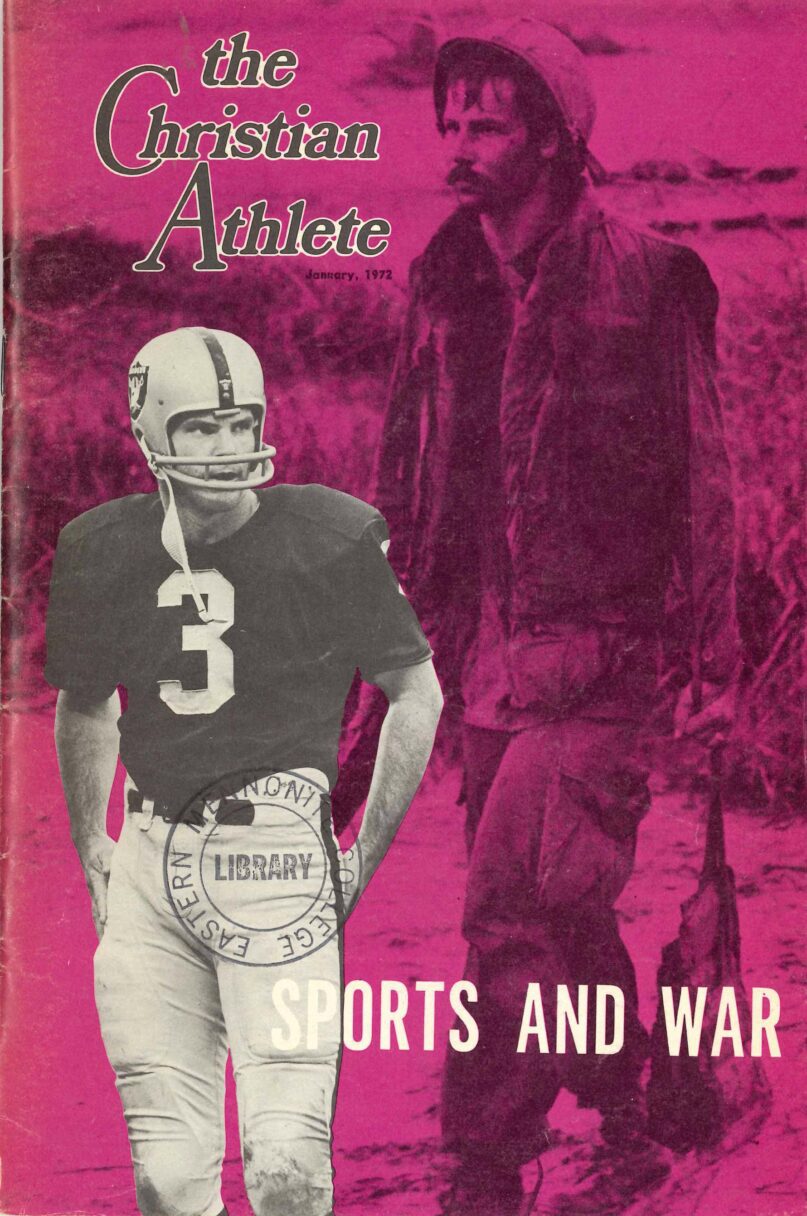

With the January 1972 issue of the Christian Athlete, Warner delivered on this promise. The cover article, written by University of Minnesota student Jerry Pyle, was titled “Sports and War.” Pyle questioned the outsized role that sports played in American life and its connection to a win-at-all-costs ideology that promoted militarism and denied the reality of social injustice. “To make cooperation secondary to victory,” Pyle claimed, “is to worship competition and power and ignore love.” Pyle argued that sports should be reorganized to lessen the emphasis on winning and to promote greater cooperation. A series of photo illustrations juxtaposing scenes from sports with scenes from the Vietnam War added visual weight to Pyle’s arguments.

Warner knew that the article would stir debate, and he penned an editor’s note to distance himself from Pyle’s perspective. He informed readers that he wanted to “editorially tightrope between extremes” of those who were excessively critical of sports and excessively supportive. In short, recognizing that the FCA was the leading organization for the Christian athlete movement, Warner hoped to use the magazine to provide a forum for serious reflection on contemporary issues.

Reader response to “Sports and War” was the largest in the history of the magazine. One letter, typical of the positive responses, praised The Christian Athlete for demonstrating “a new dimension of concern and substance.” Philip Yancey, then serving as editor of Youth for Christ’s Campus Life and later a bestselling Christian author, called the issue “the most courageous piece of Christian journalism I’ve seen.”

Other readers were disturbed. The most strident response came from a Texas golf pro named Bob Goetz. “I am uninterested in a balanced viewpoint,” Goetz declared. “I want dogmatic answers that I can use in a ‘crisis situation’: answers that I can give others seeking positive solutions; answers taught dogmatically in the Scriptures.” In Goetz’s view, The Christian Athlete had fallen prey to liberalism—“a great tool of Satan”—and as such he felt he had no choice but to sever his ties with the FCA.

FCA leaders may not have gone as far as Goetz, but many were frustrated. They wanted The Christian Athlete to focus on the positive and to build up the Christian athletic community through practical guidance and encouragement. They viewed “Sports and War” as a betrayal of the organization’s mission. Bill Glass was particularly upset, firing off a series of angry letters to fellow FCA leaders. In response, the FCA’s board of directors appointed Leonard LeSourd, editor of Guideposts, to serve as chairman of a new publications committee, which would work to limit controversial material in The Christian Athlete. “It is not up to FCA to try and be a judge and jury for all the concerns of the sports or educational world,” FCA president John Erickson later explained. Instead, Erickson saw the FCA’s role as that of “a ‘perspective builder’ and positive organization.”

The furor and fallout over “Sports and War” fit into a larger debate within the evangelical movement over American identity, Christian maturity, and social responsibility. On the one hand, Warner represented the FCA’s evangelical turn. He had experienced a born-again conversion and worked for Billy Graham, and under his watch The Christian Athlete increasingly promoted evangelical authors and ideas. A reader in 1974 recognized this, thanking Warner for centering “the evangelical perspective that I have prayed for and felt the promise of in the FCA since my advent into it some 14 years ago.”

Yet, by the early 1970s, when the “Sports and War” issue was published, a small subset of younger evangelicals was disenchanted with the tendency to associate evangelical theology with conservative politics. Rather than uncritically affirm American institutions, these “progressive” evangelicals echoed mainline Protestant intellectuals by bringing what they regarded as a prophetic voice to such issues as racism, economic inequality, and American imperialism. “You and I have common goals—to exalt Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord,” Warner wrote to Bill Glass in 1973. But that desire played out differently for the two men. While Glass focused on witnessing to the individual person within sports, Warner felt compelled to “speak out against what we sometimes do to sports and to its participants in the name of sport.” In short, Warner shared the progressive evangelical belief that Christian maturity must involve not just a deeper individual piety, but also a growing concern for the social environment and cultural context in which one lived.

Warner’s approach stood outside the methods preferred by most leaders and individuals within the FCA and the broader Christian athlete community. “I like Gary a lot and he is a very capable editor,” LeSourd wrote to Bill Glass, “but like so many young men, in my opinion he gets too wrapped up in the social action issues.” Most FCA leaders wanted practical resources formulated to meet the unique spiritual needs of athletes; challenging the social structures that provided them with salaries and meaningful employment required a level of time and sacrifice that would detract from the ever-increasing demands of big-time sports. Warner may have been an evangelical, but his decision to publish the “Sports and War” issue made it clear: within the Christian athlete movement he was not the right type of evangelical.

In 1977, Warner finally gave up on his efforts to offer a prophetic critique of the sports industry from within evangelical sports ministry spaces. Citing irreconcilable differences with FCA leaders over the direction of The Christian Athlete, he resigned as editor.

His departure did not end debates and discussion over Christian responsibility in sports, but it did help to limit the options. In the years to come, the Chrisitan athlete movement continued to hold a basic conservative orientation on political and social issues. Even more central to its identity was an emphasis on a ministry of presence, on working within sports. No longer was the sports industry an ambivalent cultural space full of potential danger and worthy of suspicion; it was now a home worth defending from the critics.