In the weeks after my father died, I did a lot of fishing. It was one of the few things that afforded a modicum of comfort or distraction. I spent entire days unable to focus on larger tasks, mainly tinkering with my own verses and with English translations of my father’s poetry, until the evening, when I would drive to a kettle pond near our cottage on the elbow of Cape Cod, get into my boat, row out to the middle and drop my line. I was using live bait, and I always ended up with one or two formidable bass and a rainbow trout. I felt that the spirit of my generous and giving father was arranging for the catch to help me cope with grief. I would bring the fish home, clean it, and cook it for supper. Sometimes I ate the fried fish alone, and other times my wife and mother joined me. Our younger daughter is allergic to finfish; our older one doesn’t care for catch “from the lake.”

In the 1970s, when I was coming of age in what used to be the Soviet Union, my father—the writer, doctor, and refusenik activist David Shrayer-Petrov—taught me many skills, from versification to planting potatoes, from taking out splinters to bargaining at a farmers market, from defending my Jewish honor with fists to making Turkish coffee on a gas stove. He also tried to teach me soccer, at which he was superb, but I was foot-tied and useless at the game.

He was successful, however, in teaching me to fish. Together we fished in many waters of oblivion: the Moscow River Canal, mountain streams outside Sochi and in Georgia, rivers and lakes in Estonia and Lithuania. After coming to America in 1987, fishing became our regular father-son immigrant pleasure; we mainly fished in Rhode Island and on Cape Cod. When my father’s Parkinsonian symptoms worsened, fishing was one of the activities he missed the most, and we talked about the miracle of his getting better and reeling in a beautiful bass or trout.

My father—ever the source of book recommendations—had also introduced me to fishing stories. Since reading Sergey Aksakov’s Family Chronicle and especially his Notes on Fishing when I was eleven or twelve, I fell in love with the genre of fish tales, some of them taller than others. As a Soviet Jewish teenager, I devoured a Russian translation of Ernest Hemingway’s short novel The Old Man and The Sea, and so vividly do I remember the rueful homecoming of the old Cuban fisherman Santiago, only a carcass of his gorgeous “ruined” fish tied to his skiff. How could one not love the author of such a glorious fishing tale?

Already after coming to America, I learned to appreciate other English-language literary works about fishing, from Odell Shepard’s Thy Rod and Thy Reel, a confession of divine love for fly fishing, to Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, a classic novella of trout and heartbreak. But Hemingway, himself a passionate fisherman who turned to the topic in a number of works, remained in a league of his own—this in part because my late father so admired his writings and literary mythology. In 1999, my father published a memorial essay about Hemingway, titled “A Writer Who’s Always with You”—a play on A Feast That’s Always with You, the Russian title of Hemingway’s memoir of Paris, A Moveable Feast.

Not only literary fishermen but also literary Jews were at the root of my father’s fascination with Hemingway. Like many other aspiring Jewish authors and intellectuals in the post-Stalin 1950s, my father read Vera Toper’s translation of Hemingway’s first novel, The Sun Also Rises, and fell in love with both the book and its author. As a young myopic Jewish boxer and poet, my father identified with the expatriate American writer Robert Cohn—a fellow fighter and breaker of barriers.

It took me time to confront my father on the subject of Hemingway’s mockery and derision of Jews. We were in Paris together in May 1995, my father had given a talk at Institut Pasteur and was in the brightest of spirits. We spent an afternoon paying homage to the addresses Hemingway mentions in A Moveable Feast. Naturally the walk culminated with picture-taking outside 27 rue de Fleurus, where Gertrude Stein held court and instructed the young, still-unknown Hemingway in the ways of writing and literary politics. I remember telling my father, as we headed toward Jardin de Luxembourg, that at least several pages of Hemingway’s memoir reeked of homophobia and antisemitism (as directed against both Stein and Alice B. Toklas). My father’s answer was: progressivism; anti-fascism; Spain. We left it at that.

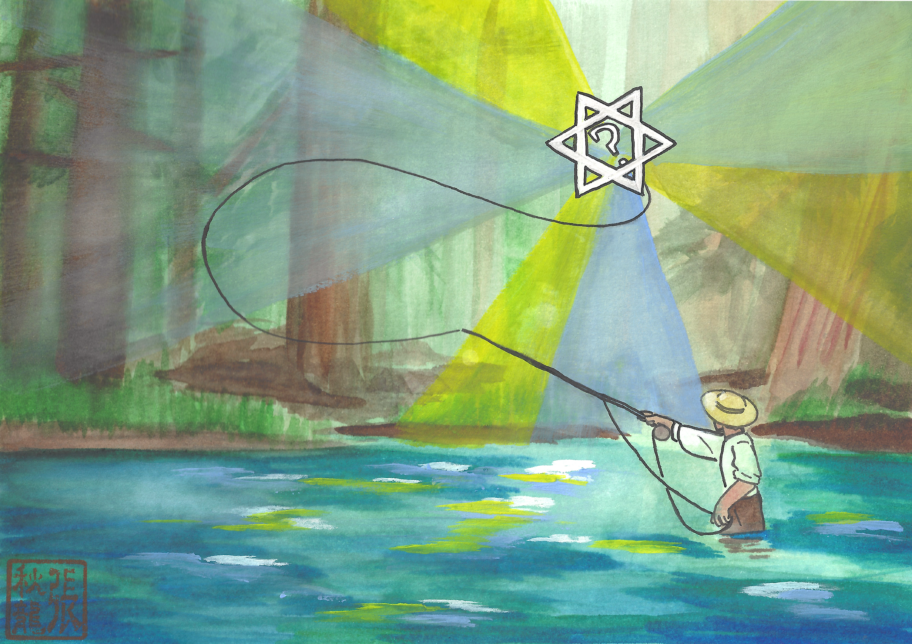

After my father’s death this past June, as I struggled with sorrow, memories of fishing—in life and in literature—sprung to mind. An unextinguished argument about the nature of Hemingway’s prejudice against Jews led me to reread and rethink The Sun Also Rises. In the novel, Hemingway subjects Cohn to antisemitic taunting and baiting, then sends him on a fishing expedition with a group of non-Jewish acquaintances, before finally arranging for Cohn, supposedly an avid fly fisherman, to drop out. Why does Hemingway decide for Cohn to withdraw, I wondered. Is there more depth to Hemingway’s construction of Cohn’s character than what meets the prejudice-expecting eye?

And what about fishing Jews and Jewish views of fishing?

According to Emil B. Hirsch (1851-1923), the Luxembourg-born American Reform rabbi and biblical scholar who held a chair in rabbinical literature at the University of Chicago, “the Bible does not mention any particular fish by name,” while “the biological knowledge of the Talmud concerning fish was of a very primitive order.” Some references to fishing and fishermen are found in the Hebrew Bible, including specific fishing techniques and gear such as nets, hooks, lines, and harpoons. Fishing was an occupation among some ancient Israelites, and traces of that, such as the “Fish Gate” in Jerusalem (Nehemiah 3:3), are found in scripture. Some allegorical or metaphorical references to fish and fishermen also appear in the Hebrew Bible, specifically in prophetic writings. In Jeremiah 16: 15-16, the Lord speaks of gathering the Israelites:

For I will bring them back to their land, which I gave to their fathers:

Lo I am sending for many fishermen declares the Lord—

And they shall haul them out;

And after I will send for many hunters,

And they shall hunt them

Out of every mountain and out of every hill

And out of the clefts of the rocks.

Such fishing tropes later gained prominence in the New Testament, in the episodes depicting the beginning of Jesus’ mission and ministry among the Jewish fishermen on the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret). Famously in Mark 1: 16-18:

Now as he walked by the sea of Galilee, he saw Simon and Andrew his brother casting a net into the sea: for they were fishers.

And Jesus said unto them, Come ye after me, and I will make you to become fishers of men.

And straightway they forsook their nets, and followed him.

Biblical archeologists, notably Mendel Nun, author of The Sea of Galilee and Its Fishermen in the New Testament (1989), warn against the danger of reading Gospel narratives related to Jesus and the fishing communities on Lake Kinneret as accurate accounts of fishing. “I am continually surprised,” Nun wrote, “at how accurately the New Testament writers reflect natural phenomena on the lake. But we should not expect to find clear professional accounts of early fishing experiences in Biblical parables and vignettes….”

A cursory glance at the history of Jewish civilization in diaspora prompts a view that fishing did not constitute a core Jewish occupation or trade, even in the areas of Eastern and Central Europe with the largest pre-Shoah traditional Jewish communities. This is particularly remarkable given the relative ease with which most types of fish could satisfy Jewish dietary laws (kashrut) and the prominence of fish in both Sephardic and Ashkenazi cuisine (think of gefilte fish, usually made of carp, pike, and whitefish). A notable exception is the presence of Jewish professional fishermen in the coastal Jewish communities of the Levant and parts of the Black Sea, be it Thessalonikian Jewish fisherman of the Ottoman and post-Ottoman period or Odessan Jewish fishermen in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This does not mean that individual Jews did not procure fish in the waters adjacent to their communities, but it does beg the bigger question of halachic (Jewish law) positions on fishing, both as a procurement of food and, subsequently, as a sport and pastime.

The halachic skepticism toward the activity of hunting for animals in the wild, based to a significant degree on the more general prohibitions against cruelty to animals (tzaar baalei chaim) and against wastefulness (bal tashchis), applies to fishing, although perhaps in a more nuanced fashion than it does to hunting. In 2015 Rabbi Yehoshua Pfeffer, Head of the Haredi Israel Division of the Tikvah Fund, addressed the subject with a comprehensive historic perspective. According to Pfeffer, “The question of hunting for sport in Halacha was first raised in the seventeenth century, and its main occurrence in responsa literature is in the eighteenth century, when the social status of Jews in some parts of Europe rose and some became landowners. Halachic authorities generally prohibited hunting, for a variety of reasons.” Pfeffer continues: “Thus, one may kill animals to make a living, but not to be cruel or to kill animals purely for entertainment. Hunting for pleasure is a form of cruelty, and destroys a person’s inner qualities and traits.” He then asks a key question that bears on my own inquiry of fishing as a sport and a pastime: “Is fishing similar to hunting? Our intuition tells us that it isn’t—hunting is a cruel and bloodthirsty sport, whereas fishing is a quiet and soothing pastime. Might it be forbidden?”

Jewish religious commentators have considered the question of fishing with means that inevitably inflict pain on the fish, such as hooks or harpoons. Pfeffer offers a modern answer to this ancient problem: “Where the fishing trip is required for therapeutic or medical reasons, it is of course permitted—though it remains better to keep the fish for consumption, where this is possible.” In summary, a traditional Jewish religious sensibility tolerates commercial fishing and fishing to procure food but holds negative or skeptical views of fishing as leisure or sport.

The very idea of Jews who fish not for consumption and sustenance but as a recreational activity—a gentlemanly sport—gains some relevance in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with the rise of the acculturated Jewish bourgeoisie in Europe and the United States of America. In the second half of the twentieth century, the question acquires even greater significance as Jews increasingly live in the mainstream of Western societies. There is thus a bifurcating view of fishing as both a gentlemanly sport and as ordinary people’s procurement of food—a dichotomy that points to Hemingway’s Cohn and his sudden—and portentous—misgivings about fishing.

I fell in love with the genre of fish tales, some of them taller than others.

When Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (British title Fiesta) was published by Scribner’s in October 1926, American literature was not exactly peppered with Jewish names. At the rotting heart of The Sun Also Rises lies Hemingway’s struggle with his own antisemitic petty demons. Hemingway was not the only left-leaning American author—and not the only literary light of the “Lost Generation”—to give voice and form to a sordid ambivalence about the place of Jews in the cultural mainstream. At least in his public persona of the 1920s and 1930s, Hemingway abhorred racial antisemitism and understood full Jewish equality as a basic tenet of progressivism. Yet as a writer, Hemingway was not only prone to reproduce Judeophobic canards of the most basic sort, but also to voice a hostility toward deeply acculturated Jews who were writers and artists.

This brings us back to Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises, who had his prototype in the Jewish-American writer Harold Loeb (1891-1974). Descendant of a German-Jewish family, son of an investment banker, and a cousin of Peggy Guggenhgeim, Loeb founded the international magazine Broom and is probably best remembered by the title of his 1927 novel, The Professors Like Vodka. Loeb and Hemingway were friendly when they both lived in Paris in the 1920s, and Hemingway repaid Loeb’s generosity by giving him a novelized, tragic-comic part in The Sun Also Rises. Referring to the fictional evisceration of Loeb in The Sun Also Rises, Mary Dearborn, a Hemingway biographer, said that “Hemingway could not forgive anyone who did him a good turn.”

Jake Barnes, Hemingway’s narrator in The Sun Also Rises, is a Paris-based American journalist whom a World War I injury had rendered sexually impaired. Barnes introduces his acquintance Robert Cohn, who comes from a wealthy New York family, as a former middleweight champion of Princeton. American Jews had excelled at boxing before they did in other athletic activities, because boxing focused on individual performance and was one of the least clubby and elitist of the sports. Jake claims that “[n]o one had ever made [Cohn] feel he was a Jew, and hence any different from anybody else, until he went to Princeton.” Jake Barnes speaks of Cohn’s boxing as a vehicle to “counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he had felt on being treated as a Jew at Princeton,” and also of Cohn’s inner “distaste for boxing”—and, as the novel reveals, for other spectacles of violence, notably for bullfighting. And yet, as the novel’s ending shows, the mild-mannered Cohn has not lost the ability to fight.

The writer Dan Grossman, who has written with sympathy and wit about Loeb and his fictional alter ego Cohn, characterized Cohn as “a clumsy romantic, a Jewish Quixote with his head in the clouds and his feet in a WASP’s nest.” And yet Hemingway made Cohn both more stereotypical and more ponderous as a Jew on the Left Bank of expatriate Americans. The distinguished critic George Monteiro argued that Hemingway complicated Loeb’s Jewish background by giving Cohn a German-Jewish father and a Sephardic mother (who allegedly came from the original Jewish families that had fled from Brazil in 1654). In that sense, the trip from Paris to Spain, during which the novel implodes with visceral Jew-hatred, was also a symbolic return to the Iberian roots of Cohn’s Sephardic ancestors. Did Monteiro give Hemingway’s historical imagination a little too much credit as he negotiated ways of thinking apologetically about Cohn’s portrayal?

At the rotting heart of The Sun Also Rises lies Hemingway’s struggle with his own antisemitic petty demons.

In the novel’s various registers of malevolence toward Cohn—wrapped inside the overarching authorial voice and spoken by Hemingway’s representative Jake Barnes—one hears residues of Christian Judeophobia entwined with American upper-middle-class dread of associating closely with “the Hebrews”; there is also a Henry Ford–style fear of an international Jewish takeover of the world. Such presentation of Jews is particularly odd for a literary work by someone who, in his young Parisian years, got to know many assimilated Jewish artists and writers from many parts of Europe, including France, Italy, Poland, and the former Russian Empire, and later encountered many Jews fighting on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War.

Still in love with Lady Brett Ashley, the novel’s femme fatale, Jake Barnes is morbidly jealous of Cohn, with whom she has a fleeting affair, and resents him for it—as does Brett’s fiancé Mike Campbell. Jake, Mike, and Jake’s pal, the writer Bill Gorton, jointly showcase a spectrum of antisemitic behaviors, from the more sophisticated varieties of the genteel American fashion to the openly crude and visceral. For instance, Jake opines that Cohn “had a hard, Jewish, stubborn streak,” whereas Bill says, of Cohn, “Well, let him not get superior and Jewish” and refers to him as a “kike.” Mike, incensed, insults Cohn by suggesting he does not belong in their company: “I’m not clever. But I do know when I’m not wanted. Why don’t you see when you’re not wanted, Cohn? Go away. Go away, for God’s sake. Take that sad Jewish face away. Don’t you think I’m right?”

At the root of this antisemitic taunting of Cohn lies white America’s fear that Black and Jewish men would possess white women. Already present in the nineteenth century, this paradigm of intolerance would subsequently feed into the creation of Nazi propaganda and legislation against the “racial defilement” of Aryan women. Culturally speaking—and two of Cohn’s principal detractors are writers—this prejudice is a watered down version of the Wagnerian angst that Jews are penetrating and polluting “pure” Christian and Aryan culture.

The Sun Also Rises culminates with a trout fishing expedition to Burguete, a town in the hills of Navarre close to the Spanish-French border, and a discordant fiesta in Pamplona. Cohn plans on fly-fishing for trout in the Irati river, but in the end, he stays behind in Pamplona, while Jake and Bill have a glorious fishing expedition. An explanation in synch with the logic of the novel’s triangle of desire would be that Cohn falls behind to await Brett and her fiancé, still unable to tear himself away from her. An alternative explanation, and the one I now favor, is that it dawns on Cohn that the image of a Jew fly-fishing with antisemitic bigots is both absurd and incongruous.

Hemingway’s artistic design trumps the author’s own outbursts of intolerance. An explanation that takes seriously what Hemingway’s novel knows without verbalizing it would be that Cohn—an acculturated, upper-class American Jew—has unresolved, residual ambivalence about fishing in general, and especially fly-fishing. Trebly shunned by the Gentiles—as a Jew, as an artist, and as an angler—Cohn bows out of the trip. He is not only emotionally and intellectually reacting to the taunts by his companions but also Judaically rejecting this gentlemanly sport and pastime. Seeing a few more silver linings in Hemingway’s artistic construction of his Jewish character also allows us to recognize a greater Jewish virtue in Cohn himself—all achieved to catch and to catch not.

In our old Moscow apartment, portraits of several authors adorned my father’s den. There was a drawing of young Boris Pasternak, a Russian Jew who looked a lot like his Sephardic ancestors, and photographs of a forlorn silver-bearded Ernest Hemingway clad in a fisherman’s sweater, and a half-smiling Robert Frost sporting a herringbone coat and wool scarf. My father saw Frost recite his poems live in Leningrad in 1962, the year my parents were married, and to the end of his life he remembered the “towering stranger” who, for my father, betokened the openness and expansiveness of American culture rather than narrowness or xenophobia. It was more complicated with the legacy of Pasternak and Hemingway. Both Pasternak and Hemingway were my father’s youthful loves, and in the weeks following my father’s passing I’ve come to see that he never unloved them, even during his refusenik years of being ostracized—and despite his growing understanding of both Pasternak’s Jewish religious apostasy and Hemingway’s anti-Jewish prejudice.

As I reel in a catch or wrestle with a literary conundrum, I remain my father’s disciple. I refuse to catch and release. For me, fishing without my father and rereading Hemingway are ways of learning to dwell in a world where my father is not physically by my side but is still vibrantly alive. I can only hope that he would like this interpretation of one of his favorite novels. I know my father is glad when a rainbow trout lies in my open palms—like a book of love and memory.