The biggest surprise of my November 2024—and remember, that’s a pretty high bar—was that I didn’t totally hate Wicked. Beyond the franchise-driven drek lie a good story, truly great performances, and brisk pacing that makes the film’s two hours-and-forty-minute run time sail by.

And yet, as much as I enjoyed the movie, I was sad about what was missing: religion, politics, nuance, mysticism, science, class, and God.

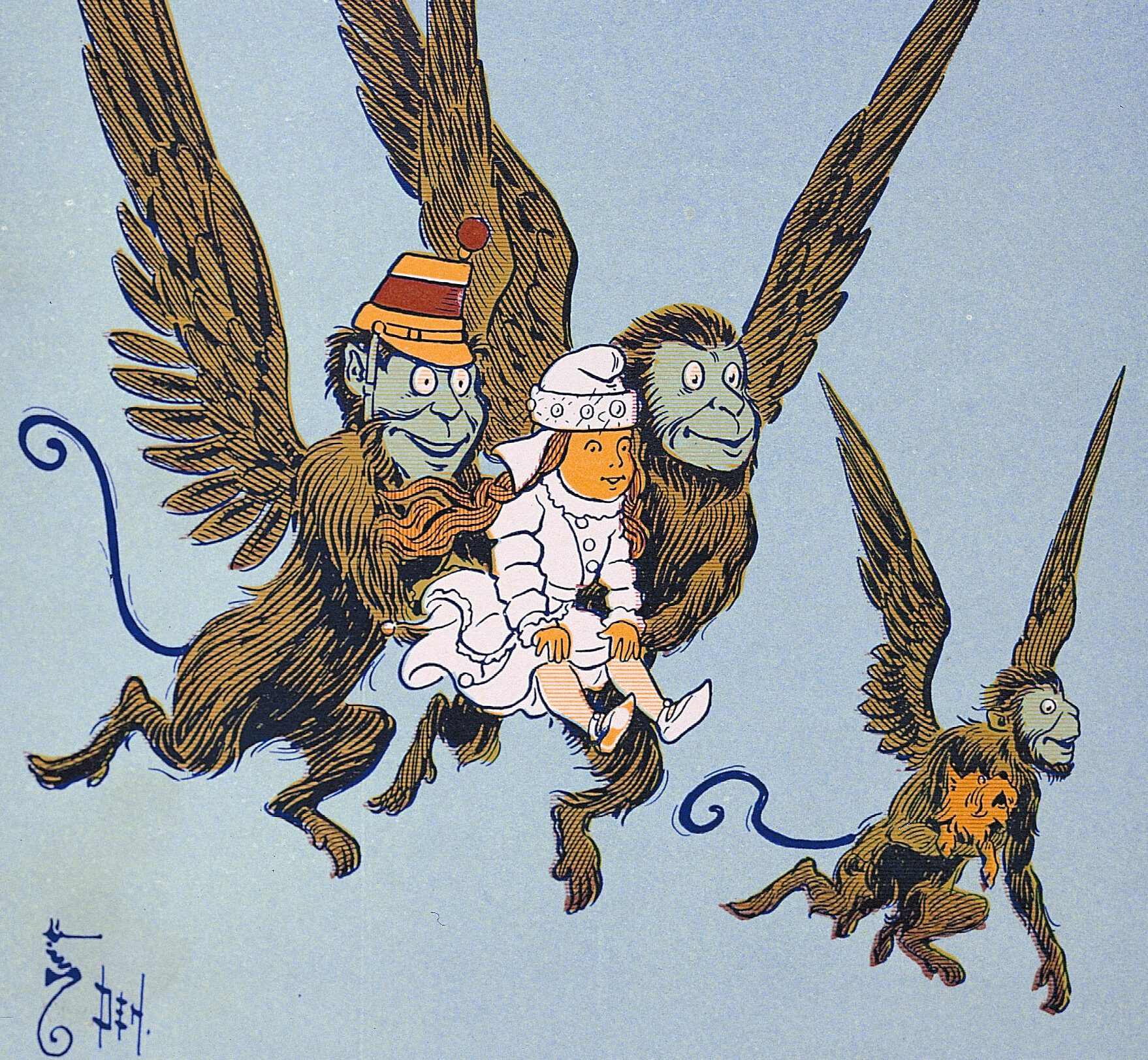

The Oz books—fourteen in total, written by L. Frank Baum from 1900 to 1920—began with a map showing the land quadrants of Oz: Gillikan, Winkie, Quadling, and Munchkin. It was a story about feudalism and territorial battles, about caste and bias and exploitation. It was also about magic, the real kind, the kind we all possess, and the false fixes that politicians promise. In 1900, as railroad barons were laying track to monetize the American West, and farmers were being duped into stripping arid fields and creating the Dust Bowl, Baum imagined an alternate reality—futuristic, full of robots, unprecedented species, and wild sorcery. Oz was a little like our world but preferable, crazy with danger and opportunity. A place where one earthly colonizer could plummet in and set everything right.

In 1995, Gregory Maguire published Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, a book that kept the magic of Baum’s stories but turned it ten shades darker, revealing layers of sex, deceit, power, and evil that the children’s books had only hinted at. In this version, Dorothy wasn’t the heroine; she was the dumb, entitled intruder who let herself be the instrument of a destructive and authoritarian regime. And Elphaba, the Wicked Witch, was a clever but misunderstood and embittered crusader for good.

I read Wicked shortly after it came out—because I followed everything Oz—and loved it. The reviews were mostly superb. John Updike, writing for The New Yorker, called it an “amazing novel.” But it was a sleepy, niche book until Winnie Holzman rewrote it for stage in the early aughts.

As much as I enjoyed the movie, I was sad about what was missing: religion, politics, nuance, mysticism, science, class, and God.

Today, Maguire’s work is sometimes referred to as “fan fiction,” which I think diminishes it. Wicked the novel was more adaptation, a standalone prequel to The Wizard of Oz, as Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea was to Jane Eyre.

And here we get to my complaint about the film, as well as the insipid Broadway musical it was based on: so much of what made Wicked the novel great was its utter darkness and complexity, its reflection of our culture and confusion, the barbarity of this era in history just like every other one. It is as predictive as Nineteen Eighty-Four and as metaphorical as Frankenstein. In the stage and movie version, 95 percent of that is stripped out.

Maguire turned Baum’s four territories into four religions: Unionism, Lurlinism, Tiktokism (from the character Tiktok in the original series), and the Pleasure Faith. But instead of straightforward theology, he infused politics and land rights into the faith-based wars (sound familiar?). Unionism preached a mashup of communism and an Unnamed God; Lurlinism was fundamental deference to a fairy queen deity; Tiktokism involved worship of technology and The Clock of the Time Dragon; and the Pleasure Faith was exactly that—hedonism and sorcery inspired by a Kumbric witch.

In Wicked the novel, one of the central tensions is around the rights of Animals (capital “A”), meaning creatures with a soul; and animals (small “a”) who have no higher-order spirit and can be used as workers, caged, or eaten. When the dumb and despotic Wizard seeks to increase his hold over the proletariat (Munchkin farmers, Quadling laborers, Winkie tradesmen), he puts the Animals in chains and offers them as a lower-class target for the people to exploit.

Maguire’s book also explores the role of propaganda and secret (or, as one might say today, “deep state”) forces within a totalitarian regime. Magical spells double as mantras that “charm” a gullible populace into hating the outsider. Elphaba is driven underground for her wrongthink—in the parlance of today, canceled. When her sister is killed by a falling house, the silver shoes that are her birthright are seized and gifted to the murderer, all in the name of fairness.

The Oz of Maguire’s Wicked is a place where caste matters and the appearance of Glindaesque goodness is used as a shield. Strains of racism, antisemitism, Islamaphobia, and anti-gay discrimination run throughout the book. Its stock religious characters are concerned with moral purity, as each sect defines it. Wicked opens with the Tin Man—a working class hero in Baum’s original—saying about the Witch of the West, “She was castrated at birth. She was born hermaphroditic, or maybe entirely male.” The scarecrow chimes in, witheringly, “She’s a woman who prefers the company of other women.” This othering is a moral shortcut, a lazy, preachy way to paint Elphaba as evil without engaging in facts. The truth: she is flawed, nettlesome, and short-tempered, but she is a profoundly wise and ethical heroine.

In the novel, Elphaba is far from perfect. She’s prickly and occasionally unkind, especially to Boq, a Munchkin who is her stalwart friend. Born to a stone-souled minister and a drunken, straying lady of good lineage, she grows up on the outside. Her skin is green; no one knows who her real father is. She is sexy and wild. Her magical gifts are great but unruly, and reviled by the man who raises her. She is not the resilient, dancing, beautiful “good girl” you see on screen.

The novel is as predictive as Nineteen Eighty-Four and as metaphorical as Frankenstein. In the stage and movie version, 95 percent of that is stripped out.

What’s missing most, in the translation of novel to musical and then screen, is the examination of science and its role in the way societal power is accrued. In the novel, when Dr. Dillamond’s research shows that there are cellular differences between Animals and animals, he is killed by a furtive agent of the state and replaced by a professor who delivers government-approved messages, quashing magic.

“Science is the systematic dissection of nature,” Maguire writes, “reduc[ing] it to working parts that more or less obey universal laws. Sorcery moves in the opposite direction. It doesn’t rend, it repairs. It is synthesis rather than analysis. It builds something anew rather than revealing the old.”

The sloppy overlap of government control in what is considered acceptable science, the denial of facts that do not fit the sacred text of the elite, the condemnation of anyone who brings countervailing evidence to light? These dilemmas that played out in our own world this very decade are all in the book, but nowhere to be found in the adaptions for stage and screen.

Wicked the film—by necessity, I’m sure—reduces so many of these intricate elements to their more hollow contemporary analogues. The father is a garden-variety “toxic, narcissistic” father, who rejects Elphaba because of her skin color and favors her sister, the beautiful wheelchair-bound girl (who, in the book, was armless and puritanical). Prince Fiyero is a brash, handsome bad boy, rather than a dethroned and terrified Winkie. The class differences between Animals and animals; the research into genetic superiority; the dangers of government deciding issues related to faith and science; and the bawdy, transhuman trashiness of the Time Dragon Clock—all missing.

What’s left is a pleasant and cohesive story that follows a direct and unsurprising plot, reminiscent of the 1971 film Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory but without the dryness or wacky turns of Gene Wilder. Instead, Wicked is pure kitsch and sparkle, a movie with stunningly beautiful people—even the ones held up as supposedly monstrous—who all get along and try try try to do the right thing.

In other words, it’s a musical for an audience that, I’m aghast to discover, wants to sing along. It’s a sweet film with a good message that will satisfy adults and children alike. So much so that even I could let go of my tenacious loyalty to the books for two-plus hours, lie back in my seat, and enjoy.