Most Americans, if they know Opus Dei at all, know it as a fictionalized cabal in The Da Vinci Code. But the Catholic order is real, has branches all over the world, and, according to journalist Gareth Gore, has a deep history of unethical and illegal behavior, including fraud and human trafficking. In his recent book, Opus: The Cult of Dark Money, Human Trafficking, and Right-Wing Conspiracy Inside the Catholic Church (Simon & Schuster, 2024), he traces the organization’s history back to prewar Spain, discusses its connections with the Franco dictatorship, and looks at its deep, often secretive influence on Spanish society and elsewhere. My interview with him has been condensed and edited, without—I hope—losing any of its spice or flavor.

Mark Oppenheimer: How did you come upon this story that turned into this book?

Gareth Gore: Over the past ten years or so, I’ve covered a lot of bank collapses. And in 2017, I was sent to report on this Spanish bank called Banco Popular. At first, it seemed it had just kind of fallen into the same trouble as everyone else—its managers had taken too many risks, allowed things to get out of control. I came into that story through the prism of, “Oh, it’s going to be the same old story of unbridled ambition and risks spiraling out of control.” And that’s the story I wrote initially.

But then by sheer chance two years later, I was back in Spain. And I decided to look at that bank collapse again. I made contact with a lot of the protagonists, and I discovered this amazing untold story, which was basically that Opus Dei had hijacked this bank in the 1950s and had used this bank as a cash machine for close to sixty years. And I got dragged into this rabbit hole of archives and years of interviews.

MO: What had you thought Opus Dei was?

GG: I knew very little about Opus Dei coming into this. My partner is Spanish, and her brother had gone to an Opus Dei university. He wasn’t connected to Opus Dei in any way and still isn’t. But I knew it mainly as a kind of Spanish phenomenon, this quite conservative organization that had tentacles running into all parts of Spanish society but which—at least this was my impression—had very little clout outside of Spain.

I started to do my homework. I read voraciously, anything that I could get my hands on. And I spoke to as many current and former members as I possibly could to piece together what the organization was. I got in touch with a former member who had spent many years inside the organization and who had smuggled out all of these internal documents. And that opened my eyes to what Opus Dei really is.

To the public, Opus Dei presents a veneer. It pretends that it is simply a religious organization that wants to help Catholics live out their faith more deeply. The philosophy of Opus Dei is supposed to be that by striving for perfection in whatever you do, whether you’re a teacher or a journalist or a doctor or lawyer, by striving for perfection, that’s your way of serving God. There’s no need to become a priest or a nun to serve God. You can do it just in your normal life. That’s the sugarcoated philosophy that they spoon feed the public.

But thanks to speaking to people who’d lived inside the organization, and thanks in particular to these secret documents that were smuggled out of the organization, I now understand Opus Dei to be something completely different. Opus Dei for me is a deeply political, a deeply reactionary, organization that aims to infiltrate society at the very highest levels. Infiltrating governments, the judiciary, the upper echelons of the business world. And using its influence in those parts of society to push its reactionary agenda, to turn back the clock on the sexual revolution, contraception, affirmative action.

MO: Let’s talk a little about the founder. Who was he and what did he believe?

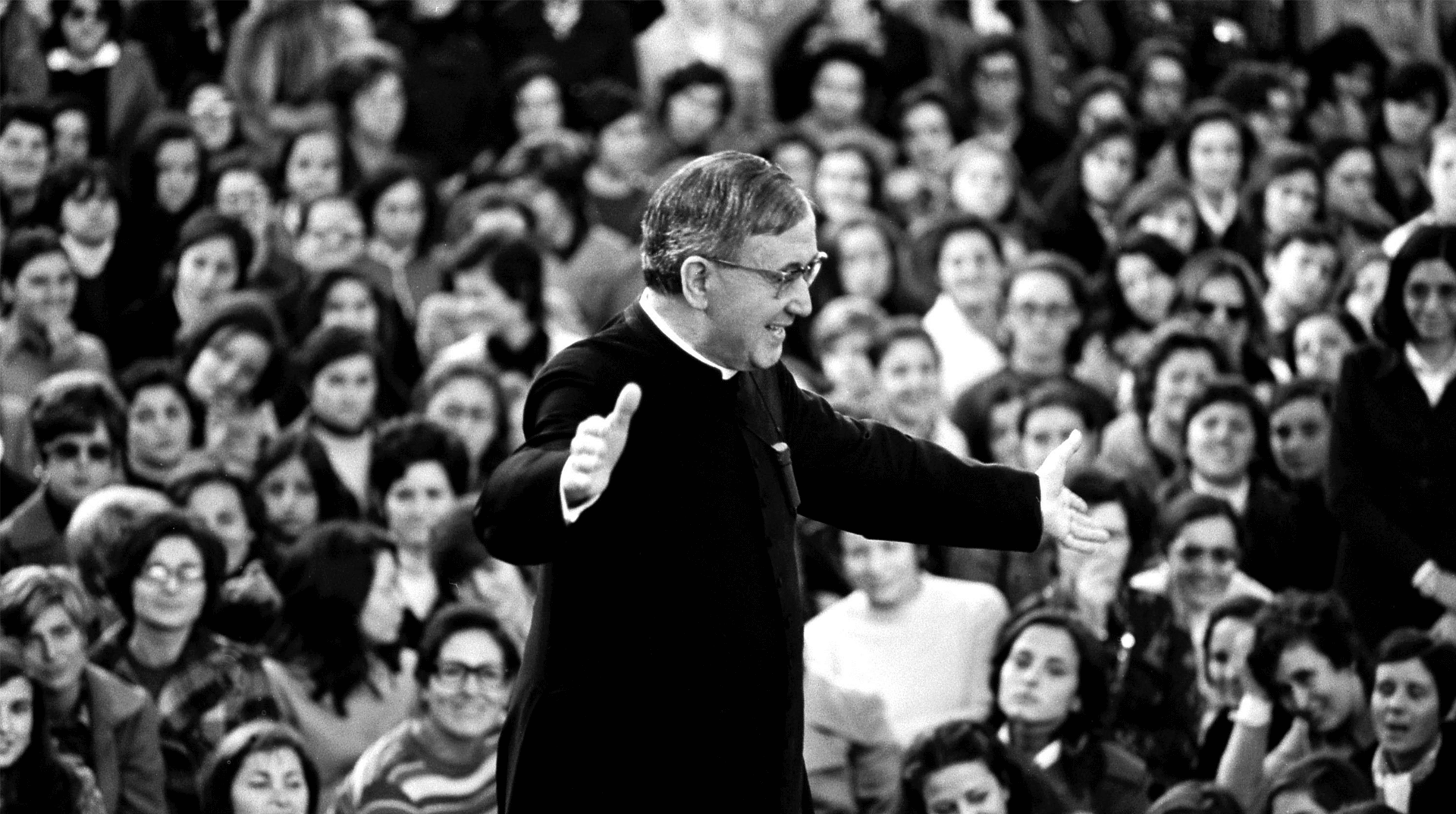

GG: The organization was founded by a Spanish Catholic priest, Josemaria Escrivá, in the 1930s in pre-civil war Spain, when society was deeply divided. He was born in northern Spain in 1902. The best way of getting a really good education in those days was by joining the church, joining the seminary. That really opened up your options. So he went to the seminary and he became a priest, but his passion really was law. For a long time he considered just leaving the priesthood entirely. He applied for various jobs.

But then one day, while he was on retreat, he had what he called a vision from God. He said that God had effectively spoken to him and given him the outlines of this new organization. He’d received this vision from God of how ordinary Catholics could better serve God in their ordinary lives.

For many years, he was really quite unsuccessful at recruiting anyone into the movement. Three, four, five years after initially getting this vision, he could count on one hand the number of members in Opus Dei. It was rapidly becoming something of a failure. But then interesting things began to happen. In the early 1930s, Spain was on the brink of civil war. The country is deeply divided. The workers have risen up against the monarchy. They’re demanding new rights for themselves. And—critically for this story—they’re beginning to turn their backs on the church.

And Escrivá, as a priest, as a conservative man, he’s appalled by this. He starts believing all of these conspiracy theories. He blames it on the communists, on the Bolsheviks, on the Jews and the Masons. And this organization that he’d founded just a few years earlier, on this quite benign philosophy of serving God through striving for perfection in your daily lives, begins to take on this sinister and deeply political hue.

He rewrites the foundational documents—documents which are kept secret for the next hundred years. They are still secret today, and we only know about them thanks to people who smuggled them out of the organization.

MO: So wait, just to be clear, are you the one who revealed these documents for the first time?

GG: This is the first time they’ve been published, certainly in a book. Some of these documents have popped up on the internet over the years, but they’ve been quickly taken down because Opus Dei is very litigious, and as soon as these documents have popped up on the internet, the organization has gone after whoever’s posted them and threatened to bankrupt them, basically. It’s kind of funny, because the legal threats themselves confirm these documents are real. The laws that they’ve used to force people to take them down are copyright-infringement laws, so basically by using these laws, they’re confirming, “We own the copyright to these documents.”

So we now know in these documents that Escrivá outlined in secret a new mission for Opus Dei, which was to infiltrate every element of society and use Opus Dei’s power and influence there to shape society according to what he called the “orders of Christ.” And of course the orders of Christ would be channeled through Escrivá himself, and passed down to his troops.

MO: Can you say a bit more about what these documents are? First of all, how long are they? Are we talking five pages or five hundred?

GG: There are hundreds of pages of documents.

Opus Dei is at its core a cult organization where there are certain tiers of membership. The vast majority of members are what they call supernumeraries. These are people that just live out in the world. They have families, they have normal jobs. But there’s this inner core called the numeraries. And these are people who live celibate lives, they live in gender-segregated residences where every movement is controlled. They’re basically watched and manipulated the entire time, these numerary members. He wrote hundreds of pages of documents detailing how these numerary members were to be controlled, how their lives were to be led, how the numeraries were then to interact with the supernumeraries in order to kind of push forward this agenda.

The instructions that he wrote—and he called them “instructions,” actually—the instructions that he wrote dictate even the smallest aspects of the numeraries’ lives, from detailing how any correspondence that they sent to the outside world, or any correspondence that they might have received from their families and friends, was to be opened first and checked. And detailing how they spent almost every minute of their lives. It’s real cult-like behavior.

MO: I’m having trouble getting a handle on what exactly these people all do. You have the numeraries, who are mostly not priests, but they’re celibate and they live in houses segregated by sex , and they recruit supernumeraries, who—what? Give money to Opus Dei? Like, what’s the work? What’s the stuff that they’re striving for here?

GG: Yeah, so you’re right. The most critical mission given to the numeraries is to recruit. They’re to recruit, as you say, the supernumeraries, because those are the people that are out in society, the people that will be giving big donations back to Opus Dei, the people who are in positions to influence society. But they’re also charged with recruiting the next generation of numerary members as well, the next generation of celibate members, this kind of elite core of Opus Dei.

And that’s particularly pernicious, because potential numeraries are targeted when they’re children, through the Opus Dei school network, Opus Dei youth clubs. And connections with Catholic families are used to single out and target and groom children from a very young age—eleven, twelve, thirteen years old—and to slowly kind of indoctrinate them and convince them that they have a vocation to become a numerary member of Opus Dei.

But among the people that have already been recruited, the numeraries are also given this additional task: they are tasked with giving what’s called “spiritual guidance” to the Opus Dei membership, to the supernumeraries and to other numeraries. And spiritual guidance covers everything. So, of course, as devout Catholics, they go to confession regularly, they confess their sins. But as members of Opus Dei, they’re also expected to do these weekly or biweekly “chats”—that’s what they call them. It’s a way for the numerary to teach you how to be a better Catholic. But it covers everything. As an Opus Dei member you’re expected to offer up your innermost thoughts: about your professional life, your personal life, your sex life. You’re expected to offer up information about your friend network.

And this information is collected by the numerary, who’s meant to be giving you spiritual direction. And then, at least in the past, it was passed up the chain through the Opus Dei network, and at the national headquarters they keep files on the members, and work out how to better use this network to push forward their aims.

I got in touch with a former member who had spent many years inside the organization and who had smuggled out all of these internal documents. And that opened my eyes to what Opus Dei really is.

MO: And the network includes, they hope, influential people: jurists, politicians, and so forth. Who, because of their membership in Opus Dei, are aligned with the reactionary teachings of Escrivá and can push them forward in government and policy. Is that the idea?

GG: Yes. And it’s not that they hope that they’ll attract these kinds of people—they specifically go after these kinds of people. I mean, one kind of interesting data point here: the largest Opus Dei community in the United States is in and around Washington, D.C. And that tells you all you need to know about how Opus Dei has focused its recruitment operation over the years. Another big recruitment ground for Opus Dei is universities, and in particular, in the U.S., Ivy League universities.

MO: Let’s go back to Esrivá in the 1930s and ’40s and ’50s. One of the common understandings of Opus Dei is that it was an adjunct to the Franco dictatorship. Is that true?

GG: Oh, absolutely. There is no doubt about it. So before the Spanish civil war, before Franco’s victory, Opus Dei was failing. After almost a decade of trying to recruit people, Escrivá had only managed to recruit about twenty members. But the war and Franco’s victory completely transformed the organization’s ability to recruit. Franco decided to make religious studies compulsory at all universities, and he actually encouraged religious orders to set up halls of residences across Spain. His thinking was that by effectively forcing students to live in these halls of residence that were run by religious orders, it was a way of keeping tabs on the student population. And Opus Dei really stepped up to the plate. It took advantage of these requirements to set up dozens of student residences all across Spain. And that’s when its membership really started to take off.

Two things came together. One was this requirement for students to live in these halls that were run by religious orders. And the other thing was that over the years, Escrivá had developed these methods of recruitment that were really quite effective. It’s no accident that in the years after the civil war the membership really started to take off.

And Escrivá really ensconced himself with Franco’s brutal regime. As Escrivá began to gain celebrity, and as the movement began to grow on campus, Franco asked his officials to go out and investigate him, to look into his politics and his credentials. And this report was sent back up to the caudillo, reassuring him that Escrivá’s politics were—I quote here—“absolutely aligned with the regime.” Franco even asked Escrivá to host a private six-day retreat for himself and his wife. And, you know, after that, the movement of Opus Dei began to receive huge amounts of funding from the regime. Millions and millions of pesetas were diverted from public funds to support Opus Dei.

By the late 1960s, the vast majority of Franco’s cabinet was Opus Dei-aligned or in fact Opus Dei members. There were absolutely Opus Dei members who were more progressive, more liberal, and who were uncomfortable with the Franco regime itself. But as an organization, Opus Dei was extremely happy to cozy up to this brutal, murderous dictatorship that was killing tens of thousands of its political opponents in peacetime. They were striving toward a common goal: the complete re-Christianization of Spain and of the world

MO: You said Opus Dei is in sixty or so countries today. Can you give me a sense of what those countries are, how many members it has, what its diaspora looks like?

GG: By the late 1940s, Opus Dei had grown to a critical size in Spain, and Escrivá began very quickly to look at expanding into other countries. And he got permission from the Vatican to do that. His first port of call was Portugal, next door to Spain. Then he quickly started to expand across Europe. And thanks to the financial support that it had from the regime back in Spain, and thanks to the growing membership, he had the money to do it. And then later in the ’50s, when the group hijacked this national bank, Banco Popular, money was suddenly no object. So they expanded into the Americas. Latin America, with a common language, made it easier for Opus Dei members to fly over and to set up new networks there. But they got to the United States very early as well. By the late ’40s, they were already established. Initially in Chicago, but then they branched out to Boston, then New York, then Washington.

Today, Opus Dei is present in, I think, sixty-seven countries around the world: Australia, the Philippines, Japan, all across Africa, almost every single country in Europe and Latin America, Mexico, the United States, Canada. It’s on all of the six inhabited continents. In terms of membership, it says it has about 100,000 members around the world. There’s been a great deal of debate about whether or not those numbers are accurate. And certainly in the last few years we’ve seen large numbers of people leave the movement.

In the 1950s, when Opus Dei hijacked Banco Popular, money was suddenly no object.

MO: There’s a way in which one could say this is all fairly benign. People decide to join this organization. They give, what, 10 percent of their income, if they’re supernumeraries?

GG: Yeah, well, the supernumeraries are told to treat Opus Dei as if it was another child, and to kind of give appropriately for whatever you might spend on your child’s education or food and clothing or whatever.

MO: But you argue that they’ve done some pretty evil things. Let’s talk about them.

GG: First, the hijacking of Banco Popular in the 1950s really gave Opus Dei the financial firepower to expand to every corner of the world. There was this huge flow of hidden money, some of it secreted through places like Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Panama, with all of these shell companies that were used to finance the expansion of this network.

Banco Popular and the money has been fundamental in helping Opus Dei to really expand and create what is a global network of residences, schools, universities, and all kinds of hidden initiatives that kind of hide in plain sight, that don’t really advertise what they really are.

MO: And were these framed as donations from the bank to Catholic charities? Were they loans that the bank was making? Were they investments, insofar as all banks invest their deposits to make more money?

GG: It was a mixture of all those things. The bank was making donations every year, as many corporations do today. But it just happened that all the good causes were Opus Dei causes. But also the bank was making huge loans to open initiatives around the world. And helping to launder money out of Spain to various other jurisdictions around the world. Also, the chairman, who was a numerary member of Opus Dei, abused his position at the bank to set up all of these companies, and then he would carve up the bank’s own assets and effectively hand ownership over to Opus Dei. At one stage, the bank’s own headquarters in central Madrid, this multimillion-euro building, was actually owned by an Opus Dei foundation, and the bank itself had to pay rent to Opus Dei in order to carry on working in its own office.

MO: And all of this—this was never disclosed until you disclosed it? Because the people on the inside, who knew about it, were themselves Opus Dei numeraries?

GG: Absolutely, this was covered up for decades. People within the financial community, and financial reporters in Spain, long suspected that there were dodgy ties between Opus Dei and Banco Popular. But no one had managed to produce the receipts. But critically, when the bank collapsed in 2017, its assets were bought by a rival bank. And when I went knocking on this rival bank’s door saying, “Hey, can I look at the Banco Popular archives?,” they were like, “Sure, why not?” Because it had nothing to do with them.

MO: This strikes me as an enormous failure of the financial press over fifty years. I have to think that in the United States, if Chase or Wells Fargo were basically parceling itself off to a religious organization, somebody would have figured it out. That would be pretty tough to keep quiet in the face of Bloomberg and Dow Jones and The New York Times. But am I being naive? I mean, could this be pulled off anywhere, or was this a particularly complicit press corps?

GG: It takes time and a lot of effort to dig into these stories. Before I was even in a position to write a book proposal, let alone write the book itself, that took me three, four years, from getting interested in this and having the archives opened up to me, which of course made my job a lot easier, to being in a position where I was finally like, I can confidently go to a publisher and say that I can prove the story. Most journalists just don’t have the time for that kind of investigation.

But also, in Spain, in particular, the tentacles of Opus Dei run so deep that I don’t think it would have been possible for this story to really have emerged. I was in Spain just a few weeks back, promoting the book, and it’s quite eye-opening to see the influence of Opus Dei in action. Before I’d even got to Spain, there’d been this campaign launched in the right-wing media to basically discredit me and the book. So I can see how Opus Dei would have used its influence in the press, and used its network in Spain, to suppress the story or to divert journalistic attention.

MO: Has this been scary for you?

GG: There have certainly been legal threats against me and my publisher. In the months before the book came out, Opus Dei aggressively came after us and threatened me. “We’re going to make you bankrupt, basically, if you say these things.” But once the book came out, those threats went away. It was all about trying to intimidate us.

Given the evidence I had, the lawyers changed very, very little in the book. So, you know, that was quite a pleasant surprise. And hats off to Simon & Schuster and my other publishers for publishing this book, because it’s a book that doesn’t pull its punches. We make some quite serious allegations …

MO: Let’s get into those allegations. Human trafficking, for example.

GG: The human trafficking piece of this is probably the most interesting. I was completely unaware of this. When I was in the middle of reporting the book, my antennae were kind of peaked for anything to do with Opus Dei. And then one day I saw this story, which was run by the Associated Press, about some women in Argentina who had alleged that Opus Dei had recruited them whilst they were kids and basically entrapped them into this life of servitude. They were working fourteen-hour days, seven days a week, 365 days a year. They weren’t allowed to go out into this street on their own. They were cooking, cleaning for the elite members of Opus Dei.

MO: And living in a women’s quarters, attached to the male numeraries’ dormitories, right?

GG: Yes, and forbidden from ever speaking to the men or even having eye contact with the men. Scrubbing the floors, cleaning toilets for these elite members of Opus Dei. Many of these women had left and decided to seek compensation and an apology from Opus Dei. I saw this bit of news and I thought, “Oh, this is kind of interesting, but probably has nothing to do with what I’m looking into, which is the connections between Opus Dei and the bank.”

But then one day in the archives, I stumbled across this document which detailed how money from the bank had been used to set up this network of schools, what they called “hospitality schools,” which were used to entice young girls who were just twelve or thirteen, into this life of servitude. These women were recruited and promised a better life. They were taken away from their homes to these schools in the big cities, hundreds of miles away from their families. They were basically manipulated and coerced into joining Opus Dei as these “numerary assistants.”

So these women in Argentina have risen up and they filed a complaint at the Vatican. They sought compensation from Opus Dei in Argentina. Opus Dei turned them down. And so they went to the authorities, and just a few weeks ago, in fact, just a few days before my book came out, federal prosecutors in Argentina announced that they were formally accusing Opus Dei of having trafficked these girls. Now, I know from my reporting that this is just the tip of the iceberg. This is the first case. Authorities in other parts of the world are now looking at how these young girls were recruited as children and coerced into joining Opus Dei and then trafficked around the world to wherever Opus Dei needed them, where they would work effectively as slaves.

MO: Why couldn’t they leave?

GG: Well, because they had been coerced into joining the movement. And every minute of their existence was controlled and manipulated. They were cut off from their friends, their families. They had no money. They were cut off from the support networks, and they had absolutely no financial safety net to fall back onto. And they were told that if they left, then they would go to hell, and their entire families would go to hell. They were indoctrinated and coerced on a daily basis.

MO: Then there’s the financial impropriety.

GG: I’m convinced that the Banco Popular part of the story is just one part of this hidden financial open network. I would not be surprised if there are many other businesses out there that have been used over the years to fund Opus Dei’s expansion and to fund the network.

MO: And the schools.

GG: Opus Dei isn’t open about how it recruits people into the organization it runs. But there are hundreds of schools around the world that don’t openly advertise themselves as being affiliated to Opus Dei, but that in fact are. So many ordinary Catholics out there could well be sending their kids to what they think is just a good Catholic school in their local neighborhood, but which in effect are, you know, Opus Dei recruitment centers. Numeraries are posted to these schools and tasked with recruiting kids into the organization. This is going on today in the United States.

MO: I still want to know what the status of Opus Dei is in the United States is. Is this one of the bigger Opus Dei grounds, or is it smaller? Is Opus Dei, like Scientology, past its prime? Or is it bigger than ever?

GG: I think in many parts of the world Opus Dei is past its prime. The Opus Dei obsessions, and its philosophy, are completely out of date, not just for most people in the world but even for most Catholics. The priests and the numerary members of Opus Dei are obsessed with turning the clock back on things like the sexual revolution and general advances in society. And I think the vast majority of Catholics just aren’t interested in that.

But I think in other parts of the world, including in the United States in particular, there’s been a resurgence in a kind of traditional-values movement, epitomized by people like Kevin Roberts, Leonard Leo, even JD Vance. I think Opus Dei is dying in many parts of the world. But the U.S. in particular is one place where its philosophy, and particularly its kind of reactionary politics, seems to be in ascendance.