In his decades-long project to capture an image of humanity, Allan Crite (1910-2007) defined himself as a distinctive “liturgical artist,” relying on religious symbolism to relate his experience as Black and Christian in twentieth-century America. Crite moved to Boston with his parents as a toddler and remained there for the rest of his life, committing himself to the city and its citizens. While working as a draftsman at the Boston Naval Yard, he built a parallel career as a local artist.

A devout Episcopalian, Crite scattered Christian symbols throughout his work. He often depicted the most sacred figures (Christ, God, the Apostles) as Black, finding a hungry audience for such images even as his home city wrestled with a long legacy of discrimination against its Black residents.

Crite’s own identities and experience clearly informed his artistry, but many of his liturgical images seem removed from any single historical context. One drawing may contain robed saints, sword-bearing angels, steamships, and skyscrapers. Recognition of Crite’s work was often limited to the Boston area, but his visual language anticipated a new wave of theologians across the globe who sought to examine Christian teaching in new contexts. Liberation theologians of the 1960s and ’70s shared Crite’s impulse to transcend historical distinctions, finding in ancient traditions new mandates for a modern world. Today, Crite’s works still serve as unique renderings of his city and his faith.

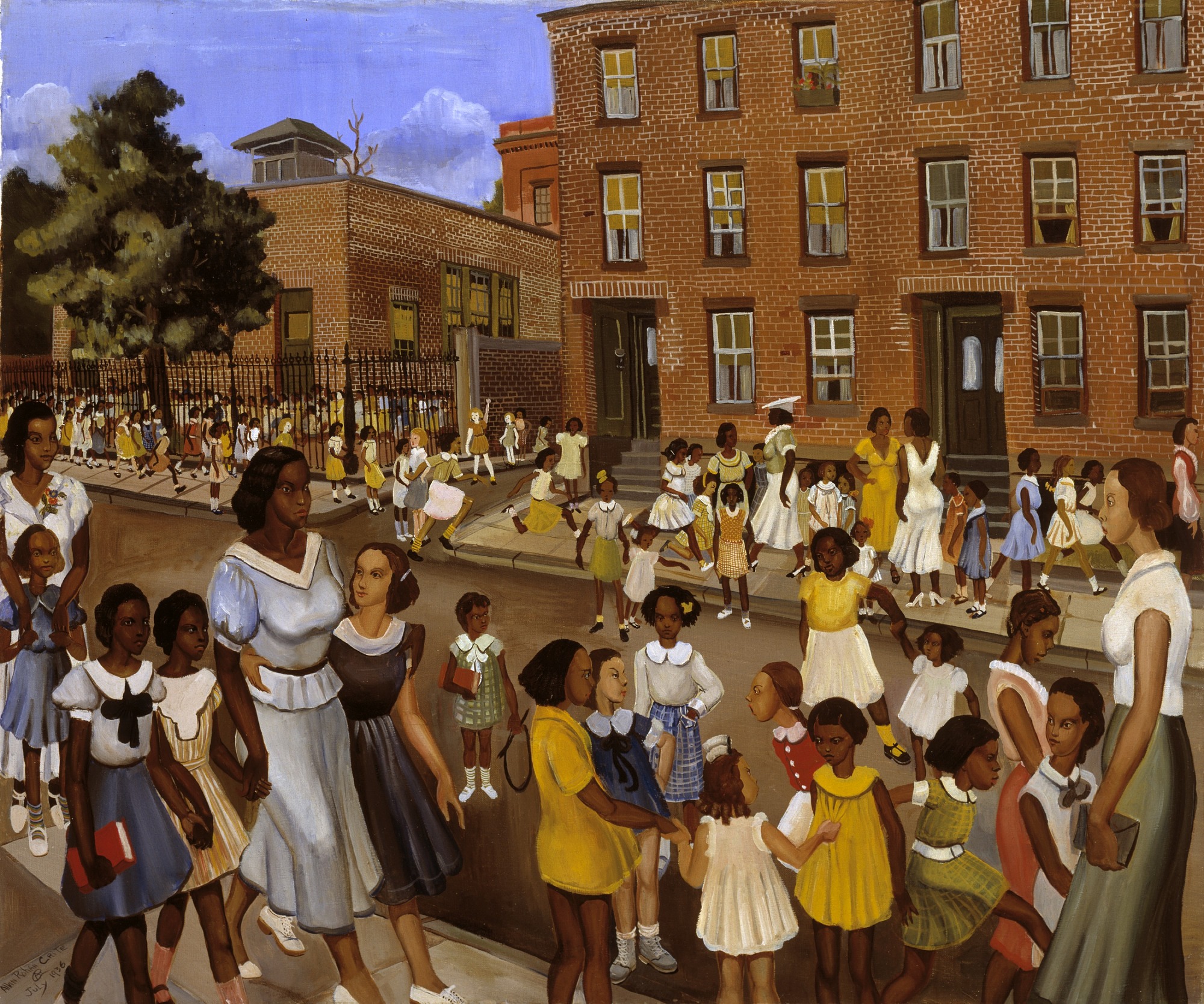

This watercolor marries two categories of work within Crite’s corpus: his neighborhood paintings and his liturgical works. In the neighborhood paintings (mainly produced earlier in his career), Crite sought, in his own words, to depict “the life of Black people in the city, just ordinary people as I see them,” disrupting a history of stereotypical depictions. His liturgical works, on the other hand, use the rituals and symbols of the Church to depict “the story of Man being told with the Black figure.” His liturgical art universalizes, placing the Black figure in roles historically monopolized by white figures. In “Streetcar Madonna,” these two styles—the representational and liturgical—meet. Madonna and Child sit on a subway car, the setting perhaps informed by his previous neighborhood paintings even as his subjects are distinctly Christian.

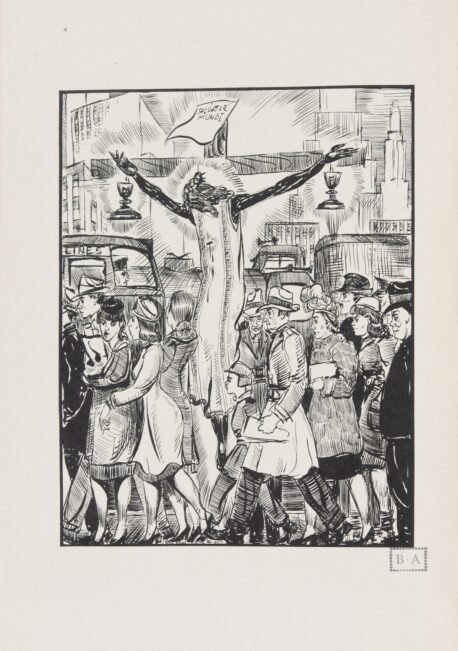

This image comes from a booklet published by the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts in a collection titled Is It Nothing To You?, a series of drawings inspired by text drawn from the liturgy of Holy Week. In all the images, as in this one, Christ is Black and the passersby white. More than twenty-five years before Boston schools were forced by court-order to desegregate, Crite had these liberatory images published by a powerful establishment of Anglo Boston. In his introduction to the collection, he assumes a tone remarkably similar to liberation theologians who, decades later, will call Christian communities to act against oppression. He demands that readers “put into action in ourselves and in society the full meaning of the drama of redemption.” For Crite and those theologians, that drama identifies Christ as a figure who works at the margins of society alongside the disempowered.

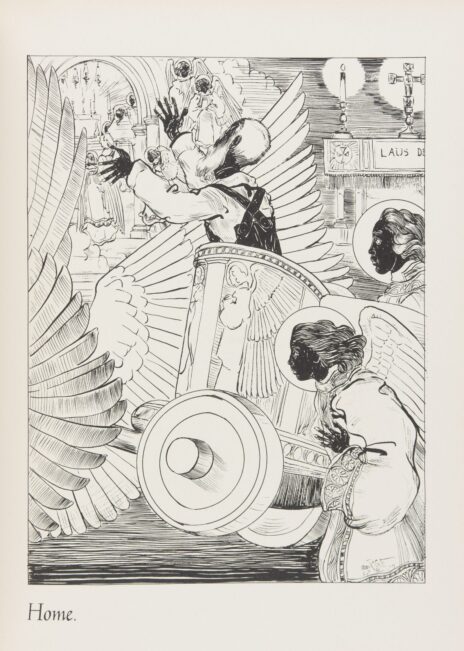

Crite published two volumes of illustrated spirituals with Harvard University Press. In both, he offers verse-by-verse visual interpretations of these songs, seeking to invest artifacts of history with new meaning. In a 1968 interview, he recalled a conversation with a young priest that demonstrated the necessity of this project: “The spirituals are slave songs [but] we sing songs of freedom,” Crite quoted the priest as saying. Crite then continued: “I appreciated his sentiments but I thought his facts were wrong. The spirituals are quite valid even today. The point of them was: they stressed the idea of a person’s humanity within a system which denied that humanity.” Crite captures that message in his liturgical style, with the subject reaching toward the altar as the site of communion with God. In so doing, he employs his Christian imagination to link the history of slavery with a contemporary struggle for civil rights.

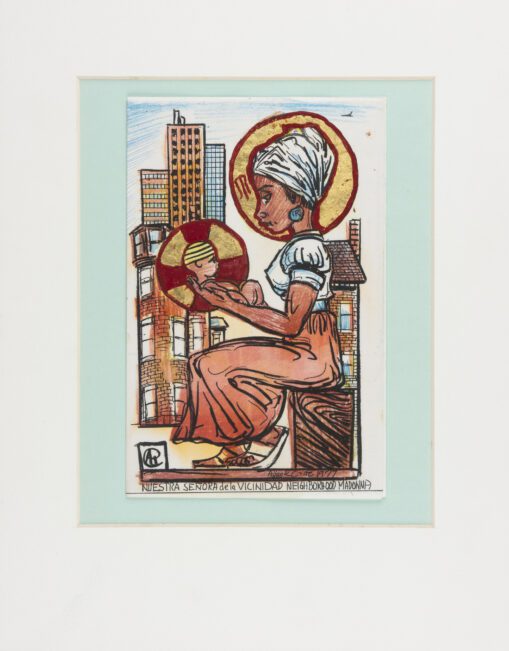

This print is a draft of an icon Crite created for St. Stephen’s Church, his place of worship for most of his adult life. The final rendition was on a gesso panel with a background of gold leaf. A sacred image of the Madonna, the model came from Crite’s Boston neighborhood, the South End, and the brick houses in the background depict architecture typical of that part of the city. As with his painting “Streetcar Madonna,” Crite here sought to depict a living faith, drawing on both religious imagery and the world of the mundane to fashion a sacred object of worship in which his neighbors might see themselves represented. Many of the works Crite made for Boston congregations—such as icons and illustrations for service programs—include captions in both Spanish and English to serve Boston’s growing Spanish-speaking population.

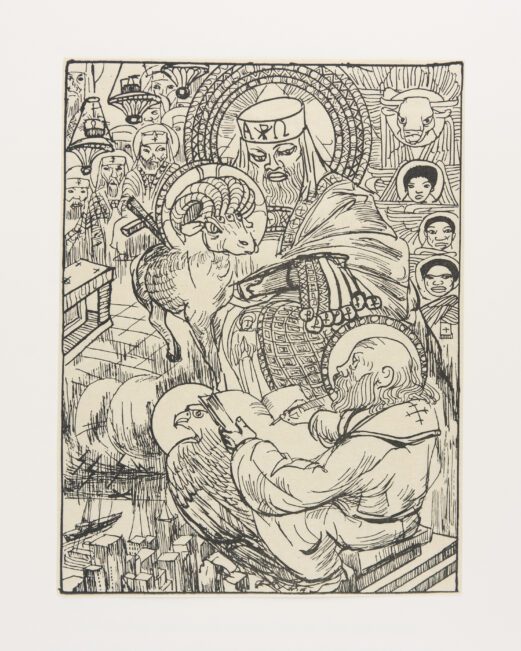

This later work is one of fifteen engravings Crite used to illustrate The Revelation of St. John the Divine, published in 1995 by the Limited Editions Club. The text comes from the biblical Book of Revelation, a notoriously obscure sequence of visions recorded by an ancient author. These visions provide rich imagery for an artist to explore, and Crite does so in his typical ahistorical manner, including many markers of modernity like skyscrapers and cargo ships. Liberation theologians also drew inspiration from the Book of Revelation, finding in this almost apocalyptic text a God who is involved in world affairs, casting swift judgment and fomenting change.