Thanks to Donald Trump’s attempts to link federal funding of elite colleges to their efforts to combat campus antisemitism, Jewish college students are in the news. And not for the first time. A hundred years ago, the Ivy League colleges launched systematic campaigns to deny entry to Jewish American applicants. In place of an admission rubric mostly based on grades, they added new categories that had the effect of discriminating against Jews, policies still in place at most of these institutions today.

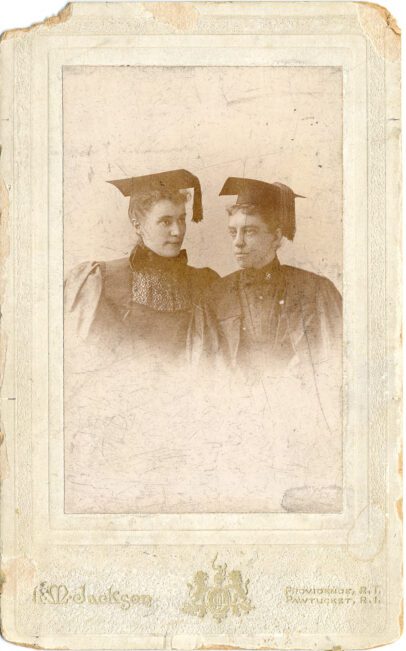

My family is part of this story. My grandmother, Sore (Sara) Sohn, was born in 1907 in Podolsk, Russia, one of eight children. At age six, she immigrated through Ellis Island to Providence, R.I., where she would attend the prestigious, public Classical High School and Brown’s women’s college (later called Pembroke) as it was advancing a mission to educate Rhode Island women.

Though there are decades of scholarship about anti-Jewish admissions policies at the (mostly male) Ivies between the world wars, less has been written about the women’s colleges affiliated with them, and the other prestigious women’s colleges of the time: Pembroke, Radcliffe, Barnard, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley, and Vassar. One night think these institutions were less antisemitic by virtue of their progressive mission—to educate women—but by and large they were not. Longtime Barnard College dean Virginia Gildersleeve was an antisemite, even as, between the world wars, the Jewish percentage at Barnard was around 20 percent. My original research in admission files at Pembroke reveals a similar, coordinated policy of antisemitic discrimination, especially among residential, or dorm, admission decisions.

My grandmother, a loyal Pembroke alumna who stayed in touch with classmates throughout her life, was delighted when I matriculated at Brown in the 1990s. In a conversation about her college experiences, she mentioned casually that there had been “Jewish quotas” but said, “It was the way things were.” I was so mystified by this idea of numerical limits on Jews that I became a public policy major at Brown (or “concentrator,” as we call it there), wrote my thesis on Jewish (1920s) and Asian (1980s) discrimination in Brown admissions, and delivered a commencement address about it. (Brown has a tradition of student commencement speakers.) It would not be a stretch to say I have a degree in Ivy League antisemitism—and yes, of course, I got honors.

If you’re new to the topic and have not listened to the excellent podcast Gatecrashers, which covers Ivy antisemitism in depth, here’s a condensed version of what happened at the Ivies from the 1910s until roughly the passage of the G.I. Bill in 1945. In the nineteenth century, America’s elite colleges moved from being training schools for ministers to being sites for upper-class boys to practice hijinks and merriment—with gentlemen’s Cs and widespread cheating.

But by the 1890s and early 1900s, the children of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, like my grandmother, were graduating from high school and looking to go to colleges. While Gentiles saw college as preparation for life in the leisure class, the growing number of Jews viewed it as an engine of social mobility.

Increasing numbers of Jews were being admitted into the Ivies. At Harvard in 1922, Jews made up a fifth of undergraduates. In 1920, Columbia had, allegedly, a Jewish percentage of 40 percent (exact numbers are impossible to come by). A popular college song of the late 1910s went: “Oh, Harvard’s run by millionaires / And Yale is run by booze / Cornell is run by farmers’ sons / Columbia’s run by Jews / So give a cheer for Baxter Street / Another one for Pell / And when the little sheenies die / Their souls will go to hell.”

My grandmother mentioned casually that there had been “Jewish quotas” but said, “It was the way things were.”

Brown had been founded by Baptists, and until 1926 the president was required to be a Baptist minister. During the 1910s and 1920s, many of the Jewish students lived in Providence with their families, and the other students began to notice this growing cohort. In February 1921, an entire issue of Brown’s humor magazine, The Brown Jug, was devoted to “carpet-baggers,” who were depicted as stooped, bespectacled, big-nosed men lugging their bookbags up College Hill (Brown is actually situated atop a hill). The real Brown men were depicted as handsome, tall, and elegant. “Brown Jugglers,” one article proclaimed, could “forgive a man for his long hair, for his glasses, and even for his carpet-bag, but when he does not show at least some interest in his college they cannot feel that he is a Brown man.”

All this anxiety about Jews was related to the fact the Jewish population in the U.S. was skyrocketing. From 1880 to 1925, the population of Jews in the U.S. went from 280,000 to more than four million, as the overall American population doubled. Jews were concentrated in the Northeast, home to all the Ivies. By 1927, Jews made up 13 percent of the combined populations of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island, but less than 2 percent of the population of the rest of the country.

Nativism was on the rise. Teddy Roosevelt preached racial superiority, and Harvard’s president, A. Lawrence Lowell, was vice president of the Immigration Restriction League, which worked to pass the Immigration Act of 1924. The act set quotas on Southern and European Jews and excluded Asians entirely. At Harvard, Lowell proposed a 15-percent Jewish quota—it was never enacted, although other measures would squeeze Jews out—and expelled Black students from the dormitories.

In 1927, Brown president William Faunce, noting an “obvious change” in the “racial and cultural environment of American college students,” wrote to the Brown trustees that “the American college is solemnly bound by legal and moral obligation to preserve its own identity, to be loyal to the ideas of its founders, and to receive at any one time only so many students of alien tradition as it can properly assimilate and guide.”

Afraid of alien, Jewish influence, Ivy administrators invented new admission criteria. These included geographical diversity (since most Jewish applicants came from large Eastern cities, recruiting students from more regions would reduce the Jewish population), in-person interviews, legacy preference, limits on scholarships, psychological tests, and greater recruitment at private and boarding schools. In Brown admission files, the strategy behind these policies was called “limitation of numbers,” because overall application numbers were rising, but the screening devices were specifically designed to limit Jews.

Soon, high school principals had to answer questions about Brown applicants’ neatness, punctuality, leadership, popularity, cheerfulness, and health. Questions on reference forms included, “Is the applicant attractive and well-bred in appearance and department?” and “Is the applicant the kind of man whom you yourself would welcome as a classmate in college?”

A popular campus ditty went: “Oh, Harvard’s run by millionaires / And Yale is run by booze / Cornell is run by farmers’ sons / Columbia’s run by Jews.”

Things were only a little better for Jewish women at Brown’s Women’s College, founded in 1891 and re-named Pembroke in 1928. As at Brown, the application initially required little: name, address, parents’ names, and high school grades. In-person interviews were not required.

The architects of antisemitism at Pembroke advocated for women’s education as a tool of empowerment but worked to squelch Jewish entry. They were Margaret Shove Morriss—nicknamed “Peggy Push”—who was Pembroke dean from 1921–1950 (and rumored to be the girlfriend of Rhode Island senator T.F. Green) and Eva Mooar, who became Pembroke director of admission and personnel in 1927. A Baltimore-born Quaker with a doctorate from Bryn Mawr, Morriss put Pembroke on the national stage. “Miss Morriss did not inherit the modern Pembroke,” Brown president Henry Wriston, who became president in 1937, once said. “She created it.”

Under Morriss and Mooar, the Pembroke application form was amended so that applicants had to report citizenship, religion, parents’ citizenship, religion, education, occupation, and birthplace. In interviews during the 1930s, as historian Karen Lamoree has written, Mooar evaluated applicants’ “personal appearance, family background, mental equipment, traits, financial, activities, interests, goal.” Here is a sampling of her comments, as compiled by Lamoree:

About an applicant to the Class of 1933: “Can’t tell whether Jewish or not.”

About an applicant to the Class of 1936: “Father has wavy hair, few front teeth and a marked accent. Says they speak German at home? Germans or Jews? Are blonde, so probably the former.”

About an applicant to the Class of 1944: “Tall, dark, rather attractive recognizable Jewish features.”

About an applicant to the Class of 1945: “Color just off-white. 32 years old. Mother, white—deceased. Father black. Sister married a white man.”

About an applicant to the Class of 1948: “Miss G. told her dorm situation not too good for large numbers (crowded) and told her we have quota.”

According to admission files, for the entering classes of 1930 to 1939, Pembroke was 16-20 percent Jewish, 49-60 percent Protestant, and 18-29 percent “Roman Catholic.” Even those Jews who tried to downplay their Jewish identity were clocked as Jews; a file from October 1935 breaks down the class of 1939 by religion, including the category “None – 4 (3 with Jewish parents).”

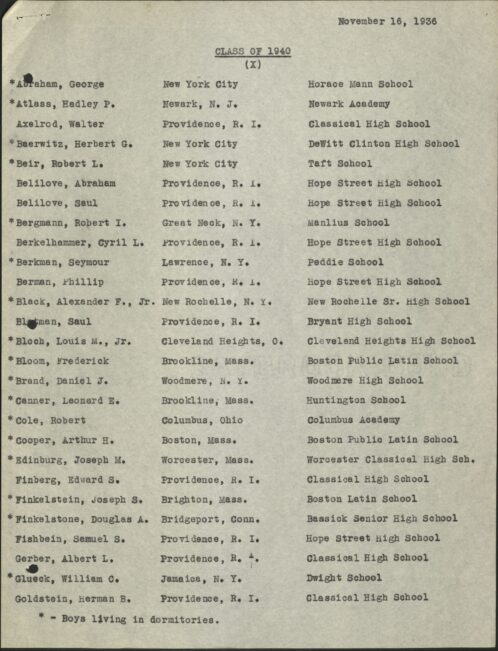

From 1936 to 1945, files on admission and matriculation statistics included the term “X.” Codes for Jews in admission files included X, or H, for Hebrew. Out of 75 rejected applicants in 1936, there were “22X = OK.” In 1937, 47 of 109 rejected applicants were Jewish. In 1938, 66 of 154 were Jewish.

The antisemitism focused attention on the dorms. The admission office tallied rejected and accepted Jewish dorm applicants, non-dorm Jewish applicants, and non-Jewish dorm applicants; Jewish and non-Jewish dorm applicants by state; and Jewish applicant percentage (“The H percentage [of applicants] this year has dropped 4% during the last month”).

1941: “[The] increase of 10 applicants over 1940 is all in non-X dormitory prospects.” 1942: “[T]he H dormitory situation will present no more of a problem than it did last year.” Pembroke also discriminated against Black dorm applicants—refusing all of them. One African American Pembroke dorm student light enough to pass as white was expelled when her race was discovered.

In 1942, Morriss wrote to Pembroke’s Corporation Committee, “We accept all [Jewish applicants] who come to us from Providence and enough others to make a proper proportion in each dormitory. We reject each year about 100 to 150 Jewish applicants, nearly all of whom are fully prepared. Pembroke College is popular with that race because we have such nice Jewish girls in our highly selective group and because they are well received here among the student body.”

“Germans or Jews? Are blonde, so probably the former.”

These discrimination proxies worked as well at Brown as at Pembroke. For the classes entering from 1930 to 1940, the Jewish percentage never topped 16 percent. In 1940, 11 percent of Jewish freshmen were Jewish.

Using a different measurement, from 1930 to 1938, Brown’s admit rate for self-identifying Jews (the number of Jews accepted divided by the number of Jews who applied) was 17-25 percent, while the admit rate for Protestants was 44-56 percent, and the overall admit rate was 36-45 percent. In other words, a Jew had less than half as much chance of admission as a Protestant did, and around half the chance of admission as the generic candidate did.

One of the policies used to limit Jews was to require the SAT. In 1938, Brown dean of admissions Bruce Bigelow suggested to Wriston, Brown’s president, a list of reasons that Brown should require the SAT. One was “An aid in handling X cases.” According to Bigelow, the admissions director at the University of Pennsylvania had told him “that it was the X problem which led Penn to require the S.A.T. Since the test results do not go to the boys themselves, the admission officers are better able to reject those applicants who should be refused. Students in one school are less able to compare the applicants and question why Jones was admitted and Smith refused. The X problem is unfortunately becoming more and more acute.”

Each year, Brown had to reject more Jewish applicants. Bigelow wrote in 1941 to dean of the college Samuel Arnold, “The ‘Jewish problem’ continues to increase! Twenty-nine percent of all the applicants were Jewish, and only fifteen percent of this group were accepted and entered. Of the non-Jewish group, fifty-three percent were accepted and entered.”

By the mid-1940s, references to X students disappeared from admission files. The G.I. Bill widened the pool of applicants, and, perhaps due to the Holocaust raising sensitivities around antisemitism, administrators dropped the quotas or became more secretive about them.

“Americanization” was the process of acculturating new immigrants to American life, or, as Emma Goldman put it, “teaching the poor to eat with a fork.”

My grandmother loved Pembroke College, and Pembroke seems to have loved her. A German major, Sara was a scholarship recipient, a member of Phi Beta Kappa, and an honors student. Her yearbook blurb said, “She has been brilliantly successful in her studies, but besides such achievement, she has patience and unselfishness enough to help her classmates and to perform outstanding work in Americanization. Sara’s energy will undoubtedly carry her far into success in the world.” “Americanization” was the process of acculturating new immigrants to American life, or, as Emma Goldman put it, “teaching the poor to eat with a fork.” Presumably, these courses were where my grandmother lost her Yiddish accent and acquired long Providence vowels.

After graduating from Pembroke in 1929, Sara taught in local schools, community centers, and the adult education department of the Rhode Island statehouse. In 1931, she applied for an academic job at the Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio, a female seminary. After receiving Sara’s materials, President Ralph Kiddoo Hickok, a Nebraskan, a graduate of Princeton Seminary, and a pastor, told her to visit campus to meet with him. Then he requested a recommendation from Pembroke. In a section of her recommendation form called “General Information,” her German professor, Robert McBurney Mitchell, lavished praise on her.

But in a section called “Confidential information (for use of Personnel Office only),” he wrote:

Miss Sohn has some Jewish traits of personality that are not attractive—is inclined to push in and get all she can at the least possible expenditure of effort. There’s a sort of efficiency in that, however, which one admires with some exasperation. Her voice is bad. Her approach lacks tact. But she dresses neatly and in good taste. In the right place she will do excellent work, but she should not be recommended for a position that cares for tact or one where a Jewess would not be acceptable.

When I read these words at twenty-one, I was shocked by the term “Jewish traits of personality.” Years later, I’m drawn to the second sentence, in which Mitchell sums up the antisemitic mind: Jews’ inherent pushiness is so efficient that it’s enviable, but in the inherent Jewishness of pushiness, it can only be a flaw.

With this paragraph, Mitchell doomed Sara’s job prospects at Western. President Hickock read Mitchell’s words and sent Sara the following letter:

I must cancel any suggestion I had made looking forward to a personal interview. This is merely because I discover that you are a Jewess and I think that probably you would not be happy in an institution such as Western College. I sincerely hope you will be willing to believe that this does not mean any prejudice against the Jewish race. Perhaps I may be justified in saying that my own studies have created a more than common interest in your people. This action is due simply because Western College is a Christian college where the religious life according to Protestant traditions is somewhat emphasized. With all good wishes and with regret for the trouble to which you have been put, I am very sincerely yours, President.

Maybe Hickok was right, and a Jewish immigrant from Podolsk would not have been happy in Oxford, Ohio, away from friends and family. But she had already gotten through four years of mandatory chapel at Pembroke, and maybe she wanted to expand her horizons.

Hickok’s sentiments indicated a corollary problem to discrimination in admissions: even those Jews able to get into elite colleges during from the 1920s to the 1940s often faced employment discrimination. And all women faced hiring discrimination, steered away from academia and toward teaching elementary and high school.

Sara gave up on Ohio and went on to receive a master’s in German education from Pembroke. My research indicates she was likely one of only ten or so female graduate students in her year. After receiving her degree, she moved to New York City and worked as an analyst at the National Bureau for Economic Research and the Institute for Life Insurance.

In the early 1960s, my father, a high school senior in Brooklyn, wanted to apply to Brown. Sara wrote to a friend in the alumnae office to ask, “Do the children of alumnae apply on a basis entirely the same as those of non-alumnae?” Her friend told Sara to write to the admission office and request information about an “early decision plan for sons of alumni and alumnae.” Thus my father, and presumably me decades later, benefited from legacy preference, a system originally devised to keep our people out.

One evening during my father’s first year, he was lying on his bed in his dorm room when he noticed flames coming through the bottom of the door. He leapt up, grabbed a towel, and swatted out the fire. I can’t say for sure it was antisemitism. “I’m pretty sure the guy who did it had a last name ending in a Roman numeral,” he later told me. In 1971, less than a decade later, Brown was 25 percent Jewish.

When I entered in the 1990s, the only hostility I felt as a Jew was from Jewish day school graduates who moved around in packs and said things like, “If you’re Reform you might as well be Christian.” I pulled away from Jewish activities and turned to theater. Although I didn’t feel very Jewish when I attended Shabbat services at Hillel, I did when I researched my thesis on antisemitism. There is nothing more Jewish than studying the people who hate us. I spent long hours in the library, davening over admit rates, overall percentages, and reports on “Jewish mortality”: the number, closely monitored by the deans, of Jewish students who dropped out. I felt alive and awake doing primary research, one question leading to another, with discoveries in each new folder. I also felt enraged, and my rage was premised on an equally powerful love of Jews and Ivies. The X students were literally climbing College Hill to get degrees that would bring them better lives. I believed they were more qualified than their WASP peers.

This past April, the media reported that the Trump administration intended to block $510 million in federal grants for Brown due to purported antisemitism on campus. A few weeks ago, Brown’s president, Christina Paxson, who was raised a Quaker but converted to Judaism in college, signed a statement opposing the Trump administration’s attacks on universities and calling the cuts “unprecedented government overreach and political interference now endangering American higher education.” Brown is suing the National Institute of Health and the Department of Energy to stop funding cuts. Like Harvard, it is fighting back.

In part inspired by Pembroke, my grandmother continued her education throughout her life, taking classes at every opportunity. I believe she would support Brown in fighting to preserve its existence, its meaning, and its impact on the Rhode Island economy.

What the Trump administration really wants to do is to exterminate academia. Antisemitism on campuses, though real, is to the Trump administration a smokescreen. Michael Roth, president of Wesleyan, has called these policies the “instrumentalization of Jewish fear.”

What struck me as I learned about my grandmother and her peers’ experiences at Pembroke in the 1920s was the lack of fear, the boldness, in even wanting to enter a world previously cut off to them. The Jews wanted into the Ivies because the Ivies had value. It just took the Ivies time to realize that the Jews had value, too.