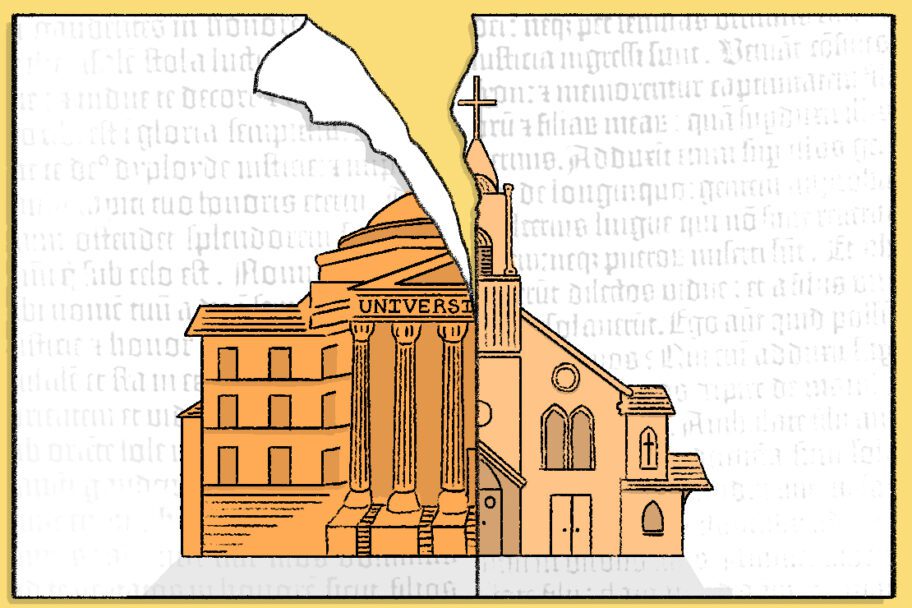

In the decade since the Supreme Court affirmed the right of same-sex couples to marry, theologically conservative Christian institutions have been severing their relationships with each other. The year of the Obergefell decision, Union University, Oklahoma Wesleyan University, and The Master’s College and Seminary quit the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities (CCCU), the main consortium of evangelical schools, accusing it of being too lenient with members that had added sexual orientation to their non-discrimination policies. By the end of 2015, Eastern Mennonite University, Goshen College, and Bluffton University had also left the CCCU—because it was too conservative for them. In recent years, similar cracks have started to open within denominations. For example, the Christian Reformed Church recently gave confessional status to its traditional interpretation of human sexuality. The Synod 2022 vote to confirm that same-sex behavior was prohibited by the Heidelberg Catechism’s reference to “unchastity” has led a growing number of clergy and congregations to disaffiliate from the CRC.

That debate affects professors at Calvin University, who have to affirm the Heidelberg Catechism and other confessional documents. That’s no small implication: Calvin is a historic center of Reformed Protestantism—the tradition influenced by Dutch Calvinism—in the United States and one of the country’s most widely respected Christian universities, the erstwhile academic home of influential scholars like philosophers Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff and historians George Marsden and Kristin Kobes Du Mez. While members of the Calvin faculty have historically been able to file statements of “confessional difficulty,” room for dissent from denominational stances seems likely to shrink.

All of which led one of Calvin’s most prominent professors to float the idea of the university separating from the CRC. “Should we spend our energy crafting policies for convictional exceptions to the denomination’s doctrine,” asked philosopher James K. A. Smith in the Calvin student newspaper last month, “or should we be thinking creatively and strategically about how to unhook the university from denominational control?”

“Divorces happen all the time, including institutional divorces,” Smith concluded. “While I would hope for an amicable separation, some fights are worth having. The Calvin project is worth the fight.”

Denomination/university divorces are not unknown. And while hundreds of American institutions of higher learning maintain a religious affiliation in a post-denominational age, Smith is not alone in wondering why a Christian university would continue to “bind itself to a shrinking church body that provides infinitesimal financial support and fewer and fewer incoming students.”

I’ve asked myself similar questions about the relationship of my university (Bethel) with its denomination (the Baptist General Conference, now doing business under the name Converge). Not because of the latter’s stance on sexuality and marriage, which I support as a responsible and thoughtful interpretation of Scripture, but because it’s unclear that the practical benefits of a denomination/university partnership as close as ours still make worthwhile the opportunity costs of the arrangement. I don’t know if Converge is “a shrinking church body,” but it’s certainly providing far less financial support and many fewer students (even seminarians) to Bethel than it did in previous decades. Meanwhile, continuing to require all employees to agree with or support the articles in one denomination’s particular affirmation of faith undeniably makes it harder for Bethel to hire the best possible Christian faculty, staff, administration, and leadership.

It’s for our trustees and leaders, not any faculty member, to answer questions like Smith’s. I just hope that they ask them, regularly and in good faith. Even if the ensuing discussion doesn’t change the status quo, it would place the decades-long partnership on a foundation stronger than unquestioned custom or unexamined inertia. And if the benefits no longer outweigh the costs, then decision makers at both institutions should consider that there are changes to the relationship less drastic than total separation; even Smith allowed that a “divorce” between the CRC and Calvin “could make a new friendship possible.”

But to the extent that denominational universities should entertain any meaningful change to their traditional church partnerships, I’d suggest that they think in terms of three metaphors other than husband and wife: that of parents and their adult children, of siblings in tension, and of teachers and students. None is perfect, but each may help us to see the relationship with greater clarity and nuance—without inspiring the rancor that inevitably resulted from Smith’s “divorces happen” comment.

Divorce implies marriage, a covenant between two adults. But in American religious history, Christian universities like Bethel and Calvin have typically been the academic children of ecclesial parents. Conservative members of Dutch Reformed churches split in 1857 to found the CRC, then established Calvin College after the Civil War. The chronology is a bit misleading in the case of my institution, since the tiny seminary that grew into Bethel was founded a few years before what was originally called the Swedish Baptist General Conference was itself incorporated, at the other end of the 1870s. But that seminary was certainly an offspring of the immigrant movement that had been planting Swedish Baptist churches in the U.S. since 1852; it existed to train ministers and missionaries for those churches.

Bethel outgrew that founding purpose, especially after the seminary merged with a secondary school that developed into a four-year liberal arts college. While our longest-serving president, Carl H. Lundquist (1954-1982), liked to insist that Bethel in the mid-twentieth century remained the Baptist General Conference “on mission in education,” its maturation was already pulling it in other directions. Over one hundred fifty years after its birth, Bethel is still the offspring of Converge, but it is an adult child with its own responsibilities—plus relationships with accrediting bodies, school districts, hospital systems, government agencies, corporations, and other institutions that arguably have more direct impact on its day-to-day work than the university’s ties to its denomination.

Families can grow apart, even to the point of estrangement. But in the normal course of things, it seems reasonable to expect denominations and their colleges to mature into a relationship akin to that of parents and their adult children: still deep and meaningful, but different from that of earlier years. The danger within this metaphor comes when denominations continue to demand that their academic children respect their beliefs and values, without in turn respecting those universities’ freedom to chart their own paths.

In a sense, Christian colleges share the “family business” with their denominational parents, since they also participate in the larger mission of Jesus Christ in this world. But as we often have to remind our constituents, the Christian college is not a church. It has a different calling or charism than the denominations, congregations, and other groups with whom it shares the Body of Christ. So perhaps it would also be helpful to think of Christian universities and their sponsoring denominations as sisters and brothers in Christ.

This metaphor came to my mind on a recent Sunday morning, when our neighborhood church installed its new senior pastor. With the rest of that (Lutheran) congregation, I was happy to receive my brother Kent “as a messenger of Jesus Christ,” to respect him “as a servant of Christ and a steward of the mysteries of God,” and to commit to help him “in carrying out this ministry.” While I can hear echoes of those charges in my own callings as Christian college professor and historian, I know that Kent has a vocation, office, and set of spiritual gifts that are as distinct from mine as they are from the musicians, attorneys, accountants, stay-at-home parents, and retirees who were sitting near him in that same service.

Are we divorced spouses—or are we siblings in tension?

No more than the eye and the hand or the laity and the clergy, the denomination and the Christian university cannot say to each other, “I have no need of you” (1 Cor 12:21). But nor can the one tell the other, “Your calling is the same as mine” or “Your role is subservient to mine.” For both are enabled by the same Spirit to pursue the same mission … through different activities, different services, and different gifts.

But the siblings metaphor carries another pair of implications that ought to live together in faithful tension. As we installed our new pastor on Sunday, we also committed to “strive to live together in the peace and unity of Christ.” I appreciate that the Bethel of Lundquist’s era began to hire professors from outside the denomination, opening the faculty to non-Baptist scholars like me and modeling—in ways that its denomination can’t—how Christians who can never entirely “be in agreement” can still “be knit together in the same mind and in the same purpose” (1 Cor 1:10). At the same time, receiving the blessing of that hospitality is part of what makes me recoil from Smith’s divorce metaphor; maintaining unity within and between Christian communities is not the one thing needful, but it’s always worth striving for.

When writing about Bethel’s history, I’ve often quoted from Carl Lundquist’s 1961 report to the Baptist General Conference, in which he reflected on the importance of freedom in a Baptist college setting—including “the teacher’s freedom within the stated limits of the religious objectives of the school.” As both a loyal Conference Baptist and the president of a modernizing college and seminary, Lundquist recognized that Bethel had to strike a “delicate balance between the responsiveness a school ought to give to its constituency and the leadership a school ought to give to that constituency,” neither settling for “dull mediocrity” that never upset constituents nor moving out too far ahead of those fellow Christians.

I do understand the ongoing need for Lundquist’s “responsiveness.” Again and again in more than two decades at Bethel, I’ve heard trustees and leaders warn us that we need to take seriously the concerns of constituents who suspect us of theological or mission drift. So I can appreciate that being anchored by a denomination’s affirmation of faith keeps us from going adrift, and sustains what Lundquist called “sturdy confidence in the spiritual and intellectual integrity of the school.”

But I almost never hear those same constituents acknowledge the other half of Lundquist’s balance: that Bethel exists to give “leadership” to its denomination and other Christian constituents. He argued in his 1961 report that Bethel had to sustain its “sturdy confidence” among Convention folk, so that it could fulfill its mission during those moments “when it raises disturbing questions, engages in rigid self-evaluation, expresses dissatisfaction with the status quo and seeks less popular but more consistently Christian solutions to the problems that vex mankind.”

That list of activities makes me think that Lundquist didn’t so much see Bethel and the Conference as leader and follower but teacher and student. And maybe not just the most literal version of that relationship: the denomination entrusting its teenaged children and future pastors to the educational care of Bethel professors with whom they shared a core set of beliefs and values. As experts in their fields, constantly working to integrate faith with learning, ought not our faculty raise disturbing questions in the minds of people in Converge, even to prompt “rigid self-evaluation”? Shouldn’t scholars who have insights to bring from the cutting edges of the sciences, arts, humanities, and professional fields—not to mention theology, biblical studies, and Christian ministry—help the denomination and its congregations to view the status quo more critically and to seek “less popular but more consistently Christian solutions to the problems that vex mankind”?

As in any pedagogical relationship, Bethel’s teachers would also learn from their denominational students: e.g., the hopes and fears that animate today’s church, or changes to the ecclesial, familial, and other contexts from which our tuition-payers come. Meanwhile, our churchly “students” would raise questions that we professors might wish to avoid, and challenge the assumptions pervasive to higher ed’s status quo.

Institutional relationships do adjust over time, as their founding conditions change, and some even end in something akin to divorce. But I’d rather lean into these other metaphors, each of which might allow more mutual understanding and trust between denomination and university, even if their relationship looks different in the twenty-first century than in the past.