Since its founding, Israel’s effort to define Jewish status—codified in the Law of Return, which determines eligibility for Israeli citizenship—has had profound consequences for Jews inside and outside its borders, making it a reliable pain point between Israel and American Jewry decade after decade. Perhaps one of the most emotional episodes in the ongoing drama took place following Israel’s 1988 elections, when ultra-Orthodox parties made their participation in the government coalition contingent on a legislative change requiring the state authority to recognize Orthodox conversions exclusively.

The proposed amendment triggered an unprecedented backlash from American Jews, who brought their voice directly into Israeli politics. This crisis eventually led to a secret negotiation process between Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir’s office and the heads of the three major American Jewish religious movements—Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox. Following nearly a year of talks, the negotiation team reached a compromise that Israel’s ultra-Orthodox rabbinate was prepared to accept and the Israeli government to adopt.

And then the entire process fell apart.

The founding of the Jewish state, born from the ashes of six million lives lost, placed Israel as the protector of the Jewish people’s future. Israel’s intentionally vague 1950 Law of Return gave every Jew the right to citizenship. A 1970 amendment defined a Jew as anyone born to a Jewish mother, as dictated by Jewish law, or who converted. It left open whether non-Orthodox Jewish converts, while eligible for citizenship, would be recognized as “Jews” by the state. The amendment’s “grandparent clause” ensured citizenship to anyone with one Jewish grandparent or married to a Jew.

The amendment’s failure to recognize progressive movements’ religious authority struck at the heart of American Jewry’s budding relationship with Israel. After Israel’s stunning victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, American Jews increasingly positioned Israel as their source of Jewish pride, identity, and security. Israel’s refusal to protect the legitimacy of Reform and Conservative Judaism wasn’t merely a bureaucratic issue affecting a small number of converts. As longtime American Jewish leader John Ruskay explained, “[The debate around] ‘Who is a Jew’ gave us a sense that the Judaism that [the majority of American Jews] embraced was not acknowledged. That conversion by [non-Orthodox] rabbis wouldn’t be recognized was a blow, a punch in the gut, not because it was a legal thing. It was about [American Jews’] ideology and their being in the context of Jewish identity …”

Israel’s refusal to protect the legitimacy of Reform and Conservative Judaism wasn’t merely a bureaucratic issue affecting a small number of converts.

By the late twentieth century, Reform Judaism accepted patrilineal descent, and Reform and Conservative Judaism both worked hard to welcome those in interfaith marriages. These positions diverged sharply from Orthodox practice and Israeli social norms. As American Jewry turned simultaneously towards Israel and progressive Judaism, the divide between American Jews and Israel’s establishment became increasingly messy.

Tensions came to a head in 1988. Twelve days before Israel’s November elections, the Brooklyn-based leader of the Chabad/Lubavitch Hasidic movement, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, endorsed the ultra-Orthodox Agudat Yisrael party. Explaining Schneerson’s decision to The New York Times, Yehudah Krinsky, the Rebbe’s spokesperson, said, “Jews didn’t go to the gas chambers or suffer the Inquisitions so that their children could be assimilated.”

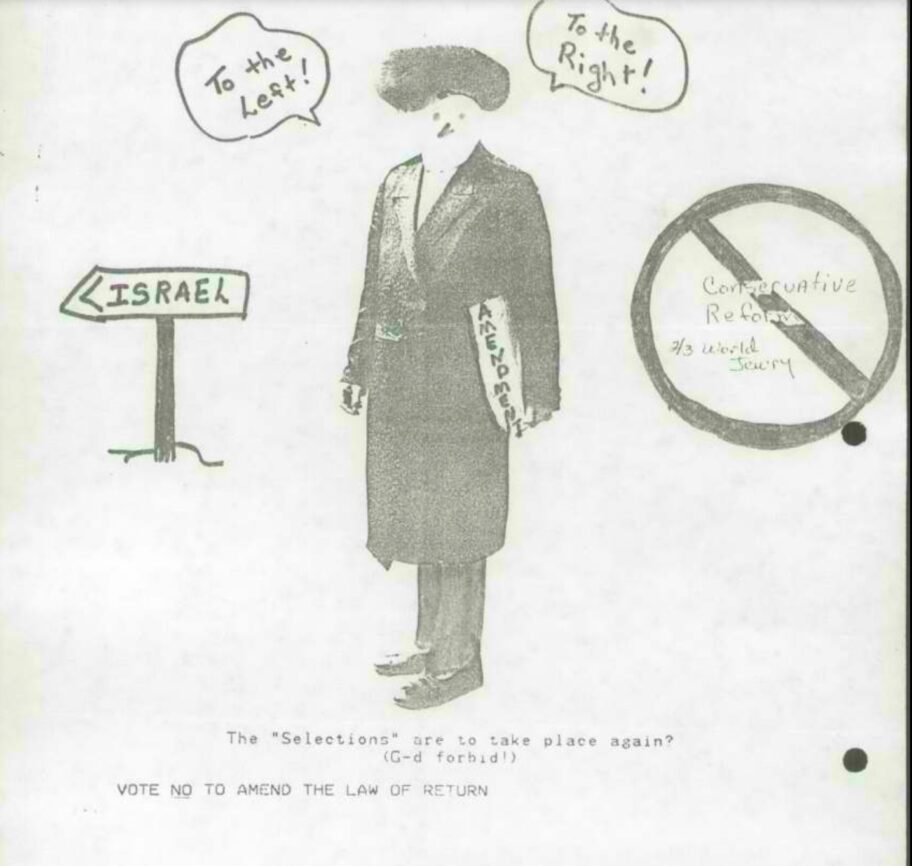

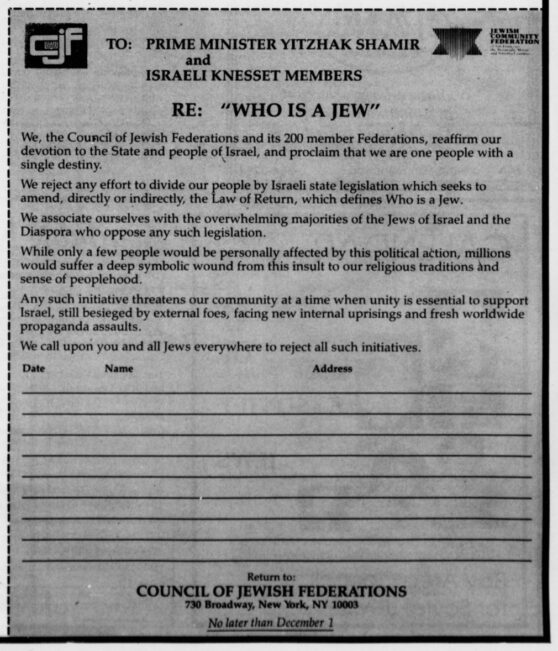

With Schneerson’s push, the election results kept Shamir in power, while giving the ultra-Orthodox parties enough seats to demand Orthodox control over Jewish status laws as a condition for joining Shamir’s government. As Israeli coalition talks were held, American Jewish leadership gathered in a panic at the Jewish Federations’ annual General Assembly. Delegations to Israel were organized, and petitions were drafted for distribution across North America.

Shoshana Cardin, leading a high-level philanthropic delegation to lobby the Israeli government, told the news service JTA that “anger” was the wrong word to describe the depth of American Jewry’s emotions. Instead, it was “pain and anguish that the unity of the Jewish people, Klal Yisrael, could be destroyed, could be shredded.” Israeli leaders must be aware of the “tremendous, tremendous trauma that will take place if we are not understood.”

Former San Francisco mayor and future senator Diane Feinstein told The Jerusalem Post, “When I converted to Judaism in 1949”—her mother’s family had practiced Russian Orthodoxy—“I learned that it was my right as a Jew to return to this land if I wanted to. Now I hear that my identity as a Jew and my right to return are threatened by an act of political expediency.” Denver rabbi Stanley Wagner recalled Knesset halls filled with “scores of American Jewish delegates [… ] with blood in their eyes.”

The Times reported, “The trips were so hastily planned that some American rabbis had to ask colleagues to fill in for them at weddings and funerals. One Reform rabbi rushed to the airport after a meeting in Jerusalem so that he could get home to San Francisco in time for his daughter’s bat mitzvah.”

Hundreds of letters to Israel’s government—mostly against and some for changes to the status quo—were sent by mail and by fax from American Jewish households. One such letter, from William A. Wolfson of Jackson, Mississippi, to Shamir, read, “It was with a heavy heart that I read about the possibility of the change in the Right of Return Laws of Israel. This feeling of sadness slowly turned to outrage as I realized some of the implications of this change. My wife is a convert (Reform) and we have two sons that we are bringing up in what we consider to be a Jewish home. Now I am being told that they are no longer to be considered Jews and Israel is no longer the land of hope, the backbone of their faith … ”

Donors such as multimillionaire Peter Kalikow publicly threatened to withhold donations to Israeli institutions. He told JTA, “It hurts me to do this. But somebody must stand up. It’s the only way to get their attention over what I think is wrong.”

Yosi Achimeier, Shamir’s spokesperson, told The Times that Shamir was ‘looking for a way to calm American Jewry.’ The Prime Minister assigned the task to his Cabinet Secretary, Elyakim Rubenstein.

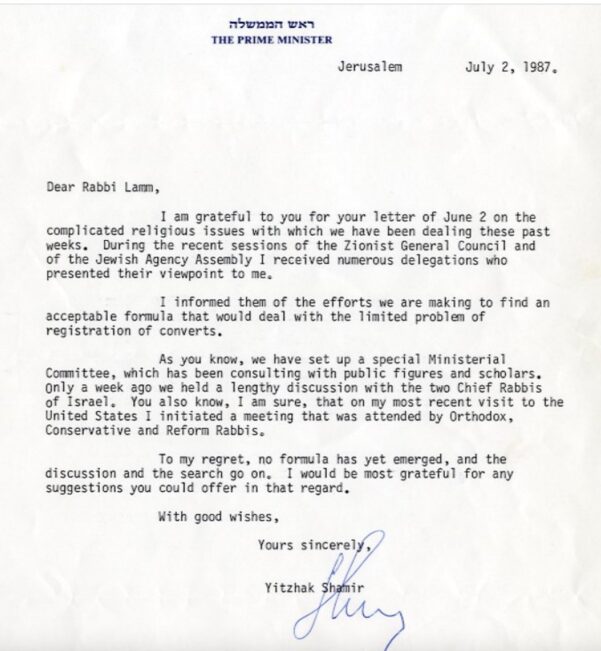

“[The idea] started with Lamm and me,” Rubinstein said in a recent interview, referring to Norman Lamm, the former president of Yeshiva University. Rubinstein, who later led the peace process with Jordan, and served as Israel’s attorney general and vice president of the Supreme Court, is one of the few voices left to recall what took place.

Lamm and Rubinstein believed that the heart of the crisis was in America; if American Jewish institutions could ensure that potential immigrants to Israel received an Orthodox conversion on U.S. soil, even if their conversion process was with a progressive movement, then it would essentially become a non-issue for Israel.

They proposed the creation of an American-based joint selection committee along with an Orthodox religious court, which would produce conversions according to strict Jewish law, for the Israeli rabbinate to oversee and the Israeli government to accept.

This plan would require the buy-in of all three major religious movements. As such, Lamm and Rubinstein suggested creating a quiet negotiating process between the streams’ representatives and the government. The prime minister agreed to the process. He called for the government to table the issue for eighteen months as talks transpired.

As Rubinstein wrote to Lamm, “If there is any chance of promoting an understanding between the various trends in the U.S., time is definitely of the essence. There are two separate but related issues: the attitudes in American Jewry and the question of legislation in Israel. The ideal solution should address both.”

That December, they began to assemble the team. Representing the Orthodox camp were Lamm and Louis Bernstein, president of the Religious Zionists of America and a Yeshiva University professor. Ismar Schorsch, chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, and Shamma Friedman, dean and director of JTS’s Jerusalem campus, represented the Conservative movement. Reform movement leaders Alfred Gottschalk, dean of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, and Walter Jacob of Rodef Shalom Congregation in Pittsburgh, completed the team. Each member was a highly respected rabbi and scholar in their own right. Rubinstein would represent the prime minister, coordinate with the relevant Israeli players, and work directly with the movements.

Per Schorsch’s request, each participant received a personal letter from Shamir, in which he wrote, “I am following very attentively these developments and will do what I can to aid in all of your success. You deserve a personal well done for strengthening the unity of our people, and bringing about cooperation on additional matters.”

The Israeli Chief Rabbinate agreed to passive involvement. In an internal memo to Bernstein, Chief Rabbi Avraham Shapira wrote that finding a solution was “not his business,” and he would “recognize anything approved by three recognized Orthodox rabbis in America.”

Through the spring and summer of 1989, the team worked toward a compromise, holding in-person meetings and conducting an ongoing flow of letters and phone calls.

Rubinstein traveled constantly between the parties, while meeting with Orthodox rabbis in Israel and the U.S. for their support. “We went to the end of the world trying to reach an agreement,” he recalled. “There wasn’t a rabbi’s door that we didn’t knock on.” This included a visit to Schneerson’s Brooklyn headquarters.

“He did not want to deal with it,” Rubinstein said of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. “He told me in Hebrew with a Yiddish accent, ‘Mah she huya huya’—what was, was. Defend the land of Israel. He was most interested in dealing with the diaspora …”

Hundreds of letters to Israel’s government—mostly against and some for changes to the status quo—were sent by mail and by fax from American Jewish households.

On September 11, 1989, a memorandum of understanding was drafted. It began: “We, the undersigned, have met to discuss the necessary agreements for conversions of perspective [sic] [immigrants], in order to enable them to be fully accepted in Israel for all purposes.”

At this point, the proposal was still only known in select circles. Then, on October 13, the New York-based Yiddish weekly Algemeiner Journal broke news of the process, publishing a false internal draft proposal including forged signatures. Backlash immediately erupted.

The negotiators—from Jacob to Lamm—denied the Algemeiner report as “fraudulent” and a “forgery.” According to Rubinstein, despite attempts to correct the false report and find the source of the leak, the truth held little weight. The report prompted prominent Orthodox voices to adamantly reject the agreement’s basic concept.

The drama was brought into the heart of Yeshiva University politics. On October 20, The Jewish Press reported, “Eleven roshei Yeshiva of YU have signed a document expressing their opposition [to the plan].” An internal memo from the time reported that the head of YU’s rabbinical school threatened to resign and take with him two hundred students if the plan went through.

Moving into 1990, while numerous attempts were made to restart the negotiations, much of the previous year’s goodwill had eroded. None of this would matter anyway, as Shamir’s government collapsed in March. With the end of the coalition came the end of the process.

In 2025, the issue of “Who is a Jew?” remains volatile and pertinent. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1990 brought thousands of new immigrants to Israel, many of whom were not Jewish according to religious law. Between 1990 and 2020, 36 percent of immigrants from the former Soviet Union were not considered Jewish. Today, there are nearly 500,000 Israelis who are officially listed as being of “no religion.” “Who is a Jew?” has become far more relevant as an Israeli social issue than it was in 1988.

Since then, the gap between American Jewry and Israel has only expanded. According to the 2021 Pew study, 70 percent of non-Orthodox American Jews intermarry. Ever-rising numbers of American Jews will not be considered Jewish by religious law.

While droves of American Jews are not immigrating to Israel any time soon, the crisis was never technical. It was and remains a crisis of identity, of Israel’s role as the home of the Jewish people, and of the message the nation-state sends to Jews around the world about what it means to belong.

As Rubinstein, the man who once calmed American Jewry, concluded, “It is essential, critical to the State of Israel, for there to be continual, true dialogue with world Jewry.”

In the aftermath of the Hamas attacks of October 7, 2023, the fracture lines between American Jewry and the Jewish state have never been more exposed—nor more dangerous. As intertwined crises engulf the world’s two Jewish centers, the capacity for Israeli and diaspora leadership to effectively communicate and address shared internal and external challenges isn’t merely desirable; it’s vital.