The second floor of the Rhea County courthouse in the sleepy town of Dayton, Tenn., is rather unremarkable, a cavernous space with windows opening out onto the courthouse lawn. The redbrick building itself was constructed in the early 1890s and includes a bell tower that, from a distance, could be mistaken for a steeple.

In July 1925, however, this unremarkable place attracted the attention of the nation, as two legal titans squared off in the Scopes trial, which for decades—until the O.J. Simpson proceedings in 1995—was unquestionably the trial of the century. Chicago radio station WGN, with its clear-channel signal, carried the proceedings live, and the phalanx of journalists, led by the irascible H.L. Mencken of The Baltimore Sun, characterized the trial as a clash between rural and urban America, between fundamentalism and modernity, between religion and science. On its birthday, the Scopes trial is more relevant than ever.

On Jan. 21, 1925, John Washington Butler, a corn and tobacco farmer and member of the Tennessee House of Representatives, introduced a bill that would outlaw the teaching of evolution in public schools. Section one of the bill provided that “it shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species had landed in American bookstores on Nov. 24, 1859, and the entire supply of 1,250 copies had sold out by day’s end. The onset of the Civil War blunted somewhat the effects of Darwin’s ideas, but by the closing decades of the nineteenth century, American Protestants had begun to choose sides. Many Protestants discerned no conflict in harmonizing the Genesis accounts of creation with new understandings in science. As philosopher John Fiske said, “Evolution is God’s way of doing things.”

Some evangelicals, however, were wary of Darwin’s theory. Taken to their logical conclusion, Darwin’s ideas undermined evangelicals’ traditional, literalist approach to the Scriptures. If the Genesis accounts of creation could no longer be regarded as history, these Christians reasoned, then the credibility of the remainder of the Bible might also be suspect. Perched on the precipice of the dreaded slippery slope, many evangelicals resisted Darwin’s evolutionary theory, first by asserting the literal, historical accuracy of Genesis, then through legislation similar to Butler’s proposal to halt the teaching of evolution in Tennessee.

The bill passed the House a week after it was introduced; the vote was 71 to 5, and on March 13 the Senate approved it 24 to 6. Austin Peay, the governor of Tennessee, considered by many to be a liberal, was reluctant to sign the bill. He relented, however, with the understanding that no attempt would be made to enforce it. Peay signed the Butler Act into law on March 21, 1925.

On the Scopes trial’s birthday, we can say that the Scopes trial seems more relevant than ever, the original template for conflicts that remain unresolved after a century.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) quickly decided to challenge the law and advertised for schoolteachers who might be willing to stand trial. Some local boosters in Dayton, a small town that had fallen on hard times, saw this as an opportunity to get some publicity. They summoned a young teacher from the local high school to Fred Robinson’s drugstore, plied him with a fountain drink, and asked if he would be willing to be charged with violating the Butler Act.

John Thomas Scopes, a native of Paducah, Ky., was the football coach at Rhea County High School, and he occasionally stepped in as a substitute teacher. He couldn’t recall whether he had actually taught evolution during one of his substitute assignments, but he nevertheless agreed to stand trial. The local constable was summoned to arrest him, whereupon Scopes left the gathering to play a match of tennis.

William Jennings Bryan, a devout Presbyterian, a three-time Democratic nominee for president, and Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state from 1913 to 1915, volunteered to assist the prosecution, alongside both the present and past attorneys general of Tennessee. The ACLU retained the services of an all-star defense team that featured Clarence Darrow, perhaps the best-known attorney of the era, who had lost his own bid for Congress in 1896 by a hundred votes, likely because he was campaigning so avidly for Bryan.

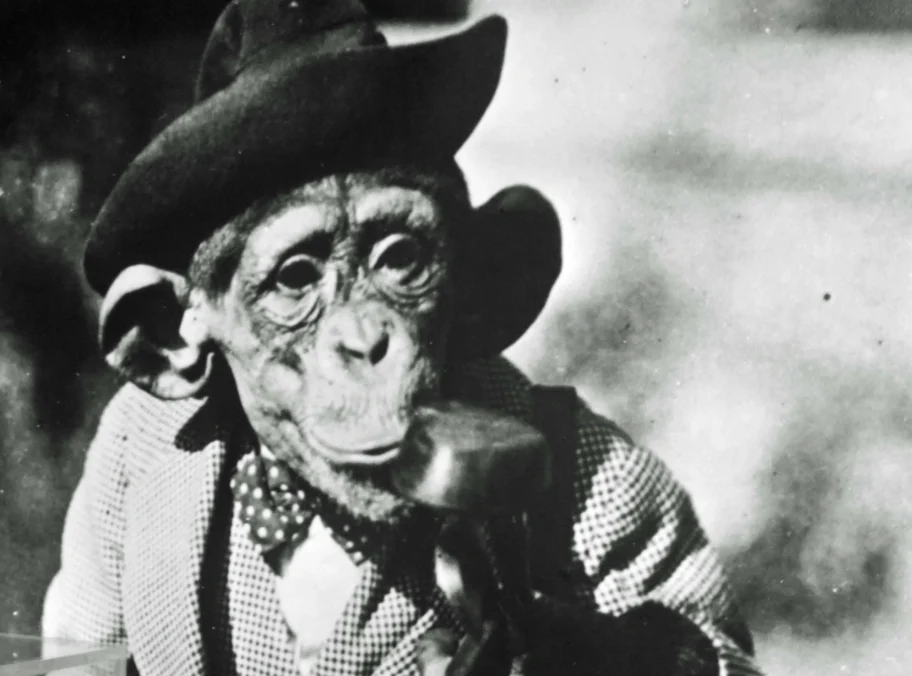

By the time the trial opened on July 10, Dayton was awash in visitors, including journalists, partisans on one side or the other, and chimpanzees. Banners advocated Bible-reading. Lemonade stands popped up. Nearly a thousand people crowded into the courtroom, and over Darrow’s objections, the Scopes trial opened with prayer.

The trial itself was not so much about Scopes himself or whether he had in fact taught evolution in violation of the Butler Act. As the proceedings unfolded, the trial became a proxy for larger issues. Bryan posited that “if evolution wins, Christianity goes,” and Darrow countered, “Scopes isn’t on trial; civilization is on trial.” He added that the prosecution was “opening the doors for a reign of bigotry equal to anything in the Middle Ages.”

The trial had its comic moments. When Darrow complained that the judge, John T. Raulston, invariably ruled for the prosecution, while “a bare suggestion of anything that is perfectly competent on our part should be immediately overruled,” Raulston asked Darrow, “I hope you do not mean to reflect upon the court?” Without missing a beat, Darrow replied, “Well, your honor has the right to hope.” The judge, who had attended Bryan’s sermon at the local Methodist church the previous Sunday, cited Darrow for contempt but dropped the charge when Darrow apologized.

Raulston refused to hear testimony from most of the defense witnesses, so on the seventh day of the trial, the defense called Bryan to testify as an expert on the Bible. Bryan agreed, with the stipulation that he in turn would be able to interrogate the defense attorneys. The New York Times described what ensued as “the most amazing court scene in Anglo-Saxon history.”

“You have given considerable study to the Bible, haven’t you, Mr. Bryan?” Darrow began. Bryan replied that he had studied the Bible for about fifty years. Darrow proceeded with a fusillade of village-atheist questions about Jonah and the whale, Noah and the great flood, Joshua making the sun stand still, and the creation stories in Genesis. Bryan, who had initially insisted that “everything in the Bible should be accepted as it is given there,” eventually conceded that the six days of Genesis in the first creation account might refer to “periods” rather than twenty-four-hour days.

The exchange grew testy. Two wizened heavyweights circled one another in the ring. At one point, Bryan said, “I do not think about things I don’t think about.” Darrow asked, “Do you think about the things you do think about?” Bryan replied sheepishly, “Well, sometimes.” Bryan complained that Darrow was trying to “slur at the Bible” and declared that he would continue to answer Darrow’s questions because “I want the world to know that this man, who does not believe in God, is trying to use a court in Tennessee”— but Darrow interrupted. “I object to your statement,” he thundered, and to “your fool ideas that no intelligent Christian on earth believes.”

The judge adjourned court for the day, and the next morning he ruled that the interrogation would not continue, and therefore Bryan would not have the opportunity to examine Darrow. Raulston also struck the exchange from the record.

Darrow asked, “Do you think about the things you do think about?” Bryan replied sheepishly, “Well, sometimes.”

The outcome of the Scopes trial was never in doubt, but Darrow had one more trick up his sleeve. He asked the jury to find the defendant, his client John Scopes, guilty, so that the verdict could be appealed to the Tennessee supreme court. That was the intention all along, but Tennessee law specified that if the defense asks for a guilty plea, the prosecution was not entitled to a summation. Bryan, who had been preparing his closing arguments for weeks, was silenced.

After nine minutes of deliberation, the jury of eleven white men, all but one of whom attended church regularly, returned a guilty verdict. Scopes was fined one hundred dollars. Bryan, a broken man, died in Dayton five days later.

Americans have been debating the meaning of the Scopes trial for a century now. The immediate judgment was that Bryan and the fundamentalists may have won their case in the Dayton courtroom, but they lost decisively in the larger courtroom of public opinion. Mencken, who ungenerously described the locals as “gaping primates from the upland valleys of the Cumberland Range,” offered his judgment on the proceedings on July 18, 1925, even before the conclusion of the trial. “Let no one mistake it for comedy, farcical though it may be in all its details,” he wrote. “It serves notice on the country that Neanderthal man is organizing in these forlorn backwaters of the land, led by a fanatic, rid of sense, and devoid of conscience.”

Chastened and publicly humiliated, evangelicals hastened their withdrawal from the broader society, which they regarded as both corrupt and corrupting. The Scopes trial wasn’t wholly responsible for their turning inward—the prim orderliness of Victorian America was giving way to the Jazz Age and the flapper era, after all, and “modernism” was infecting mainline Protestantism—but the events in Dayton removed any lingering doubts whether evangelicals could coexist comfortably in a multicultural society.

Beginning in the 1920s, then, evangelicals set about the task of constructing their subculture—a vast and interlocking network of congregations, denominations, publishing houses, missionary societies, Bible camps, media, Bible institutes, colleges, and seminaries. The evangelical subculture became a fortress, a place of refuge to protect themselves and especially their children from the corrosive effects of the broader culture.

While evangelicals hunkered into the subculture of their own making, their erstwhile adversaries piled on. Stewart G. Cole’s The History of Fundamentalism, published in 1931, described one of the movement’s organizations, the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association, as a “cult” led by “disturbed men.” Norman F. Furniss, author of The Fundamentalist Controversy, 1918-1931, correctly identified the militarism at the heart of fundamentalism, which he attributed to “ignorance, even illiteracy.”

Most liberals, theological and political, believed that science and common sense had prevailed once and for all in that steamy Tennessee courtroom, that Darrow had banished the retrograde “fool ideas” of evangelicals, especially fundamentalists, to the margins. But was that true?

Although it was never enforced, the Butler Act remained on the books in Tennessee until 1967. Publishers, afraid of backlash from evangelicals, quietly expunged evolution from their textbooks. Many states continued to prohibit the teaching of evolution in public schools, which led in turn to an alarming decline in science education, a deficit that finally came to public notice when the Soviets launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957. John F. Kennedy’s aspirations to land a man on the moon jumpstarted science education, which rested on the fundamentals of Darwin’s evolutionary theory.

But many evangelicals, still hunkered defensively in their subculture, remained wary. In the 1960s and 1970s, several organizations emerged, like the Creation Research Society, the Bible Science Association, and the Institute for Creation Research, that advocated “creationism” and later, “scientific creationism,” a sometimes-comic attempt to clothe biblical literalism with scientific legitimacy. Most scientists scoffed at the science behind “scientific creationism,” dismissing as preposterous creationist claims that the Grand Canyon, for example, was formed in a matter of weeks.

Courts repeatedly refused to countenance creationism as anything but religious, and therefore impermissible in public schools. Undeterred, the religious right set about inventing new guises for creationism, which led to something called “intelligent design,” the notion that creation is so ordered and complex that an intelligent designer must perforce have initiated and superintended the process.

The major legal showdown for intelligent design—a kind of latter-day Scopes trial—took place in 2005 in Dover, Penn., where the school board required biology teachers to read a statement asserting that Darwinism “is not a fact” and urging students “to keep an open mind.” U.S. district judge John E. Jones ruled on Dec. 20, 2005, that intelligent design was “a mere re-labeling of creationism and not a scientific theory”; requiring that it be taught in public schools thus represented a violation of the establishment clause.

Even now, as creationists are very likely working on the next evolutionary iteration of creationism, the religious right continues the attacks on science and public education that animated the Scopes trial a century ago. Although it would be logical for those espousing creationism to evince concern about climate change and the environment, those sensibilities have yet to emerge on any meaningful scale. Evangelicals have identified public education, one of the cornerstones of democracy, as an enemy, and have supported efforts to shut down the Department of Education and use taxpayer funds to provide vouchers for religious schools. The Supreme Court, with scant regard for the First Amendment, is abetting those efforts.

The Scopes trial cast a long shadow over American life. The jury may have taken only nine minutes to determine the fate of John Thomas Scopes, but the issues at stake in Dayton are still contested today.