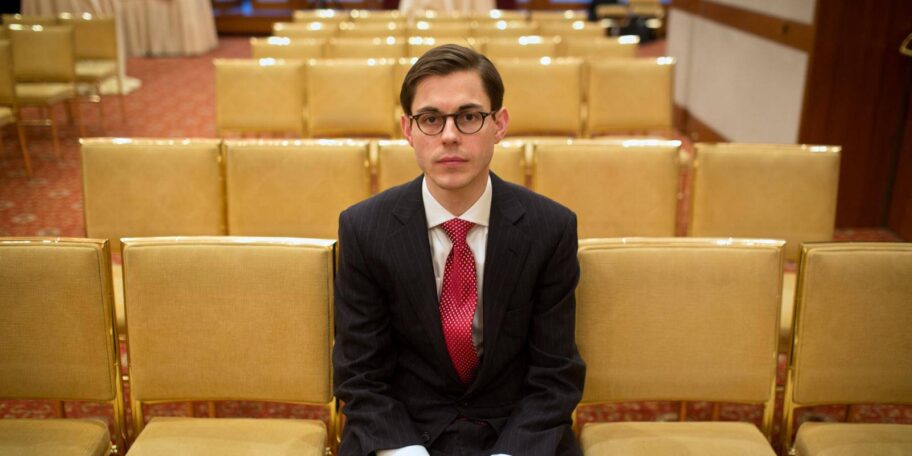

Julius Krein is the founder of American Affairs, a journal that since its debut in 2017 has envisioned, largely through wonkish, graph-heavy articles on the arcana of industrial policy, what the possibilities might be for a rational version of economic nationalism. Trump’s re-election and omnidirectional tariff campaign have made such thinking both more urgent and more difficult. I have been a semi-frequent contributor to American Affairs since 2021, in a series of essays trying to articulate what I thought could be the conditions for a revitalization of political liberalism (against illiberal foes from the right and left) and state-led economic planning (against the bewildering immiserations of contemporary capitalism). Those causes strike me, at the present moment, about as promising as the revival of Sumerian.

When I first began writing for American Affairs, I wondered, with some concern, about the role of political Christianity in its editorial line-up. Gladden Pappin, the deputy editor, is a post-liberal Catholic with links to Hungary’s Orban government, and a past as a socially conservative undergraduate “gadfly” homophobe at Harvard. In practice, however, American Affairs has had little to say about social or theological issues, while the practical economic problems it usually addresses, such as supply-chain logistics and patent law, seem to offer little space for religious debate. Christians today may have various economic views, from vague enjoinders to care for the poor to “distributionist” schemes dusted off from a hundred years ago, but my co-religionists seem scarcely able to mobilize such ideas in actual discussions of political economy. This is surely a loss for, and reflects the decline of, Christianity as an intellectual tradition by which believers can orient their action in the world.

I soon stopped thinking about whether American Affairs was in some way a “Christian” journal, and, if so, whether it was my kind of Christian. Until, that is, I read an essay in its pages by Krein last summer on the apparently non-religious topic “Statesmanship and Political Philosophy.” It’s a collective review of several books that in some way deal with leadership—a concept expansive enough to include a volume (originally a Ph.D. dissertation at Yale) by former Straussian academic and now internet personality Costin Alamariu (better known as Bronze Age Pervert), which I’ve also written about. I was impressed by Krein’s critique of Alamariu’s warmed-over Nietzschean summons to elites to throw off the moral restraints of our post-Christian culture. Implicitly, Krein was arguing that mainline Christianity had played a critical, often positive role in shaping America’s political and intellectual elite during the era when our country emerged as a global power, and that the secularization of that elite over the past half-century has had a number of alarming consequences.

In subsequent conversations with Krein about the implications of his essay, I realized that he, like me, is a convert to Anglo-Catholicism, a tendency within the Episcopal Church (and within such splinter denominations as the Anglican Church of North America) informed by the liturgical and theological traditions of the Roman Catholic Church. While sometimes seen as an import to the United States from the nineteenth-century Oxford movement in the Church of England, Anglo-Catholicism has a distinct American origin and history. Today it is concentrated in a small number of parishes, and seminaries such as Nashotah House.

Having found ourselves within the concentric circles of Anglo-Catholicism, Episcopalianism, mainline Protestantism, and American Christianity, I asked Krein if he would elaborate on his thinking about religion and politics—and what our particular traditions might have to offer a divided and disoriented country—in the following interview.

Blake Smith: Hi, Julius. Could you start by sharing a bit about your religious background, where you are now and what led you there?

Julius Krein: The religious environment I grew up in seems highly unusual in retrospect. I am from a small town in South Dakota, and growing up in the 1990s I went to an ELCA [Evangelical Lutheran Church in America] Lutheran church. If for no other reason than sheer distance from the metropole, that church was probably about thirty or forty years behind the developments occurring elsewhere in the mainline at the time. So doctrinally and liturgically, it was quite conservative, but not as a result of some conscious evangelical or “trad” reaction to progressive movements; it simply hadn’t been affected by them. In my town, Christianity was so normalized that it was not politicized. People were obviously aware of the culture wars in national politics, but they had no effect on everyday life. No one cared if the public school put on a Christmas concert rather than a holiday concert; it would have been silly to do anything else, much less to argue about it. In that milieu, an ACLU-style atheist as well as a Bible-thumping southern evangelical politician—had there been any around—would both have been seen as antisocial cranks.

When I moved to the East Coast for college, the religious life I encountered was, let’s just say, very different. I eventually gravitated toward Anglo-Catholic Episcopal churches. As strange as it may sound—and I don’t mean this quite literally—Anglo-Catholic parishes in New York and Boston offered the closest liturgical and musical experiences to the church I grew up in. And in the course of this process I concluded that these experiences were quite essential. Politicized sermons are easy to ignore, and you can find all varieties of theological content and debates on the internet. But the experiential elements of communal observance and worship were of much greater importance than I had previously realized.

BS: We’re both Episcopalian and Anglo-Catholic, which I admit I find slightly embarrassing as a point of religious identification, since it sounds like I sit around reading Dorothy Sayers and drinking port. One of the things that I like—but also find confusing—about this tradition, particularly coming to it from a childhood in another denominational tradition (Southern Baptist), is that it can be categorized so many ways. I’d say that I’m a Protestant, but I attend a parish where the clerical line is “we acknowledge [regretfully] that the Reformation happened,” and no one ever wants to sing “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” Insofar as Episcopalianism is Protestant, though, it’s one of the mainline denominations that once—particularly in mid-twemtiethth-century—controlled what we could call the commanding heights of American religiosity. I’d like to ask how you see, first, the role of mainline Protestantism in shaping a certain historical ethos among American elites, and what the decline of the mainline denominations means for our culture?

JK: I have had a different experience. Because it would seem so easy for Anglo-Catholics to go all the way to Roman Catholicism, and yet they don’t, they must in some ways be highly committed Protestants. At some level, Anglo-Catholics must actively interrogate what binds them to Protestantism and what is important about this tradition, especially now that the political and narrowly theological issues surrounding the Reformation are no longer relevant.

My answer to this question is more philosophical and intellectual. Summarizing briefly, with all the crudeness that entails, I find that the Catholic intellectual tradition tends to emphasize the affinities between reason and revelation, the rational and irrational, the city of man and the Kingdom of God, whereas Protestantism is more attuned to the conflicts between them. In terms of intellectual history, one could schematize it as Aristotle and Aquinas versus Plato and Augustine. In my view, the latter approach, the Protestant approach, is the truer one. And although I just said that there is more to Christian observance than theological and intellectual matters, I nevertheless think that this Protestant orientation is vital and worth maintaining.

As for the decline of mainline Protestantism, the French writer Emmanuel Todd recently offered a more bracing account than anything I have read by an American author. Todd sees it as nothing less than a civilizational collapse, and argues that it’s not coincidental that the decline of the mainline coincides with the rise of neoliberal atomization across society. For both elite and people, it becomes impossible to imagine a collective future. Likewise, the shared norms that once put bounds on worldly political and economic competition seem to disappear, which is something E. Digby Baltzell discussed as well.

Nevertheless, it seems to me that the postwar mainline was itself more fragile and more contested than we have come to think of it, as its rapid decline would suggest. Already in the 1940s and ’50s, observers began to describe the “cut-flower culture” of American religious life. When I look at the most celebrated theologians of that era, I see mainly figures who were translating secular academic currents into a religious vocabulary. Aside from that, the mainline church by this point seems to have become little more than a therapeutic enterprise. This evolution is understandable in the aftermath of two world wars, but if the only message is “be nice to each other,” it turns out you don’t really need—and may not even want—Christianity for that. It is not surprising, then, that many people eventually decided to leave the mainline entirely. Christianity no longer possessed its own intellectual force that required serious confrontation by anyone outside it or perhaps even within it.

The term “adversary culture” is typically employed by conservatives to describe the progressive currents of the 1960s, and I think it accurately describes the left-wing movements within the church at this time. Yet, as you have suggested in your writing, the rise of right-wing evangelicalism could also be seen as a form of “antinomian opposition.” The result is that we are still stuck with two competing adversary cultures rebelling against what is now a vacuum left by the decline of the mainline. One attraction of adversary cultures is that they don’t feel the need to take responsibility for anything, or undertake an autonomous, constructive project, since they define their task solely in terms of opposition. This problem only seems to worsen with time, even as the initial objects of rebellion fade further into the past, both within and beyond Christian institutions.

BS: If we think about the Episcopal Church through its Anglo-Catholic tradition things could look quite different. Rather than being part of the vanishing center of the American elite’s religious life, Episcopalianism can look like a rather marginal, kooky, somewhat reactionary phenomenon. Which is how it did indeed look to many Americans after the Revolutionary War, when the denomination was tainted by association with the British monarchy, and in the early nineteenth century, when leading “high churchmen,” like John Henry Hobart, who was bishop of New York from 1816 to 1830, were scandalizing public opinion by condemning other denominations for not having apostolic succession. And of course the most famous American Anglo-Catholic, T.S. Eliot, remains an inescapable but troubling figure, not least because he seemed so desperate not to be American. What do you make of the Anglo-Catholic tradition in our country—does it have something to say to us in our political life?

JK: I think Anglo-Catholicism’s alienness from mainstream American (religious) culture is a great strength, at least in the present moment. Visible differentiation from the norm is an asset when the status quo is failing.

I also think that we have entered a “post-literate” era. We might very well lament this state of affairs, but it seems impossible to stop. In such circumstances, greater emphasis on non-textual elements of worship—which I think anyone will admit is a strong point of Anglo-Catholicism—seems more likely to be successful in finding a broader audience. The methods adopted to minister to illiterate peasants in the Middle Ages will probably become very useful once again.

Having praised Protestantism in the previous response, I would also like to give the Catholic part of the Anglo-Catholic tradition its due. Austere versions of Protestantism have been easily overwhelmed by secular currents throughout history: it is a remarkably short trip from Puritanism to Unitarianism to the Social Gospel to secular progressivism. A healthy appreciation for the outward elements of religious experience seems necessary to maintain the intellectual and spiritual content.

Finally, while there is probably too much scholarship on English matters in most fields at this point, the Anglican religious tradition seems astonishingly underappreciated today. This is a tradition that is naturally associated with Whiggish liberalism yet also began in rather authoritarian circumstances under Henry VIII. Its formation drew on deeper theological underpinnings but was proximately motivated by realpolitik and early strains of nationalism. The theological aspects of England’s efforts to navigate various religious fanaticisms throughout early modernity are distinctive and could offer lessons for dealing with the fanaticisms of our own time.

BS: Following up on that last question, we’ve seen in recent years a revival of Catholic political thought in America, perhaps most obviously on the post-liberal right, but also with the (perhaps temporary) re-expression of an earlier Catholic social(ist) movement. There are some echoes of this in Anglo-Catholicism, I suppose. On the right, the breakaway Anglican church was not only brought to schism over political issues (the place of women and gays in the church) but also, in venues like The Anglican Way magazine, there is the fostering of some political thinking. On the left, there are things like Earth and Altar or The Hour. Do you see Anglo-Catholicism, or the Episcopal church more broadly, having a role in the conversations with American Catholic political thought? You have, after all, via American Affairs, some connections to Catholic post-liberalism.

JK: Several years ago, I planned to coauthor a piece with a leading Catholic “integralist” that we never found time to write, titled “Ecumenical Integralism.” The basic argument was that, until very recently, religious institutions, in their interactions with politics and across sectarian lines, tended to emphasize the liberal elements of each tradition; going forward, however, such conversations would coalesce around the non-liberal or postliberal elements.

Within Christianity, for example, Catholics focused on natural law as a supplement to liberalism. “New Natural Law” would supposedly provide the missing foundations for American constitutionalism, or something like that, at least for a certain right-of-center philanthropic complex. Meanwhile, Protestantism continued to emphasize individualism, freedom of conscience, and so on. (Similar trends can be noted outside of Christianity, too.)

Going forward, however—my coauthor and I planned to argue—the locus of any substantive religious dialogue would shift toward non-liberal themes. For a vanguard of elite Catholics, there has been a rediscovery of older teachings on, inter alia, the relationship between church and state and the economics of Rerum Novarum. Protestants, meanwhile, might reemphasize faith and vocation over individualism. It should not be forgotten that Protestantism did not arise as a project of “religious liberty” but initially had the effect of reuniting church and state, a sort of integralism from the other direction. Within Calvinism, Calvin’s Geneva, Cromwell’s England, and Puritan Massachusetts could be described as integralist societies par excellence.

The point is not that Christian theocracy is possible or desirable today—though contemporary progressivism arguably displays certain theocratic tendencies—but rather that fundamental questions seemingly settled by modern liberalism have now become unsettled. Liberalism itself has been reduced to its own moralism, rather than a structure that allows for people with competing moral commitments to constructively interact through political institutions. In this context, Anglo-Catholicism’s “royalist” trappings might generate some unexpected insights.

The self-proclaimed Nietzscheans today (as in the past) seem much more concerned with podcasting and blogging and literary criticism than with acquiring or exercising power.

BS: I’d like to shift focus to your essay “Statesmanship and Political Philosophy,” which I think makes some really important points about what Christianity, in its ethical, cultural, and political effects, does or can do, and how it gets misunderstood by both critics and apologists of the wrong kind. You make a point that’s worth quoting at length:

Christianity ought not to be seen simply as a leveling, universalizing, pacifying, or life-denying force in Western intellectual and political history. (Of course, none of these tendencies are unique or original to Christianity.) On the contrary, by allowing for distance between the cities of God and man, Christianity provided a means to negotiate conflicting desires for domination and recognition, expanding the horizons of political ambition. Energies that would otherwise have been endlessly expended on the vagaries of tribal politics—oscillations between the most mindless clan moralism and the pettiest self-interest—could at least occasionally be directed toward grander ambitions . . . .

There’s a lot to unpack here. Could you say more about how Christianity helps, or rather helped, us negotiate the conflict between the desire for domination and the desire for recognition? This is, in contemporary American political theory, a central theme of Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man. Fukuyama argued, with what now seems like tragic irony, that liberal democracy succeeds in reconciling them through the capitalist marketplace … exemplified, he said, by the non-political life of businessman/showman Donald Trump.

JK: This notion of a conflict between the desire for domination and the desire for recognition is drawn from Hegel, whom Fukuyama is channeling through the interpretations of Alexandre Kojève and Allan Bloom. Hegel, significantly, always professed to be an orthodox Lutheran!

In both the liberal and “Straussian” schools of political philosophy, Christianity, even more than other religions, is typically seen as nothing more than historical baggage or a waystation on the path to secular liberalism, for good or ill. And that is, not surprisingly, how Fukuyama treats it—merely as a precursor to “liberal democracy”—and he reads Hegel as doing the same. For virtually any prominent Western intellectual today, Christianity is not something that needs to be understood in its own right; it only matters as a historical artifact. This incuriosity leaves a lot of blind spots.

Ignoring the rather deep water under the bridge between the advent of Christ and late-twentieth-century liberal democracy, these simplistic intellectual histories narrow Christian political thought and practice into an extremely narrow caricature. Fukuyama, for instance, describes Christianity’s contribution to Western political history almost entirely in terms of its teachings of “moral equality” among human beings. But how that theological concept should translate into worldly political arrangements seemed far from obvious for most Christians throughout history. And even if you want to argue that such a notion of moral equality inevitably leads to something like American democracy circa 1989, what part of this genealogy is distinctively Christian? After all, one can find various commitments to egalitarianism and universalism in other religions, as well as in philosophical doctrines that predated Christianity, such as Epicureanism and Stoicism, though they are a long way from Christianity in other respects.

The same potted histories appear in the right’s increasingly frequent attacks on Christianity for being too egalitarian, even as the left still sees it as a reactionary force. Returning to the terminology of domination and recognition, both Fukuyama-style liberals as well as their “Nietzschean” critics tend to approach Hegel’s “master-slave dialectic” in much the same way. The argument, in short, is that “liberal democracy” has solved the problems of domination and recognition (along with the amelioration of material conditions) for the “slaves,” but would-be “masters” could (or should) rebel against its leveling constraints. The divide between these camps is whether one celebrates this “aristocratic radicalism” or not. I wrote the essay you cited in part to explore what these caricatures obscure about Christianity and its relationship to fundamental political themes like tyranny and statesmanship.

If one views Christianity merely as a precursor to the liberal democracy of the last man, then it can seem that we are in the midst of some Nietzschean rebellion against Christian morality, a narrative which is in many ways flattering to both sides. But I don’t think that this is what is happening, or that a truly Nietzschean political movement is even possible. After all, the self-proclaimed Nietzscheans today (as in the past) seem much more concerned with podcasting and blogging and literary criticism than with acquiring or exercising power. And the people who do wield power—including right-wing movements in the West—continue to emphasize victimhood and democracy as sources of legitimacy.

It is worth recalling that, in Hegel’s original formulation of the master-slave dialectic, it is not only the slave who is dissatisfied with the master’s domination; the master in his own way is dependent upon the slave and cannot achieve genuine recognition, either. This side of the problem—the master’s unsatisfied need for recognition—is largely ignored by all sides today. (Perhaps the ultimate expression of slave morality is the belief that the master is motivated mainly by the desire to exploit the slave.)

The ancient philosophers discussed this problem as well, although in different terms: being a tyrant, or simply a ruler, is not especially pleasant. The political life, even if focused entirely on personal aggrandizement, is quite difficult. Anyone who embarks on it solely to maximize pleasure or satisfy personal desires quickly discovers that it’s not worth the effort. This is no less true today, and so I do not think that politics culminates in the choice between last-man liberalism and Nietzschean tyranny. Political theories of hedonistic self-assertion are not enough to sustain an individual political life, much less motivate collective action. Such narratives end up celebrating the aesthetic value of decadence more than the discipline and virtue of warrior-aristocrats.

Thus, what we see among elites today is not the revival of any recognizable aristocracy, or even a pale imitation of the American WASP elite of a few generations ago, but instead either Epicurean withdrawal from political responsibility or increasingly desperate attempts to win political recognition. Trump might be one instance of this but is hardly the only one: Elon Musk is another, perhaps even more obvious example, along with the legions of billionaire philanthropists subsidizing all manner of bizarre political causes and starting new careers as pundits and podcasters. And as I tried to show in the essay, this (frustrated) desire for recognition is not just theoretically but also practically in conflict with effective statecraft, even if one defines the latter solely in terms of power and domination.

To me, this is the real story of the end of the end of history. It’s not that liberal democracy was too effective or “too good” and provoked a thumotic rebellion of the great. On the contrary, the seeming triumph, the seeming appearance of an “end of history,” provoked an internal crisis among American elites, just as the Hegelian master winning the initial battle to become master is the root of his frustration. And so, almost immediately, the apparent triumph of “liberal democracy” is accompanied by confusion about what this means and paranoia about its future—Fukuyama’s book itself representing a prime example—which only deepens as time goes on. From the beginning, American elites could not simply content themselves with a geopolitical victory. It was not enough to have power and maintain it. This victory had to be a moral victory, a spiritual victory, and American elites were desperate to believe that not only must/would the entire world adopt these values, but former enemies will do so voluntarily—and they would like it! Hence China would have to liberalize and democratize. Hence 9/11 was such a shock and provoked such a self-defeating response. Hence Russia’s evolution away from democracy continues to loom so large. America’s leadership class needed to believe that they would achieve not just coercive power but recognition. But the efforts of American elites to achieve recognition became increasingly deranged and counterproductive.

And although it’s impossible to make a causal claim, I don’t think it’s entirely a coincidence that this process occurred among generations increasingly disconnected from Christianity, especially “mainline” or “establishment” Christianity. In explicitly separating earthly and spiritual kingdoms, Christianity uniquely allows for a realm of recognition among spiritual equals without requiring the complete denial or rejection of worldly political realities. It is very difficult for a purely secularized conception of “democracy” or even “citizenship” to provide this. That is not to say that Christianity automatically ensures competent government, obviously, or that non-Christian societies cannot have capable rulers. But I do think Christianity provides a special intellectual context that allows for the formulation of basic concepts like “statesmanship.” (And there’s a reason why those elements of classical political philosophy that push in this direction, such as the Platonic and Aristotelian traditions, are often seen as proto-Christian and were readily incorporated by Christian theologians.) So as the American political class became less Christian, it actually became less capable of realpolitik.

In other words, my contrarian conclusion is that the political significance of Christianity is more about the “masters” than the “slaves.” Perhaps Christian religion also provides comfort to the oppressed, but many frameworks, both religious and secular, can do the same. Outside of Christianity, however, it is more difficult to address elites’ own alienation or channel their desire for recognition in productive directions.

It is worth recalling that, in Hegel’s original formulation of the master-slave dialectic, it is not only the slave who is dissatisfied with the master’s domination; the master in his own way is dependent upon the slave and cannot achieve genuine recognition, either.

BS: How does Christianity help us mediate, as you suggest, between the worst sort of collectivism and the worst sort of individualism? Or perhaps mediate is the wrong word, since these two “worsts” do so often go together! Let’s say, transcend?

JK: I don’t think it’s anything more complicated than Christianity’s consciousness of the division between the City of God and the City of Man, “render unto Caesar,” and so on. But this distinguishes Christianity from the other monotheistic religions as well as ancient paganism and, I would argue, “rational” philosophy. This distance allows for another dimension or perspective from which to approach the relationship between the individual and the collective.

Collectivism and individualism are not simply opposites, so the worst forms of each do tend to go together. Or perhaps that makes more sense when put in terms of fanaticism and nihilism, or moralism and selfishness. These apparent extremes are never far apart.

On this point, I think the postmodernists were right in the sense that it’s not hard to trace how any given moral doctrine or epistemic system serves to cloak some “exploitative” power dynamic. But the left-wing postmodernists were guilty of their own moralism insofar as they thought that pointing this out would be “emancipatory,” or that emancipation would always be good. It might, in fact, be debilitating, or it may simply usher in an even more totalitarian moralism.

Whereas the ancients spoke of a “cycle of regimes,” our post-postmodern disorientation seems to foreclose any pathway out of decline. For the most ambitious and intelligent people today, the ultimate lesson imparted by their education is that the moral doctrines underpinning our society are false and self-serving. Importantly—in both left and right versions of this narrative (and there is a right-wing version, as discussed in my essay)—only two responses are offered: material and intellectual withdrawal, or the cynical manipulation of public morality to get want you want. The available modes of political engagement, in other words, are not “exit, voice, and loyalty,” but exit and exploitation. Both responses lead to the same result, however: the embrittlement and decline of political order. Neither recognizes a “whole” or “common good” that is worthy of loyalty, despite its imperfections; again, all that remains are competing adversarial cultures.

Christianity opens other avenues for engagement. Because it is possible to accept that the fallibility of man does not contradict the perfection of God, one can recognize the limitations and imperfections of any political order without necessitating a retreat entirely into irrational subjectivity (and tribalism) or self-serving irony. Likewise, the inability of human reason to access a perfect or absolute truth does not make human life, including political life, irredeemable. After all, claims that “God is dead” should not be particularly troubling to Christians.

BS: I find very productive the idea you sketch of Christianity as being not a holistic, all-encompassing worldview, but as opening up a generative “distance” between polarities of desire, or among the different roles that we inhabit in the course of our lives (spiritual and temporal). I don’t know if you’re familiar with Ian Hunter’s work on the early modern Protestant German legal theorists Samuel von Pufendorf and Christian Thomasius, but he brilliantly recovers the idea that quite sincere Christians, amid the religious wars of the seventeenth-century, tried to restrain both the power of the clergy and the fanaticism of the crowds by making the state “absolute,” i.e., above and indifferent to religious claims, and by articulating a vision of human life as divided among role-based personae, each with a distinct ethos (this is a clear anticipation of Max Weber). This to me seems much more promising and robust than the idea, held by many liberals, that our religious commitments—and other intense desires—can be held in a “private” domain of mere opinion, which we withhold from trying to actualize in society out of some spirit of ironically tolerant self-restraint. Can you say more about the resources of distanciation (or however we might put it), this creation of a prudential sense that there are multiple, competing goods, that you see Christianity as offering (and many Christians as currently neglecting)?

JK: I am not familiar with Ian Hunter’s work, but your summary sounds promising. And it does seem that once liberal neutrality comes to be seen as merely ironic—even if everyone continues to see such institutional neutrality as instrumentally desirable—then classical liberal politics is no longer sustainable. This is often described as the depletion of “preliberal capital”—of some shared moral or metaphysical horizon within which liberal toleration can occur—but it may be more precise to regard it as the loss of a peculiarly Christian orientation that balances competing goods in a fallen world. And if the latter is the case, then perhaps it is possible to achieve some kind of prudential politics without requiring ironic attachment to liberal fictions.

Much of what we have been discussing relates to the “reason of state” tradition, which has fallen out of fashion both as a topic of study and as a guide to practical politics, but is perhaps the best name for the Christian “distanciation” or “balancing” of competing goods. It is arguably simpler and more emotionally satisfying to think in terms of some historical evolution toward liberalism, which is perhaps why that framing appears to have won out until recently. But such narratives are difficult to take seriously anymore.

Reason of state should not be simply reduced to cynical maneuvering or realpolitik. The most astute critics of this tradition recognized the complex relationship between Christian self-denial and power politics. Aldous Huxley’s 1940 book Grey Eminence, for example, is a stylized biography of François Leclerc du Tremblay, or Father Joseph, Cardinal Richelieu’s principal aide during the Thirty Years’ War. Huxley sets out to trace how a sincere and devoted Christian mystic like Father Joseph could be the architect and agent of so many devious and often cruel schemes to both centralize French state power as well as to strengthen France’s international position. Huxley is a harsh critic, and longs for some kind of Buddhist or Epicurean ataraxia, but his critique is in my view more appreciative of Christianity than many of today’s apologias.

Both the priest and the hangman can be instruments of God’s will. The temptation—for both sides—lies in conflating these roles. Martin Luther, in criticizing the politics of his own time, wrote that “souls are ruled by steel, bodies by letters. So worldly princes rule spiritually, and spiritual princes rule in a worldly manner.” It’s not hard to see a similar confusion of the spiritual and material today. And while one can interpret Luther’s critique as a sort of proto-liberalism, it fundamentally relies upon a Christian framework which embraces the distinction between the cities of God and man, and dignifies the different roles that we inhabit in the course of human life. A purely secular liberalism ends up in the same place as religious fanaticism: it cannot sustain “the state” or “statesmanship”; politics merely oscillates between mindless tribalism and mercenary moralism.

One can recognize the limitations and imperfections of any political order without necessitating a retreat entirely into irrational subjectivity (and tribalism) or self-serving irony.

BS: You seem to propose that it’s really Christianity, and not secular liberalism or the stance of the Straussian philosopher looking down on “the city of man,” that provides cultural resources by which we can manage to be both sincerely and seriously engaged in our moral commitments and able to restrain those commitments in ways that allow us not only to live with others, but engage in far-sighted collective projects with them. To the extent that this combination of moderation and concern for the future seems critical to statesmanship (and in conflict with religious fanaticism, in its demands for immediate and total realization of the Good) then it would make sense that, if you’re right, Christianity has an important contribution to make to the formation of political leaders—or even to the ordinary good political sense that needs to be widespread for a democracy to function democratically. But in the essay you’re also quite pessimistic about actually existing American Christianity fulfilling this function … or rather, since Christianity doesn’t exist for the sake of good political order but rather perhaps the other way around, it might be better to ask: what is wrong with American Christianity such that it doesn’t bear these fruits?

JK: A few years ago I saw a (low-production-value) documentary about an escaped convict who evaded capture for several years by disguising himself as a Catholic priest (among other things). In an interview about how he managed to maintain this act for so long, he said that even though he had very limited knowledge of the Bible or the Catechism, no one really cared as long as he focused on positive messages: love, forgiveness, and so on. The whole thing was rather heavy-handed; I couldn’t make it up.

American Christianity has been taken for granted for a long time, and it has taken its status for granted for a long time. The foundations have eroded considerably, and most Christian institutions took their present shape within a very different social context. I think a great deal of introspection, maybe even a sort of “reformation,” is in order. Thus, I don’t think that churches need to become more politicized or partisan, at least not in any conventional sense, which I suspect would only heighten the internal confusion.

Instead, Christians need to recover an understanding of Christianity on its own terms. As the phrasing of your questions suggests, Christianity defines ends; it is not merely a means to some other end. Christianity is not simply a particular expression of “liberal democracy,” or a historical waystation on the path to it. It is not a set of therapeutic exercises or a generic exhortation to “be nice.” It is not merely a tradition, an “identity group,” or a vote bank. Christianity is more than a “philosophy,” but it does have distinctive things to say about the relationship between the universal and the particular, the spiritual and the physical, the temporal and the eternal, and the individual and the community. If Christianity is to be a living faith, Christians must begin approaching these issues directly once again, rather than allowing their religion to be defined entirely by its secularized derivatives.

Finally, rather than think only in modern terms of “church and state” or “religion and politics,” we should remember the ancient perspective, in which the order and disorder of the political community reflect the order and disorder of the individual souls within it. In both our politics and in individual lives, the absence of Christianity is increasingly felt. To me, then, the question is not whether Christianity becomes more or less “political,” but whether it can once again define its own ends.