Adam Valen Levinson yearned to learn Arabic. He did and wrote about it in The Abu Dhabi Bar Mitzvah: Fear and Love in the Modern Middle East. His publisher, W.W. Norton, successfully placed an excerpt in Literary Hub, the website widely known as LitHub. The excerpt ran on Dec. 7, 2017. It begins with Levinson—who died last November, seemingly a suicide— describing how he wanted to learn Arabic after the 9/11 terrorist attack, which was perpetrated by fundamentalists tied to the extremist group Al Qaeda.

“By learning the primary language of this region, some of us thought, we might be able to figure out what they were really thinking,” Levinson wrote. “Learning to spell salaam alaykum seemed like a good place to start.”

Apparently, it wasn’t.

Four days later, LitHub apologized for running the excerpt. In their “Apology from the Editors,” which was appended to the excerpt, LitHub editors Jonny Diamond and Emily Firetog wrote: “The exoticizing language in any piece like this, the casual Othering, is not only a failure of literary empathy and observation, but it reinforces a toxic framework within which racism flourishes and power retrenches. As we have said before, there can be no meaningful separation of the literary and the political.”

LitHub turned ten years old this year, and it’s a central—if not the central—organ of publishing news, discussion, and PG-rated gossip (i.e., nothing about what transpires at boozy publishing parties). “That we’re the most popular editorial book site in the world, after Amazon’s Goodreads, is frankly bonkers,” Diamond wrote in an anniversary note (the claim is apparently based on figures from SimilarWeb, which counts page views).

The site’s evolution, and its increasingly prominent commitment to literary politics, is a case study that can help us understand the state of the publishing industry today. Publishing is dying and transforming at the same time, looking for new readers—even as fewer Americans than ever are cracking open a book (an astonishing 40-percent drop in how many Americans read for pleasure since 2003, according to new polls). Long dominated by white women, the book world has been desperate to diversify, even as it continues to shed jobs amidst slumping sales and consolidations. The rise of artificial intelligence doesn’t exactly help.

But in becoming more overtly political, LitHub has also alienated some readers and writers, turned off by its increasingly leftward slant, which sits uneasily next to traditional literary content. That lean has become especially pronounced since the Hamas attacks of October 7, 2023, leading the writer Lisa Smith Siegel to call its newsletter “a daily delivery of anti-semitism in your email box.” On topics such as free speech and gender politics (including, inevitably, l’affaire Rowling), LitHub has embraced positions well to the left of the mainstream—though arguably not so far to the left of the industry it covers. You can still find LitHub posts about how Substack is a font of right-wing propaganda, the kind of Biden-era stance that most outlets, and writers, have dialed (or walked) back in the current moment, for better or worse.

If the cancellation of Jimmy Kimmel is a reminder that the Trumpian culture reckoning has gone too far, the persistent leftism of LitHub is a reminder that there are places—at least one being a quirky site about those relics known as books—that are holding fast against it.

In the last two years, LitHub has given consistently positive coverage to anti-Israel artists, and to efforts to stigmatize writers or organizations they deem insufficiently critical of Israel. And while cultural boycotts are a controversial stance in a discipline (that is, literature) historically interested in bridging cultural and national divides, LitHub has tended to portray them positively, at least when it comes to Israel. “Shame on you, Lithub,” a commenter wrote in response to a post last year that seemingly encouraged an open letter by authors refusing to work with Israeli institutions. “This will do nothing to help innocent Palestinian people,” they wrote. “It will create more hostility toward the Jewish people, however.”

There is perhaps nothing surprising about a publishing tip sheet taking a strong editorial position on Israel, given the leanings of its readership. But such a publication could still fulfill its news-gathering mission. It is, therefore, just as telling to inspect what LitHub does not cover.

For example, in August, The Free Press revealed that Thomas Gebremedhin, a senior executive at Doubleday, had shared an Instagram post celebrating the murder of Wesley LePatner, a Manhattan finance executive, in a mass shooting. She had not been the target of the deranged gunman, but because LePatner was a proud supporter of Israel, she attracted the ugly ire of the online far left.

The meme that Gebremedhin shared advised her to “rest in piss.” There was a predictable firestorm in the right-wing ecosystem, but also legitimate questions about Gebremedhin’s judgement. Those questions, it turns out, were not confined to social media. “We can confirm that Thomas Gebremedhin has been placed on leave until October 1,” a Penguin Random House spokesperson told me.

His suspension had previously not been reported—but would have easily been discoverable by the premier literary news sites in the nation. Literary politics aside, one would think that a controversy surrounding a publishing executive would merit coverage by LitHub, for which Gebremedhin wrote an article on diversity in publishing. But instead of investigating the story, LitHub never covered it at all—even as, for the wider public, it was the most consequential publishing story of the day. It also never covered the controversy over publisher Paul Coates, father of famed writer Ta-Nehisi Coates; last year, the National Book Foundation conferred an award on Coates père, who runs Black Classic Press, a publishing company that, as Arc reported, publishes a range of authors with antisemitic, homophobic, and misogynist views.

Nor did LitHub ever mention perhaps the biggest antisemitic scandal in publishing in many years, the spreadsheet, titled “Is Your Fav Author a Zionist?,” which in 2024 tracked writers by their putative views on Israel.

Ron Charles, The Washington Post’s celebrated book critic, has made no secret of his own liberal leanings (which can be gleaned easily from his popular, chatty newsletter).“I’m not a frequent reader of LitHub, except for their handy book review samples service,” he said in an email. “That said, any efforts to try to stigmatize ‘Zionist’ authors or to sever ties with Israeli publishing houses as a way of expressing disapproval of the actions of the Israeli military would seem, to me, illiberal and contrary to the spirit of open literary exchange.”

Diamond and publisher Andy Hunter never replied to my queries about these omissions, though they were otherwise gracious with their time. In a separate exchange, Hunter wrote the following: “Personally, I am adamantly against any form of anti-semitism and I am also anti-violent and do not condone political violence. While the Lit Hub staff is filled with diverse viewpoints, I am certain all members of the Lit Hub staff find anti-semitism abhorrent. I think our readership is sophisticated enough to understand that critiquing state or institutional violence does not constitute a condemnation of a people, culture, or religion.”

LitHub was founded in 2015 by Morgan Entrekin, the publisher of Grove Atlantic and a staple of the Manhattan book party circuit, and Terry McDonell, like Entrekin a publishing Big Man on Campus, having edited Sports Illustrated and hung out with Hunter S. Thompson. The site was supposed to be “a new home for book lovers,” wrote The Wall Street Journal upon its launch. Today, “Literary Hub is supported by advertising and our membership program. It was initially funded by Grove/Atlantic with no outside investment, but is now self-supporting,” Hunder told me.

In many ways, LitHub remains what it was at the beginning, a clearinghouse for book excerpts and author interviews, as well as some reported features. A recent visit to the expertly-designed site finds an essay by novelist Michael Jerome Plunkett on the unexploded ordnance from the Battle of Verdun and a conversation about editing between Sasha Weiss of The New York Times Magazine and the critic Merve Emre. LitHub also owns Book Marks, a book review aggregator I have found highly useful over the years. (As I was recently interviewing the novelist Gary Shteyngart for an unrelated article, he brought up Book Marks unprompted, having apparently found it as useful a guide to new books as I have.)

Very shortly after LitHub was founded, the entire world changed—and culture has been grappling with that change ever since. That change came on the evening of November 8, 2016, around the time that the state of Wisconsin was called for that year’s Republican presidential nominee, one Donald Trump, whose favorite book is his own 1987 treatise The Art of the Deal. He likes the Bible, too.

Three days later, Diamond published a post on LitHub titled “The Literary is Political: On Poetry, Resistance, and the Shift from Sadness to Resolve.” Though he did not purport to speak for the literary world, he adroitly captured the mood in the publishing houses of Midtown Manhattan. LitHub would be “a space for bearing witness and calling to action, for testimony and prosecution, for lamentation and, when possible, celebration,” Diamond wrote.

For publishing, the political turned out to be profitable. Books like Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury, about the tumult in the early days of Trump’s first term, became genuine sensations, the first in a while that had nothing to do with dragons or boy wizards. “Sales have exploded,” New York magazine observed in December 2018, with 4.2 million political books sold that year and the holiday season still looming. The Washington Post saw subscriptions skyrocket, while viewers flocked to MSNBC’s primetime line-up. The world was on fire, and Americans were shelling out to witness the burning.

LitHub hewed closely to liberal cultural sensibilities. In the summer of 2020, the acclaimed writer Rebecca Solnit published “The Slow Road to Sudden Change,” an essay on the social justice protests roiling the nation, one of many LitHub articles about Black Lives Matter. In a 2022 excerpt from his soon-to-be published book, American Prospect editor Robert Kuttner urged then-president Biden to make “bold progressive choices.” On culture-war topics like masking, LitHub hewed left: in 2023, LitHub published an article by a writer petitioning a major literary conference to keep its pandemic-era mask mandate.

Later that year, on October 7, Hamas attacked Israel, killing 1,200 people, most of them civilians. LitHub stayed silent about the attack until October 16, when it published a post, “Here’s how you can help people in Gaza right now.” The post denounced “Israel’s brutal assault on Gaza,” making no mention of the events that led to Israel’s devastating military response, which has to date killed more than 60,000 Palestinians (the figure does not distinguish between militants and civilians). “Now in its eighth day, the devastating humanitarian crisis in Gaza is deepening, with Israel cutting off access to food, water, fuel and electricity for the besieged enclave’s 2.3 million residents,” Dan Sheehan wrote. He cited casualty figures from the Palestinian Health Ministry, without mentioning, as other publications do, that the ministry is run by Hamas, which makes its statistics controversial.

The political turned out to be profitable.

Sheehan is the Ireland-born, Wyoming-based founder of Book Marks, the aforementioned review site; he is also the author of Restless Souls, a novel about a PTSD clinic in California. Since the October 7 attacks, he has published dozens of pro-Palestinian articles on LitHub, charging Israel with trying to “erase all evidence of Palestinian life, Palestinian humanity, from Gaza,” as one of his posts put it. With Sheehan’s prolific pro-Palestinian output, LitHub has have taken a determined step into activism, even as many other outlets, stung by the anti-woke backlash, have rethought the commitments they had made in 2020. LitHub has touted those commitments with newfound enthusiasm.

When the poet Rupi Kaur decided not to attend a Diwali event at the White House, she issued a “blazing, courageous statement”; Sheehan chastised “American writers [who] continue to be silent on Gaza,” contrasting them with “Sally Rooney … one of the literary world’s most vocal and eloquent advocates for Palestinian rights.” Meanwhile, according to writer Omar El Akkad, in a LitHub interview, Joe Biden had nothing but “blood lust” for the Palestinian people.

“These are intensely political times, and a successful publication cannot possibly please 100 percent of the people 100 percent of the time,” Diamond told me in an email. He pointed out that “there are large, easily identifiable sections of LitHub devoted to less obviously political topics; not to mention that no one *has* to click on articles with more overtly political headlines. There’s plenty of stuff at LitHub for everyone.”

Sheehan is outspoken on social media. In one post, he compared The Free Press and Tablet—the former edited by the outspokenly Jewish journalist Bari Weiss, the latter an explicitly Jewish publication—to Der Stürmer, the Nazi-era propaganda rag. Part of the offense, apparently, was an article questioning the veracity of Palestinian fatality figures, which, as noted above, are released by a Hamas-run health ministry and difficult to independently verify.

Meanwhile, there have been very few LitHub posts on the atrocities taking place in Sudan since 2023. Nor, in the last two years, has there been especially aggressive coverage of the war Ukraine, where as many as 500,000 people have been killed overall (there were more such posts in 2022), including more than a dozen journalists. It’s true that Gaza is a deadly place for journalists, with most deaths coming at the hands of the Israeli military, but LitHub has evinced little interest in Hamas’s violent oppression of reporters, nor in the numerous countries around the world with deplorable records for political or artistic freedom.

The rise of antisemitism has received virtually no coverage at all. “There Are Bigger Problems in the World Than ‘Antisemitic Literary-Related Incidents,’” went a February 29, 2024, post by Maris Kreizman, after the Jewish Book Council started an initiative to chronicle antisemitic incidents in the publishing world, which by all accounts were becoming more common. LitHub seemed to only platform Jews who, like Kreizman, voiced anti-Zionist views. In a 2024 post, the writer Enzo Traverso lamented “a new, imaginary antisemitism aimed at criminalizing any criticism of Israel.”

In an article published on LitHub on February 27, 2024, Northwestern professor Steven W. Thrasher dismissed a New York Times investigation into the rape of Israeli women by Hamas. “I found little of news substance in the story,” he concluded, describing it as “attempt to use charges of racialized sexual violence to justify the genocide of tens of thousands of Palestinians.” He called the Times story discredited, even as the United Nations had found that “[t]he growing body of evidence about reported sexual violence is particularly harrowing.” (Thrasher did not respond to my request for comment.)

Liberal Israeli writers like Amir Tibon, a journalist who survived an attack on his kibbutz, Nahal Oz, and has written critically of the current Israeli government, get very little attention from LitHub, to say nothing of novelists like Amos Oz or Etgar Keret. “Lithub is part of a wider trend in the book world of boycotting and harassing those perceived to support Zionism,” Anti-Defamation League spokeswoman Jessica Cohen told me, pointing to the site’s publication of Mohammed El-Kurd, whom she called “someone who regularly employs violent antisemitic tropes and has wished that ‘every single Zionist perish.’”

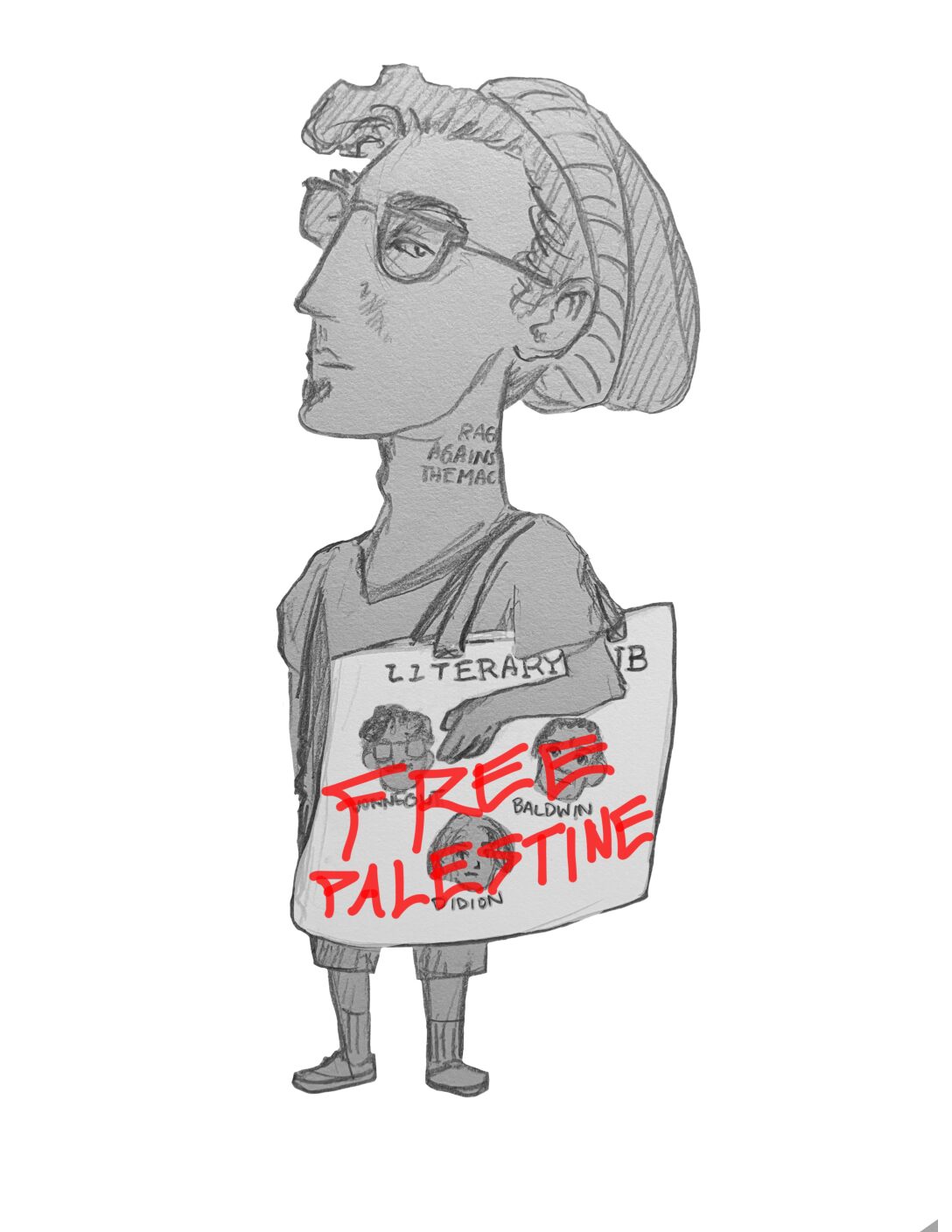

Sheehan has been more or less explicit about the goal of marginalizing pro-Israeli voices in literary culture. “It’s been like pulling teeth trying to get these institutions to divest from Israel, but it does seem to finally be happening,” he said in his interview with Akkad. After former New York Times columnist Pamela Paul called LitHub “the defacto clearinghouse for pro-Palestinian literary-world sentiment,” Sheehan joked on X that she had given him “a new tote bag idea.”

For some writers, including many Jewish writers, little of this is funny. Some of them seem to feel that the site is emboldened by the broader publishing industry. “Literary Hub is consistently committing acts of editorial and professional malpractice,” said the writer and editor Erika Dreifus, who authors the newsletter The Practicing Writer and posts frequently on social media about Jewish matters. “They are more propagandistic than journalistic.” Dreifus says that her view has become commonplace. “I know I’m not the only one, because I hear it from other Jewish writers,” she said.

Diamond largely dismissed these concerns. “Writers themselves (by and large) are deeply political people,” he said, “so it would be strange for a website devoted largely to books and literary culture to avoid politics.” He added that people who disagreed with LitHub’s views “have every right to respond through comments or letters (as many have done), and to write their own op-eds in response (as some have done), at outlets they feel align more fully with their opinions.”

Entrekin, the site’s co-founder, who has no role in its editorial policy today, struck much the same note. “We do not necessarily agree with every word they write or say, but we support their right of free expression,” he said in an email. “Likewise, we support your right to criticize or rebut anything that LH or any of its authors have written or said.”