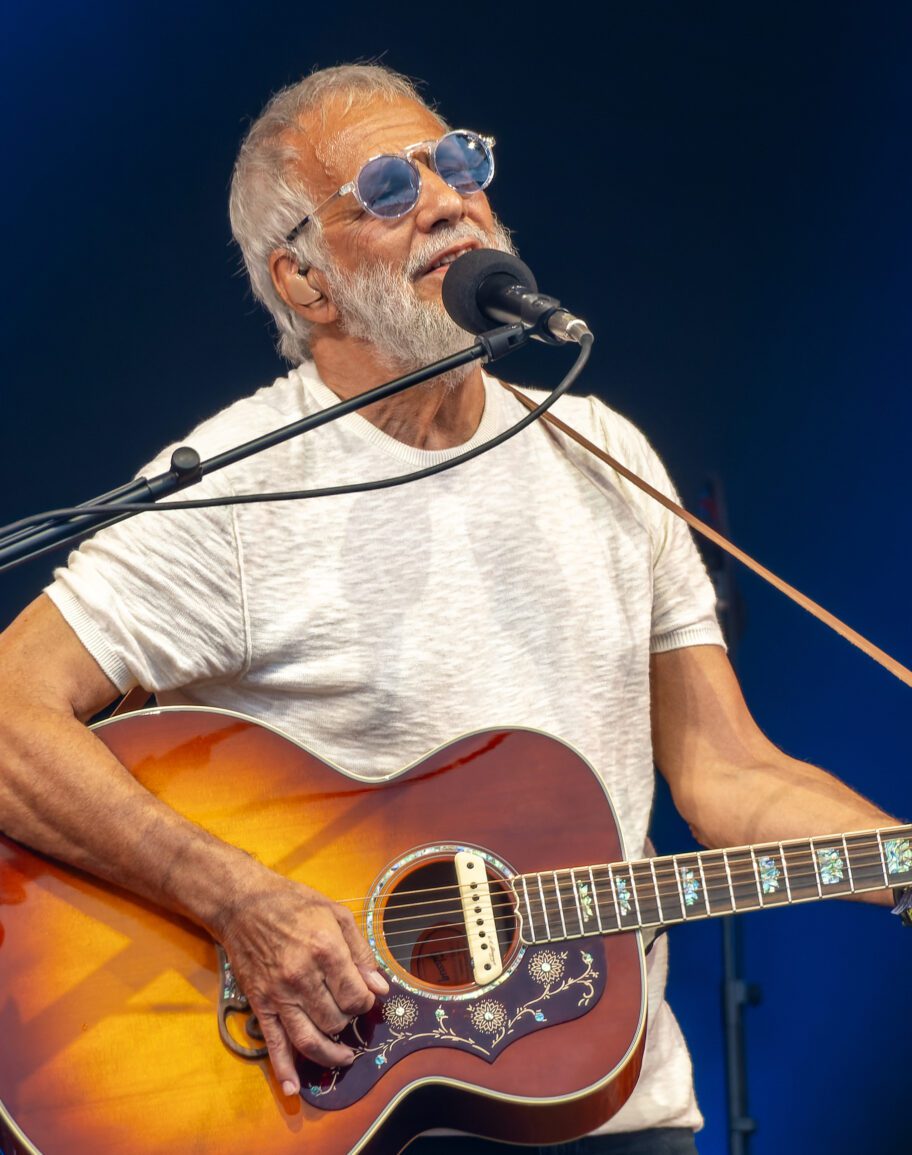

Long before the folk legend Cat Stevens became Yusuf Islam, he was Steven Georgiou, the London-born son of a Greek Cypriot father and a Swedish mother. He adopted the name Cat Stevens in 1966 as he rose to fame in the 1960s and ’70s folk-pop scene. Following his conversion to Islam in 1978, he took the name Yusuf Islam to reflect his new religious identity. Now 77, Stevens goes by both monikers, and his new memoir, Cat on the Road to Findout (Genesis Publications, 2025), helps make sense of why, offering an introspective look at a life more discussed—in the rock press and elsewhere—than understood.

The name changes throughout his life reflect not a series of radical breaks but an evolution, one rooted in reflection, growth, and a search for meaning. This more grounded story contrasts with the reductive, Islamophobic narrative of a pop star gone radical, the precocious musical darling who disavows his gift in favor of an extremist, anti-Western religion. The memoir pushes back against this view, offering a personal history of a life intermittently suffused with political engagement.

Stevens grew up in postwar London, above his family’s restaurant, with parents and siblings who nurtured his artistic and creative talents from a young age. He reflects on his rise in the folk scene, modestly recounting his composition of several enduring classics (even decades on, “Moonshadow” and “Father and Son” still hit); his near-fatal battle with tuberculosis; and his early ambivalence toward fame. His gradual conversion to Islam, precipitated in part by a near-death experience at sea and his growing disillusionment with the music industry, is framed not as a rupture, but as a natural extension of his lifelong search for meaning.

Moreover, Stevens’s turn toward Eastern spirituality was not an anomaly, but part of a broader pattern among many of his artistic heroes and contemporaries. Indeed, one of the memoir’s richest offerings is its account of Stevens’s artistic inspirations. His admiration for Bob Dylan, whose Jewish background and personal journey of spiritual exploration—he was, for a time, a born-again Christian—informed the political consciousness of his music, shaping Stevens’s own contributions to folk. Likewise, The Beatles loom large, not just as musical trailblazers but as spiritual seekers who were no strangers to controversy. Understood against the backdrop of George Harrison’s foray into Hinduism and the Hare Krishna tradition and John Lennon’s anti-establishment spirituality, Stevens’s journey into Islam was not an outlier, but one more case study of a cultural generation yearning for more than fame and material success.

However, Stevens’s embrace of Islam was riddled with challenges from the onset. The 1970s were a time when British understandings of Islam, and misunderstandings of why a Greek Cypriot would turn to Islam, were shaped by the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the 1979 Iranian Revolution. In that milieu, Islam was seen as the antithesis of Western civilization. Stevens, then Yusuf Islam, quickly became a target of the media, who narrated his conversion as evidence of mental instability. One inflammatory tabloid article from the mid-eighties, run under the headline “CAT STEVENS JOINS THE EVIL AYATOLLAH,” claimed Stevens was living in Iran as a beggar, which prompted him to pursue legal action.

Stevens’s turn toward Eastern spirituality was not an anomaly but part of a broader pattern among many of his artistic heroes and contemporaries.

This early media treatment was a precursor to the infamous controversy surrounding his comments on Salman Rushdie in 1989, and indeed no discussion of Stevens’s public life can avoid the media firestorm that has followed him since. The context: after Rushdie’s publication of The Satanic Verses, which offended many Muslim communities for its portrayal of the Prophet Muhammad, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie’s assassination. Around the same time, Stevens was invited to give a public talk at Kingston Polytechnic (now Kingston University), in London, about his journey to Islam. During the Q&A following his talk, a journalist asked him whether Rushdie should die for writing his book. Stevens, in a feeble, off-the-cuff attempt to explain the Islamic legal tradition’s position on blasphemy, gave a vague and ill-considered answer, admitting in the memoir that he “forgot to mention the questionability of the dreaded fatwah.”

This was a crucial omission, one that triggered immediate public outrage. He attempted to clarify his comments the next day and has since stated that he never supported the fatwa, condemning the call for vigilante violence and affirming the importance of adhering to peace and public order.

But the damage was done. Critics were right to interrogate his remarks, which lacked clarity; at worst, they seemed to be calling for violence, and at best they seemed naïve about the weight of the moment. Several journalists have since critiqued his statements in depth. Stevens failed to fully grasp the gravity of what he was stepping into: not just a theological debate, but a global geopolitical crisis involving freedom of speech and the fraught positioning of Muslims in the West. His casual tone, perhaps intended to showcase eccentricity or even dark humor in the world of celebrity, now seemed ominous.

Yet what’s often overlooked is how disproportionately this episode has been attached to Stevens’s legacy, particularly in comparison to other public figures who have made harmful comments without facing decades of reputational damage. For instance, fellow white British singer Eric Clapton infamously espoused white nationalist views in an on-stage rant in 1976, and while he faced some initial backlash, his legacy remains mostly untarnished. By contrast, Stevens’s ill-informed comments, rooted in a rudimentary understanding of the new theological tradition that he was, as a new Muslim, still learning about, continue to color public perceptions of him today. However poorly framed, Stevens’s comments have been wielded against him in ways that speak more to Western anxieties about Islam than to any serious engagement with what he actually said. In the memoir, he doesn’t issue a conventional apology, but neither does he disown responsibility. Instead, he draws attention to how little space exists for nuance when Muslims speak in public.

He also compares this incident to that of John Lennon’s infamous comment that The Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.” But whereas Lennon’s statement was treated as an individual provocation, Stevens’s words became, in a cultural climate already hostile to Muslims, representative of an entire religion. While Stevens’s comparing himself to Lennon might appear, to some readers, to downplay the political weight of his own comments, it offers us a poignant glimpse of his belief that, as a fellow famous white celebrity, he would be afforded an interpretive leniency afforded to celebrities of his stature.

But stepping into the public identity of a Muslim, particularly at a time of deep geopolitical tension, meant that this kind of casualness was no longer available to him. This episode therefore offers us a fascinating glimpse into the limits of celebrity immunity when it comes to religion, especially Islam. Stevens’s attempt to explain Islamic legal thinking around blasphemy wasn’t just clumsy; it revealed how ill-equipped he was for the gravity such statements would carry. Stevens approaches the moment through the logic of celebrity, according to which controversial statements may be seen as eccentric or merely symbolic. But as a Muslim, especially a public one, that kind of symbolic license disappears.

There’s a kind of innocence in Stevens’s misreading of the moment that makes his memoir feel especially human. His vulnerability doesn’t diminish the seriousness of the controversy, but it does invite a different kind of reflection on how uneven the terrain is for Muslims in public life, and how easily someone can stumble when they’re navigating that space for the first time. His story reminds us how race, fame, and faith intersect in unpredictable ways, and how they complicate the seemingly straightforward idea of “speaking one’s truth.”

The memoir also invites a broader contextual reading of the Rushdie controversy, one that’s often flattened in Western media retellings. Stevens’s reaction, fumbling though it was, reflected a sentiment shared by many Muslims in Britain at the time. The Satanic Verses caused genuine offense with its portrayal of the Prophet Muhammad, particularly among working-class South Asian Muslims already navigating life on the margins in Thatcher-era Britain. In cities like Bradford, with large Muslim populations, the book’s publication sparked protests that escalated into riots, culminating in an infamous book-burning event in 1989. While it’s crucial to distinguish between legitimate offense and the endorsement of censorship or violence, it’s equally important to acknowledge that Muslims, like any community, have a right to be offended. Stevens’s remarks, however ill-considered, were not made in a vacuum; they emerged from a moment of communal pain, political tension, and a desire among many Muslims in Britain to defend what they saw as the sanctity of their beliefs. (As it happens, English blasphemy law, which protected the Anglican Church from mockery, was not formally abolished until 2008.)

There’s a kind of innocence in Stevens’s misreading of the moment that makes his memoir feel especially human.

Another question arising from this media backlash is the relevance of the Rushdie fatwa to Cat Stevens in the first place. Why was a folk singer and philanthropist scrutinized through the lens of geopolitics and accusations of blasphemy? This episode highlights how media narratives are constructed to prioritize sensationalism, revealing the frequent mischaracterization of public Muslims. The media, as Stevens notes, was not interested in the complexities of his personal faith or his opposition to violence. Rather, it was interested in making him a symbol of Islamic radicalism—a goal with which he, against what might have been his better judgment, collaborated.

This media narrative persisted into the early 2000s. In 2004, Stevens found himself detained by immigration authorities in Maine, en route to Nashville, to record a new album with collaborators like Dolly Parton. He was detained on suspicion of terrorism, an episode whose absurdity he recounts well: while he was signing autographs for immigration officials, he was being treated as a potential threat (and he was eventually deported back to Great Britain). This incident became headline news that yet again cast suspicion on him for his Muslim identity.

Reflecting on his treatment, Stevens ties this experience to his refusal to meet with President George W. Bush while visiting the White House earlier that year, based on his moral opposition to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Stevens was there to meet with the director of the Faith-Based and Community Initiatives Project. Again, there’s a kind of earnest miscalculation in that decision—an assumption that one could both be invited into the highest halls of American power, then publicly snub the president, without consequence—that seems rooted in the kind of innocence that often accompanies whiteness and celebrity. This public stance, coupled with his detention, further marked him as a political figure in the eyes of the media.

Despite its political undercurrents, Cat on the Road to Findout is at its heart a deeply personal book. Stevens shares intimate memories of family life, fatherhood, and his evolving relationship to music. He talks about his return to recording, first through a cappella Islamic music for children and, later, through the rekindling of his relationship with musical instruments and his earlier catalog. Stevens also chronicles his founding of several Muslim schools in the U.K., including the first Muslim primary school to receive public funding. He presents these efforts not as a retreat from art, but as an extension of it, another form of spiritual expression.

Ultimately, Cat on the Road to Findout contests the narrative that Cat Stevens “disappeared” into the identity of Yusuf Islam, to become a figure of controversy and suspicion. This reductive narrative says more about how we as a public digest celebrity and difference than it does about him. His memoir offers us a rare glimpse into the spiritual and psychological terrain of an artist who turned away from fame to embark on a spiritually fulfilling journey. It also helps us reframe how we think about faith, especially Islamic faith, in the lives of public figures. What does it mean to convert to a religion that the West sees as suspect? How do we make sense of that choice without exoticizing or politicizing it?

“As Cat Stevens, more so as Yusuf Islam, I had a significant role to fulfill,” he writes. “I was uniquely positioned to become a glass portal through which the West could see Islam and Muslims could see the West. Having passed through the exhaustingly complex maze of everyday Western life and culture, and then been granted invaluable insight into the often-veiled ‘otherness’ of the Qur’anic view of the universe, I naturally wanted to share it. That didn’t make me a teacher, but more of a potential specimen for those who are searching for and pursuing happiness on all sides of the divide. Believe me folks, it’s out there.”