In 2006, Samuel Menashe became the first recipient of the Poetry Foundation of Chicago’s short-lived and oddly conceived Neglected Masters’ Award. Even on its face, the Neglected Masters prize was a bizarre award—as David Orr at The New York Times noted, “[t]his is what you might call the Prize for Not Getting Enough Prizes.” As well as a cash award, the prize included the publication by the Library of America of the handsome New and Selected Poems, edited by Christopher Ricks. On the attendant tour, Menashe came and read at my local bookstore, and I went along to see what a “Neglected Master” might look like.

In a more substantial sense, I was encouraged to attend the reading by both the recommendation of Ricks, whose lectures I’d attended at Cambridge University, and of Donald Davie, the poet who had written the introduction to Menashe’s 1986 Collected Poems. I knew of Davie because I’d studied with J.H. Prynne, one of Davie’s protégés, as an undergraduate, and so his opinion was particularly meaningful. But that same Orr piece that lays out the “left-handed compliment” regarding the award’s peculiarity goes on to ask the crucial question, “Does this collection help justify the muddled honorific that gave it life?” Of course, for every Emily Dickinson unfairly neglected in her lifetime, there are hundreds, nay thousands, of poets rightfully neglected. Fortunately, Orr answers with the emphatic conclusion about Menashe’s work: “It does.”

I was a little worried. Poets can be pretentious; the evening could be a dud. And, as someone just beginning to make my way in the world of letters, I had conflicted feelings about a “Neglected Master.” It was all-too-easy to think that if I tried to make a living doing the type of experimental writing that had felt meaningful to me over the previous decade, I could be “neglected” myself. If someone who wrote accessible poetry and, moreover, was championed by some major names could live in forsaken poverty for half a century, what chance did I have? And for every abandoned poet who won a belated award, how many just remained neglected? Who would feed and clothe my baby daughter?

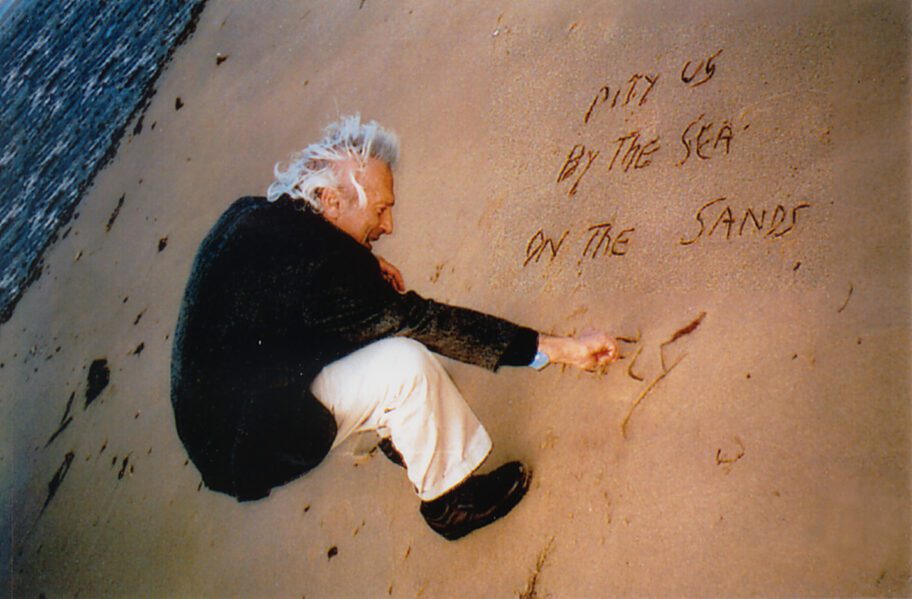

I didn’t overthink it though, and it was a fun evening. I know it was Sep. 13, 2006, three days before Menashe’s eighty-first birthday, because he inscribed the date on the title page of the book I bought that evening. Menashe talked and read from his book in a way that was to become familiar to me. It was his gift and his shtick to have memorized all of his own poems as well as the poetry of others. So, though the distinctive LoA book was in front of him, he would recite by heart in a slightly reverential singsong that highlighted each poem’s succinct prosody before lapsing into his more normal gentle brogue to explain what he was trying to do in the poem—or to recall the memory that gave it rise.

As is common for poetry readings, the event was sparsely attended, which gave me the chance to talk to Menashe and explain that I was an editor at a small but growing journal of Jewish thought and culture and I’d love to talk to him more at some point. He was open to it, and, before we parted, he wrote down a few poems on the blank pages at the end of the book. As I soon realized, just like wearing his trademark suspenders, this was a customary act of his, always reciting or writing his poems in conversations.

Menashe, who died in 2011, was utterly charming. Though devoid of confession, politics, plot, or modern influence—and therefore largely unsuited to the world of professional American poetry—his oeuvre is accessible and inviting to readers and listeners alike. His habit of reciting poetry without breaking conversational rhythm, but elevating it, was a treat, and his warmth was infectious. In her reflection on The Shrine Whose Shape I Am: The Collected Poetry of Samuel Menashe (for which she wrote a foreword), Harvard professor Stephanie Burt referred to this tendency to imbue language with intensity as a type of “holiness.”

Though talking about his poetry rather than his conversation, Burt likens Menashe’s use of language as “being set off”—like the Sabbath is separated from the mundane world. There is indeed a way in which he turns workaday phrases around and gives them a special aura. Burt discusses how “regular language and regular work, becomes, in the poems, a matter of sound.” She quotes an early poem, “Cargo”:

I am made whole by my scars

For whatever now displaces

Follows all that once was

And without loss stows

Me into my own spaces

For Burt, this is evidence of Menashe’s craft; it is “a graceful chiasmus, a gathering of phonemes around one metaphor, rarely equaled in English … ” But Menashe equals it many times, as in: in “To Open,” whose almost punningly Objectivist title belies its spirit of delight: “Spokes slide / Upon a pole / Inside / The parasol.”

His poems are, as Burt points out, “startlingly short,” and the Irish poet Derek Mahon called Menashe’s process one of “compression and crystallization.” They contain no complex vocabulary, nor do they require particular decoding because of their brevity. They sit there simply on the page, available at a glance, but they also reward those who want to spend more time reading them out loud or sitting quietly with them.

Menashe would recite in a slightly reverential singsong that highlighted each poem’s succinct prosody before lapsing into his more normal gentle brogue to explain what he was trying to do in the poem—or to recall the memory that gave it rise.

In 2000, when I finished my graduate courses in literature at Yale and moved to New York, it felt like the new, growing internet would be where thoughtful people talked to one another and wrote about the world. For me, this would be conversations about Judaism and texts from a broad Jewish perspective. My friend Jay Michaelson and I set up Zeek, a Jewish journal of thought and culture, and were ready to go live in September 2001 only to have to delay until January 2002 because of 9/11. With the benefit of hindsight, the racist, inward-turning response to that attack shaped many current trends in U.S. society. At that pre–social media moment, though, it felt like the people could travel together on this new information super-highway and conquer the old bigotries.

We published Zeek online exclusively for a couple of years, drawing each month from a wide variety of people who, like us, would write for free about contemporary culture for the honor of being edited and the hope of bringing some enlightenment to the world. We found that funders didn’t trust “online” publications, so in 2004 we started to make a beautiful, sixty-four-page print journal to bring in funding, to grow a little, and to pay for costs, events, and publishing.

I have no recollection of why I chose this particular poem, but I asked and received Menashe’s permission to reprint “Salt and Pepper” in the Fall 2006 edition of Zeek. Again, in that poem, there’s a delightful rethinking of a cliché, foregrounding what it means to develop “salt and pepper” coloration as one ages. Sprinkled with double meaning, the poem notes how, with the “zest” for life developed over many “seasons,” comes a fear that, of course, with the condiment metaphor, manifests as “shaking.”

Here and there

White hairs appear

On my chest—

Ages seasons me

Gives me zest—

I am a sage

In the making

Sprinkled, shaking

At the time—and related to those early possibilities of the internet that had attracted us—there was a Jewish cultural resurgence in New York. Following the launch of the social justice organization Avodah in 1998 and with musician John Zorn’s Tzadik record label as a surprising model, many of us were inspired to influence the world with excellence, entrepreneurial spirit, and a high level of Jewish engagement. As well as Zeek, Heeb, Jewschool, Mima’amakim, and Nextbook (the precursor to Tablet) in the writing space, the music label JDub Records, environmental organization Hazon, human rights organization Rabbis for Human Rights–North America (now T’ruah), and the egalitarian Torah communities around Hadar—among others—were founded in the first few years of the millennium.

With New York as our playground, we turned to overlooked artists and traditions for new, creative models for a vibrant Jewishness. Religion was a part of it, but not necessarily an important part. At eighty, Menashe was older than anyone else involved, but he was spry and happy to be part of this New Jew scene. I hung out with him a few times in 2006 and 2007, but I already had a full-time job, a part-time job, and a new baby, so my time was limited. My friend Jake Marmer, then the editor of Mima’amakim, was a grad student and not yet a father. He had more time for the friendship.

Marmer told me how one time he took a date to a Menashe reading.

As we were walking in, he said, “Jacob [it was always “Jacob,” never “Jake,” just as he himself was always “Samuel” and not “Sam”] … I need to speak about something important after the reading.” When we approached him afterwards, having waited for all of the others to leave, he said, “I had a great idea for your doctorate. Why don’t you write it … about ME?”

Marmer had heard of Menashe through a friend at Mima’amakim who had read Menashe’s work and passed it along to him. “I found his number in the phone book and left a message inviting him to the Mima’amakim gig,” Jake told me. “He called back the day of and said he’s coming. That’s how we met!”

I had heard about that same gig through more conventional channels, and was delighted to see that Menashe happened to be there. That evening we heard a variety of different poets perform, including Menashe and also including Marmer’s punk-poetry band Frantic Turtle. Mostly the poems were recited by their authors alone at a microphone, but not Frantic Turtle. Marmer recalls Menashe saying to him after the same gig, “I’m just an old fuddy-duddy … but why does it have to be so loud?”

Halfway through the punk-poetry set, I ended up outside on the quieter street talking to Menashe (“call me Samuel”) about the evening’s poetry. Though I had a poem or two published in Mima’amakim, I was not reading that night, so there was no awkwardness of comparison. Our conversation started with gentle thoughts about the poets we had heard and meandered through his new poems, the state of his book tour, my new, my baby. He was not a dazzling, charismatic conversationalist, but he was a thoughtful, pleasant companion who was always listening for an interesting turn of phrase.

I had come from Leeds, England, Jake from Odessa, Ukraine, and others in the scene from Florida, California, the Midwest, and other parts of North America. New York’s magnet had drawn us. Despite, or perhaps because, he was older and came from yet another different background, Menashe fit right in.

Sometime in the fall of 2006 I went downtown to meet Samuel at his apartment on Thompson Street. He had lived in the same apartment in Greenwich Village for fifty years, and it was both surprisingly empty and surprisingly squalid. As he points out in “At a Standstill,” his stagnating living space was both material and symbolic:

In this kitchen

Where I do not eat

Where the bathtub stands

Upon cat feet—

I did not advance

I cannot retreat.

We went to a diner around the corner and had a late lunch.

WNYC, the local public radio station, made a video of him reading that poem in his apartment at about the time I was there. They do a beautiful job of capturing Samuel’s feline grace even when ruffled by old age. But the portrayal of his apartment is kind. In the video, you can see the peeling paint and detritus, but you can’t see how pervasive it is. You see the mess but not the squalor.

When Jake and I heard that Samuel was sick, in the winter of 2006, we were upset but hopeful that he would recover and relocate. The apartment was clearly unhealthy for him. As a young man, he had come back from his time writing and studying in London and Paris and moved into a building whose poor condition his father disapproved of, even in 1956.

He and a sprawling sickly-looking plant cohabited, just the two of them, in an apartment that, not to mince words, smelled of piss. Part of his situation had come about because he was a confirmed bachelor who didn’t particularly care to take care of himself, but partly because it was an extremely cheap option for a man of few financial means. The Neglected Masters award came with a prize of $50,000, and it was easy to see how that might be all that stood between Menashe and penury. His cost of living verged on zero, but by the time Jake and I got to know him, Menashe could no longer easily withstand the rigors of that tenement lifestyle.

His landlord saw the boutique Sixty SoHo hotel go up next door at 60 Thompson Street and, by Samuel’s account, didn’t really care about the current residents of 75 Thompson Street, only about the earnings he might enjoy from selling the increasingly gentrified location. He may have won some belated recognition, but at the time Samuel’s future was quite uncertain.

Samuel had gone from receiving almost no visitors before his award to receiving rare visitors afterward. One of those visitors was the British-based artist Pamela Robertson-Pearse. While there on assignment from the British publisher Bloodaxe Books, she captured his apartment in this period in her deeply sympathetic film Life is Immense: Visiting Samuel Menashe.

It was no accident that Robertson-Pearse and Bloodaxe had shown as much interest as any artists or publishers from west of New York. From the time of his wartime journey over the Atlantic as the nineteen-year-old Samuel Weisberg—along with twenty thousand other G.I.s on the requisitioned Queen Elizabeth—Menashe enjoyed a mutual affection with Britain and Ireland.

Orr had pointed out that “as an American poet, he appears to have done almost everything wrong. He didn’t teach creative writing, didn’t ally himself with his more sociable peers, didn’t serve on many committees, and didn’t finagle his way into many anthologies. He appears mostly to have just … written poetry.” Orr was not exactly right—Menashe had indeed taught at a couple of American colleges—but the life of a writer seemed more natural to the English, for whom Menashe’s exoticism as an American and as a generally non-religious Jew provided quite enough fascination without the need for any more outsider status.

Whether Davie or Ricks or Neil Astley, who interviewed Menashe for the Robertson-Pearse video, many of Samuel’s champions tended to be English. He even remarked on that to me early on, in his gentle, forthright way, when I mentioned my connection to Ricks. Perhaps because, with my Ph.D. recently wrapped up, I didn’t know what I was going to write next, Samuel never proposed that I write about him—after all, I’d just met him and already published one of his poems. But, with Jake’s words in my ear, I always half expected him to make some sort of suggestion.

“As an American poet, he appears to have done almost everything wrong.”

While eating at the diner, Samuel told me his story, including an early tale of his very first poetic champion, Kathleen Raine. One of the foremost scholars of William Blake, Raine was excited by some of the poems that he sent her just as his three-month visa to the U.K. was expiring in 1960. Feeling a sense of urgency, Samuel missed his train and only arrived at Raine’s house in Cambridge after she’d finished her family dinner. It was perfect timing, and would have been premature if he’d caught the earlier train—or at least that’s how he told the well-rehearsed story.

Despite demurring about her lack of contacts in London, Raine had clout, as a professor of poetry at Cambridge, and a sense of which of Menashe’s poems might interest Victor Gollancz, who ran a well-respected poetry imprint. Apparently, she had enough influence and sense that her letter of recommendation, by Samuel’s telling, was enough to get him his first book, The Many Named Beloved, in 1961.

For the next fifty years he would be regularly, if infrequently, published by significant poetry journals, with even more occasional elegant, slim monographic volumes containing his tiny, surprisingly robust poems. In To Open, published by Viking in 1974, Samuel was already listed as having published in The New Yorker, Harper’s, Commonweal, Encounter, The Times Literary Supplement, The Yale Review, The New York Review of Books, and The Iowa Review. However, it took ten years after his first book came out in London for him to publish his first volume in America.

Menashe was almost adoptively British. The relatively popular—for poetry, at least—Penguin Modern Poets series that came out in London in the mid-1990s curated thirty-nine contemporary poets. Of those highlighted, only Menashe, in volume seven, was an American still living in America. As Burt points out, this sporadic recognition meant that Samuel needed to be “reintroduced over and over, in volumes whose contents overlapped, across decades, to audiences on both sides of the Atlantic.”

Right at the end of 2019, eight years after Samuel’s death, Bhisham Bherwani and Nicholas Birns published a new volume of Menashe’s collected poetry.

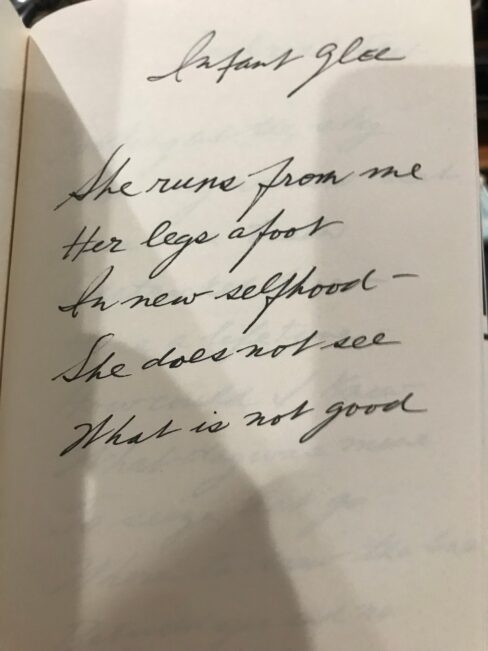

With delight, I noted that Bherwani and Birns had collected many of the poems that Samuel had inscribed in my books: “Leavetaking,” “More to Come,” “Railroad Flat,” “Die-hards,” and “Birds.” I knew that in his eighties, Samuel had been free with his words and working on new projects, so I wasn’t surprised to see that the editors had found other new poems that they considered finished. But what I didn’t find was “Infant Glee,” the poem that Samuel had inscribed to me, my wife, and daughter on Sept. 25, 2006, along with wishes for “Long life, joy!”

It seems to be Samuel’s revisioning of Blake’s “Infant Joy” and, as Birns told me in December 2021, was probably part of the “Triptych” poem series that he was writing about his mother.

She runs from me

Her legs afoot

In new selfhood—

She does not see

What is not good.

It’s still rough, the notches are not fully polished, but it has Samuel’s trademark rhymes (“me,” “see”; “hood,” “good”) as well as the slight twist of expectations around “afoot.” We find, as the line turns, that “legs” are “afoot” because of both the commonplace—physical location of feet at the end of legs—and the observed: her legs are “afoot” because they are how she “runs” to give her agency and “new selfhood.”

That word “selfhood,” when pushed ever so slightly by being the pivot of the poem, also offers a double meaning. With just a dash of stress it becomes not just an abstract noun referring to the quality of individuality, of agency, but also a “hood” of the “self.” This hood means that she “does not see / What is not good.” Unlike the pure, innocent joy of Blake’s two-day-old child—“I happy am, / Joy is my name”—Samuel’s infant’s glee is not just the speechless delight of a child, it is willful blindness by dint of a developing ego.

The last time I saw Samuel was in a Veterans Administration hospital in midtown Manhattan. Jake had reached out in the fall of 2007 to tell me that Samuel had been ill. When we got there, gained entry, and eventually found him, he looked unwell. His warmth and tendency to linger on words was now tinged with anxiety. His small but robust frame was now gaunt. He had shed his suspenders and pounds of weight he could ill afford. He had told us the previous winter that he thought his Dec. 17 show at the Bowery Poetry Club would be his last, but at the time I thought he was exaggerating. This time, not.

In my memory, the VA hospital was unlike any other hospital I have ever visited. There were steel hallways and beds but almost no people: neither patients nor staff. It felt like Samuel could expire at any moment and no one would notice: no friends, no family, no ward-mates, no medical staff, no poets. He was pleased to see us—he still had his joie de vivre—but he declined to talk about any specifics of his illness. He asked after our young families and our careers: my daughter, Jake’s band!

It was hard to see how he would escape this institution. Or if he did, where to? Even if his Thompson Street apartment hadn’t already been snaffled up by New York’s developers, how could he live on his own? We kept up our spirits for him, but it was a hard visit. Like one of Samuel’s own poems, it was a mundane event—a hospital visit—that had odd rhymes and echoes. As a fellow writer at New Jew events, he was a peer of ours and somewhat a friend. As young colleagues of a celebrated, neglected master, we were paying homage and hoping these were not last respects. As a wise old figure, Samuel gave me leave to once again say goodbye to my grandfather. As an inheritance, a thread ran from Blake, to Raine, to Menashe, to maybe us, maybe my daughter.

The lack of people in the hospital must have dented his quality of life, but I think what most worried him was being forgotten as a poet. This vocation that he never knew was possible—he had thought that “poets were dead immortals”—had maintained him for half a century. Over that time, as first Ricks and then Bherwani and Birns had shown, Samuel had turned and turned everyday English and found that, under our noses, in our very mouths, were profound insights into how we could understand the world.

When he finally died in 2011, I had lost track of him in the labyrinthine VA system. He had stopped calling Jake and there seemed to be no trace of him in his old flat on Thompson Street—I received no response to the Hail Mary letter I wrote there in 2008. By 2011, anyway, any whiff of poetry on Thompson Street had been wiped away by hip, capital construction. But Ricks’s Neglected Master title seemed to have done the trick. Remembrances sprang up all over the lettered world, from The Guardian to The New York Times to the Forward to Bloodaxe Books and Poetry America.

By then, too, the New Jewish Culture had mostly died out or become the newer face of the old Jewish culture. Zeek was bought by Jewcy, where it was neglected, mislabeled, and mistreated, then by the Forward, where it limped on for another year. Time had moved on; my infant daughter was talking and precociously reading. Professionally, I followed some writers and brought some others to the Forward. Some took their niche successes in Jewish culture and moved to be editors, CEOs, writers, artists in the larger, secular world. The cultural moment was gone, along with most memories of Samuel’s intersection with it.

Like the biblical forebears he sometimes echoed, or Emily Dickinson, or Gerard Manley Hopkins, or William Blake, Menashe exists in the context of millennia, not decades. His language is contemporary but somehow eternal in the way that meditation can exclude contemporary society. At one meeting, shortly after suggesting that Jake write his doctorate on him, Samuel gave me annotated copies of theses written by Irish poet Joseph Woods and Hebrew translator Jessica Sacks about his Jerusalem collection. He wanted his work to be absorbed by conversation, he wanted it to ascend into academia. On the Woods thesis he notes, with annoyance, “I’ve just telephoned Poetry Ireland of which Woods is the Director, but he is away on holiday.”

Samuel was both modest and deeply ambitious. He knew that everything had already been seen and done millennia ago but thought that his work of bearing witness was still of great value. He wrote a poem called “Nothing New” in one of my copies of Neglected Masters that is as apt an epitaph as any for a man who bequeathed us small, but beautifully formed, gems of perception.

Prophets foretell

And priests atone

And where men dwell

Their works are known —

How good it is to know

That nothing new is told

That all was done before

I was born to behold

The sky at dawn once more

Not knowing how or when

Now becomes then.