Late in Saul Bellow’s novel The Adventures of Augie March, the title character looks to an older mentor for guidance. “You will understand, Mr. Mintouchian, if I tell you that I have always tried to become what I am,” Augie says. “But it’s a frightening thing. Because what if what I am by nature isn’t good enough?” His mentor replies, “You must take your chance on what you are…. It is better to die what you are than live a stranger forever.” Teachers steeped in the ideals of progressive education give students advice like this all the time: live what you are, express what you feel, blaze your own trail. Some version of this imperative is the default message of commencement speeches all around the country. It is the theme of college application essays. It is the template for so many of our movies and novels. It is the closing resolve of Huck Finn to light out for the territory ahead of the rest. It is Thoreau’s attentive saunterer marching to the beat of a different drummer. It is the famous opening battle cry of Augie March: “I … go at things as I have taught myself, free-style.”

This heroic individualism in our common life begets, in school, what progressive educators call student-centered learning. Or maybe it’s the other way around. Maybe student-centered education fuels our ongoing expectation that we should get the life we want because we want it, and that the purpose of life is self-fulfillment and self-expression. With the understandable surge of attention to wellbeing in the midst of and then in the wake of the pandemic, our students can be forgiven for inferring that the purpose of life is to be well, and well on your own terms.

I’ve been inside the world of progressive education for thirty years now. This student-centered ideal is axiomatic and problematic. It is sometimes pushed to its limit and called student-driven learning. To nudge against this ideal can seem mischievous and even heretical. The growth of classical academies (a small but energized movement) challenges the whole edifice of progressive learning, including the individualism, the focus on what progressive educators call “voice and choice,” and the idea that the student’s peculiar interests and needs are the key to all real learning and the only road to engagement. I’m not writing here to assess the classical academies project, which is not offering a new methodology so much as it is describing a drastically different orientation and purpose for school. Even staying inside the boundaries of the progressive tradition, though—even holding to its orientation—we can draw on the tradition’s own resources to nudge and reshape and even recast entirely the ideal of student-centered education. And we need to do that because we don’t want our student-centered intentions to cultivate self-centered students.

To recast but not discard the ideal of student-centeredness outright, we might try to picture a curriculum that I’ll call You and Not You. Students should know that in some ways their education is all about their specific, peculiar life, but that more often education is about being introduced to the larger context of the world and to the needs and interests of the other people in it. The healthy approach would be both dialogical and dialectical. It would rock back and forth between student interest and immersion in the yet unknown. It would extend, and it would defamiliarize. It would balance Whitman’s very student-centered celebration of what is already part of your self with concentrated attention to what Matthew B. Crawford has called the world beyond your head. It would develop self-confident but not self-absorbed students.

Our approach in school is lopsided, and so we need to be more intentional about developing a Not You curriculum. Still, we should give the first half of the program its due. It is worthy too. Student-centered ideals humanize the experience of school and prepare students for a democratic life where everyone, at least ideally, is to be valued, treated equally, and viewed as an end in themselves. No one is a generic citizen. None of us is an interchangeable part in some civic design. In school, students are not versions of each other, crowding around an instructional mean. We want self-discovery. We value self-expression. Student-centered pedagogy responds to the personalities and biographies of actual kids. It favors exploration and idiosyncrasy. Though the technocratic language that dominates most discussions of school makes it sound otherwise, the goal of a student-centered school is not only preparation for adult things but actually finding yourself in the present. Prior to progressive student-centeredness, education involved memorization, recitation, and corporal punishment to keep students in line. The goal was receiving and mastering bodies of knowledge, not the transformation of yourself through an encounter with new knowledge. Thoreau, who experienced this kind of rote education, described in his twenties being astonished to learn he supposedly studied navigation in college. He did so, he noted, without setting foot in a boat.

Students should know that in some ways their education is all about their specific, peculiar life, but that more often education is about being introduced to the larger context of the world and to the needs and interests of the other people in it.

Making school about the student and their actual life and their emergence as individuals into larger communities has been a liberating trend. The You unit in my ideal curriculum would celebrate this without apology. I would want students to take lots of turns down lots of harbors in their version of navigation. I would hope their trajectories when they leave would not look the same. I would teach this unit on You with joy and conviction. We might even end with each student writing their own “Song of Myself.” If we’re lucky, every single student would leave having earned the description Emerson used of young Thoreau: “he does not postpone his life, but lives already.” That line could go on the report card, where letter grades like to squat. We would focus on the You so that a student becomes an authentic I, fully awake, fully alive. We would do all that—for half the year.

But then, as we transition to our new unit, buoyed by our shared understanding that a life is a singular thing, an instance of something only to the remote scholar, not to the present teacher, we would begin by saying, without apology, nonetheless, that, in the larger scheme of things, and this is a hard thing, but students, we would say: almost everything, in fact, is not you.

The risk of our student-centeredness, of all our understandable attention to the You, is that, unless we take tremendous care, we will mislead students about the nature of their own existence and leave out too much about the conditions in which all of us establish some relationship to the world. Generous, progressive educators need the pressure of these conditions to shape their optimism. This pressure, this interplay of the student and the world, should be the heart of how we describe what we’re doing. Instead, it is dissolved in our language of being student-centered.

We do a disservice to our students to suggest that school is only or even mainly about acquiring the tools with which to craft whatever life story they can imagine. Part of what you are doing in your life, we should suggest to them, is not figuring out what is inside you already but listening for possibilities and adapting yourself to what is outside you—picking up the various frequencies of the world, and tuning yourself to them, not mechanically, not by rote, but still tuning yourself to things outside yourself. It’s in the process of tuning to what is not you that you make your life unique. The way you adapt and move can be a life on Emersonian terms, for sure, a life of felt inspiration. It’s just that it doesn’t simply come from inside you. It’s You and also Not You.

No American not named Walt Whitman is a more famous champion of the individual, of the You, than Henry David Thoreau, but even Thoreau’s solitary thinker who doesn’t keep pace with his companions is out on his own path because he hears a different drummer. Something outside his own self is calling to him. He is summoned. He responds. In their book All Things Shining, Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly describe the task of the craftsman in similar terms: “not to generate the meaning, but rather to cultivate in himself the skill for discerning the meanings that are already there.” Emerson’s language was that the great thinker “yields to a current so feeble as can be felt only by a needle delicately poised.” Student-centered classrooms need more insistence on hearing, on discerning, and on yielding.

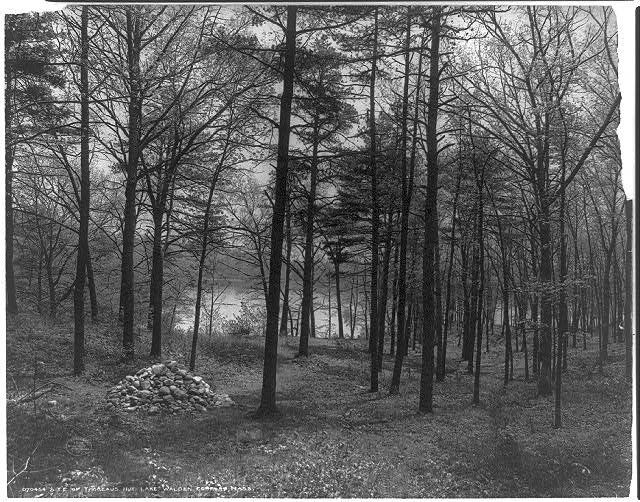

We might begin our Not You unit by exploring this large, existential frame, then: the You has limits and conditions that we don’t get to ignore. Again, Thoreau is a more subtle teacher. We may think of him organizing his Walden world so that he and his lone concerns live at the undisturbed center, but self-indulgence was not what he went to the woods for. Alone by the pond, he didn’t impose his vision on the world around him. In fact, he submitted himself with great discipline to the world he inhabited. Stanley Cavell commented that, at Walden, rather than putting the world under a microscope (though he did that with some ants), Thoreau is “letting himself be read” by Nature, letting himself be “confessed in it, listening to it, not talking about it.” Robert Richardson made the helpful distinction that Thoreau’s individualist credo, the lines printed for inspiration on note cards and dorm posters, is aimed at the social order, not the conditions of his physical life: “Extreme individualism in social matters is tempered by a sense of the limits of the individual in nature.” Reading Walden, we encounter someone bearing witness to the beauty and strangeness of the natural world, and in doing so developing an attitude about himself, as well as the world that is not himself.

Thoreau, in fact, forms his own You and Not You curriculum. The penultimate chapter of Walden is full of this larger apprehension: “We can never have enough of Nature. We must be refreshed by the sight of inexhaustible vigor, vast and Titanic features—the sea-coast with its wrecks, the wilderness with its living and its decaying trees, the thunder-cloud, and the rain which lasts three weeks and produces freshets. We need to witness our own limits transgressed, and some life pasturing freely where we never wander.” Note that our own limits are transgressed by nature. InThoreau’s celebration, we are part of something vast, but we are limited inside it. We don’t encompass it. This doesn’t diminish us; it plots the coordinates of our dignity. Thoreau’s summary in the conclusion of Walden, that “[T]he universe is wider than our views of it,” would make a good epigraph for the entire You and Not You course I go on imagining. Part of what we owe our students is an apprehension of our limitations and a commitment to adjusting ourselves to a world that is wider than our widest views of it. I read Thoreau as modeling humility before the conditions inside which we have our larger apprehensions, and a recognition that what we come to love and value and embrace comes to us from outside of us—what Thoreau in his journal describes as “the theme that seeks me, not I it.”

In his own great journal, The Inward Morning, American philosopher Henry Bugbee quietly picked up Thoreau’s mantle in this regard. Bugbee also wants to understand what being part of nature means for our assessment of our freedom and our purpose and sense of ourselves. “It is all very well to image our proper independence as responsible beings by talking of standing on our own feet,” Bugbee writes. “But this image, by itself, leaves us hanging in air. Let us not neglect to think of the ground being under our own feet; and let us not talk as if we placed the ground under our own feet.” Elsewhere, Bugbee plays with the paradox of freedom and constraint, of You and Not You, writing, “if we swim with necessity we discover power.” The pressure of necessity limits our freedom but enables and mobilizes other things we may in the end care about just as much. In life as Thoreau and Bugbee present it, we are navigating paradoxes, not connecting neat dots, and we are adjusting ourselves to a world that exceeds our understanding rather than simply asserting our chosen place in it.

Part of what we owe our students is an apprehension of our limitations and a commitment to adjusting ourselves to a world that is wider than our widest views of it.

I linger over this awareness of contingency and paradox, of our dependence on things that are not of our making and not in our control, because a humility about ourselves, as people first and then as teachers, is the foundation for understanding and teaching young people. Students live with the same contingency. The teacher’s goal is not to clean it all up for them. The universe is not transparent to our understanding. Education is not about making everything perfectly transparent to our students. Thoreau shows us how we can live boldly and deliberately and still hold this existential humility as the beginning of a kind of pedagogical humility, which, in our technocratic times, we also desperately need. It is easier to imagine how to teach students to express themselves and find themselves than it is to help them move with nimbleness and grace between their own experience and the things that are outside that experience—and understand why that should matter.

We rightly let students practice agency over and over, and we rightly celebrate their uniqueness and their experiments, but we owe them indications of the limits of their agency and an awareness of the constraints that define what our agency really is. We are helping students imagine a world in which they may need to give themselves over to something as much as, or more than, they need to learn to express themselves boldly. Students should listen to the world as well as to themselves. The interplay should be endless. It’s that interplay that’s unique to each student. Books about school, so often centered on teaching and learning, so often concerned with efficacy and efficiency, should not focus only on the dynamic of how a student learns new things inside their head but also how they are building relationships to many versions of the world outside their head, away from them. This is quiet moral work. It is also existential work. We might borrow language from Matthew B. Crawford’s first book and also call it soulcraft.

Crawford’s Shop Class as Soulcraft is a portrait of excellence achieved through giving yourself over to a discipline or a craft, through opening yourself to “being schooled” by a practice or an ideal external to you. Creativity, Crawford tells us, is “a by-product of mastery of the sort that is cultivated through long practice. It seems to be built up through submission.” As an example, he offers a quintessential artist: “The musician’s power of expression is founded upon a prior obedience; her musical agency is built up from an ongoing submission.” He goes on: “I believe the example of the musician sheds light on the basic character of human agency, namely, that it arises only within concrete limits that are not of our making.” Malcolm Gladwell popularized the idea that mastery of anything with any kind of complexity takes ten thousand hours of practice. Crawford makes sure we don’t see this as a simple transaction. We have to fully give ourselves over to something and be immersed in its contours and its constraints in order to demonstrate achievement and excellence.

The universe is not transparent to our understanding.

The point is not merely to establish the conditions for getting really good at something like music or writing or chess. The point, for anyone working with young people, is to recognize and leverage the relationship between unique individuals with their own aspirations, their own Genius, and the way those individuals develop and move toward anything. The easier choice would be to think of students as needing to release the vision they have for themselves. The ultimate aim of their education is to find what they want to do and then to do it. A simplification of Emerson and Thoreau could lead us in that direction—all wind to propel and no vessel to ride. The more complex choice would be to lead unique, individual students to develop a synergy with something that is not themselves. If you’re Thoreau’s pupil, this synergy could be with nature, but it could also be a tradition or a project, an idea or a craft, a community or a cause. But to achieve your meaning, you have to give yourself over to something that is not simply you. You participate in a larger project, a larger meaning. Crawford likes the language of submission and immersion. Emerson’s imagery is more euphoric, but the trajectory is the same: “Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm. The way of life is wonderful. It is by abandonment.”

The making of meaning, then, is not merely expressive. It is discovered, or, better, encountered, and when we encounter it, we abandon ourselves to it. I love pianist Jeremy Dink’s description of his early experience with the music of Mozart. “The growing, climbing notes were mapping onto me, everywhere, rising in my chest,” he writes. “I was no longer receiving music from without, but being filled from within.” That image of music mapping onto his twelve-year-old self is vivid, even startling—the Not You claiming and filling the You. In our progressive framework, we would default to saying that Dink developed a passion for Mozart, the agency all his.

“Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm. The way of life is wonderful. It is by abandonment.”

Returning to Thoreau, channeling his balance of self and world, I want to say that the only thing that matters in this process of flourishing through immersion in something outside you is choosing your own track, but even there I’m not sure. Is it always lesser to be inside a commitment that offers meaning without deciding for it? Is there a mode in which not having to constantly renew your choice for what you give yourself over to is liberating and life-giving? Is there a settled state in which we abide inside something—and that abiding lets us flourish? Do we always need to require of ourselves that we know exactly what we want and are aiming for and that we make that known to others? And how different is it to say (as I have many, many times), I want students to find themselves, to figure themselves out, and to live passionate lives, rather than saying, I hope my students are able to get into synergy with something outside the nutshell of their consciousness and then flourish in unique, or maybe not-so-unique ways? Is uniqueness even the necessary thing for flourishing?

Thoreau embodies that puzzle for me. He wrote one of the founding texts of American individualism and told us to get off the well-worn paths, but there he is hoeing his bean rows bare-footed to feel the earth better and paddling out to the middle of Walden Pond, almost, it seems, to lose himself in the mirrored play of sky and clouds and sun on the water, the fish looking like boats with sails, he tells us, in their reflection. Whitman celebrates himself and sings himself. Thoreau is too busy giving himself over to the ice and the woodchucks and the loons. He is a model of synergy more than non-conformity. He is, to quote Stanley Cavell again, “letting himself be read,” and not always insistently reading.

There is something in this for teachers to pay attention to. We are good at teaching students how to read the world and its various systems (languages, math, political structures). How might we organize school for students also to be read—and not by us—to be mapped onto? Because if all you do is read the world with confidence, you risk developing knowingness. But if you let yourself be read as well, and you submit yourself to what is for the moment beyond you, you give yourself a shot at wisdom, and also a kind of feeling for what the world might be in its relation to us.

I want to look out even further too, away from just individual students and their relationship to some discipline or idea or project, and think about how the You of the student relates to the Not You of the larger culture and the country and the past. Who could argue that we are not under enormous collective stress in both our small local communities and our large national ones? Schools are in the middle of that larger pressure and uncertainty. Older cultural understandings of the centrality of the individual are being challenged and redefined. A former narrative was that the point of an American life was to define your terms for yourself and to be left alone to be quirky and even antisocial as long as some basic commitments to the common good were honored: no yelling fire in crowded theaters, for example, and no willful libeling of another person. But we don’t trust that older narrative now, because in practice it leaves too many people out. Certain people get to raise a quirky voice, but others struggle to be heard at all. The ground beneath our feet, to think with Bugbee again, is neither level nor smooth. When we are born, we do not choose our terrain. It tilts us from the start, and it gives us the vantage points that shape our worldview, even if they don’t determine them. Our institutions tilt too, both left and right.

We are increasingly aware of the collective work needed to advance greater fairness, to account for experiences that aren’t our own, to rethink the general welfare, and to achieve a greater balance and mutual respect in spaces that we share. These cultural pressures have recalibrated some of our thinking about individualism. Our challenges now seem too vast and interconnected to celebrate our lonelier freedoms. The novelist Richard Powers promotes “kinship, connectivity, the relocation of meaning outward into a shared process of rehabilitation.” These are not a “set of sacrifices,” he notes, but a “joyful assertion of purpose.” We are a long way from the dilemma here of Augie March. Similarly, Ta-Nehisi Coates contrasts a “thin definition of freedom,” focused on blank-slate desire, with one “that experiences history, traditions, and struggle not as a burden, but as an anchor in a chaotic world.”

This heightened awareness of our shared life and our shared contexts is a healthy corrective to myths of lonely cowboys and self-made men. Since the pressures and new awarenesses outside our school walls always push inside, what new modes of teaching or of school will account for our evolving understanding of what it means to be an individual inside our social, political, and historical context? When we throw open our school doors for students, what world exactly are we releasing them into? Emerson’s world? James Baldwin’s? The Dalai Lama’s? Elon Musk’s? What have we painted the world to be, and how have we taught them to enter that world? For this is what schools do, too. We’re just not very good at describing the work we do this way. But it is the work, and that work is the illumination of the glorious You. Let them write their Song of Myself. And then the work is the clarity of the immensity that is Not You, only a fraction of which they’ll ever even encounter, much less comprehend. What song will they write about that?

The problem with the student-centered approach to school is that the students experiencing this framework might come to think of themselves as the center of their education, and then as a center in their lives. Told over and over to make their own choices and to write their own story, why wouldn’t they? But students are and are not that center. The paradox of their uniqueness on the one hand and their smallness on the other should haunt them. It should haunt their teachers too. A rich education should teach students to swing subtly and regularly between who and what they are and who and what they are not, between their interests and needs and the needs and realities of the larger world, between You and Not You. This is not just a right recognition of limitation but a healthy posture of openness to the world, a posture of receiving and responding and not just expressing and claiming. It provides equipment for healthy moral and civic life, as well as for a life adjusted to its conditions for its own sake. Without this shifting balance, without this movement back and forth, the progressive ideal of student-centeredness risks cultivating young people who need and expect the world to adjust to them, who struggle with the messiness of our life together and with the ultimate opacity and mystery of the world. The adults could probably stand to think more about the Not You as well.