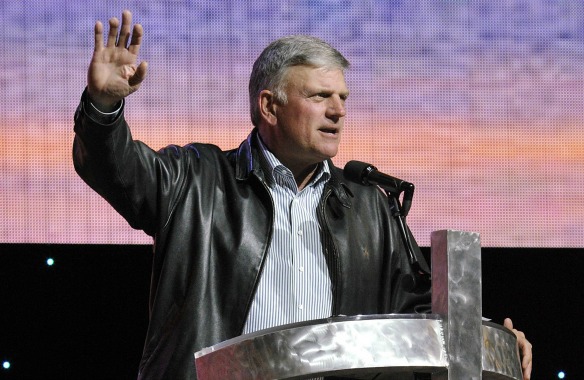

On June 5, Franklin Graham took to his Facebook page to provoke a boycott of Wells Fargo. The bank has released a series of nine new commercials profiling their customer diversity, including one featuring a lesbian couple learning sign language in advance of adopting a deaf child. Incensed at the “tide of moral decay that is being crammed down our throats,” Graham announced that the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, of which he is CEO and president, would be “moving our accounts from Wells Fargo to another bank.” He encouraged his Facebook followers to think of other pro-gay companies to boycott: “Let’s just stop doing business with those who promote sin and stand against Almighty God’s laws and His standards. Maybe if enough of us do this, it will get their attention. Share this if you agree.”

As of this writing—72 hours after that post—more than 90,000 people agreed. Rather, more than 90,000 people had clicked “Like” on the post, which is the most basic Facebook way of saying “I agree.” Nearly 41,000 had followed Graham’s instructions to “Share” the post onto their own pages. Both types of clicks register affirmation, and both drive more attention to Graham’s post—in Facebook’s system, any sort of user interaction can boost a post’s visibility.

At the risk of playing gotcha, it’s worth asking whether Graham’s boycott of pro-gay businesses will extend to Facebook. If so, he’ll need to delete his very successful page. In February 2014, the company added a “custom” option to the Gender field in profiles, and they’ve indicated their support of gay marriage on multiple occasions. Everyone who uses their Facebook profile does business with Facebook—indeed, users are the product Facebook sells, and users improve the product line and build Facebook’s advertising revenue with every post, every click, every moment of attention they give to the site. Thanks in no small part to people like Franklin Graham, Facebook’s business is very good.

Aside from the televangelists Joel Osteen and Joyce Meyer, Graham appears to be the most popular Christian leader on Facebook. In an era where Facebook has become a primary filter—in many cases, the primary filter—for what people pay attention to online, Graham is building a Facebook presence that surpasses every other vocal Christian leader in America. Graham wears multiple hats—he’s the president of the humanitarian organization Samaritan’s Purse in addition to the BGEA—but his Facebook page is mostly a fount of advocacy for his vintage Christian Right political worldview. Graham’s forbears, such as Jerry Falwell, would have salivated at the easy attention-gathering power of today’s social media platforms. Culture war leaders of yesteryear worked hard to gin up media attention, spinning out urgent press releases and offering inflammatory quotes on trending national news. Franklin Graham simply has to go to Facebook and fill out his answer to the status update box: “What have you been up to?”

Well, maybe not “simply.” Graham is winning at Facebook because he—along with, one presumes, his communications team—is smart about using Facebook.

At the height of his career, Billy Graham could speak to half a million people or more during a preaching crusade, though it often took several consecutive days of work. Thanks to Facebook, Franklin Graham can speak to that many people every day. Osteen and Meyer have more likes than Graham—10 million and nearly 9 million, respectively. The piety page Jesus Daily, which posts inspirational pictures and quotes, is even larger; its 26 million likes rank it among the most popular pages on all of Facebook. Jesus Daily is beating Kim Kardashian and Christina Aguilera, who have roughly 25 million each, though it is well behind Taylor Swift (71 million) and Shakira (100 million). Those are impressive numbers, especially compared to Franklin Graham’s 1.6 million likes. Yet in terms of actual visibility on Facebook day in, day out—in terms of gaming Facebook for peak user engagement around the clock—Graham is outgunning them all.

When I visited the page on June 5, 709,022 people were “Talking About” Graham’s Facebook page, about 45 percent of his total fans. The number of “People Talking About This” fluctuates, and I happened to check that stat at a high water mark—when it was buoyed by his bank boycott. But Graham’s figure is often strong: I’ve seen it go as high as 908,228, and never as low as 400,000 since I began paying close attention in April. The “Talking About” metric is a measurement of fan engagement—not “How many likes do you have?” but “How many people are interacting with your posts right now?” Joel Osteen’s number of likes is many times higher than Graham’s, but when I’ve looked a few times recently, only around 23 percent of those fans were talking about his page. At Joyce Meyer’s page, 17 percent of her fans were talking about her posts. Rick Warren? Nearly 2 million fans, but barely 1 percent of them are engaged. Graham is far and away the leader of the pack.

That’s in part because Graham gives his fans much more to talk about. He posts at least twice per day, nearly every day. The page is sprinkled with amusing personal miscellany—one recent post extols his Fitbit—and Christian quotes or Bible verses. He also reports occasionally on the vital aid work of Samaritan’s Purse and calls for prayer on widely felt tragedies. But most of Graham’s posts are conservative Christian hot takes on the news. This spring, he has touched on the Baltimore riots, Bruce Jenner (and, later, Caitlyn Jenner), Hillary Clinton’s cash, homosexuality, and militant Islam. Those last two subjects predominate. In all cases, his tone tends toward the visceral—appeals to emotion primed for clicks.

Consider this post from May 16: “Can you believe these idiots? Gender fluidity? Here’s an example of some of the wicked things misguided educators today want to expose our children to—look at this Fox News story. It should make your blood boil that they want to brainwash our children!” The post links to a Todd Starnes op-ed—not, nota bene, the same thing as a “story”—with the headline: “Call it ‘gender fluidity’: Schools to teach kids there’s no such thing as boys or girls.”

Or consider this post from May 28: “CNN reported today that scientists have discovered ancient jawbones and some teeth in Ethiopia that they say may shed new light on our earliest ancestors. If you really want to know where our earliest ancestors came from, check the original source, God’s Holy Word.”

Both posts are longer than the above quotes, though not much longer—Graham’s lengthiest Facebook posts hover around an economical 150 words. On Facebook, that’s enough material to proclaim a position and engender weeks of reaction. The comment threads on Graham’s posts can run on for weeks. The two posts above have (again, as of this writing) 10,654 and 5,198 comments, respectively, and are still active. The threads themselves are about what you’d expect if you’ve spent any time at all reading web article comments on religion and politics topics. Let the reader beware.

But constructive dialogue, of course, is not the goal of media strategies like Graham’s. The goal is attention. That’s what Franklin Graham and Facebook are winning together. Facebook has 1.4 billion users, and roughly half of them get their news from the site. More and more people are tuning into Facebook as a front page of world events and commentary. All sorts of media companies use Facebook, but the ones that perform best are the partisan outlets—conservative outlets like The Blaze, liberal outlets like Mother Jones. The same holds true for partisan persons like Franklin Graham.

Successful Facebook pages have a way of compromising one’s mission. Once you figure out what people click on, you start creating posts that get those clicks. There are a few tricks to the Facebook trade, and they’re fairly easy to reproduce. We’re awash in evidence of this today—it’s why so many web headlines sound the same; it’s why so many viral posts are viral in the same way; it’s why BuzzFeed works; it’s why Clickhole exists (and is necessary).

But if you’re committed to an editorial mission, or a political mission, or (to be sure) a religious mission, what works on Facebook may not be what’s best for that mission. Sure, you can figure out how to get clicks on Facebook. But is getting clicks on Facebook consistent with your larger purpose? Can you go viral repeatedly on Facebook and maintain your intellectual integrity? Can you go viral and still care for people—for the human beings who have lives beyond their Facebook user profiles? Once you have a smart Facebook strategy and a successful Facebook page, you tend to stop asking.

A question for Franklin Graham: Do you want to address the problem of radical Islam? Refusing to admit Muslims into the fabric of American life (as you do here and here) runs directly counter to that aim. Another: Are you serious about ensuring a place at the table for traditionalist Christian views on marriage? Rather than boycotting Wells Fargo into submission, it might be wise to build strategies for a true democratic pluralism that makes room for your perspective. Your Facebook speech acts are the inverse of real-world action that might protect and advance your views.

Graham is clearly—and rightly—concerned that his Christian worldview is on the wane in America. He also clearly—but wrongly—believes the wisest response is to fight for that worldview by lobbing truth bombs into the public square. That sort of approach is increasingly puzzling. Technologies like Facebook are laying the strategy bare. Full of sound and fury, it accomplishes nothing. Except sound and fury.

Think about the basic structure of a Facebook post on pages like Graham’s. Consider its potentiality as a cultural product. Graham shares his opinion. Maybe he asks a broad question or two, inviting response. That’s the full extent of his participation. He does not moderate the discussion. He does not try to win people over to his ideas. He certainly does not consider his interlocutor’s ideas and figure out how they might challenge his own, even for the purpose of improving his own position. His goal is not persuasion. It is not participation in a public discussion. The only goal is proclamation.

Like all of the big media that preceded it, Facebook turns out to do proclamation very well. This is what a successful Facebook strategy looks like for anyone nurturing a bully pulpit: Post your opinion. Make it as provocative as possible. Encourage people to like and share if they agree. What if they disagree? Or what if they agree but have some questions? No room for that. Due consideration is not a viral strategy. Proclamation is. Promote yourself. Get as much attention as possible. Ignore dissent. Reject intellectual modesty. Refuse charity. Assume the worst of your opponents.

Now, watch the likes roll in.

Franklin Graham is winning Facebook. But winning this game does not seem like a very Christian thing to do.

Patton Dodd is a writer and editor in Maryland.