Since 2020, celibacy has emerged as a formidable dating and romance trend, particularly for young women. Celebrities including Drew Barrymore, Julia Fox, Tiffany Haddish, and former Playboy model Jordan Emanuel have all come out of the woodwork to declare their abstinence, while women have posted Reddit screeds about the benefits of going without sex. In a 2024 review of a one-woman comedy show called Boysober, The New York Times declared celibacy “this year’s hottest mental health craze,” and this past June, memoirist Melissa Febos published a book about a self-imposed period of abstinence, called The Dry Season: A Memoir of Pleasure in a Year Without Sex.

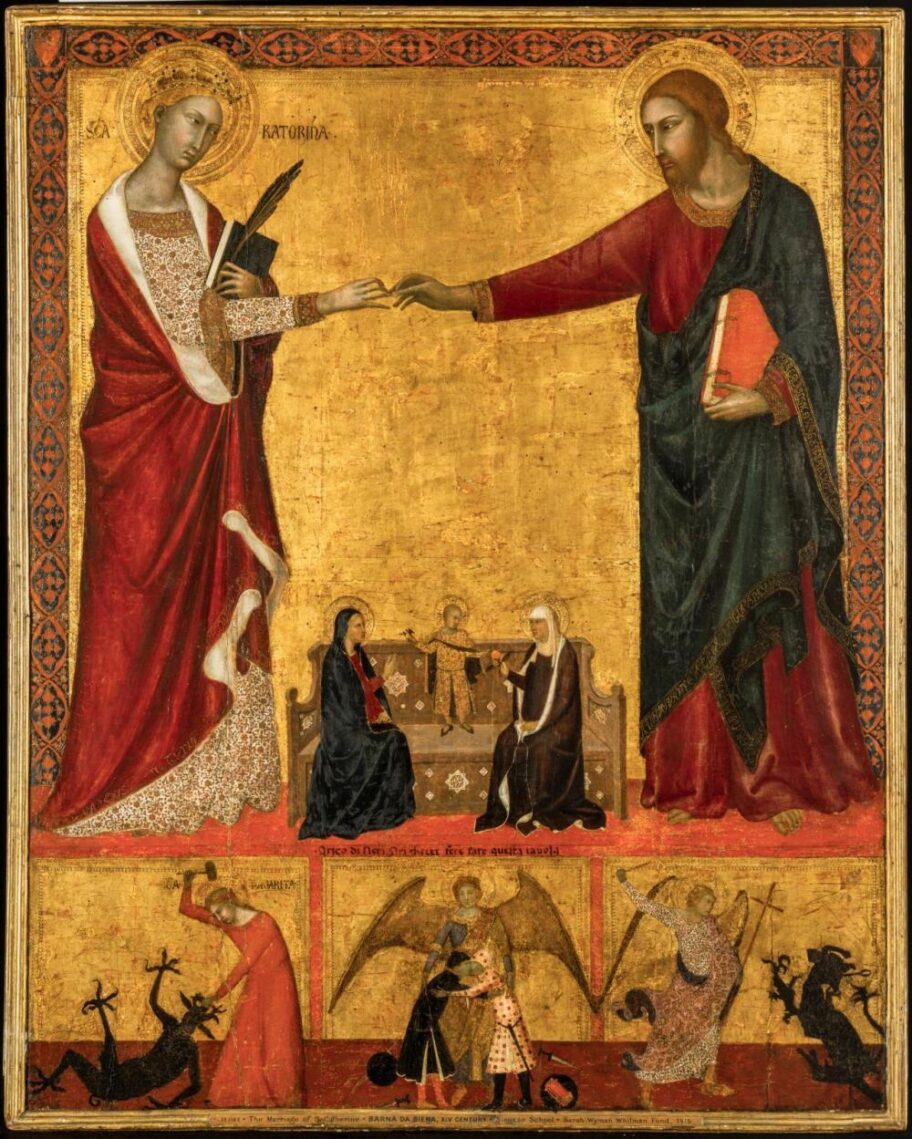

Though these women largely reject the idea that their abstinence has a basis in religion, when you hear the word “celibacy,” it’s hard not to immediately conjure up images of nuns. (Febos is explicitly religious in her allusions, citing Catherine of Siena, Hildegard of Bingen, and the Shakers.) In 2021, I was curious what a Catholic person with a deep personal connection to celibacy would think of this, so I reached out to Jenna Cooper, a “consecrated virgin” in the Catholic Church. A lesser-known “vocation” even amongst Catholics, consecrated virgins are what laypeople might think of as freelance nuns: they’re celibate, institutionally recognized for their piety, and often work for or within the Church, but they live outside convents or monasteries, can own property, and don’t usually dress distinctively. If “cloistered” nuns—those who live within monasteries and rarely, if ever, leave its walls—are often described as living a “hidden” life, consecrated virgins might be described as hiding in plain sight.

Jenna and I have enjoyed talking about faith in the modern age since that first discussion. Below, she gives her thoughts on the history of consecrated virginity, the theology of celibacy, and whether we’re seeing a rise of “radical traditional” Catholicism.

Kelsey Osgood: So let’s start with the most basic question of all: what is a consecrated virgin?

Jenna Cooper: In the Catholic Church, we have a long tradition of what we call consecrated life. A culturally familiar example of that would be nuns who teach in schools. At different points in history, different specific forms of consecrated life have evolved. Monasticism was a movement at a time in late antiquity; we have mendicant orders, like the Franciscans in the Middle Ages, who responded to a particular need. But consecrated virginity is actually the oldest form of consecrated life in the church. It’s the original form.

In the early church—when the apostles were still walking the earth, prior to 100 A.D.—we had women who felt called to be very radically dedicated to Jesus. At that point in time, women generally did not have a lot of rights. In the early Christian context, in the Jewish world, women had more rights than the pagan Romans did, but still, their identity and purpose were by and large defined by marrying a man and bearing children. So in the early Church, you had women who would renounce marriage for the sake of a deeper love of Christ, a greater dedication to service. We had both men and women who embraced celibacy, but women who did so were recognized as a particular class in the early Church. Our earliest reference to this is St. Ignatius of Antioch. In Letter to the Church at Smyrna, he greets them as “the ever-virgins called widows” (in Greek). So we see that there were women who committed to a life of virginity who were a distinct enough group that they could be recognized as such.

Eventually there was a liturgy that developed for solemnly consecrating women to a life of virginity. Our earliest written versions of that are from the 600s and 700s A.D., but St. Ambrose references his sister’s consecration as liturgy in his book, De Virginibus, which was written in the 300s. So if he’s referencing this like it’s no big deal, you know there must have been an earlier liturgy.

KO: Was there ever a period in history during which consecrated virginity fell out of favor, or played a lesser role in the church functioning generally?

JC: In consecrated life, we talk about charisms, a Greek word meaning gift. So a charism is a gift directly from God given to people for the wider church. But we also have a hierarchical dimension of the church. We have a governing dimension that’s much more human; we have our own system of law, canon law, and we definitely respect the appropriate role of law in the spiritual life of Catholics. Throughout the church’s history, there’s been a balance—one could call it a dance—between charismatic dimensions of consecrated life versus the more hierarchical government dimension. It’s God inspiring people, and then also the successors to Jesus and the Apostles governing and guiding. You don’t want to get too heavy-handed in one direction or the other.

So with consecrated life, we have these inspirations, but they’ve also been confirmed over the years. In the early Church, we did not have the infrastructure. We were a persecuted minority. We didn’t have land or institutions. So it was much more ad hoc: you’re a woman, you embrace this call, you live on your own or with family or with other consecrated virgins, somewhat informally. But after Christians stopped being martyred routinely, there was a different kind of overlapping movement of people who’d go off into the desert and live a very ascetical, demanding, sacrificial life. That was like white martyrdom.

Eventually, monastic life developed more formally. St. Benedict, who was originally a hermit, wrote a “rule” codifying his more balanced way of living this ascetical life. Many monasteries still follow it today. With consecrated virgins specifically, we had this canonical category, and we also had a liturgy, a ritual for entering into this consecrated state. But once we had monastic life in late antiquity, more women started entering organized communities, for the sake of a well-balanced spirituality and also maybe for protection from societal violence.

Eventually, things started to shift to the point where it wasn’t that an already-consecrated virgin would enter a monastery and make monastic vows and promise to follow their rule, but rather a woman would enter a monastery, make all her vows, promise to follow their rule, and then receive the liturgy for being a consecrated virgin, so you have almost overlapping forms of consecrated life.

KO: So because there was this form of consecrated life that had all these other benefits, or that was institutionalized in a way that felt appropriate for the time, that meant there were fewer of what we might think of as consecrated virgins today?

JC: It’s almost like how you have fewer women who are solely housewives today. It doesn’t mean you can’t be a housewife. It’s just not as common. I think it was more cultural forces as opposed to people sitting down and saying, “We’re going to make this decision that you can’t do this.” Also, different time periods have their different biases, so people aren’t necessarily going to categorize things in the moment the way we are looking back historically, if that makes sense. So if you receive the ritual for becoming a consecrated virgin, you were a consecrated virgin. Maybe you’re also a nun. Maybe you are living outside a monastery. But for a variety of reasons, eventually society became more nun-heavy and had fewer women who are consecrated living outside monasteries as a general practice.

In the middle ages, consecrated women were pretty much strictly cloistered. Even lay women really didn’t go out much. Occasionally, there were different movements of women who weren’t living in monasteries. They were maybe spiritually attached to a religious order and made private vows. We have some saints who did that, like Catherine of Siena. There were anchoresses, like Julian of Norwich. So you have outliers. But by the middle ages, the dominant form of consecrated life by far, if you’re a woman and you wanted to give your life entirely to God, was being a nun.

A lot of things we think about as being very characteristic of cloistered nuns actually have their roots in consecrated virginity, like receiving a veil when you make your vows. Consecrated virgins receive a veil as a signifier of marriage, essentially. Some religious orders, like the Poor Clares, their spirituality, it’s very bridal. So those are definitely echoes of this particular vocation that they borrowed, which is entirely legitimate in the life of the church. But again, you’re a nun, you were part of this religious community, you’re following a specific rule, you’re not going outside of your monastery at all: these are things that distinguish monastic life from consecrated virginity as we conceive of it today.

KO: When did this start to shift?

JC: In the early modern era, beginning around the sixteenth century, there was a revived interest in women who aren’t strictly cloistered and go out and do works of charity. So for example, the Daughters of Charity: Vincent de Paul founded this order to be dedicated to helping the poor, but you can’t do that if you’re locked behind walls. So then you start to see what we call apostolic religious sisters, who are not nuns and don’t make solemn vows.

Then in the 1960s, we had an ecumenical council, which is a meeting of bishops from around the world who, with the pope, clarify points of Catholic doctrine, during which they talked a lot about the church’s self-understanding and our own internal structure. Also at the time, there was a great interest in the theological concept of Ressourcement, which means going back to the original sources. How did we pray in the first few centuries? A lot of customs accrued in the Middle Ages, but were those essential or are they not culturally relevant anymore? That’s when there was an interest in restoring some of these ancient forms of life.

We looked back to this order of consecrated virgins, and that was actually brought back. The ritual for consecrated virgin was continually in use because a few religious orders, like the Carthusians, as well as some Benedictine monasteries, kept using it as a custom for the solemnly professed nuns. The rite that was in use in some of these religious orders was revised as well, so that there were now two versions, one for nuns and one for women living outside of monasteries. This revision was formalized in 1970, and it de facto revived this form of consecrated life.

Another interesting feature of this is that religious communities exist sort of apart from our “normal” Catholic church structure. So the Catholic church is very geographical. The pope is the bishop of Rome, and then you have all these bishops of local areas called dioceses. We call them “local churches.” If you read the New Testament, and you see St. Paul’s writing to the Corinthians, that’s almost a proto-diocese. But you didn’t really have a way for women to belong to a diocese in their consecrated life. If a man wants to be a priest, he can join a religious order like the Franciscans and be a Franciscan priest, or he can approach the bishop of the local diocese and be a diocesan priest. When consecrated virginity was revived, there became a very explicit role for women attached to this local church. Just for the sake of balance, it’s a feminine presence that was there with religious orders, but not with this official structural connection.

KO: Tell me why celibacy, or why virginity, is so crucial to this form of consecrated life.

JC: I’m probably over-answering things. I’m a canon lawyer and I can’t help myself!

In Catholic canon law and our official terminology, celibacy means not being married in the normal way to a mortal spouse. If you’re married to Jesus, he’s truly a spouse in a sense. That sounds really intense, but that’s the best phrasing I can come up with. So if you are not married in the normal way to a mortal spouse, that’s celibacy. We also talk about continence, which is not engaging in any physical sexual acts. Chastity is behaving in sexually appropriate ways for your state in life. So if you are intimate with your spouse, you’re being chaste. But if you’re not married, you’re not supposed to be intimate physically with anybody. We talk in consecrated life about chastity, but that’s sort of poetic, like super-chastity. Literally being a virgin, that’s unique to this specific state of life. So if you are a woman and you’ve been married and you’re widowed now, or you had some degree of intimacy with a former boyfriend, you can enter a religious community, because the vows you make as a nun, that’s from this point forward. For consecrated virgins though, you’re literally a virgin.

For consecrated virgins, it’s sort of like stating publicly, “I’m persevering in this way of life now for a higher, more focused purpose.” It’s a little bit of a different framing. But what also gets misunderstood, even among women thinking of consecrated virginity and even among Catholics, is that we don’t have a very in-depth definition of what that means in the nitty-gritty details. The church is never going to answer how far is too far. So to be a consecrated virgin today in our modern current law, the standard is you’ve never been married or engaged in “public or manifest violations of chastity.” You’ve never cohabitated with a boyfriend, let’s say. Other sins against chastity, that’s sort of left to personal discernment.

For consecrated virgins, it’s sort of like stating publicly, “I’m persevering in this way of life now for a higher, more focused purpose.”

KO: So it’s a little blurry. If you had a high school boyfriend and you made out with him, we’re not quite sure where that lands.

JC: Yes. The fundamental question is, can you embrace a charism of virginity in clear conscience and with psychological equilibrium? People get really focused on the blurry areas, but I don’t think that’s helpful, because this stuff is so personal. But also, it’s important to note that a woman can’t lose her virginity because somebody’s taken it. You lose your virginity when you make a choice in freedom with full knowledge. So a woman who was a virgin who was raped wouldn’t be considered a non-virgin, for example. I feel like that’s a healthy message to the modern world, that women are defined by our virtuous choices and not by what other people may have done to us.

Catholics really do believe that if you are physically intimate with a person, you’re sharing a very deep part of yourself. Sex is never casual or meaningless for Catholics. Giving yourself in marriage is a good and holy thing. So the idea behind consecrated virginity isn’t just that, okay, I’m walled off and that’s it. You’re not giving yourself to a lesser good, because you’re giving yourself to a higher good. You’re saving yourself entirely for God. It’s purity not in the sense of like, “Oh, I’ve dotted all the i’s and crossed all the t’s and I’m perfect.” It is not these reductive notions. It’s purity in the sense that it’s very focused. I think that’s very powerful.

I think even secular women, if you’re being intimate with lots of men and having lots of meaningless encounters, that’s dissipating. I think that’s becoming our cultural common sense.

Consecrated virginity is sort of that same insight, but in an exponential way. Again, the spirituality is, you’re giving your entire self to the Lord, all your faculties, all the room in your heart. But I think even on a more human level, it does say something about women’s value as people. We have dignity, and we can offer ourselves freely to the Lord as a higher purpose.

In Catholic theology, there are a lot of other relevant theological principles. For example, in the ritual for consecration, it talks about the Church as virgin, keeping the faith “whole and entire.” We’re keeping our truths and our doctrines undiluted and not softened by the spirit of the age or the whims of culture. It’s this firmness of purpose.

KO: So a consecrated virgin embodies that same idea?

JC: Yes, virginity is embodying that specific aspect of the church. Also, Adam and Eve were traditionally virgins before the fall. So it’s a reflection of that original innocence of humanity. Another connection: in Mark 12, Jesus is asked about a woman who had seven husbands—who’s going to be her husband in the next life? I’m paraphrasing here, but Jesus says that’s not the right question to be asking, because in heaven, people will be like angels, and there’s no marrying or giving in marriage. We would see that as a mysterious glimpse into the life of the world to come. So virginity specifically is an especially strong sign of what we are anticipating as life in heaven.

That certainly doesn’t mean that I’m exempt from all the trials of life in this fallen world. And again, we as Catholics are very pro-marriage and pro-family. But there’s a line from the consecration ritual that talks about consecrated virgins forsaking marriage for the sake of the love for which it is a sign. Marriage and family life: it’s very connected with this temporal, passing world, but it nonetheless represents something much higher, and consecrated virgins are skipping over that to go right to what we believe life in heaven is essentially.

KO: It reminds me a little bit of how on Yom Kippur, Jews don’t eat and don’t drink, but we also wear white and are forbidden to have sex. And even though a lot of people outside of the Jewish world think it’s a day of mourning, it’s ideally supposed to be a chance to manifest an angelic nature, and to be needless and transcendent in a way that we don’t experience in our usual lives. It’s not morbid, even though it sounds morbid; it’s supposed to be elevating.

JC: I think that’s a very good parallel, actually. It’s that same idea of being set apart from the mundane. Again, there’s going to be different nuances. And obviously, if this is your whole life, you can’t do it on the same level of Yom Kippur. For the virginity aspect, there is an element of the penitential. It is a sacrifice, but I embrace this as a primarily joyful thing.

KO: Does the celibacy of consecrated virgins parallel the celibacy of priests?

JC: The idea of women renouncing marriage to be more dedicated to God, it has a very heavy spousal dimension. So the way I usually describe it in pastoral situations to lay people, not scholars or canon lawyers, is that all the room in your heart you would have given to a husband and children you offered to the Lord. And when you offer that to the Lord, you also serve his people. So very early on, consecrated virgins were given the title Bride of Christ, Sponsa Christi. That can be kind of a challenging spirituality for the modern world—to pick just one reason, it might be hard to conceive of a “spousal” relationship that isn’t erotic or sexual—but there are a lot of very beautiful theological implications. For example, there was a document in 2018 called Ecclesiae Sponsae Imago on consecrated virgins and our way of life. And that literally translates to “image of the church as bride.” So we’re an image of the Church’s theological nature.

There are a lot of debates about how the Catholic Church has an all-male priesthood, and what does that mean for the dignity of women? There’s a lot of theology on this, but one major theme is the idea that men as priests can be a clearer reflection of Christ, who was incarnate as a man. By limiting the role of priesthood to men, the Church is following the precedent set by Jesus when he personally walked the earth, since he only called men to be the twelve apostles. We don’t have official teaching as to why Jesus made that particular choice, but the most commonly proposed theological explanation is the idea that men can “image” Jesus incarnate as a man. So even though women aren’t ministerial priests, there is still a complementary state of life in the church that mirrors that in the form of consecrated virginity.

KO: I first reached out to you because I wanted to know if you had heard that celibacy was trending and what you made of that. And to my recollection, you were not aware that this was a phenomenon.

JC: I don’t think I was.

KO: So what do you make of the fact that celibacy is having this moment of mainstream recognition, albeit primarily not through a religious lens, and even sometimes the people who are practicing it are really vociferously rejecting any religious connection?

JC: I’m not as up on celibacy as trending. I think when you first asked me about that, it was almost about whether this is disrespectful or akin to cultural appropriation. There are certain things that are Catholic-specific. If you are not Catholic and you’re eating meat on a Friday during Lent, we don’t really care. You’re not Catholic, you’re not bound to this. But there are some Catholic teachings that we do believe are just basic human things. Don’t kill people: that’s basic Catholic teaching, but we don’t think anyone should murder anybody else. So with marriage and family life, we don’t think that it’s healthy or good for anybody to be physically intimate with somebody they’re not married to. So my take is that even if you’re being chaste for purely secular reasons, that’s just basic human virtue, and it’s going to be not only in accord with God’s will but also conducive to human flourishing. I think it’s good if you get to a virtuous path, even if it’s not the theologically best path. But if somebody decides not to murder somebody for purely secular reasons, I’m not going to quibble about like, Wow, did you really do this from the proper theological standpoint? No, somebody’s not getting murdered. That’s great.

I think it gets a bit more complicated if women are embracing celibacy for very secular reasons and quoting our Catholic saints out of context or misunderstanding what female mystics or saints were trying to do in their pursuit of celibacy. Because then you’re misunderstanding our own tradition. I think that gets to be a little bit more like cultural appropriation.

KO: Tell me how you ended up a consecrated virgin. When did you first feel an interest in pursuing a consecrated life?

JC: I was raised in a Catholic family. I went to Catholic grade school. We went to Mass every Sunday. This was my world from the beginning. My parents taught us how to pray when we were young, and I just always really took to it. When I was twelve, my prayer life deepened in a very radical way. I just fell in love with God, completely. And I remember thinking, “There’s nobody else who could compete with Jesus.” I just couldn’t imagine anyone more worthy of my love and my life.

When I was a teenager, I assumed I’d become a nun. This was the early 2000s, so you didn’t have sisters teaching in schools like my parents had, so I didn’t really have a lot of examples of consecrated life in my daily life. But when I was eighteen, I decided to find out more, because I really wanted to give my life to the Lord. And I started visiting different communities. I did visit some cloistered monasteries. I thought about that pretty seriously. But it just didn’t seem to fit the exact way I felt called. That’s a little bit hard to explain if you haven’t experienced it. But there was always this sense of something missing.

In many religious communities, the thing that was front and central was not the spousal relationship with Christ. That was something that really attracted me specifically. The idea of belonging to a local diocese, that was also a really important thing for me.

In a lot of religious orders and communities, you’re following a particular saint and their very specific traditions. St. Francis is a great saint, but I just didn’t see myself as a Franciscan. St. Dominic’s a great saint, but I just didn’t see myself as a daughter of St. Dominic. But I was really very inspired by the example of our early virgin saints, especially our virgin martyr saints like St. Agnes. You have these very young women who were very courageous, and there were stories about how these teenage girls faced their martyrdom more bravely than grown men, and their witness converted a lot of pagans. That courage and the intensity of that love was very inspiring to me. So I remember thinking, “Oh, I wish they could be like my sisters.” I didn’t realize consecrated virginity had been revived as a form of life when I was first looking into this. And even way before I was actually a canon lawyer, I was interested in reading canon law, and I found out you could still do this.

KO: You found out from reading canon law?

JC: I did, when I was nineteen. This was around 2004. A priest I knew, he asked if I would be interested in reading the part of canon law on consecrated life. And I said, yeah, that sounds awesome. Again, this is Catholic geekiness that’s on its own level, and I own that. Anyway, I was reading the relevant portions, and I had this inkling of, I think this might be it. And then I got a copy of the ritual and I was able to read it, and everything in this ritual just spoke exactly to the way I felt called in the depths of my heart. And then I approached my local diocese and there were a couple years of discussion. I was on the more unusually young end of this. I was twenty-three when I was consecrated in 2009.

KO: Tell me a little about your work as a canon lawyer.

JC: In the instruction that came out in 2018, it does talk about academic theological formation for consecrated virgins, and it does encourage consecrated virgisn to do formal academic programs according to your aptitude and what’s available. Not necessarily everyone’s getting a master’s degree, but it does encourage that. The text implies that if you’re not doing a formal program, you’d better have a serious reading list with, like, a mentor who can study theology, ethics, philosophy, and so on with you. If a man becomes a priest, he has to do four to six years of seminary and actually get a theology degree before he can become a priest. That has not traditionally been a requirement for women in consecrated life. If you’re a nun, you don’t necessarily have any theology, but this is requiring consecrated virgins to have something like that. My Christian feminist self loves this. Not only are we encouraging women to develop their intellectual talents, we’re mandating it.

I was consecrated way before this came out, but I was always an intellectually oriented person. I started my undergraduate career in art school, so I have three quarters of a B.F.A., actually. But when I was in the middle of discerning my vocation, I really thought I wanted to get into academic theology, and ideally, in the Catholic tradition, before you start doing graduate work in theology, you want to have undergraduate work in philosophy, because you need to learn how to think before you can start thinking about God. So I transferred to Seton Hall in New Jersey and afterwards went straight to a master’s in theology.

Canon law is the Catholic Church’s internal legal system. And that’s usually three years. I went to Rome and studied at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross. So my education is very, very similar to what a priest would get, actually. That is more intense than I think the church envisions for every consecrated virgin, though.

In my day job, I’m a judge in a marriage tribunal. I definitely see this as the apostolic activity my vocation calls me to. Consecrated virgins are supposed to be dedicated to the service of the church. We don’t have a specific means of service for everyone. You know, religious communities sometimes will have one specific thing that they do, like the Sisters of Life work for pro-life causes. But the church really does envision a consecrated virgin’s role as a very specific thing she would discern with her bishop. Certainly not every canon lawyer is a consecrated virgin and vice versa, but I do feel like this expresses my call to service, so my life is very integrated in that way.

KO: Are there spiritual requirements or obligations for consecrated virgins?

JC: Consecrated virgins, our “work” that we do is primarily prayer. So insofar as it’s possible for where we’re located, we’re supposed to go to daily Mass. We also pray the Liturgy of the Hours. So that’s Psalms, mostly, and some other prayers that are set for certain times of the day. And we’re also called to some sort of private prayer, just on your own talking to God every day. And different kinds of consecrated virgins do that in very specific, different ways. We’re also called to solitude and silence. So we don’t have to live alone, but a lot of us do. It’s actually a very instinctive thing. Every consecrated virgin I know, even if we’re totally different people, we all have this draw to silence. If we do have gatherings where we get together, it’s almost like, “It’s so good to see you and I’m having so much fun talking, but I need to stop talking to everyone right now.”

But even consecrated virgins I would not think are introverts, when they’re consecrated, they’re all of a sudden drawn to silence. It’s not a major discipline thing that I need to have times of silence. It’s very natural, but it is something that we’re called to foster in our lives.

Finally, the life involves some sort of penitential practice. Individually, you work out what that is with your spiritual director, what’s going to be healthy for you. So for me personally, I abstain totally from alcohol, and I also don’t eat red meat.

KO: There’s been a lot in the mainstream press, particularly in the last few years, about the rise of traditional Catholicism, or radical traditional Catholicism, it’s sometimes called. I’m wondering if you see a resurgence and what, if anything, you make of that.

JC: You need to parse out exactly what you mean by “traditional Catholicism.” Are we talking about a schismatic group that’s only using the 1962 Missal and is not listening to the pope? Or younger people liking traditional Gregorian chant but attending the regular normal Mass we have? I think the aesthetics these days are leaning much more towards the traditional, and also that we’re just doing more Catholic things like praying the rosary more often. Some of what I think outsiders looking in would see as more traditional practice is just more people taking their faith more seriously.

What is interesting with consecrated virgins is that even though Bride of Christ imagery is what some people would consider very traditional, because that was more common with nuns pre–Vatican II, you can only be a consecrated virgin outside of a monastery because the Second Vatican Council happened. So this is a very modern Vatican II sort of vocation. So we don’t really fit into Catholic culture war categories that way. Which I don’t think is necessarily a bad thing.

KO: What is the state of consecrated virginity today?

JC: Being a consecrated virgin was not even a well-known option among Catholics at the time that I was consecrated. Now, many more women are interested in this. It’s not hundreds of women every year trying to do this in every diocese, but I remember back when I was consecrated, you knew almost every consecrated virgin in the United States, or you knew of them, or at least you knew the name. Now somebody’s like, “Do you know so-and-so? She’s a consecrated virgin.” I’m like, “I’ve never heard of her!” Most dioceses will have at least a few now. It is an exciting time. It is a little nerve-racking, because we’re still trying to figure out the best practices. Back when I was consecrated, you had to be unusually dedicated to rooting out information on this. If you were a consecrated virgin before 2015, you really had a super strong sense of call, you really were going against the tide and you wanted to do this. Whereas now—and I think this is a good thing—more women know this is an option. Now there’s more of a need for more organized formation programs. How do you teach somebody how to live this life? I think that’s a challenge that we’re facing.

One of my hobbyhorses is, if you have these women who are dedicated, how do you make the best use of their gifts? I mean, not in a utilitarian way, but how do you highlight the gift of this to the local, normal people in the pews? How are you enabling people to best express this vocation in practical ways? I think that’s the challenge we’re seeing now. But it’s certainly an unexpected joy that this is becoming more popular.