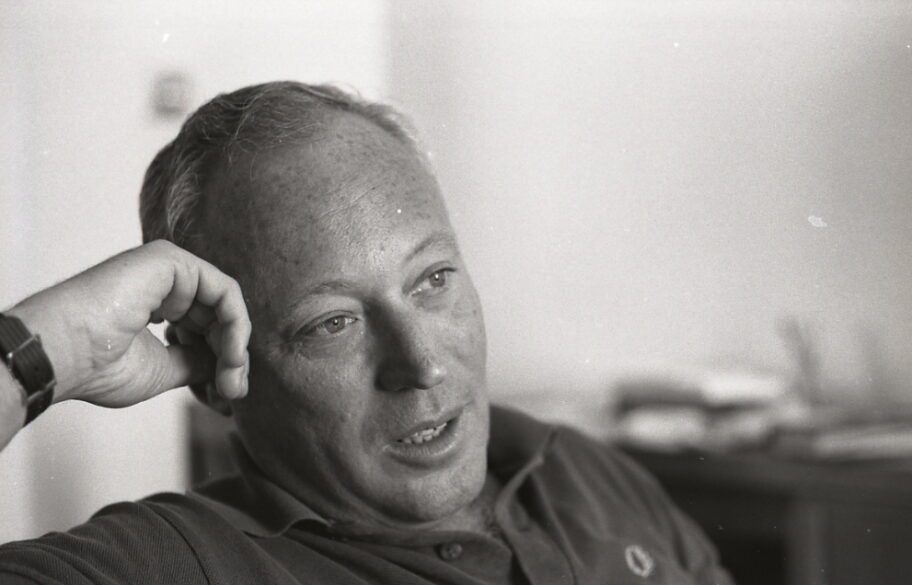

Solace comes from strange places. In the wake of the Oct. 7 attack on Israel by Hamas, I found mine in a once-famous novelist who sold millions of books in the 1960s but is largely forgotten today, a hyper-Zionist whose romantic views of Israel bear little resemblance to the grim realities of today: Leon Uris.

Uris is the author of Exodus, the turgid melodrama about Israel’s founding. At the height of its popularity in 1959, the novel sold 2,500 copies per day—and has sold an estimated 5.4 million copies to date. In the 1960 film version, Paul Newman played hero Ari Ben Canaan, a Zionist guerilla. The role of his love interest, the nurse Kitty Fremont, belonged to Eve Marie Saint. The promotional poster showed flames, presumably representing the Holocaust. From the fire rises a single hand clutching a rifle. It’s not subtle stuff, either on the screen or on the page. It isn’t supposed to be.

“He was the most important Jewish novelist,” Stephen J. Whitfield, a scholar of American culture at Brandeis told me. Uris was writing during the great explosion of middlebrow culture, as famously derided by the critic Dwight Macdonald in his essay “Masscult and Midcult.” Television was still something of a novelty, and though radios were everywhere, reading was a primary form of daily entertainment for millions of Americans. Exodus was pop, but it was also an act of nation-building, not unlike that which Stephen Dedalus vows to accomplish at the end of James Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man.

No, I am not comparing Uris to Joyce. Uris was not literary. His characters are flat, his plots schematic. His sensitivities are steadfastly blinkered; his politics are obvious and crude. And yet despite all that (or maybe because of it?), he could tell stories that riveted millions, stories that have outlasted far superior novels. Exodus “genuinely awakened among American Jews, and some others, feelings for Israel that they probably didn’t even know they had,” Whitfield said.

For many readers, the novel amounted to their first contact with Israel’s founding myth. “We forget how much mystery there was around Jews and Judaism,” says Rachel Gordan, a professor at the University of Florida and the author of Postwar Stories: How Books Made Judaism American. Exodus is one of the great branding exercises in modern literature, evoking pity for the victims of the Holocaust—portrayed most vividly by Dov Landau, a child survivor of Auschwitz when the story opens at a detention center on Cyprus—and awe at how those same victims could forge a nation of their own in hostile territory. By the end of Exodus, Landau is a seasoned fighter. Homeless at first, he is now an Israeli.

Time passed. Israel won wars, claimed territory and, in doing so, squandered whatever affection it had managed to earn from what we today grandly call the international community. As for Exodus, it retreated from relevance. It became an artifact, a creased paperback edition on my great aunt’s sparse bookshelf in Middle Village, Queens. In my younger years, I no more wanted to crack open her copy than to eat her kishkes (cow guts), even if they were from the best butcher on Queens Boulevard. Not me, sophisticated me, who read Saul Bellow or Philip Roth—writers of whom Dwight Macdonald would heartily approve—and who could do entire scenes from Woody Allen’s Manhattan by memory (“New York was his town…”). I, an acculturated American, who was Jewish but not Jewish like that.

Well, I still don’t like kishkes, and the kosher butchery on Queens Boulevard is now probably a Starbucks, but my views on Uris have, rather surprisingly and drastically, changed.

I have read not only Exodus, but the two other novels Uris wrote explicitly about the travails of the Jews: Mila 18 (1961), about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, and Mitla Pass (1988), about the Suez Crisis of 1956. Together, this triumvirate pretty much spans the Jewish experience of the twentieth century, from the shtetls of Russia to the killing fields of Poland and, finally, to the sands of the Sinai Desert.

It had never occurred to me to read any of these books, let alone all three. But as my social media feed filled first with images of burning kibbutzim in southern Israel and then flattened buildings in Gaza City, I needed something other than the daily barrage of depressing, enraging, and confusing news.

I wanted to understand Israel as it had once been understood, before Benjamin Netanyahu, before the nation of kibbutzim became a nation of settlements, before American evangelicals embraced it for messianic reasons of their own, before we were told to go back to Poland. I understood why Israelis were fighting now. I wanted to understand what they were fighting for then, when there was no Israel to speak of. I wanted to understand Israel as Uris wanted it to be understood, however flawed that understanding would later turn out to be. I mean, isn’t that what reading books is for—to escape into worlds other than you own?

My reasoning wasn’t just political. By 2023, I was exhausted by modern fiction, which seems to me to have gone plotless and banal, whether in the hands of rhetorical socialists (Sally Rooney), wan observers (Rachel Cusk), or edgelord provocateurs (Tony Tulathimutte). If these were the heirs to postwar highbrows, if these were Roths and Bellows of this century, then maybe it was time to give Uris a shot.

For many readers, the novel amounted to their first contact with Israel’s founding myth.

Uris fought in World War II, as a Marine. His experiences in the South Pacific form the basis of his first novel, Battle Cry. Before turning to Israel, he had written the screenplay for Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. “It was very instrumental in shaping how he conceived what a novel should be,” Uris biographer Ira B. Nadell told me. Exodus is essentially a Western set in the Levant.

By pivoting from war to westerns to Israel’s founding, Uris implicitly answered the question of why, and for whom, American troops had fought in Normandy and Sicily. Who were the walking skeletons the troops of the 4th Armored Division had seen when they liberated the Ohrdurf concentration camp? Where had they come from, and where would they go?

These were the questions he answered with his saga about a ship full of Holocaust refugees—a creaking Greek craft renamed the Exodus—trying to get to Palestine, which was then controlled by the British, who restricted Jewish immigration in order not to upset a wary Arab population.

Uris shamelessly cranks up the melodrama—then cranks it up some more. “That decision, that horrible decision he had made so long ago was coming back to haunt him now,” thinks a British official with a secret Jewish past. You know perfectly well that he is going to ultimately betray his duty and help the Jews yearning to disembark. Uris telegraphs all his punches. Yet somehow, he manages to land them.

Or, as the legendary journalist Pete Hamill put it in a review of Trinity (about the Irish Troubles—another Uris hobbyhorse), “Uris is certainly not as good a writer as Pynchon or Barthelme or Nabokov; but he is a better storyteller.”

When he set out to write Exodus, Uris “knew nothing about Israel, and he knew next to nothing about Judaism,” says Nadell. That may explain why portions of the novel are unabashedly didactic, as if the author were an eager student trying to show off how much he’d managed to learn the night before the exam: “The Russian Army entered Auschwitz and Birkenau and liberated them.”

He knew as little about Arabs, and cared much less. Writing recently in Vox, Marjorie Ingall—who “devoured” the book as a tween—called Uris out for his “rabid anti-Arab prejudice,” noting that most Arabs in Exodus are “evil cartoons,” in contrast to the “wholly noble” Jews who simply want their land back. That this project required the often violent displacement of Palestinians does not even merit lip service.

Time passed. Israel won wars, claimed territory and, in doing so, squandered whatever affection it had managed to earn from what we today grandly call the international community.

Mila 18, Uris’s novel about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, was published in 1961, the year Israel tried and hanged Nazi henchman Adolf Eichmann. The Holocaust reentered the public consciousness, more vivid now than it had been in the postwar years. The story of a Masada-like uprising in the rubble of Warsaw liberated Uris from the weightier responsibility of telling the entire history of the Jews.

Here, the writing is crisper, the plot more fleet: “Warsaw gagged. Clouds of smoke billowed from the ground and then rained down a billion bits of dust and ground-up brick and mortar. An unearthly silence mingled with the fumes of war.”

Fame was not kind to Uris. He was a hard drinker and drug user. At his home in Aspen, “marijuana brownies would regularly be served, sometimes unknowingly, to dinner guests,” writes Nadell in Leon Uris: Life of a Best Seller. It was in Aspen, too, that his second wife killed herself about six months into their marriage. By the 1970s, his novels were predictable, adhering to a formula of which critics (and readers) were growing tired.

In 1985, Uris wrote a letter to Whitfield, the Brandeis historian. Reflecting on Exodus, he noted that the book’s “most powerful impact” was “on the Russian Jews,” who read samizdat versions of the novel. Nearly four decades later, Whitfield says that assessment remains accurate. “Nobody could have imagined those feelings were there,” he said, among Jews whose identity had been effaced by the Soviet Union. “They were supposed to be extinguished.”

My family was among these Russian Jews. Though we escaped from Leningrad in the late 1980s to the United States, other family members went to Israel: on Oct. 7, some of the Hamas rockets fell on Ashdod, where relatives live in a large Russian community. One childhood friend joined the Israeli Defense Forces after college, recently completing reserve duty in Gaza. The proximity of danger has led many of my fellow Soviet emigres into the trap of uncritical boosterism, as if deprivation were justification.

But Uris wasn’t writing for this moment, and in any event it would be a mistake to see Exodus as a by-any-means necessary justification of Israel’s militarism. He had his blind spots, and if he was mostly indifferent to the Palestinians’ plight, he nevertheless understood that resolution required more than just force.

In the final scene of Exodus, Dov learns that his lover, Karen, whom he intends to marry, has been murdered by fedayeen in a cross-border raid from Gaza. The killing is based on a real episode that took place at Nahal Oz, one of the kibbutzim that would be attacked on Oct. 7. Many years before, in 1956, a young kibbutz guard named Ro’i Rotberg was killed there by militants from Gaza. Uris happened to be on the scene. So, remarkably, was Moshe Dayan, the revered Israeli general, who delivered a eulogy that is cited to this day.

In the novel, Karen is killed just as the main characters are about to sit down for the Passover Seder—a classic Uris move. Dov is devastated, but he also knows that answering violence with violence will solve nothing. “I cannot hate them …. we can never win by hating them,” he says. Whatever his faults as a novelist, Uris got that right.