On December 10 of this past year, President Obama signed into law the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). The ESSA replaces the increasingly unpopular No Child Left Behind Act, which drew ire for its emphasis on standardized testing as a measure of school performance. Critics objected to the loss of local authority over teaching standards, as well as the heavy-handedness of federal guidelines. The new law addresses many of these criticisms, giving states more autonomy in education policy. The ESSA passed the House and Senate with overwhelming bipartisan majorities, creating a new paradigm for how the federal government exerts influence over American schools.

And yet, who has control over educational standards has been at the center of another contentious school debate for nearly a century—that over teaching the theory of evolution. The ESSA does not directly talk about evolution, and it is quite explicit that it does not promote the teaching of religion. But it still changes the status quo. And the law could still affect the way evolution is taught across the country, because it changes how states and local districts determine what students get taught. By handing more power to the states, and to locales where antievolution sentiment is strong, the new law may spark even more political and legal battles over science education.

As it happens, the ESSA became law just a few days before the ten-year anniversary of Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, the last antievolution trial in the United States to become a mass media phenomenon. American antievolutionism is often thought of as a debate between Darwin’s account of the origin of species and a biblical interpretation of creation, but antievolution as an organized political movement has always been primarily about schools. There were religious objections to evolutionary ideas even before Darwin, but political antievolutionism really developed in the 1920s, in response to biology curricula that emphasized evolution and the expansion of compulsory education.

The Kitzmiller trial was a major landmark in the history of antievolution law. In 2004, a school board in Dover, Pennsylvania, required high school biology students to hear a short paragraph, informing them, “Darwin’s Theory is a theory,” and “is still being tested as new evidence is discovered.” Students were also to learn about intelligent design—the idea that a supernatural force deliberately designed the universe. Parents of several students sued, claiming that the school board was promoting religion by teaching intelligent design (ID). Unlike forms of creationism that hew to biblical accounts, ID advocates do not claim that the designer is the biblical God, or that creation unfolded in a manner consistent with the book of Genesis. For these reasons, intelligent design advocates claim that their theory is scientific, not religious. In his ruling in the Kitzmiller case in 2005, though, Judge John E. Jones III said that “ID is not science.” The judge further ruled that the Dover school board had violated the separation of church and state.

Since the Kitzmiller ruling, much of the political activity around evolution has shifted to state legislatures. Since 2005, according to Nicholas J. Matzke’s recent study in Science, “at least 71 bills [promoting antievolutionism] have been proposed in 16 states,” with some of these becoming law. In addition to this bevy of legislation, new textbook adoptions and new science standards have been approved by states or local districts. The local discretion of school districts and teachers means that the United States continues to be a nation in which creationism and other alternatives to teaching evolution have flourished. Events like the 2014 Ken Ham-Bill Nye creation debate become public spectacles, but the real effects in the classroom have received much less attention.

Like any major bill that passes with bipartisan support, the ESSA contains provisions that are subject to different interpretations and emphasis depending on one’s constituency. On his Senate website, bill sponsor Lamar Alexander, a Republican, emphasized that the legislation “reverses the trend toward a National School Board,” returning power to states and to local school boards instead. Senator Patty Murray, his Democratic co-sponsor, tweeted during the State of the Union address that the law “will continue to help improve achievement in STEM subjects”—meaning science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Both of these statements are true. The ESSA requires ongoing testing of students in the sciences, but it allows states (or local districts) to determine the tests and standards.

One of the most notable provisions of the act is the creation of a dedicated grant fund to create “STEM master teacher corps,” a state-led effort which the law says will elevate the status of STEM teaching “by recognizing, rewarding, attracting, and retaining outstanding science, technology, engineering, and mathematics teachers, particularly in high-need and rural schools.” In short, the bill provides money and strongly encourages states to emphasize science standards and to recruit, train, and retain talented science teachers, but it leaves the content of science standards up to the states themselves. A statement on the ESSA by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics applauds the increased support for professional development but also laments that “under the new law, state education leaders can decide how to spend professional development funds without a federal requirement that they focus on or give any priority to math or science educators.”

The reduced federal role in curricular content makes state laws even more important—because states now have the authority to approve standards that reduce the teaching of evolution, or allow for the presentations of alternatives that are asserted as scientific. Where No Child Left Behind (NCLB) gave the federal Department of Education power to set some science standards that states must adhere to, that power is stripped away by the ESSA.

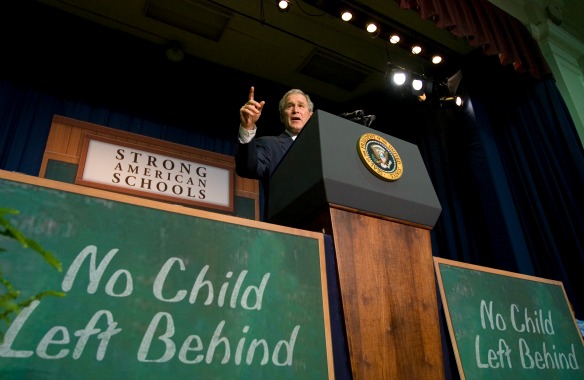

Teaching evolution alternatives like intelligent design did, however, come up during and after the passage of NCLB. The version passed by the Senate contained an amendment proposed by then-Republican Senator Rick Santorum that said “where biological evolution is taught, the curriculum should help students to understand why this subject generates so much continuing controversy.” This “Santorum Amendment” was removed before President George W. Bush signed NCLB into law (though it was included in the report of the House-Senate conference). Still, a few weeks later, two Ohio representatives wrote a letter to their state’s board of education, claiming that “the Santorum language is now part of the law” and suggesting that NCLB mandated, or at least allowed, the teaching of intelligent design.

“The Santorum Amendment certainly turned up in local policies and was cited widely by creationists, but wasn’t legally binding,” says Josh Rosenau, programs and policy director at the National Center for Science Education, an organization that promotes teaching evolution. And yet, the Discovery Institute, a think tank which supports teaching intelligent design, continued to promote the Santorum language, as recently as 2012, when Santorum was surging in the Republican presidential polls. Still posted on the institute’s website is a 2003 congressional letter from Santorum and then-Representative John Boehner that said “public school students are entitled to learn that there are differing scientific views on issues such as biological evolution.”

It would seem that with NCLB officially replaced, any question about the meaning of an old congressional conference report is now moot. But David DeWolf, legal scholar and senior fellow at the Discovery Institute, describes the Santorum language as “an aspirational statement,” intended to reflect the “sense of the Congress.” He also notes that there’s nothing in the ESSA to signal that “Congress changed its mind.” While some members of Congress would certainly dispute the idea that Santorum’s amendment reflected their intentions, there’s nothing explicitly rejecting that language in the ESSA.

When NCLB became law, the courts had not yet ruled upon the question of whether intelligent design constituted a “scientific” view. While the legal and philosophical implications continued to be debated, intelligent design has not come back into the courts. The reason it hasn’t has less to do with the legal issues involved and more to do with the financial realities of school districts in the wake of Kitzmiller. As the losing party in a civil lawsuit, the Dover Area School Board was held responsible for more than a million dollars in legal fees incurred by the plaintiffs. The risk of such a heavy cost had an immediate chilling effect on another effort to bring antievolution into the classroom. Just a few weeks after the Kitzmiller ruling, a California school district agreed to halt an elective course on the “Philosophy of Intelligent Design” after a lawsuit was filed. It’s likely that other local school districts, wary of the cost of losing lawsuits or their liability insurance, are also reluctant to bring about the next post-Kitzmiller evolution trial.

Some public schools, though, are still teaching forms of creation science. And professed belief in creationism has remained largely steady over the past 30 years, according to Gallup polls. Antievolutionism has continued to make progress on university campuses, which do not have the same stringent legal oversight as K-12 public schools. In September, the Discovery Institute published a list of highlights since the Kitzmiller decision, declaring it “an excellent decade for intelligent design.”

The next legal challenge to anti-evolution will likely come against a state’s requirements, rather than a school’s. The law’s defender will be a state attorney general with both the financial support and the political incentive to make the risk of losing worthwhile. The trials of the 1960s (Epperson v. Arkansas ruled against state antievolution laws) and 1980s (McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education and Edwards v. Aguillard both ruled against teaching “creation science”) were challenges to state laws, defended by the states themselves.

The antievolution state laws of the post-Kitzmiller era are part of new legal strategies to make them harder to challenge directly. A 2008 Louisiana law, for instance, permits teachers, schools, and districts to offer “supplemental textbooks and other instructional materials” so that students can critique “scientific theories in an objective manner.” Opponents of the bill claim that this language is code for tolerating intelligent design, or even biblically informed creationism. But the law is carefully worded: It also states that it “shall not be construed to promote any religious doctrine, promote discrimination for or against a particular set of religious beliefs, or promote discrimination for or against religion or nonreligion.” Similarly, a 2012 law passed in Tennessee permitted teachers to “review in an objective manner the scientific strengths and scientific weaknesses of existing scientific theories.” Like the Louisiana law, this law permits teachers to use their own discretion, rather than require teaching antievolutionism.

The ESSA does nothing to stand in the way of state laws that allow teachers to take a skeptical view of evolution. It makes it possible for similar laws to pass in other states without fear of losing federal funding. The language of these laws creates a scenario in which a teacher who oversteps and brings in antievolutionary materials that courts already accept as being religion may be held personally liable, rather than the school district or the state being subject to a lawsuit.

Senator Alexander’s references to a “National School Board” are an exaggeration, but there has been a movement towards the development of a more standardized curriculum in recent years. A consortium of state education boards created the Common Core standards in 2009, partly out of a desire to avoid any backlash that would result from association with Washington. Although many conservatives initially embraced Common Core, they began opposing it once the Obama administration started using its standards. This idea of national-but-not-federal standards was replicated in 2013 with the unveiling of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), whose logo includes the tagline “For States, By States.” The NGSS includes several concepts about evolution that students are expected to master, including the requirement that students understand and can “communicate scientific information that common ancestry and biological evolution are supported by multiple lines of empirical evidence.”

The ESSA does not abolish Common Core or the NGSS. It does, however, prohibit the federal incentives or rewards for adopting the Common Core standards, or “any other academic standards common to a significant number of States, or any assessment, instructional content, or curriculum aligned to such standards.” This prohibition seems to include the NGSS, though they’re not mentioned by name. Given the NGSS’s strong evolutionary content, anything that affects its adoption indirectly abets antievolutionism.

In Rosenau’s view, the pressure on states to adopt NGSS and similar standards will come from the market rather than federal incentives. “Practically speaking, well over a third of students live in states that adopted NGSS already,” he says. “Textbooks and tests and teacher training will be oriented to NGSS regardless of what the rest of the states do.” School districts less keen on teaching evolution may have little choice but to buy curriculum embracing it.

There are two competing explanations for the distinctly American fascination with creationism. One is rooted in American exceptionalism: The U.S. is a uniquely religious country, one of the only modern industrial democracies to resist widespread secularization. In this interpretation, the long history of antievolutionism—from the Scopes trial to the Ham-Nye Creation Debate—is a century of struggle between modernity and religion. But the other answer to the question of why events like Scopes or Kitzmiller happen so often in U.S. history has to do with the administration of schools. The small town of Dover can decide to present intelligent design; an individual state like Arkansas can legislate creation science. A town or state or county in a European nation doesn’t have the autonomy to make that kind of change without oversight from the national government. The ESSA exacerbates that difference, relinquishing some of the power the federal government assumed under NCLB. If this second explanation is true—if antievolutionism has less to do with a unique religious culture and more to do with federal control over schools—then the ESSA could have a big effect on teaching evolution.

Adam R. Shapiro is a historian of science, religion, and education in America. He is the author of Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools. (Twitter: @tryingbiology)