In early November, German authorities arrested eight members of the Saxony Separatists, one of a rising number of extremist groups planning for Day X, a coup that will, adherents believe, restore a Third Reich-style government. “The organisation believes beyond doubt that Germany is nearing ‘collapse,’” prosecutors said in charging the suspects. Another adherent to such ideas happens to now be working at the White House: the German far-right has found a booster in presidential adviser Elon Musk, who recently told supporters of the no-longer-fringe Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party to reject “past guilt” for the Holocaust, and shun multiculturalism. It’s a recipe for a disaster that Germany knows all too well. Yet some are seemingly keen to try it.

The historian Terrence C. Petty discusses this recent recrudescence of German right-wing extremism in Nazis at the Watercooler (University of Nebraska Press, 2024), his fascinating new book about the disturbing extent to which West Germany’s postwar bureaucracy, and its security services in particular, welcomed ex-Nazis into its midst. In fact, officials “doing the hiring actually preferred civil servants who had worked for the Third Reich because of their professional experience,” Petty writes. On the other hand, “there was virtually no effort to recruit people for the civil service who had been persecuted by the Nazis. They were simply not wanted.”

A former reporter for the Associated Press who worked in Germany, Petty has written two books about the internal resistance to Hitler. This book, on the other hand, is about Hitler’s willing executioners (as for the title, it’s a joke—Nazis were not known for their watercooler small-talk): men like Werner Catel, who had been a “consultant to the Nazi regime” on the T-4 program, the mass extermination of disabled people that served as the precursor to the Holocaust. Catel was specifically tasked with killing those he deemed “incurable idiots.” And that’s how he talked after the war. An unrepentant butcher, Catel was, by 1948, a public health official working on tuberculosis inoculation.

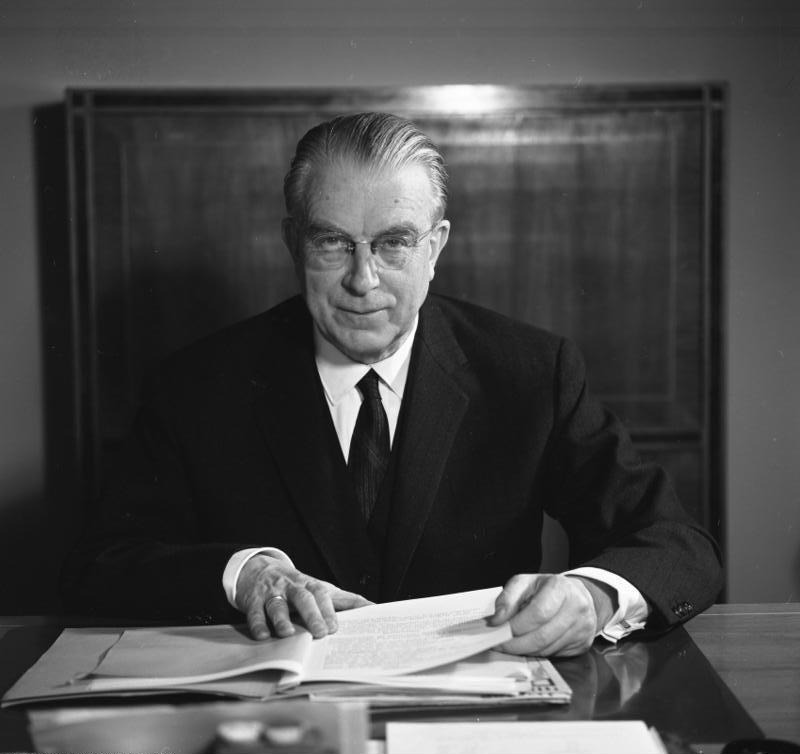

“At the Interior Ministry in the late 1950s, two-thirds of employees in the higher levels of civil service were former members of the Nazi Party,” Petty writes. “At the Justice Ministry, about half the senior employees had been card-carrying Nazis. The figure was an astonishing 80 percent at the Agriculture Ministry.” He blames this state of affairs on chancellor Konrad Adenauer. Himself no Nazi during the war, Adenauer saw hiring ex-Nazis as a matter of expediency: “You can’t throw out dirty water if you don’t have fresh water.”

The water remains murky. Petty makes clear that no right-wing resurgence like the one Germany is experiencing today—violent would-be conspiracists aside, the AfD has done plenty to mainstream Nazism again—would have been possible had so many former Nazis not been invited into the highest ranks of the West German government. That invitation came, in part, at the behest (or, at least, with the encouragement) of the United States, which quickly pivoted to a new foe once the war was over: “the vanquished tribe whose emblem had been the swastika would join forces with the American conquerors to stand against the rival conquerors, represented by hammer and sickle,” Petty writes.

“At the Interior Ministry in the late 1950s, two-thirds of employees in the higher levels of civil service were former members of the Nazi Party,” Petty writes. “At the Justice Ministry, about half the senior employees had been card-carrying Nazis. The figure was an astonishing 80 percent at the Agriculture Ministry.”

Petty opens Nazis at the Watercooler with the story of attorney Hans Globke. Though never a member of the Nazi Party, Globke had helped craft the Nuremberg Laws, which, once implemented, made Jews the lowest class of German citizenry. After the war, he spent some time in an American internment camp, where he “contacted people about writing testimonials that would help exonerate him during the denazification process.” It worked, and how; Globke rose to become Adenauer’s chief of staff.

Incredibly, as a West German official, Globke would prove instrumental in approving the $5.5 billion loan that helped Israel stand up a nuclear program at Dimona. Make moral sense of that one, if you can. For all its strengths, Petty’s book does not grapple with the complex postwar relationship between West Germany and Israel, in part, I suspect, because doing so would uncomfortably suggest that even some truly execrable figures were capable of at least pretending to be normal human beings, once loosed from Hitler’s fanatical grip.

But could so many Nazis change so much? One could argue that West German policy toward Israel only disguises the degree to which the vestiges of the Third Reich remained ingrained in the body politic. At one point, “two dozen” of the “top men” in the Bundeskriminalamt federal police agency “had served with Nazi units that had committed war crimes,” Petty writes. That statistic comes from the investigation of Dieter Schenk, one of several prosecutors, investigators, and journalists who refused to let sleeping dogs lie (the prosecutor Fritz Bauer was another key figure in this effort). On the whole, though, efforts at expurgating Nazi presence in West German bureaucratic ranks proved futile. There were simply too many of them. Truth will out, as they say, but expediency will cover it right up again.

Even many decades later, Petty suggests, with most of those ex-Nazis long gone, their influence remains at work, less as a set of policies than a tolerance for fascism held in collective abeyance. “The idea that civil servants of the Third Reich were nonpolitical is one tributary of a broad river of denial and defensive delusion that coursed through West German society,” he writes.

And while it is easy enough to tut-tut the incorrigible Germans, we might take a look at our own society, which only recently—and reluctantly—began to treat Confederate statues and memorials as the symbols of racist insurrection they have always been. And for every Nikki Haley, who ordered the removal of the Confederate flag from the state capitol grounds when she was governor of South Carolina, there is a Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who has flatly expressed his disapproval of any such moves.

Meanwhile, the next four years will see Washington rife with officials who supported political violence that took place as recently as Jan. 6, 2021. Many of the rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol that day had ties to extremists groups; one, infamously, wore a “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt. These were the figures President Trump pardoned on his first day in office, with the tacit if not explicit support of his party.

Imperfect as the German reckoning has been, their Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung—the process of working off the past—has fostered a prevailing sense of what dangers lie behind the lure of radical populism. We, on the other hand, might be rushing towards those dangers with full abandon.