The most successful social movements sustain themselves in part because they’re fun. The activist push in the LGBTQIA+ community that began with the Stonewall riots in 1969 and proceeded through the AIDS epidemic and the legalization of same-sex marriage went hand in hand with an outpouring of culture. William S. Burroughs novels and Stone Butch Blues were on bookshelves. Falsettos and the stone-cold masterpiece Angels in America were on theater stages. In the 1980s, clubs churned out one genre of beat-heavy music after another that keep dance floors packed to this day and spilled over time and again into popular music, from New Wave to synth pop. The 1990s saw Lilith Fair, the Indigo Girls, Melissa Etheridge, Tracy Chapman, and Ani DiFranco. It was all accompanied by big fashion statements, whether it was the glitz in Studio 54 or the earthiness in a Northampton church, commandeered for a night. The art mattered because it made the goal of the fight tangible. It imagined, and even sometimes created, places where people could be themselves without reserve. Decades before the change came, the art gave everyone involved a taste of what it felt like to live as if that change had already come.

Likewise, the global push for Black liberation, from the militant side of the civil rights movement in the United States to the fights for independence and equality across the Caribbean and Africa, found its voice not only in the amplified speeches of its political leaders, but also in the irresistible beats of its cross-cultural soundtrack, from James Brown, Parliament-Funkadelic, and the rise of hip hop culture in the United States, to Fela Kuti in Nigeria, to Bob Marley and the Wailers out of Jamaica, to Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited in Zimbabwe, to a near-army of musicians in South Africa pumping out indomitable rhythms to the push to end apartheid. Beyond the speeches, the rallies, the political organizing, the art makes its own case. With a soundtrack like that, who doesn’t want to come to the party?

Think of that iconic 1968 photograph of Huey Newton, the Black Panthers’ minister of defense, sitting on a rattan throne in his black leather jacket, flanked by Zulu shields, a zebra rug at his feet, a shotgun in one hand and a spear in the other. His beret is cocked at a serious slant. There was text running along the bottom of some reproductions of that image: “The racist dog policemen must withdraw immediately from our communities, cease their wanton murder and brutality and torture of black people, or face the wrath of the armed people.” I’m told that photo scared the crap out of a lot of white people at the time, and within a few years, the FBI and other law enforcement agencies would do their best to destroy the party Newton represented. The Black Panthers officially disbanded in 1982. But their legacy has persisted, in politics and art, and that photograph of Newton is part of the reason why. More than fifty years later, the image’s power isn’t derived just from its place in the history of politics and race relations in the United States. We also remember it because Newton looks amazing, and you can tell he knows it. Our gut-level reaction to the image—as a piece of art—matters. It may seem superficial. It isn’t. Today, somewhere, someone who has no idea who the Black Panthers were will see that image and think: who is that? I want to know.

But why does the image work on us like that? How does any image—or piece of music, or play, or, for that matter, a delicious meal, or a fetching hat, a chalk drawing on the sidewalk—do what it does? This nebulous yet somehow oddly precise question is the subject of What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory (Faber & Faber, 2025), by Brian Eno and Bette A., a slim, lively volume that takes no more than a couple hours to read, yet draws from decades of experience making and considering art and comes up with a complex and genuinely subversive set of ideas that feels, in our current political moment, like it arrived at just the right time.

At first glance, the book can seem almost facile, starting with its overall look. The cover is bright pink, the title all in lowercase, in a friendly font. There’s a lot of fun, playful layout on the pages. Bette A.’s illustrations are simple pen and ink drawings, sometimes but not always accented with a few colors. The sense of easiness extends to Eno’s prose. He doesn’t use big words; he has said that he pitched the language to be able to connect to a teenager, but the prose is straightforward enough that a precocious grade-school student could read it. All this leads The Guardian to call the book “disarmingly simple”—“disarming” is a well-chosen word here—with the writer, David Shariatmadari, showing some evidence of having been a little disarmed himself. “The ideas are more complex than the presentation suggests, but not vastly,” he writes. “Neither is it exactly breaking new ground. The point isn’t to be original, though, but to distil a lifetime’s worth of practical wisdom and reflection.”

In Brian Eno’s case, however, that lifetime being reflected carries some weight. Whether something is a platitude or a hard-earned kernel of wisdom depends on who’s speaking. If I tell you that you really need to practice your free throw to make it to the NBA, it’s worth nothing. If LeBron James does, it’s everything.

A musician and visual artist, Eno is a LeBron James of art. He’s a founding member of Roxy Music and is credited with having created an entire musical genre—ambient—beginning more or less with the 1978 album Music for Airports, designed to be played on continuous loop at air terminals to help passengers cope (or perhaps come to terms) with the latent fear of dying in a plane crash. He is also a consummate collaborator. As a music producer, he has the uncanny ability to help musicians at all levels up their game, making what many people still think are their best albums, whether it’s David Bowie (Low, Heroes, and Lodger), Talking Heads (Remain in Light), U2 (Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby) James (Laid), or Coldplay (Viva la Vida or Death and All His Friends).

That last one is especially important, as by the time Chris Martin, Coldplay’s lead singer, approached Eno, Eno already had his reputation, and in an initial conversation, showed the work, the discipline, the shrewdness, right behind the serene façade. From a Rolling Stone interview by Brian Hiatt with Martin, in 2008:

What was the mood of the band going into your new record?

On our last album we took a beating from some people, and by the end we felt like no producer would want to work with us, basically. We were bigger than we were good—we were very hungry to improve on a basic level. So I asked Brian Eno, “Do you know any producers who could help us get better as a band?” And he said, “Well, I don’t mean to blow my own trumpet, but I might be the man.”

What was his assessment?

He goes, “Your songs are too long. And you’re too repetitive, and you use the same tricks too much, and big things aren’t necessarily good things and you use the same sounds too much, and your lyrics aren’t good enough.” He broke it down.

How did you respond?

You deal with it. You can either sit ’round, look at your platinum discs and say, “Fuck you, you’re all wrong,” or you can go, “OK, he’s probably got a point.” Brian and Markus [Dravs, the co-producer] broke us down in a sort of military boot-camp way. Within twenty minutes we’d forgotten about any previous record sales.

Married to Eno’s keen, ruthless sense of how to avoid making bad art is an impish, playful sense of how to make something good—how to create art that satisfies and subverts, that reaffirms and denies, that puts together elements everyone likes (say, a killer beat, a strong melody) with a sound no one’s ever heard before. His attitude toward artmaking finds some of its expression in his Oblique Strategies, a set of cards he created to help him keep a music recording project moving forward after hitting a creative impasse. Some of the cards are quite practical (“is the intonation correct?”; “convert a melodic element into a rhythmic element”; “are there sections? Consider transitions”). Some are funny (“tape your mouth”; “look closely at the most embarrassing details and amplify them”; “change nothing and continue with immaculate consistency”). Others are like koans or fortune cookies (“discard an axiom”; “in total darkness, or in a very large room, very quietly”; “once the search is in progress, something will be found”). All have the same goal: to change the frame, to move you, to get you to think about a problem from a different angle, and from there, see a new way forward. What Oblique Strategies does for specific art projects, What Art Does hints at doing for the way we understand ourselves and—here comes a big statement, but bear with me—the power we have to imagine and create the future we want, whether those who claim power and authority over us like it or not.

“Making art seems to be a universal human activity,” Eno writes, adding that people say “art helps me see the world, art helps me understand the world, art helps me imagine new worlds, art helps me to escape, connect, relax, energize, forget, remember, heal, disrupt, recognize, resist, forgive, accept, change … but what does art do? If we can’t answer that question then we shouldn’t be surprised when governments marginalize the arts and humanities in education, or when the ‘brighter’ students are directed away from the arts and into science and tech, or when support for theaters, libraries, and concert halls is the first thing to be withdrawn in a financial squeeze.” This matter-of-fact statement hints at the deeper direction the book is heading in.

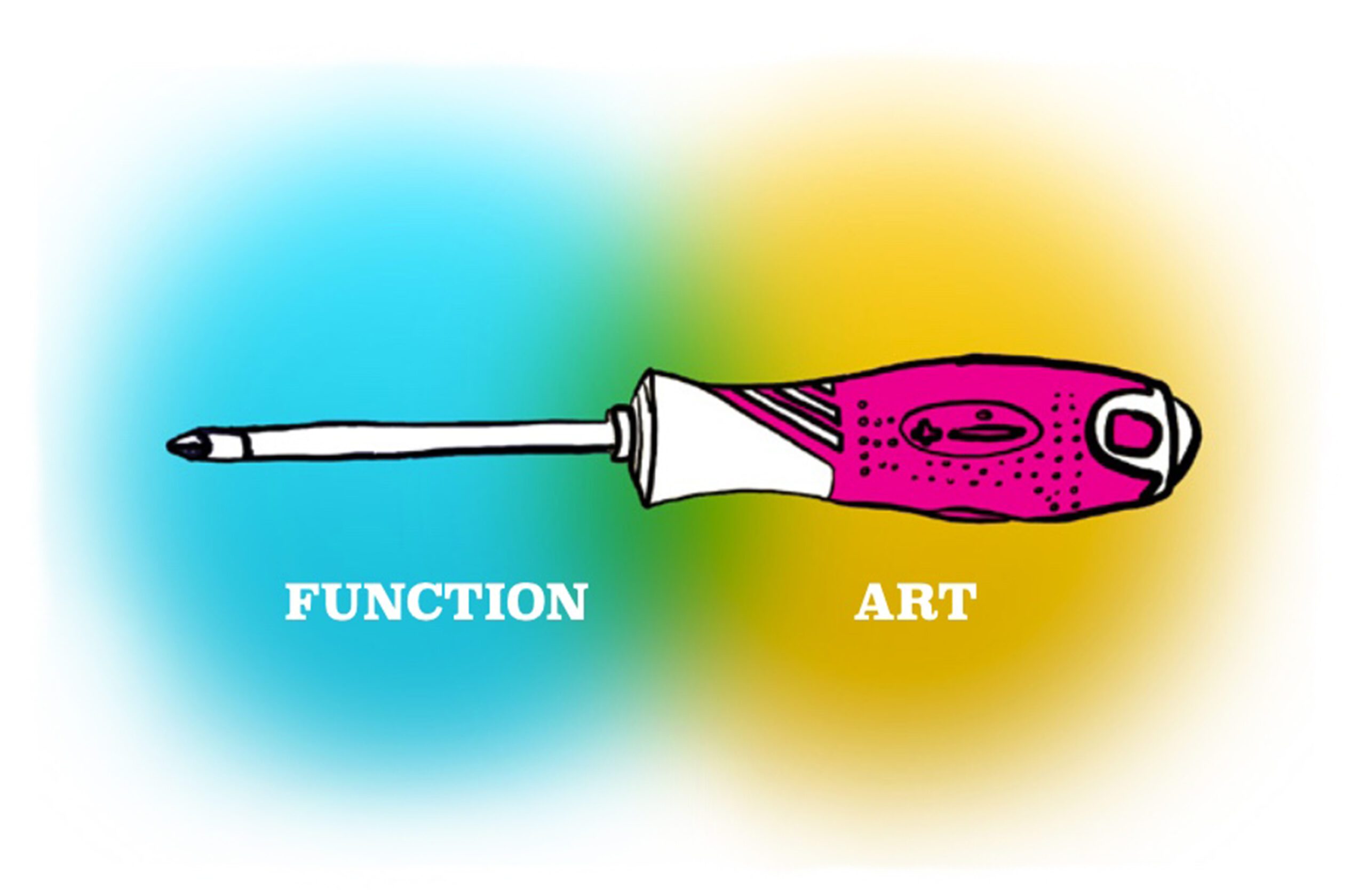

But first, discussing the question of what art does requires a definition of art, which, under normal circumstances, is a good reason to put a book down; as musician Elvis Costello said once (though he denies coining the phrase), “writing about music is like dancing about architecture—it’s a really stupid thing to want to do.” Eno, however, comes up with something surprisingly workable. In a 2015 lecture, he defined art as “everything you don’t have to do.” In What Art Does, he elaborates: we have to gather food, but we don’t have to add sprinkles. We have to construct shelter, but we don’t have to hang wallpaper. We have to communicate, but we don’t have to do improv. We have to maintain our body, but we don’t have to do bodybuilding. “We all make art all the time, but we don’t usually call it that.”

“Here’s a simple idea: Art is a way of making feelings happen.”

And there is room for art wherever there is ambiguity, wherever there are options. “Many activities are part-art, part-function,” Eno writes. We may have to run for a bus, but we might choose to skip. And it’s the bus driver’s job to get her passengers to her destination, but “a joke the bus driver makes as she announces the stops, a bird tattoo poking out from under her uniform sleeve, a little movement of her shoulder when she thinks of her favorite song—these are little expressions of art.” The generosity of the definition matters; Eno intends the book to apply not just to professional artists, “people who have decided to make a job of it,” but to everyone.

“Why do we spend our time on these non-functional activities we call art?” Eno writes. “Here’s a simple idea: Art is a way of making feelings happen.” Feelings, he continues, are so often dismissed, often as getting in the way of rational thought. And yet they’re instrumental in guiding our decisions, and often are fundamental in how we make the biggest decisions of our lives. We marry because we love. We live in one neighborhood over another because we like it more. We may take one job over another because we hit it off with the person interviewing us. Art lets us practice feeling these feelings, and helps us learn how to use them, without immediate consequences. “Art is effective because it is safe,” Eno writes—perhaps the slyest wink in the whole book. It bolsters his general argument about why we engage in art day after day. But on the same page, he points out that “there are many examples of art changing the course of history, advancing revolutions, bringing stone-cold people to tears and horrifying conservative parents. Art can have a tremendous effect on the world—that is why dictators have been so eager to lock artists away or employ them as propagandists.”

Does that sound safe? Eno moves on in his nonchalant way. Art is a “simulator” of “fiction feelings,” he writes. When engaging a piece of art, “you are allowed to take the consequences as seriously and as non-seriously as you want. The level of seriousness is entirely up to you.” Eno puts his thumb on the scale; there is such a thing as too serious, a point when “a large part of someone’s life takes place in a fictional game and the developments in that game truly affect them…. Conspiracy theories are perhaps games gone wrong.” Problems happen when “they are no longer playful.” Play, lightness, saves us from falling into that trap.

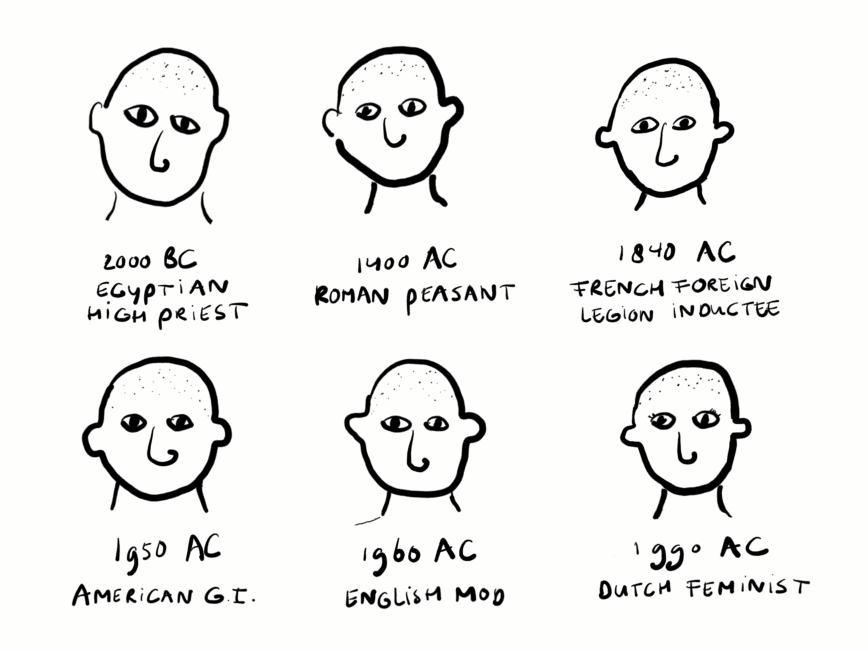

The emphasis on play makes a lot of sense in the context of the book, which has an entire short chapter revolving around haircuts to make points about self-expression and how the signals and meanings of that expression can change across time and from place to place. “Play is how children learn,” Eno writes, and “art is how adults play.” When we’re children and adults, play helps us develop the muscle of our imagination, and “imagining is the great human skill.” The art made through that play can be “a channel into another universe, or like relics from the future. They’re pulled into our reality as representatives from another reality.” For Eno, that’s true whether the piece of art in question is a novel, a song, or a small earring. “It’s like finding a fragment of a different world.” We get to have feelings about it, and decide what to do with them. “Our feelings guide us as we move into new futures.”

“Play is how children learn,” Eno writes, and “art is how adults play.”

The language is deceptively simple and comforting, the illustrations winsome and charming. Which is why it’s easy to miss the weight of Eno’s next move. “What is it I really like?” Eno asks at the beginning of the seventh chapter. “You recall those moments in life when you’ve seen or heard something that has stopped you in your tracks. The feeling of being overpowered, entranced by something, of wanting to see it more and more or to hear it again and again: that’s when you know you really like something.” And “to discover what you really like is to have a guiding star and to be able to navigate through the blizzard of all the voices telling you what you ought to like—the advertisers, politicians, influencers, ideologues, algorithms. It is your claim to independence of mind (even if a billion other people like it too!).”

Eno’s lumping together of political and commercial actors alongside an algorithm matters. Nestled within that is the kernel of something, in a way, more powerful than resistance. Resisting something implies that, on some level, you take whatever is being imposed upon you seriously. Eno suggests instead a casual, easy dismissal. Why push against a rule when you can just blithely ignore it? As he says, the level of seriousness is entirely up to you. Eno continues, the tone as light as ever, but now the target of that tone is coming into greater focus: “Certain forms of art get criticized for being escapist. There’s an assumption that good art must always be difficult in some way. But what’s wrong with escaping? What’s wrong with wanting to experience another reality that is better than this one? What does that tell you about this one? If you find out what ‘better’ means for you, you have a richer understanding of the world you’re in and what is missing.”

The seventh chapter is titled “How Does Art Change Me?,” and if it stopped there, we might be left with a well-articulated but familiar view of art and artists as part of but also somewhat apart from the society around them. Eno’s starting point, however—that everyone is an artist, that you are making art as soon as you put jam on a piece of bread, or wear a t-shirt with a design on it, or paint your house yellow—makes it impossible for his ideas to land in that conventional spot. So the book moves from the question “how does art change me?” to “how does art change us?” With that shift, the nonchalant tone suddenly acquires an edge, akin to discovering, just a second too late, that the cute green bird that landed on your shoulder and sang a gorgeous little song also has a beak lined with razors.

“Art is where we share our dreams (and nightmares),” Eno writes. “Art is one of the things that binds people together. Or on the other hand, allows them to define themselves as separate.” If art is the result of exercising our imaginations, “civilization is shared imagination.” Sharing that imagination, Eno states with the same breezy tone he began with, can lead to huge changes in societal attitudes: “wanting to imagine a world that doesn’t have simple good/bad distinctions,” “being critical of bureaucratic procedures,” “aligning with a non-binary approach to gender,” or “believing the human spirit is stronger than any oppressive government.” Eno continues: “One of the primary ways we become comfortable with that sort of societal shift is by first of all modeling it, or seeing it being modeled, in art.” He adds—at this point in a deliciously disingenuous parenthesis—“(remember: art is safe).”

By sharing art and our feelings about it, Eno says, we can make community, a move that feels more important than ever, and at odds with what we are being told to do. “Especially in the consumer era, we’ve been encouraged to think of ourselves as separate and independent individuals, whereas our strength as a species comes from our ability to continually adjust and cooperate. Art is one of the most powerful ways of doing that.” For Eno, however, working as a community isn’t about creating strictly like-minded people; it’s about a group of people, together and for themselves, finding a balance between controlling some things and surrendering to others—things that can give us pleasure, that can make the place we live in better, new ways of thinking and doing. “If we don’t learn to make a balance between control and surrender, if we only know how to control, we end up in a world shrunken to the bits that we can still control,” Eno writes. “The raw wild world develops and leaves us behind, playing Solitaire on our phones.”

The act of surrender extends to making art and to ourselves, and here’s where Eno ties it together. “Writer Stewart Brand says of buildings: ‘You don’t finish a building: you start it . . . ’ . . . and that is the way we could think about artworks and, probably, our lives. As artists, we don’t finish it: we start it. It goes on to have a life without us, a life we didn’t predict.” In that way, art—and the broader culture it’s a part of—is alive. But “most importantly,” Eno continues,

we might start to think the same way about ourselves: that we are unfinished (and unfinishable) beings whose task is constantly to reexamine and remix our ideas and our identities.

An attitude like this equips us better to deal with planetary emergencies like climate change and the crises of governance. For although we will certainly need new regulations, laws and technical advances, beyond all of those we will need imagination, new imaginings.

“We need new means, not old ends,” Eno writes. “In whatever we are doing, we have to make it as though we are in that new world” already. “By making objects, systems, experiences and collaborations that belong to that world, it comes into being. Live the world you want. What kind of world would that be for you?”

If the idea of a single person guided by their own likes, ignoring the constraints put upon them, wasn’t sexy and fun enough, that idea writ large, across an entire group, an entire society, feels revolutionary. But imagine this revolution less as a scene of looted buildings and buses on fire, and more as a sense of people relaxing into a newfound sense of freedom and possibility, of looking at the rules that govern them—and the powers that be that say those rules must be followed—and instead of acquiescing or resisting, keeping them only if they feel right, bending them to suit their purposes, or just waving them away like a bad smell, leaving them in the past if they’re getting in the way of the future.

What does that future look like today? Artists have always lived hand to mouth, always made something out of nothing, with scarce resources at hand, but the current political climate is about as hostile toward the arts as it has been in the twenty-first century. Across the world, countries have experienced a rightward swing, toward more authoritarian modes of government, promising stability for some in exchange for oppression toward others. The U.S. government has seriously curtailed how much it funds the arts, and severely limited what subjects the art it does fund can address, and state and local options are few and far between. Freedom of expression, especially for the overlapping mosaic of marginalized communities that often have been the wellsprings for innovation in the arts in the United States, is under pressure. Add to this that many longstanding arts venues and institutions imploded during the COVID-19 pandemic, or have yet to fully recover, and things can look a little bleak, not just for working artists who are trying to make a living, but for everyone practicing an art at all—which, Eno would say, is really all of us.

In the past several years, in response, the political left has become very adept at a particular form of resistance. It knows how to organize, how to get followers to show up, for protests, rallies, marches, and encampments. Its messages are clear, its list of issues well-defined. But despite the strong rhetoric from political leaders, a new, broad political movement has yet to emerge that balances the movement on the right. Part of the reason, say some critics, is because it lacks an overall vision. It has a series of talking points, but no grand ideas, no clear unifying direction, no tangible sense of what society might look, sound, or feel like to live in if the changes the left is talking about are implemented. People get it. But they don’t see it. They can’t imagine it. Why not?

From an arts perspective, it’s hard not to notice that the left also lacks a corresponding new aesthetic movement, one that is making new art. Many individual artists are confronting political questions, and some of them—like musicians Kendrick Lamar or Chappell Roan—are making good art and commanding a lot of attention. But where is the groundswell beyond the big names? The anti-war protest movements in the 1960s spawned an entire hippie counterculture of music, writing, and fashion. The Black liberation movement spawned not just new musical acts, but entire musical genres (funk, reggae, Afrobeat) with their own looks, literature, and lifestyles to go with them, often grounded in deep senses of spirituality. The effects went far beyond the handful of innovators who created it: hundreds if not thousands of artists continued the work where the pioneers left off. Political disaffection in the 1970s went hand in hand, for different reasons, with punk and disco—both of which also offered entire lifestyles of music, dance, and fashion—and even more important, was a critical ingredient in the formation of hip hop, a swirling, incredibly fertile mixture of music, poetry, dance, and visual art that roared out of house parties in the South Bronx and today is the dominant form of popular culture in the United States. These movements go far deeper than revered trailblazers and marquee names; for thousands upon thousands of people, they were and are codes of conduct, ways of life, rich communities. They were and are, in short, fun. That sounds dismissive, but it’s not. Fun, lightness, joy, are vital. As Dan Savage said, “the dance kept us in the fight because it was the dance we were fighting for.”

It’s hard not to notice that the left lacks a corresponding new aesthetic movement, one that is making new art.

Today’s political resistance is many things, but one thing it is not is fun. Put into Eno’s terms, there’s little sense of play. It’s possible that this is actually a major problem. If Eno is right—if play is how good art gets made in the first place and how people engage with it, and art is how we create and try out our visions for the future—then the link between our current political resistance to oppression not being fun and not having a coherent vision that others want to join is causal. We don’t have a vision because we’re not having fun. And even if Eno’s wrong, where’s the party—in both senses of the word—that people who aren’t already there want to join? Where’s the new beat that draws them in and keeps them up until dawn

The question isn’t as despondent as it sounds. The Guardian describes What Art Does as a “joyous manifesto: just the thing to inspire a teenager (or adult) into a new creative phase.” It’s an apt description, especially as the book is made by two working artists who are, in turn, part of a large and thriving arts community. What Art Does comes out of the full certainty that people will create art no matter what the conditions, a stance borne out by countless examples throughout history and across the world. Authors wrote novels in Soviet Russia that got passed around from hand to hand. Enslaved people in the United States held dances every week. Writers write, musicians play, painters paint, sculptors sculpt, and most of them make what they want—often to their own material detriment—regardless of what political or commercial forces dictate to them. It’s not so much resistance as persistence, and it’s in search of something much bigger than winning the next election, or getting through the next few years. It’s very likely that, right now, thousands of artists—by which Eno would mean all of us—are crafting a collective vision for a better future, one that has a place for everyone. What brings us together to manifest it in the real world might not be a viral post for the next protest, but a new sound, a new rhythm, that artists are already working on, right now. Something that’s really about fun. Something no one has ever quite heard before, but no one can resist. All we have to do is keep our ears open to hear it.