Picture the year 2050: a world of ubiquitous renewable energy, cheap desalinated water, vertical skyscraper farms, lab-grown meat, “star pills” manufactured in orbit that reverse aging, addiction, and obesity. “Your friends are flying from New York to London” in a supersonic jet powered by “a mix of traditional and green synthetic fuels that release far less carbon into the air.”

This likable vision of the future comes from Abundance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new work of political imagination. During the Biden years, Klein and Thompson came to be leading public voices for liberalism. From his perch at The New York Times, Klein writes an influential column and hosts an even more influential podcast. His first book explored the reasons the U.S. seems to have become more politically polarized since the 1990s. Thompson writes for The Atlantic, and he has explored the intersection of technology, economics, and culture across two books and his own podcast with Ringer.

They surely hoped their new co-authored book, Abundance (Avid Reader, 2025), would inform the priorities of the Democrats in 2024. But the book came too late for that. Instead, it has been received as a diagnosis for what has gone wrong, and what the Democratic Party might do to course-correct. Together, Klein and Thompson lay out a bold agenda for the future of liberalism. Their book has been a huge bestseller and has made the rounds of all the social media platforms, arousing praise and pique in equal measure.

As a political program, Abundance has its strengths and weaknesses—but that’s not the interesting thing about it. What’s intriguing about it—and weird, and too little discussed—is how science fiction imagery wends its way through the book. To inspire action, Abundance tells a science-fictional story of a better future. This storytelling is a strength but also a limitation. The limitless future the book evokes is appealing, but how we get there is undercooked and ambiguous. Great political science fiction spins a theory of change. We come away convinced that we might indeed someday inhabit a powerfully reimagined world.

Abundance laments that the United States government seems to have lost its ability to build. There is a chronic undersupply of housing, the authors argue. Projects such as high-speed rail have gone nowhere fast, despite ample public funding. Solar and wind projects get bogged down in red tape. They identify as liberals, but Klein and Thompson tell a story in which liberals feature as well-meaning villains. We have sabotaged ourselves by setting up onerous regulations. We are a nation of lawyers and litigious individuals. By overly empowering ourselves as individuals, we have failed to address our greatest public needs—housing, energy, and transportation.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that our failure to build is largely chosen. We can do so much better, if we simply decide to change our politics. And, Klein and Thompson argue, we must, or face dire consequences.

Contrasting this argument with other emergent and dominant sci-fi inspired political visions on the left and the right can show us why Klein and Thompson’s call to action feels wanting. Abundance envisions a compelling destination but gives an only thinly imagined vision of political economy. “[T]o have the future we want,” they write, “we need to build and invent more of what we need. That’s it. That’s the thesis.”

I appreciate that Abundance does not want to read like a white paper, but Klein and Thompson are wonks at heart. It seems fair then to ask: who will build this better future? By what means?

What’s intriguing about Abundance—and weird, and too little discussed—is how science fiction imagery wends its way through the book.

What, for instance, does one do for a living in the year 2050, if, “[t]hanks to higher productivity from AI, most people can complete what used to be a full week of work in a few days”? This is a post-scarcity world of free lunches. It’s an AI-powered future in which there seems to be no politics. After all, if our fundamental choice is between abundance or scarcity, more or less of all (and only) the good things we want, who could imagine choosing the other side?

Klein and Thompson don’t mean this portrait of 2050 to be a blueprint, just an imaginative provocation. It’s a brief opening gambit, a way to inspire us to think beyond what they elsewhere call the “chosen scarcities” of the present moment of stagnation. But even as inspiration, it’s too frictionless and unearned, a vision that highlights key gaps in their thesis.

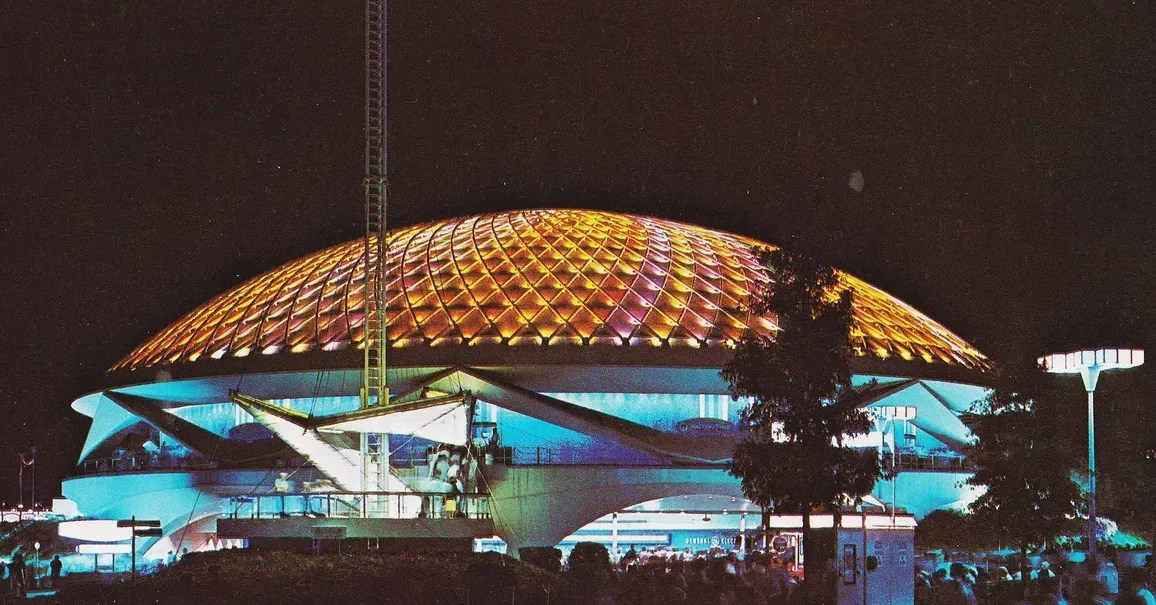

Another irruption of science fiction comes in the conclusion, when the authors recount the World’s Fair of 1964, in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, in Queens. They invoke the era’s vision of an abundant future: Bell Labs’s Picturephone, Westinghouse’s electronic toothbrush and credit card, and General Motors’s “Futurama II” exhibit, which imagined a city on the moon. We have built many of these technologies, but our present cannot help but seem a little grubby when compared to this ambitious midcentury optimism.

What went wrong? Where are our jetpacks?

Futurama II might be the name, too, of the science-fictional ethos of Abundance. It claims to be future-oriented, but it looks forward by looking back. The book reads like the sequel to a popular science-fiction franchise that hopes to—but can’t quite—replicate the original, mostly reminding us of what we’ve lost. As the law professor Noah Kazis has noted, Abundance is a “utopian project,” one built on a qualified nostalgia for a midcentury moment of economic growth and political consensus.

Ours, meanwhile, is a moment of secular decline and political gridlock.

We have plenty of reasons not to be nostalgic for that lost moment, as both Klein and Thompson recognize. But how did we lose our moxie? There is disagreement about the causes. But the sluggish growth and deindustrialization that started in the 1970s are surely part of the story. Klein and Thompson don’t talk about these factors, preferring instead to focus on more specific problems, framing scarcity not as a consequence of political-economic trends but of bad, contingent policy choices.

Deindustrialization is usually described as a story of automation and offshoring. Capitalist firms replace labor with cheaper labor or with robots, chasing profits, resulting in huge productivity gains, even as wage growth has stagnated and inequality has escalated. Superstar firms capture a growing share of GDP. These firms tend to contribute less to labor income, facilitating the decline of labor’s share of the economic pie.

What went wrong? Where are our jetpacks?

Automation threw industrial workers into the service sector. After a peak in the 1950s, American union density has fallen to pre–New Deal levels, except in the public sector. Many factors have contributed to the decline, from NLRB regulations to right-to-work (RTW) laws. Corporations spend $300–$400 million annually to counter organizing drives. Sluggish macro-economic conditions can dampen the success of campaigns, weakening worker leverage.

These dire distributional outcomes have arguably led to a decline in social trust and solidarity, fueling the rise of a new populism, on the left and the right, that speaks to deep political dissatisfaction. Abundance expresses consistent support for unions, especially in the public sector, but offers no clear roadmap for reversing their six-decade decline; Klein and Thompson don’t pretend otherwise. We can’t go back, it seems.

To be sure, Klein and Thompson aren’t trying to write a book about reversing deindustrialization. After all, other advanced economies have deindustrialized, and they have high-speed rail. Why not us? Klein and Thompson ultimately define abundance not in terms of economic growth but as the capacity to produce the things we need, like infrastructure, housing, scientific research, and a system for turning good ideas into affordable products. What matters is not dollars spent but results.

But by not discussing deindustrialization, they ignore a significant cause of the American institutional sclerosis they everywhere observe. Supply constraints aren’t just the result of bad permitting rules, sluggish bureaucracies, and vetocracy; they also arrive downwind of big structural changes to the economy. And Abundance isn’t calling for a few small-bore tweaks to our current politics. It has a vision of vastly expanding the supply of many things we need, providing radically more of just about everything—and in a big hurry.

If that’s the goal, the question becomes what kind of individual or collective agent can enact changes comparable to—or even greater than—the mobilization for World War II. After all, anything is possible if only enough of us agree. We did it before. How do we do it again?

In the 1930s, a militant and growing labor movement created a political environment ripe for radical change, paving the way for the New Deal. FDR was not a radical, but he won in a landslide, entering the White House with large Democratic majorities backing him. The bombing of Pearl Harbor turned a nation largely opposed to entering World War II into a determined participant, facilitating a mass mobilization that not only defeated fascism but decisively ended the Great Depression.

What coalition can win the future today? What force can turn the economic tide?

A more nuanced science fictional imagination might have helped Abundance come up with answers.

For example, advocates for the Green New Deal tied their ambitious bid to combat climate change to an industrial policy that sought to counteract, if not reverse, the lingering damage of deindustrialization. This strategy might be condemned as a textbook example of what Klein has called “everything-bagel liberalism”—the counterproductive tendency among Democratic policy makers to try to solve multiple objectives with a single policy—but the Green New Deal was informed by a belief that radical environmental policy would need to be sold to skeptical coalition partners.

The Green New Deal was only one example of an ambitious flourishing of speculative political thought on the left in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. This efflorescence often found in science fiction a language for talking about their hopes for a better future, turning to a rhetoric of abundance, automation, and plenty. A wave of leftist manifestos—penned by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams; Paul Mason; and Peter Frase—sought to imagine postcapitalist societies. These left-of-center writers began to hope that the end-of-history consensus that there’s no viable alternative to global capitalism was breaking down.

The leftist science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson wrote a bracing eco-socialist novel, The Ministry for the Future (Orbit, 2020), which imagines the formation of a UN-backed agency with the mandate to fight the climate crisis and speak for future generations. But top-down solutions are not enough in the novel. The Ministry is hobbled by bureaucracy and a limited mandate. Only the addition of mass mobilization and eco-terrorism, alongside technological breakthroughs such as carbon capture and blockchain-based “carbon coins,” can salvage the planet.

In 2019, Aaron Bastani published Fully Automated Luxury Communism (Verso), which invoked a similar rhetoric, offering a post-work, post-scarcity vision of the future, in which humans overcome the need to work, hold productive resources in common, and share the fruits of a post-scarcity economy, driven by automation. Bastani’s phrase, which he first coined in 2014, inspired the meme, “Fully Automated Luxury Gay Space Communism,” which added that the post-scarcity world of the future would also abolish repressive gender norms. Klein and Thompson cite Bastani, but they keep him and this anti-capitalist alternative more generally at arm’s length.

Klein and Thompson also avoid talking about the right’s science-fictional visions of abundance. Perhaps because what they’re calling for can seem so superficially similar, they hardly engage with this vision at all.

They don’t once mention the Trump-supporting venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, even though Klein engaged at length with Andreessen’s 2020 manifesto “It’s Time to Build.” They’re clearly thinking of him when they call for a “liberalism that builds,” and Klein wrote a lengthy response to Andreessen in Vox and has elsewhere insightfully discussed what he calls the “reactionary futurism” of Andreessen.

They mention Elon Musk only a handful of times, observing correctly that the world’s richest man benefited from government handouts at key moments in his rise to the top. They cite the techno-authoritarian financier and technologist Peter Thiel twice, criticizing him in similar terms. They do appreciatively cite the libertarian economist Tyler Cowen, who advocates for what he calls “state-capacity libertarianism,” a vision which shares a lot with the vision of Abundance. Nonetheless, they see their primary interlocutors as progressives.

Yet there is considerable overlap between the way Abundance and the Silicon Valley right use science fiction. Musk dreams of building robots, self-driving cars, Mars colonies. He speaks of the stakes of politics in grand, civilizational terms. Thiel loves Heinlein, and the PayPal founder was inspired by Neal Stephenson’s sci-fi-ish thriller Cryptonomicon. For his part, Andreessen was a Heinlein fan in his youth, and he remains a fan of the genre.

The strand of science fiction these technologists extol tends to emphasize human ingenuity, proffering optimistic stories in which small smart groups radically change the future for the better. In Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves (Morrow, 2015), the billionaire entrepreneur Sean Probst—who made his fortune mining asteroids—saves humanity from extinction without official authorization. In his Termination Shock (HarperCollins, 2021), Texas billionaire T. R. Schmidt sidesteps a gridlocked American government, launching a unilateral geo-engineering scheme, injecting sulfur into the stratosphere, to cool the planet. In these stories, decisive elites win the day.

If our goal is to produce and deploy solar panels fast, we might wonder whether humans need to be part of the mix at all. If climate change is a true emergency, an army of Tesla-manufactured Optimus robots might be just what we need. If we do not have enough doctors, well, Google’s AMIE artificial intelligence is reportedly demonstrating greater diagnostic accuracy and superior performance than real doctors in some circumstances.

What Klein and Thompson ultimately share with their Silicon Valley counterparts is a faith in intelligence and ingenuity to solve even the trickiest problems. The difference is that the Silicon Valley vision doesn’t have much regard for government. The most useful thing the government could do is to get out of the way of the builders and makers, the robots and the GPU clusters. Get rid of the regulations, and the future will take care of itself.

By contrast, Klein and Thompson are liberals, seeing a positive role for government. But they share the view that government needs to get out the way—and out of its own way, in particular. Past policymakers were not wrong to implement the policies they did, they tell us. Those policies, especially environmental and consumer protection policies, were appropriate to their time and place, and they even did a lot of good. We have simply failed to make rational updates. Ralph Nader was a hero, but his populist approach to consumer protection might now be a barrier to progress. (Weirdly, even Nader wrote the only half-ironically titled political fable, Only the Super-Rich Can Save Us!)

The question becomes what kind of individual or collective agent can enact changes comparable to—or even greater than—the mobilization for World War II.

The true hero of Abundance may be the empowered “bottleneck detective,” a figure who does in practice what Elon Musk does only in his imagination: thinking in terms of systems to rebuild irrational government processes along more rational and efficient lines. Sometimes, increasing supply requires more regulation, sometimes less. The bottleneck detective will get to the heart of the matter. It’s a metaphor for government that, to borrow the Apple slogan, just works—competence porn for liberals.

The science-fictional figure that this vision most recalls isn’t the billionaire asteroid-miner but rather the Wallfacers of Cixin Liu’s brilliant 2008 novel The Dark Forest (Chongqing Publishing House). In that novel, the Wallfacers are four individuals chosen by the United Nations to stave off a looming alien invasion, and they’re given the resources to do literally anything they want, because their alien opponents, the Trisolarans, are able instantly to read all human telecommunications but cannot read minds. Wallfacers are figures of genuinely planetary power, able to marshal the world’s resources at will. Of course, The Dark Forest is a novel by a Chinese science fiction writer, but the figure of the Wallfacer seems to me to be a figure for the possibility of planetary state capacity.

This is a heroic science-fictional vision, but it risks being at odds with democracy, elevating experts over stakeholders. Klein and Thompson might counter that the bottleneck detective is a civil servant, not an unchecked potentate. But as Klein and Thompson repeatedly note, liberal governance requires that liberals actually deliver on their promises. What’s the point of voting for a Democrat if they can’t get anything done, even in the bluest of blue states?

They celebrate Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro as a positive counterexample. In 2023, Shapiro rebuilt a collapsed section of I-95 in just twelve days. Shapiro, we’re told, “gets stuff done.” But is this the inspiring story Klein and Thompson think it is? Shapiro declared an emergency and suspended normal rules. There was no dispute about the goal, and Shapiro made it a personal priority.

Is this the power we want to invest in our chief executives? Is the model of routinized-state-of-exception coherent? And what happens if, well, the other side takes power?

Both left and right imagine a post-scarcity future of automated production, AI, and little need to work. Yet their ultimate visions of political economy are radically different. In Fully Automated Luxury Communism, job loss is the point; because we own the means of production together, we all benefit. By contrast, in the future Elon Musk hopes to build, there is no public ownership. Universal Basic Income supports the jobless but the jobless do not have effective control of anything.

Kim Stanley Robinson bets on the UN-backed Ministry of the Future, mass protests, rogue eco-sabotage, and new technologies. Neal Stephenson centers wildcat CEOs who bypass slow-moving bureaucracies, taking the initiative to do what must be done by themselves.

Klein and Thompson pin their hopes on the hyper-competent bottleneck detective, a metaphor for a refurbished liberal state capacity. This is not, to my mind, a fully satisfying science fiction story. It’s a solution that assumes its successful outcome, rather than telling us how to build the coalition to get from here to there. (But to be fair, I am not sure I can tell a better story.)

If you’ve built enough consensus to dependably get things done, to weather the setbacks and reversals that befall all political projects, the war against those who oppose abundance will have already been effectively won. And so, if Klein and Thompson want a liberalism that builds, they may need first to imagine a liberalism that builds solidarity.