Before she had Lady Liberty “lift my lamp beside the golden door” as she welcomed those “huddled masses yearning to breathe free”—to quote “The New Colossus,” inscribed on a plaque at the Statue of Liberty—Emma Lazarus drew inspiration from earlier bearers of light. In 1882, she published two poems celebrating the Maccabean warriors whose courage is commemorated every year on Hanukkah, which begins this year on Sunday evening, December 14.

Per Jewish legend, the Maccabees, freedom-fighting ancient Judeans who defeated the mighty Seleucid-Greek empire in 164 B.C.E., discovered, amidst the ruins of battle-bruised Jerusalem, a small jar of oil that miraculously lasted eight days, just enough time for the recovering Temple priests to produce a new batch. Ever since, Jews across the globe have been lighting a hanukkiah, an eight-branched menorah, or candelabra, in commemoration of the warriors’ courage, and how they brought the light of liberty to their fellow Israelites, seeking to practice their faith without fear.

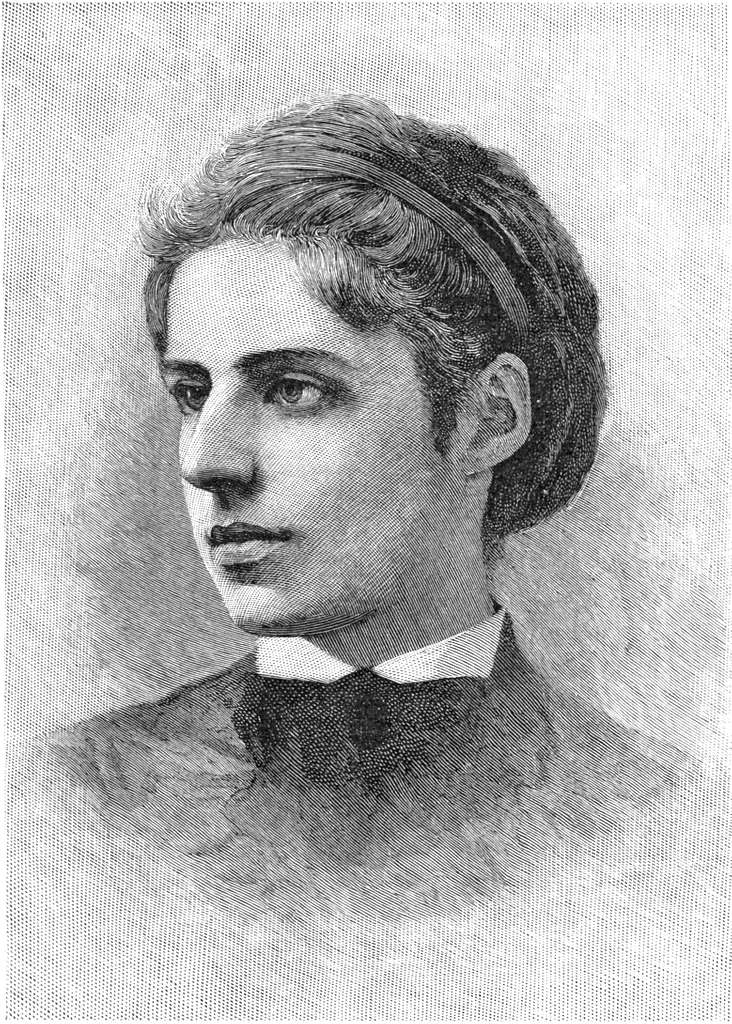

Emma Lazarus’s pride in millennia-old Jewish stories was, in light of her background, unexpected. Born in New York in 1849 to an assimilated Sephardic Jewish family, she observed Christmas and spent Friday evenings not in synagogue but at the elegant salons of Richard and Helena Gilder, the editor and illustrator of Century magazine. The prolific and widely admired writer and translator, whose professional circle included Ralph Waldo Emerson and James Russell Lowell, couldn’t help, however, but notice the Jew-hatred in the ether. “Within recent years,” she observed in Century, in words that read like today’s headlines, “in our schools and colleges, even in our scientific universities, Jewish scholars are frequently subjected to annoyance on account of their race…. In other words, all the magnanimity, patience, charity, and humanity, which the Jews have manifested in return for centuries of persecution, have been thus far inadequate to eradicate the profound antipathy engendered by fanaticism and ready to break out in one or another shape at any moment of popular excitement.”

Years after Emma’s death at age thirty-eight, her own sister, Annie Lazarus Johnston, who had converted to Anglican-Catholicism, denied a publisher’s request to publish Emma’s Jewish poems. In a 1926 letter, she explained her reasoning: “There has been a tendency on the part of the public to over emphasize the Hebraic strain of her work, giving it this quality of sectarian propaganda, which I greatly deplore, for I consider this to have been merely a phase in my sister’s development, called forth by righteous indignation at the tragic happenings of those days. Then, unfortunately, owing to her untimely death, this was destined to be her final word.”

Her sister’s post-facto protesting aside, even in her young adulthood, Lazarus discerned the need for Jewish political renewal and the protection of her coreligionists’ liberties. Inspired by George Eliot’s proto-Zionist Daniel Deronda (1876) and horrified by a wave of pogroms in Russia, she sensed the need for modern Maccabees to arise. The “Feast of Lights” (1882) depicts the menorah as a metaphor for the splendor of the Maccabean spirit she sought to write into existence:

Kindle the taper like the steadfast star

Ablaze on evening’s forehead o’er the earth,

And add each night a lustre till afar

An eightfold splendor shine above thy hearth.

Clash, Israel, the cymbals, touch the lyre,

Blow the brass trumpet and the harsh-tongued horn;

Chant psalms of victory till the heart takes fire,

The Maccabean spirit leap new-born.Remember how from wintry dawn till night,

Such songs were sung in Zion, when again

On the high altar flamed the sacred light,

And, purified from every Syrian stain,

The foam-white walls with golden shields were hung,

With crowns and silken spoils, and at the shrine,

Stood, midst their conqueror-tribe, five chieftains sprung

From one heroic stock, one seed divine.Five branches grown from Mattathias’ stem,

The Blessed John, the Keen-Eyed Jonathan,

Simon the fair, the Burst-of Spring, the Gem,

Eleazar, Help of-God; o’er all his clan

Judas the Lion-Prince, the Avenging Rod,

Towered in warrior-beauty, uncrowned king,

Armed with the breastplate and the sword of God,

Whose praise is: “He received the perishing.”They who had camped within the mountain-pass,

Couched on the rock, and tented neath the sky,

Who saw from Mizpah’s heights the tangled grass

Choke the wide Temple-courts, the altar lie

Disfigured and polluted—who had flung

Their faces on the stones, and mourned aloud

And rent their garments, wailing with one tongue,

Crushed as a wind-swept bed of reeds is bowed,Even they by one voice fired, one heart of flame,

Though broken reeds, had risen, and were men,

They rushed upon the spoiler and o’ercame,

Each arm for freedom had the strength of ten.

Now is their mourning into dancing turned,

Their sackcloth doffed for garments of delight,

Week-long the festive torches shall be burned,

Music and revelry wed day with night.Still ours the dance, the feast, the glorious Psalm,

The mystic lights of emblem, and the Word.

Where is our Judas? Where our five-branched palm?

Where are the lion-warriors of the Lord?

Clash, Israel, the cymbals, touch the lyre,

Sound the brass trumpet and the harsh-tongued horn,

Chant hymns of victory till the heart take fire,

The Maccabean spirit leap new-born!

“The Banner of the Jew,” published that same year and steeped in biblical allusions, sought to spark the courage of those in support of the Jewish nationalistic cause:

Wake, Israel, wake! Recall to-day

The glorious Maccabean rage,

The sire heroic, hoary-gray,

His five-fold lion-lineage:

The Wise, the Elect, the Help-of-God,

The Burst-of-Spring, the Avenging Rod.From Mizpeh’s mountain-ridge they saw

Jerusalem’s empty streets, her shrine

Laid waste where Greeks profaned the Law

With idol and with pagan sign.

Mourners in tattered black were there,

With ashes sprinkled on their hair.Then from the stony peak there rang

A blast to ope the graves; down poured

The Maccabean clan, who sang

Their battle-anthem to the Lord.

Five heroes lead, and following, see,

Ten thousand rush to victory!Oh for Jerusalem’s trumpet now,

To blow a blast of shattering power,

To wake the sleepers high and low,

And rouse them to the urgent hour!

No hand for vengeance—but to save,

A million naked swords should wave.Oh deem not dead that martial fire,

Say not the mystic flame is spent!

With Moses’ law and David’s lyre,

Your ancient strength remains unbent.

Let but an Ezra rise anew

To lift the Banner of the Jew!A rag, a mock at first—erelong,

When men have bled and women wept

To guard its precious folds from wrong,

Even they who shrunk, even they who slept,

Shall leap to bless it, and to save.

Strike! for the brave revere the brave!

In 1883, fourteen years before Theodore Herzl held the first Zionist Congress, Lazarus published Songs of a Semite, which included “The Banner of the Jew,” and founded the Society for the Improvement and Emigration of East European Jews, soliciting financial support for Jewish settlement in the Holy Land. She also composed a series of fifteen essays in The American Hebrew newspaper, later published together as An Epistle to the Hebrews, arguing for the return of the Jewish people to their ancestral homeland. Her Jewish identity did not detract from her Americanism.

That same year, she composed “The New Colossus” for an auction to raise money for the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. That poem has gone on to great fame, of course, while her Jewish poems—suppressed by her sister—have been forgotten. One hopes that those who celebrate Hanukkah, and those who celebrate America, will forget them no more.