One of the central tensions of American life thrums in the double meaning of “identity.” On the one hand, the word refers to a unique, irreplaceable, individual self, which we are summoned constantly to reveal and cherish. On the other, “identity” refers to the demographic categories by which we are linked to other examples of our types. Much of our contemporary talk about “identity” shuttles between proud affirmations of membership in groups and anxious insistence on our uncategorizable personal singularity. We long for connections and roots; we long to break free of tradition and cliché.

It demeans our sense of originality, so vital to our self-worth, to appear to be merely a generic instance of a collective, to find ourselves saying the things that its members always say, to be what Millennials call “basic” or Zoomers call “cringe.” Yet we know, however much we resist taking on the fullness of that knowledge, that we are powerless to invent out of our own heads the right kind of life. In order to be anything at all, let alone to be ourselves, or to become who we might be, we need to belong to categories that embarrass, trouble, and sometimes horrify us.

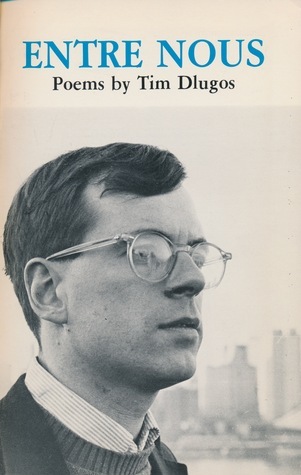

Few American writers address this tension as thoughtfully, playfully, and helpfully as Tim Dlugos (1950-1990). Although Nightboat Books has published Dlugos’s collected poems, edited by his friend and fellow poet David Trinidad (who is now, with Samuel Ernest, a doctoral student in religious studies at Yale, preparing for publication the poet’s essays and correspondence), Dlugos is almost unknown to literary critics and scholars, and awaits a wider readership. He is only now beginning to be appreciated as a central poet who, in his brief career, brought to bear the resources of post-war American poetry to consider his membership in two entangled identities, as a gay man and as a Christian.

There is nothing new, of course, about poetry inspired either by male homoeroticism or spiritual longing—and nothing new about poetry that combines these themes. Poets from St. John of the Cross (“oh living flame of love”) to Hart Crane and Robert Duncan remind us of that self-evidence. But spirituality and sexuality, as individual experiences of ecstasy or anguish, are not the same as religion and community, as collective forms of life, transpersonal patterns of practice and speech. If our pursuits of divine and human love can, at times, seem to be isolating, even anti-social, experiences that withdraw us from the everyday world, they are also, inevitably, shaped by our inheritances from and membership in concrete, specific communities. Dlugos’s poetry, along with his essays, short stories, and sermons, offer a precious consideration of how two such groups, gay culture and the Christian church, might relate to each other—and how both invite their members, and all of us, to ponder “identity” anew.

During his brief lifetime, Dlugos—who can be seen reading his poetry in 1977 here—was known to small sets of friends and readers as a minor poet in the vein of the New York School, characterized by a breezy combination of pop-culture references, semi-absurdist shifts in tone and topic, and cliquish distance from the literary mainstream. He was familiar to a slightly larger audience as a journalist covering the gay community, focusing particularly on its relationship with Christianity, for the magazine Christopher Street and its associated newspaper New York Native. Among a somewhat overlapping circle, he was a fixture of New York’s Anglo-Catholic demi-monde, and a seminarian in training to be an Episcopal priest at Yale Divinity School. In his last years, dying of HIV/AIDS, Dlugos divided his time among poetry, theological study, and caring for other gravely ill people as a hospital chaplain.

Dlugos’s poetry, along with his essays, short stories, and sermons, offer a precious consideration of how two such groups, gay culture and the Christian church, might relate to each other—and how both invite their members, and all of us, to ponder “identity” anew.

For most of his life, Dlugos had wanted to be a priest. Raised Roman Catholic in Massachusetts to parents of Polish descent, in high school he had been a member of the Catholic Vocation Club, which prepared boys to enter the clergy; a week before graduation he joined the De La Salle Christian Brothers as a postulant, on track to join the priesthood. During his college years (at La Salle College in Philadelphia), however, after what he described as “the most grace-filled moment” of his life—an affair with a male classmate—he left the Brothers and became president of the college’s gay student group. He then moved to Washington D.C., and became involved both in gay poetry circles and in Ralph Nader’s Public Citizen group, before heading to New York in 1976 and starting work for gay media.

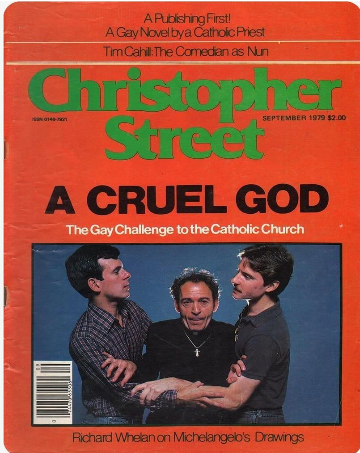

Much of his writing for Christopher Street and New York Native documented how gay Christians, such as the members of Dignity, the leading gay Roman Catholic organization, were fighting for a place as gay men in the church. Dlugos was not shy about discussing his own struggles. “A Cruel God,” his 1979 cover story for Christopher Street on gays in the Catholic church, not only explored his personal crisis of faith but showed him on the cover, in a melodramatic allegory of a priest tearing two men apart. In that article, Dlugos appeared to despair about whether the church could ever make room for gay men, and whether his own faith could ever find a home.

That search led him, as it led many other gay men, into the Episcopal church, and specifically its Anglo-Catholic current. A sensibility rather than an institution, Anglo-Catholicism links a set of parishes that draw on pre-Reformation, and pre-Vatican II, aspects of Catholic theology and liturgy, while retaining a Protestant identity distinct from what its members pointedly call Roman Catholicism. Its network of parishes includes The Church of St. Mary the Virgin, on W. 46th Street in New York, known to its congregants and fans as “Smokey Mary’s” for the quantities of incense used in its masses (in the mid-eighties, Dlugos lived in its rectory).

In a 1984 story for the New York Native, “Where I Hang My Cassock,” and in other stories for gay media, Dlugos wrote about finding religious community in an Episcopal parish, after years of occasional, furtive, ambivalent attendance at Roman Catholic Mass. Here he could find what “I had almost given up hope for ever finding … a vast sense of relief … a context where I can participate as more than the loyal opposition,” fighting for change within the church. In a gay-affirming Episcopal parish with an Anglo-Catholic orientation, he could be a regular, unremarkable member.

That same year, he joined Alcoholics Anonymous. That AA and a return to regular Christian practice were closely connected in his life is hardly accidental or unique. AA, since its founding in 1935, has drawn from the language and practices of American Christianity to create a spiritually-flavored fusion of community-building and self-help. In his poetry and correspondence, Dlugos frequently evinced certainty that AA, along with the “blessed Mother,” had saved him from a self-destructive relationship to alcohol, and modelled for him what it would be like to have a religious practice and community in which he was not a marginal, agitating dissenter, but part of the crowd.

As Dlugos was finding his way towards an increasingly unembarrassed membership in, and taking up the responsibilities of speaking on behalf of, his communities, the gay world in which he lived and wrote was being devastated by AIDS, which became a key theme of his late work, as he grappled with his own diagnosis and looming death. His most powerful and enduring poem—one of his last—is “G-9” (1989), a meditation on his time in an AIDS ward, and on the ambiguities of religious belonging. Spanning several pages, it connects dead and dying friends, his own approaching death, and a recurrent worry about his reliance on the clichés of AA and ordinary Christian religiosity to get through each day. One of the great literary witnesses to the American AIDS crisis, it is also a subtle, touching, and sometimes funny spiritual struggle to make peace with our inescapable dependence on “corny” formulas. In one passage, Dlugos considers AA’s vaguely theistic injunction to, as the Twelve Steps put it, “make a decision to turn their will and lives over to the care of God as they understood Him.”

turning everything

over to God “as I understand

him.” I don’t understand him.

Thank God I read so much

Calvin last spring; the absolute

necessity of blind obedience

to a sometimes comforting,

sometimes repellent, always

incomprehensible Source

of light and life stayed with me.

God can seem

so foreign, a parent

from another country,

like my Dad and his own

father speaking Polish

in the kitchen …

Dlugos in this passage invokes, then mocks, AA’s formula, before deepening it with a turn to John Calvin’s theological insistence on God’s total sovereignty over our lives, and its logical conclusion in the doctrine of predestination, according to which God decided before the beginning of time who would be saved and who would be damned. This teaching terrifies and disgusts many Christians, for whom it seems to negate the very idea of a loving Creator seeking his children’s salvation. Juxtaposing AA’s vague, facile, and cheery notion of a Higher Power with Calvin’s “repellent” God, Dlugos does not, however, reject either.

AA and Calvin are both, he suggests, somehow right—we are dependent on God, whom we understand so little and so fearfully, and we are no less dependent on the inadequate, mockable, and disturbing formulas handed down to us from institutions and theologians. What makes this dependence bearable in the poem is Dlugos’s analogizing it to his childhood incomprehension of his father and grandfather speaking together in a foreign language. It is as though the God we know as a father, or Church we know as a mother, has behind it a still more ancient and mysterious ancestor, whose voice we can hear but whose speech we cannot understand.

From the perspective of an artist or intellectual, AA and religion alike can seem hopelessly dependent on shallow clichés and bits of pre-digested wisdom that might be, one thinks, good enough for some average slob, but not for a unique, thoughtful individual like me. Indeed, Dlugos wrote in a 1987 letter that his experience of alcoholism, and of homosexuality, had long been inseparable from a feeling of “grandiosity,” that he was somehow different from, and superior to, the people around him, “more intelligent, more tasteful, more interesting.”

It is as though the God we know as a father, or Church we know as a mother, has behind it a still more ancient and mysterious ancestor, whose voice we can hear but whose speech we cannot understand.

He did not say, but might have added, that the vocation of the priest or poet can also, all too often, be founded on a similar sense of superiority and contempt for normalcy. A crucial aspect of Dlugos’s spiritual and artistic path, then, was to discover how his experiences—and even his desire to be dazzlingly unique—were what made him like everyone else, and how, in light of that discovery, he might reconcile the intensely intimate with the ordinary, common, and clichéd.

Toward the end of “G-9,” as Dlugos imagined his own death, he returned to the problem of “corny” religious speech:

I wish I had a closer personal

relationship with Christ,

which I know sounds corny

and alarming …

… maybe

my head will be shaved

and scarred from surgery;

maybe I’ll be pencil-

thin and paler than

a ghost, pale as the vesper

light outside my window now.

It would be good to know

that I could close my eyes

and lean my head back

on his should then,

as natural and trusting

as I’d be with a cherished

love.

Here again the poet finds that he must rely on what he takes to be an embarrassingly flat, platitudinous expression from the collective repertory of religious talk. After critiquing it, and distancing himself from it—saying it sounds not only “corny,” a bit of spiritual kitsch, but “alarming,” perhaps for its associations with evangelical Christianity and the Religious Right—he approaches it once more, giving it a body, making it specific, real, and loved. Just as the “Higher Power” of AA became first Calvin’s threatening God and then a loved if incomprehensible parent, so here does Christ pass from the topic of Christianized therapy-speak (“personal relationship”) into a distinct person who, like a lover, or indeed a parent, will hold us as we die. As Samuel Ernest observes, here “ cliché transcends itself. It’s what made Allen Ginsberg call the poem ‘one of the most humane, heartfelt, sincere poems I’ve ever read … one of the great poems of this part of the century.’”

Dlugos challenged himself throughout the last years of his life to overcome the notion, so destructive of religious belief, that there is a choice to be made between conventional forms on the one hand, and, on the other, authentic self-expression. His life as a gay man, and a gay writer, was similarly shadowed and vexed by the fear that, precisely because it put him in a category with other people, his sexuality might be a ticket to what he worried in a 1982 letter was literary “mediocrity.”

He insisted petulantly to his correspondent that “I don’t write gay poetry, any more than I write Catholic or New York (though some would disagree about that) poetry,” although indeed most of his writing was concerned with some combination of these topics, contexts, and audiences. Further, he lamented that the rise of the gay rights movement and the growth of a distinct urban gay culture had turned homosexuality from an edgy avant-garde phenomenon to a “bourgeois backwater.” While other writers for Christopher Street, like Andrew Holleran and Edmund White, celebrated the artistic effervescence of the gay movement (evidenced not least in their own novels), Dlugos, in private, felt at times that it was all going in the wrong direction, into “very steep … cultural decline.” He feared that identification with, and commitment to, a particular group made writers lose their individuality and imagination. A terror of being unoriginal, of being just another gay man, just another recovering alcoholic, just another Christian, was in tension for much of Dlugos’s life with a wish to belong, to be a part of a community of people like himself.

This uneasy combination of feelings runs through Dlugos’s relationship to his most important poetic inspiration, Frank O’Hara (1926-1966). A key figure in the New York networks that linked the abstract painters celebrated in ArtNews with avant-garde poets who supplemented their incomes writing art criticism, O’Hara was known for seemingly casual poems that imitate the rhythms and content of a certain kind of everyday talk, as well as campy (but not unserious) reinterpretations of the poet’s traditional role as prophet, such as his poem “A True Account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island.” As the mention of Fire Island might suggest, O’Hara, like many members of his literary and artistic networks, was homosexual. Many of his poems showcase stereotypically gay humor and interests. They often imply, but rarely directly state, romantic situations with other men and participation in tangles of homosexual friendship. They hardly ever touch on politics, let alone on gay liberation.

In the years after his death, as O’Hara was coming to be recognized as one of the major poets of the post-war era, his sexual identity could seem a stumbling block even to sympathetic critics. In an April 1977 column for Christopher Street, for example, Dlugos traced the spread of O’Hara’s influence a decade after the poet’s death, noting that he was increasingly recognized as “a tremendously important poet of this century,” thanks in large part to the work of the critic Marjorie Perloff—who worried, however, that O’Hara would be seen as just a gay poet, and went to great length, in conversation with Dlugos, to stress O’Hara’s connections to respectable, serious heterosexual poets like “[Rainer Maria] Rilke and [Guillaume] Apollinaire,” while downplaying his debts to “gay humor” or other homosexual poets, like W.H. Auden.

As Perloff, interviewed by Dlugos, framed the issue, O’Hara could be a major poet “squarely within an important stream” of the canon, as well as a homosexual. But this was possible only if his homosexuality were understood as an individual trait, a private quirk of sexual conduct. It could not be understood as a meaningful dimension of his writing practice, or his search for literary exemplars and interlocutors. O’Hara would appear, in the sort of interpretation Perloff disavowed, as a gay writer not because he happened to be homosexual, but because he took up his sexuality in such a way as to connect to a gay world, from the beaches of Fire Island to the writing of friend and fellow homosexual John Ashbery (1927-2017), or the painting of his sometime-lover Larry Rivers (1923-2002). In Perloff’s eyes, and in those of most critics of that era, it was as if one had to choose, not between being a great writer and being a homosexual, but between being a great writer and identifying with gay culture.

Dlugos admired, imitated, and joked about O’Hara, even as he sometimes feared that Perloff was right. “Frank O’Hara is THE great American poet and seer of this our century,” he wrote in 1973, “he should have been on tv.” One of Dlugos’s most popular early poems, “Poem After Dinner,” written that same year, recalls O’Hara’s Lunch Poems (1964):

some things never run out:

my poverty, for instance,

is never exhausted

sandwiches for dinner again

your blond hair, for instance,

even if we’re both exhausted

soothes me when we go outside

you and the forsythias

I get so excited

I think I’ll read the Susan Sontag article

in Partisan Review

I want to walk beside you in the drizzle

and say you can move in with me

tonight, right away, even though

this time they’ll probably evict me

and although I’m moving out in three weeks anyway

Like the Lunch Poems, “Poem After Dinner” presents itself as if it had been written in a spare moment, with an off-hand, occasional style, dashed off during or after a meal. But it has important formal elements. The lines of the first two stanzas all have roughly the same number of stresses, and repeat some ending words (“exhausted” and “for instance”) to create an expectation that they and other ending words might be repeated again. Both of these patterns are then upended in the third stanza, which alternates between short and long lines (the latter linked by a quiet off-rhyme “article … drizzle”), in which the speaker hesitates between the excitement of desire and a wish to calm himself down by reading something intellectual. This sets up the fourth stanza’s longer, rushed lines that convey, and then doubly undercut, the speaker’s fantasy of asking the man to whom the poet is addressed to move in with him.

The poem, read aloud, might sound like a spontaneous musing, but it has been carefully shaped and ordered to indicate a sequence of conflicting emotions—a typically O’Hara-esque strategy of studied désinvolture. Likewise, just as O’Hara peppered his poetry with references to friends, Hollywood icons, painters, and other writers, Dlugos here combines apostrophe to his friend/lover Tim with an ironically pretentious declaration about how he means to read Sontag (whom only a small number of readers in the know would understand as a queer icon; Sontag would not be “out” for another two and a half decades).

O’Hara was not Dlugos’s only model. Like his friend Donald Britton (1951-1994), whose poetry is back in print and gaining new attention, Dlugos took up many elements of John Ashbery’s poetry, such as his movement between sublime and slangy registers, and played with forms like the sestina. Ashbery, however, almost never acknowledged his homosexuality in his poetry, and eschewed comment on political topics, even in the midst of the Vietnam War or the AIDS crisis (some of Ashbery’s present-day admirers nevertheless strain to read him as a properly political writer). Dlugos, in contrast, learned to write poetry that both revivified traditional forms and commented on contemporary political issues, as in this 1980 sestina that mocked the politics around the word “queer.” Published only in 1993, in the literary magazine B City, the poem finds Dlugos in conflict with his friend and fellow poet Steven Hamilton, an early adopter of what would become an increasingly common stance of differentiating oneself from what was already seen as a gay community that had become too “normal” to be interesting:

When people ask, I tell them that I’m gay.

But there are people who will say, “I’m queer,

not gay!” like my friend Steven Hamilton.

He says that the word “gay” defines a movement

of disco-crazed drag queens and Castro clones.

“Queer” doesn’t imply the whole dumb sub-culture.Now Steven and I both are queer for culture:

poetry, dance, opera, the gay

party circuit, the friends who’d think it queer

not to appear at functions. The Hamilton

Beach toaster pops up. With a cat-like movement

I grab my toast and bolt it. I’m a cycloneof activity each morning. A clone

’s a fingernail cell grown inside a culture

jar. Fuck that. Morning elements: a nosegay

in a small vase, gift of a handsome queer,

the favorite coffee of Margaret Hamilton

steaming in my mug, the rapid movementof my eyes in sleep, the hasty movement

of my hands through my stubborn hair It’s Klon-

dike cold outside my little house, The Cultur-

al Council Foundation’s in the mail. Ga-

len Williams sends me Coda. It’s a queer

profession we are in, dear Hamilton.When I see Alexander Hamilton

on money, it requires the furtive movement

of my hand to my teary eye. Steve’s no clone,

but there’s still a resemblance. In this culture,

if Dad’s a politician, Sonny’s gay,

cf. Jack Ford and Randy Agnew. Queer,isn’t it? And Steven says he’s queer,

not gay. And he has never been to Hamilton,

Bermuda. And the perfect languid movement

of his cigarette makes me half-think he’s cloned

from a great actress, now-deceased. If Kulchur

Press puts out his book, will they call him gay

or queer? Neither. The movement of our culture

is away from dull gay Castro clones and toward Steven Hamilton.

Unlike O’Hara and Ashbery, Dlugos could speak to political and cultural questions within the gay (or queer) community, staging disagreements over the very words that should be used to define it. But he did so by drawing on O’Hara and Ashbery’s humor, making for example topical references to Spiro Agnew’s son, who allegedly had left his wife for a male hairdresser. While the poem ends by apparently rallying to his friend’s critique of an overly conformist gay community in favor of something more edgy and “queer,” Dlugos questions whether there really is such a difference between the ostentatiously anti-normative “queer,” on the one hand, and the supposedly boring, stereotypical “gay” “clone” on the other. The repetition of the words “gay” and “queer” throughout the sestina, punningly drawing out new meanings each time, undermines the dichotomy posited by his friend. So too does his joke that as a politician’s son, his friend Steven must be, like Randy Agnew, the son of a former vice president, “gay,” which is pretty “queer, isn’t it?”

The position suggested in the sestina—that gay culture is not after all as limited and dull as “queer” Steven Hamilton suggests, and that there is no clear division between a generative avant-garde and an apparently staid community—was the opposite of the one Dlugos took in his 1982 letter on the “mediocrity” of gay culture. Identification with the complex of sensibilities, tastes, and shared histories that composed gay identity in the late–twentieth century United States was, of course, the basis of much of Dlugos’s writerly life. It provided his themes, models, humor, references, patrons, friends, and venues for publications. Yet rather than seeing the gay world as the set of practices and forms by which he could become a writer at all, Dlugos, like many other writers in his circles, worried that he would miss out on the chance to have a proper reputation as a serious writer concerned with universal themes.

Dlugos seems to have been no less concerned about being categorized as a (merely) Catholic writer. While from the mid-seventies on he wrote, with whatever private reservations, largely for gay audiences about gay themes, he was reluctant to put his struggles with the church, his longing for and despair of finding an ecclesiastical home, into (even his unpublished) poetry. In part, perhaps, he was not yet able to imagine how Christianity could be reconciled with homosexuality, which he could begin to accomplish only after joining AA and an affirming church.

Christianity and homosexuality could certainly seem to be in conflict. But in another sense both aspects of Dlugos’s life posed a common problem for his career as a poet. While major critics of post-war poetry like Perloff, Helen Vendler, and Harold Bloom celebrated the idiosyncratic and half-ironic spirituality of (by coincidence, homosexual) poets like Ashbery (particularly his Three Poems) or James Merrill, and while the vatic rants of Allen Ginsberg are familiar to every American reader, there has been little space since T.S. Eliot for American poets wrestling earnestly with conventional Christianity. Forms of private, goofy, harmless occultism, or of leftist cosmopolitan political visions, can be accepted by polite critics as inoffensive expressions of a poet’s singularity. But a writer who grapples with traditional belief, who persists despite doubts and criticisms in identifying as a Christian like any other, can seem to secular critics to be, as Dlugos put it, “corny” and “alarming.”

There has been little space since T.S. Eliot for American poets wrestling earnestly with conventional Christianity.

Dlugos was able to begin writing what could be called Christian poetry only in the early eighties, as he began to face his alcoholism and accept that he needed to join a church in which he could be a full and open member rather than “loyal opposition.” It was a slow journey. An unpublished poem from the spring of 1981, for example, just before the gay community became aware of the AIDS crisis, finds Dlugos dealing with themes of mortality, love, and the purpose of writing, but still without any clear engagement with Christianity. Despite the obscenity in the first line, repeated throughout the poem, it’s a gentle, sad lyric, carried along on the semi-conversational rhythm of mostly four-beat lines that in their repetitions become mildly incantatory.

My friends say it takes me fucking forever

to get my work done and they’re right.

I write in my head and the work is completed,

finito. Transcription’s a drag.

I say to myself I’d rather be fucking,

forever’s a long time and I’ll be dead

for that long some day, not far away

as time goes, which is all time does,

no chance to say goodbye as the people

you care about enter the fucking Forever

or Great Beyond, however you say it

it still makes me angry or anguished, though not

for myself, and certainly never “resigned”—

I gave up that worry the first time death brushed me

and never look back to the time when I looked

to the future with fear. I look to the page

as it fills up with words, and though I’m forever

fucking around, once I get started I write

’til it’s finished. There’s no such thing as deathless

verse, but still it’s a comfort as long as my body

holds out to be making a work I can live in

today and enjoy it; and fuck posterity,

when they’re around I’ll be gone to wherever,

hopefully fucking forever with someone

who looks a lot like you.

Here there is hardly any hint that Dlugos seriously hoped—as he did—for an afterlife, much less a Christian one, and still much less a Heaven in which the conflicts over homosexuality that have run through the earthly history of Christianity are transcended in a union of human and divine love. Dlugos was not yet ready to integrate his religious faith with the persona and style of poetry he had inherited from O’Hara and Ashbery, although he had learned to bend the latter’s unpolemical, semi-ironic tone to accommodate explicitly gay and political themes.

A year later, in 1982, Dlugos was beginning to put his religion into his poetry, at first as a joke:

The Mineshaft, Friday night:

“Just Men”

if I can find ten

I’ll spare this city

The pun by which Dlugos’s search for sex in an all-male gay bar can be read in the same terms as Abraham’s search for ten “just men” in Sodom conceals, in its humor, a deeper analogy between the sadness of a desperate search for love (Dlugos’s diaries, letters, and poetry find him in those years regularly heart-broken over a succession of short-lived romances) and the patriarch’s anxious wish to divert God’s wrath. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the biblical story of Sodom, after all, is that (like Moses in later conflicts with God) it is Abraham, rather than God, who seems to show mercy and care for the members of his common world. The deity presents himself as once again—after the Fall, after the Flood—appearing to condemn, punish, destroy. Yet perhaps God was pleased that Abraham questioned him, and asked him to reconsider his criteria for judgment, then went off into Sodom full of worried love.

Later that year, Dlugos addressed another apparently comic poem, “Psalm,” to God. Parodying Psalm 42 (“as a dear pants for water …”), it declares:

Like a Doberman longs for an enormous field

big enough to run across as hard and as far

as it can … so my soul

longs for You, Lord, for the vast amused amazement

of your grace …

The poem is not one of his triumphs, and the Doberman line is not very funny. But the poet now is joking to God rather than about God, or about anything but God. And he hopes to find God in the “amused amazement” of grace. What does it mean for grace to have an amused amazement, when logically it would be God, the bestower of grace, or the poet, who receives it, who should be amused and amazed? And isn’t amusement a strange emotion to encounter here? It seems that Dlugos is inviting us to imagine grace, as it pours from God to man, to be itself both sublime and hilarious, a kind of wonderful shared joke.

The AIDS crisis, which broke out just as Dlugos made this critical turn in his writing and life, would not seem to be an opportune moment for the deployment of a sense of humor. Much of Dlugos’s writing from his period consists of scholarly papers for his divinity school classes at Yale, or correspondence with religious officials such as his bishop, Richard Grein. In 1989, a year before his death, he wrote to Grein of his work as a hospital chaplain-in-training, for example, that he was forced to accept that “it’s not a sign of failure to simply be present and share the pain of people in situations where a positive attitude won’t change the terrible things that are happening to them. I’m learning, too, that my own feelings of powerlessness and inadequacy don’t really matter, what counts is that I can turn things over to God and then show up for people, whether or not it makes me feel like a pastoral success.”

Dlugos’s correspondence finds him trying, in the vanishingly small amount of time left to him, to understand how to trust God and work effectively to show God’s love in the world, amid the disasters of AIDS. How could he make sense of his utter helplessness—his vulnerability to addiction and to despair, his continual need for support from traditions and commonplaces that could seem pathetic, clichéd, and absurdly inadequate to the challenges he faced—without giving in to mere fatalism?

The question does not seem to invite comedy. But reflecting on these problems in the AIDS ward of “G-9,” Dlugos describes turning control over to God as “pack[ing] up all / my care and woes” onto the “conveyor belt” towards Heaven. This is already a comic image, and its silliness is deepened as the poet observes that this makes him feel like “Lucy on TV.” Rather than watching his worries pulling away from him into God’s providence, Dlugos-as-Lucy scrambles flailingly to hold on to whatever cares he can, while they are torn from him, like his fleeting life.

In his late work Dlugos shows how the pat forms and phrases made available to us by Christianity, AA, or gay life—or any of our communities, cultures and faiths—are as necessary as they are poignantly useless, indeed mockable, without an infusion of comic grace. The ways we remind ourselves that we’re not in control but are nevertheless bound to do what good we can seem pathetically kitsch, clichéd, and inadequate. It is the task of the poet, and of the priest, to make them fresh and credible, and to help us encounter the “vast amused amazement” that may redeem us.