For many politicos and pundits, Mitt Romney’s ascendancy to the top of Republican presidential ticket has marked the high point—so far—of the much-hyped “Mormon Moment.” Yet is Mormonism’s coming of age story really the most important development in American religion and politics during this election cycle? Hasn’t Catholicism played an even bigger role?

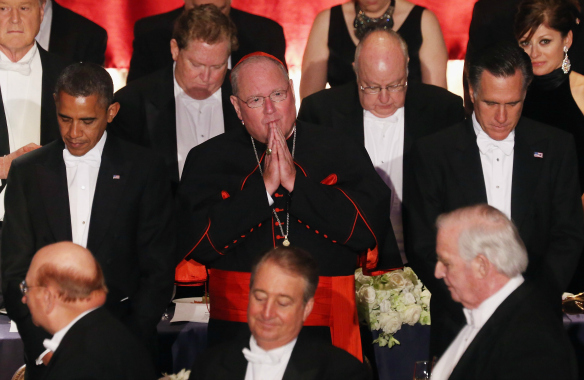

There is certainly plenty of evidence that 2012 is more of a “Catholic Moment” than a Mormon one. After all, more than Mormons, American Catholics have come to occupy high governmental positions once only reserved for “WASPs.” Catholics today dominate the Supreme Court (six of nine justices, with three Jews filling out the bench). The current and immediate past Speakers of the House are practicing Catholics, as are both vice-presidential nominees—a historic first. Also while the number of American Catholics continues to grow, Protestants now account for fewer than half of all Americans, and even white evangelicals are diminishing in number.

Yet if these obvious markers—political prominence, demographic heft, even social cachet—are legitimate points of pride for American Catholics who recall their perennial outsider status in “Protestant America,” they are also the least important aspects of the Catholic Moment, if indeed that’s what this proves to be.

Rather, it is the substance of Catholicism that is having its day, thanks mainly to the election’s focus on the economy, the attendant debate about the balance between the American common good and the American ideal of individualism, and how to translate this balance into actual tax and spend policies. From the social justice tours of the “Nuns on the Bus” to fights over Paul Ryan’s budget plans, classic concepts from Catholic social teaching are now invoked with a regularity that must astound Catholic theologians. Instead of talking to glassy-eyed undergrads in college lecture halls, Catholic scholars and politicians are debating the finer details of papal encyclicals—concepts such as “subsidiarity and solidarity” and “prudential judgment”—on national cable news shows.

Indeed, what is reflected in all of the debates emerging from the 2012 presidential contest is a profound concern about who we are as a nation: Are we a mutually supportive community, or are we a collection of individuals acting out of self-interest? Addressing this question will require overcoming the endemic polarization of American politics by finding ways to engage those who hold opposing views and recovering an ability to translate compromise into public policy.

In this endeavor, Catholics should take real pride that no matter who wins on November 6, their tradition can provide the vocabulary for this much-needed national conversation. To be sure, many of these concepts are found in other religious and philosophical traditions. But Catholicism benefits from having organized and articulated these ideas so diligently over the centuries. What’s more, Catholicism can today boast of having an unprecedented number of public exponents of the faith—both in politics and in the church’s own hierarchy—who can speak to the broader American society, and can speak on behalf of a growing Catholic community of Americans.

Yet embedded in this potential “Catholic Moment” is a problem, or more accurately, a paradox: Just as the nation debates a vision of the common good that is Catholic at its core, and just as our politics demands Catholic concepts to translate that communitarian ethos into policy, Catholic leaders and Catholic voters can’t agree on what they think these Catholic teachings actually mean. Nor can they agree on how, or whether, those teachings might apply to the public square.

THE MOST OBVIOUS FLASHPOINT for this debate is the candidacy of Mitt Romney’s running mate, Congressman Paul Ryan. Ryan is a life-long practicing Catholic. He is also an acolyte of Ayn Rand, the libertarian philosopher who argued that selfishness should be considered a virtue. Ryan has sought to baptize Rand’s views (she was an atheist who rejected both charity and restrictions on abortion) by presenting Catholic social teaching on “subsidiarity,” for example, as a kind of “federalism” that demotes the role of the state and diminishes the idea of solidarity.

This strategy has been picked apart by any number of Catholics, most effectively (and charitably) in “On All Our Shoulders,” a statement signed by large group of leading, and politically diverse, Catholic scholars and theologians, and released the night before two Catholics squared off in the vice-presidential debate. The signatories thoroughly deconstruct Ryan’s interpretation of Catholic social teaching and challenge those who would turn Catholicism’s preferential option for the poor into a preferential option for the well-to-do. Michael Sean Winters noted that even the title of the statement “is an obvious reference to [Ayn] Rand’s famous book Atlas Shrugged. Atlas, you will recall, carried the world on his shoulders and the Catholic theologians who drafted this statement wish to suggest that all of us, as a group, are responsible for carrying the world on our shoulders.”

Still, while the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) has criticized Ryan’s budget as morally flawed, a number of bishops have also defended Ryan, praising his emphasis on eliminating the deficit by cutting social welfare programs and reducing the tax burden for the wealthy. “Vice Presidential Candidate Ryan is aware of Catholic Social Teaching,” Ryan’s bishop in Wisconsin, Robert C. Morlino, wrote in August. “[He] is very careful to fashion and form his conclusions in accord with the principles [of Catholicism]. Of that I have no doubt.”

The backing of bishops like Morlino allows Ryan to argue that the Catholic case against his budget is not open-and-shut. For some of Ryan’s Catholic supporters, “prudential judgment” in decision-making means that emphasizing long-term deficit reduction over short-term social programs is itself a means of caring for the poor in a sustainable way. “Jesus tells us very clearly that if we don’t help the poor, we’re going to go to hell. Period,” Philadelphia’s Archbishop Charles Chaput, an outspoken conservative, said recently. But, he added, “Jesus didn’t say the government has to take care of them, or that we have to pay taxes to take care of them.”

Chaput’s statement is very much in line with Ryan’s oft-expressed view that Catholicism’s preferential option for the poor “does not translate into a preferential option for bigger government.” Yet that’s also not what Catholic social teaching and its proponents are advocating. The church’s social magisterium is not an either/or choice between two party platforms or ideologies. What’s more, Catholic social teaching makes clear that if government at the local level is not protecting the vulnerable, then government at a higher level must do so. As the Reverend Thomas Reese put it, “Prudence is not an option to do nothing. That’s what the scribes and Pharisees did when they walked by the man lying by the side of the road.”

A related challenge to Catholicism’s public witness stems from the regular invocation of the category of “intrinsic evils” as a shortcut through the maze of moral reasoning that voting requires. As the bishops of the USCCB write in “Faithful Citizenship,” their own guide for Catholic voters, “all issues do not carry the same moral weight and … the moral obligation to oppose intrinsically evil acts has a special claim on our consciences and our actions.”

The “intrinsic evils” the bishops are referring to are, of course abortion and euthanasia. The problem is that, according to official Catholic teachings, there are many other “intrinsic evils,” a term that simply refers to an action that is always and everywhere immoral. Torture is one such example. Masturbation is another. But the former receives scant mention, and the latter isn’t on any party’s political agenda, for or against.

On the other hand, cutting the safety net for the poor to balance the budget, or taxing the wealthy at a lower rate than the middle-class, is not intrinsically evil. Still, that doesn’t mean such policies are morally sound. “Somehow many of our bishops seem to have become convinced … that if something isn’t intrinsically evil, it’s necessarily less important, and we may not even be sure that the tradition holds it to be wrong,” as theologian Daniel K. Finn recently explained in Commonweal.

Moreover, ending abortion is more than a question of overturning Roe v. Wade. It’s also, or perhaps primarily, a matter of public policy—providing support for families and for women who decide to give birth, for instance—because even in a post-Roe world most states would keep abortion legal. What then? “Prudence,” Finn writes, “is regularly overused in addressing economic justice and underappreciated in discussing life issues. Thomas Aquinas taught that prudence is the virtue that allows us to take concrete action as we live out our moral principles.”

THE PREDICTABLE CONSEQUENCE of this unbalanced presentation of Catholic social teaching is that Catholicism winds up looking like a single-issue political lobby—the very thing the church’s leaders say the church should not be.

Look, for example, at what transpired during the vice-presidential debate between Biden and Ryan. When moderator Martha Raddatz, who otherwise received high praise for her performance, asked about Biden and Ryan’s shared faith, she posed the “Catholic question” this way: “I would like to ask you what role your has religion played in your own personal views on abortion?”

“What a lost opportunity!,” lamented Michael O’Loughlin at America Magazine. “I think Ryan and Biden both gave convincing, sincere answers,” O’Loughlin wrote. “But to limit the conversation about their Catholic faith to abortion is shameful. What about poverty? Immigration? Unions? The environment? Believe it or not, these are all ‘Catholic’ issues too.”

This gets us to the crux of the problem: The reduction of Catholic teaching by Catholics on both sides of the partisan divide to single issues means that Catholics won’t do politics well, or they won’t do it at all. And both outcomes loom.

The fallout from the split between “social justice” Catholics and “pro-life” Catholics—a dichotomy that makes no sense under traditional Catholic teaching—was evident in the bruising battle over the 2009 health care law. The Catholic Church has long believed that universal health care is a basic human right, yet the Catholic bishops eventually opposed Obama’s reform. This despite the fact that they won, in a dramatic last-minute negotiation, extra guarantees of a ban on taxpayer funding of abortions. But the bishops couldn’t take “yes” for an answer. Pro-life Democrats in Congress who delivered the abortion provision and the key votes for passage—and had provided the hierarchy’s best political leverage on the Capitol Hill in years—wound up on the bishop’s enemies list. Their ranks were halved in the 2010 midterms and could well be reduced again on November 6th.

Another sign of the church’s failure to foster a distinctively Catholic political vision is the sharp division among Catholic voters, with white conservatives, moderates, and liberals, as well as the growing number of Latino voters, all moving in different political directions for different reasons. Being a “swing voter” can, in some contexts, be a sign of political savvy. In other contexts, it is a symptom of political incoherence that leaves many American Catholics ready to throw up their hands and vote according to their own best interest—or, worse still, to not vote at all, as some on both the Catholic left and right are considering.

We are already witnessing a Catholic withdrawal from the public square, as some bishops threaten to shut down social service agencies, hospitals and universities in order to maintain a moral purity they say would be corrupted by taking government funds or accommodating government policies. If this occurs, the “Catholic Moment” could become a missed opportunity. Catholics are not Amish. The church believes Catholics have a mission in the world. Politics is part of that mission, and the Catholic tradition provides the means to carry out that mission. As the editors of America Magazine put it in an editorial earlier this year, “the Catholic conscience needs to remain engaged in the public forum out of our faith in the church as a ‘sacrament’ for the world.”

Today that sacrament is needed more than ever. At a time when prophetic denunciation is the preferred register of public discourse, when apocalyptic rhetoric substitutes for careful reasoning, when politics takes the place of religion, and nationalism the place of genuine faith, the Catholic tradition provides the moral language for a different approach. This Catholic approach emphasizes governing over campaigning, compromise over winner-take-all politics, and the common good over hyper-individualism.

Yes, this could well be, should well be, America’s Catholic moment. The question is whether American Catholics will be part of it.

David Gibson is a national reporter for Religion News Service.