The era before the Civil War, Walt Whitman argued, was the “before-times,” suggesting that everything after the Civil War was categorically different. In some way, all days before Oct. 7, 2023, were Israel’s “before-times”; the country now exists in the afterward.

Before Oct. 7, Israel was in the throes of one of the most divided moments in its history. Ideological battles raged, and there were deep debates about Zionism, democracy, equality, the divide between the religious and the secular, and the state of antisemitism worldwide. One of those conversations had to do with Religious Zionism, the movement whose latest iteration was formulated by Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook (1891-1982), son of Rav Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935), the first chief rabbi of Mandate Palestine and architect of a spiritual messianic Religious Zionism. Both Kooks began with the assumption—as did and do many other Zionists—that the land of Israel belonged to the Jews by dint of divine mandate, and that relinquishing any of it was blasphemous. Famously, even the secular Zionist and first Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion proclaimed “the Bible is our mandate” before the Peel Commission in 1937.

In November 2022, when Israelis elected the most right wing and Religious Zionist-dominated government in the country’s history, many wondered whether Religious Zionism had become the dominant political force in Israel, even for those who did not consider themselves part of the settler movement. The election of Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich and their party Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Strength) solidified the Religious Zionist influence in the ruling coalition. The Religious Zionist vision was now the dominant ideology of Israel.

The Religious Zionist argument is not fundamentally a “security” argument but a theological and messianic one. And yet, many secular Zionists—let us call it the neo-Revisionist center—were adopting a similar outlook under the guise of security. The remnants of any humanistic Zionism seemed to be fading quickly into the past. The notion of Greater Israel, once largely unique to the Religious Zionist perspective, had become normalized among many secular Israelis.

Seeing this happen, many on the diminished left, and center-left—religious and secular alike—argued that the Religious Zionists were kidnapping Zionism, (re)creating it in their own image and thus undermining the liberal tenets of a two-state future. The protest movement in 2023, when tens of thousands of Israelis took to the streets to protest judicial reforms that would weaken the largely liberal Israeli Supreme Court and give more power to the ruling coalition, illustrated that frustration in a profound way.

But those were the before times. In the wake of Oct. 7—and in the afterworld we find ourselves in now—the Greater Israel settler narrative came to seem not only viable but necessary, and its support extended far beyond those who identify with Religious Zionism. Religious Zionist rabbis were making all sorts of apocalyptic pronouncements, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu equated Hamas with the Biblical Amalek, calling for their eradication. We should recall that the commandment to eradicate Amalek in the Hebrew Bible is a call to genocide.

The secular and religious-left narrative of “justice and equality” seemed buried in the rubble of burned-out houses and fresh graves in the kibbutzim in the Gaza envelope. The Religious Zionist narrative now seemed to many the only course of action: survival through territorial expansion. “There is no choice” (ein bererah) no longer embodied the position of two states but the inevitability of Jewish Israeli domination, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict moved into the register of an “us or them” zero-sum game. That is precisely the attitude that the radical Religious Zionist camp finds most comfortable.

For a long time now, many who pay attention to this conflict and the shifting sands of Israeli society have argued that “religion,” here manifested in the ideology of Religious Zionism and ultra-Orthodoxy, was the problem. That is, the strident and chauvinistic ideology of what one might call Jewish supremacy was the product of a messianic religious ideology that was uncompromising in its treatment, or mistreatment, of the non-Jew in Israeli society, making true equality a non-starter. Maximalist in its claims of territory, such a worldview sees a two-state solution as not only risky politically, but also treasonous and even blasphemous.

In opposition to this deadlock is the thought of Rabbi Menachem Froman (1945-2013), who claimed that it is actually secular Zionism that is the problem, and religion—even one that was deeply rooted in the ancestral land of Israel—offered new ways to create conditions of coexistence with Palestinians, who he acknowledged also had rights to the land. Today, in this low point in the history of the land, Froman’s thought offers a potential but also radical path forward for Israelis and Palestinians alike.

Froman was raised as a Zionist, but not a religious one, and became religious as a teenager, becoming an early student of Zvi Yehuda Kook. He was a paratrooper during the Six Day War in 1967 and took part in the battle that resulted in the capture of the Western Wall from Jordanian rule. In 1974, he became one of the founding members of Gush Emunim (The Bloc of the Faithful), which served as the germ cell of messianic religious Zionism.

Froman distinguished himself from most of his compatriots in his belief that Palestinians had a legitimate claim to the land—that Palestine is and should be their home—and that it was secularism, and not religion, that actually stood in the way of peaceful coexistence. On the question of a Palestinian state—something most Religious Zionists oppose because it would require relinquishing territory now controlled by Jews, which some claim is prohibited by Jewish law and others say would reverse the messianic trajectory of Zionism—Froman made an audacious claim worth examining. He said that he would be willing to accept a Palestinian state as part of a resolution to the conflict and would be willing to be a citizen of Palestine, if he could remain in his home in Tekoa now in the West Bank, or what settlers call Judea.

Setting aside the impracticality of such an assertion (what is not impractical in today’s conflict?), Froman’s willingness to accept a Palestinian state struck at the very heart of the Religious Zionist project of Froman’s teacher, Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook. One of the most important additions Zvi Yehuda Kook made to his father’s teachings was the notion that it was not only the land that was holy (this was a central teaching of his father) but that the state itself was holy. The fusion of land and state became a central tenet that made territorial maximalism, or Greater Israel ideology, operational. By severing the state from land—claiming he would become a citizen of Palestine if he could remain on the land—essentially undermines the Religious Zionism of Zvi Yehuda Kook and, in some ways, returns Religious Zionism to the thought of Abraham Isaac Kook.

Today, in this low point in the history of the land, Froman’s thought offers a potential but also radical path forward for Israelis and Palestinians alike.

Abraham Isaac Kook died in 1935, thirteen years before the state was established, and thus never had to address this issue. But Froman’s assertion that he would happily live in a Palestinian state challenges the maximalist territorial claims of Religious Zionism while maintaining the sanctity of the land as independent of the state. The basis of that position is founded on the religious idea of the intimate relationship between the Jews—a sanctity that had been transferred into the political (and Froman might say secular) register of statehood. This is not to say that he opposed the state, but rather that he saw the sanctity of the state as a potential impediment to resolving the conflict that he believed could be resolved through religious means.

Although Froman was the product of the Religious Zionist movement that has come to dominate Israeli society, he questioned the very premises of Religious Zionism, and actively resisted the forms it took. Many think that the state and its political apparatus has become more “religious” through the influence of religious parties and religious ideology. As I read Froman, he sees it in reverse. That is, the empowerment of the religious parties and their fusion with the politics of the secular state actually make religion more secular and not the other way around. This insight makes his thought more urgent than ever.

Froman defined himself as a “primitive Jew.” He viewed his relationship to the land as one of autochthony—that is, a belief in a people that essentially emerges from its land. This is more than the land of Israel being the promised land of the Jews. It is as if his very flesh and bones rose from the rocky soil of Judea. He immersed himself in Kabbalah and Hasidism and yet was able to sweep away its xenophobia and chauvinism, as if clearing cobwebs from a beautiful piece of ancient furniture. He read Kabbalah “against the grain” (as Walter Benjamin put it), deconstructing its binaries into a dialectical fusion that the texts often hinted at but rarely executed.

More than that, Froman used these Kabbalistic texts to promote a social vision—a politics of repair (tikkun), founded on the shared ethos of landedness (nakhtut) and mutual respect for the primal desires of religion (Judaism and Islam).

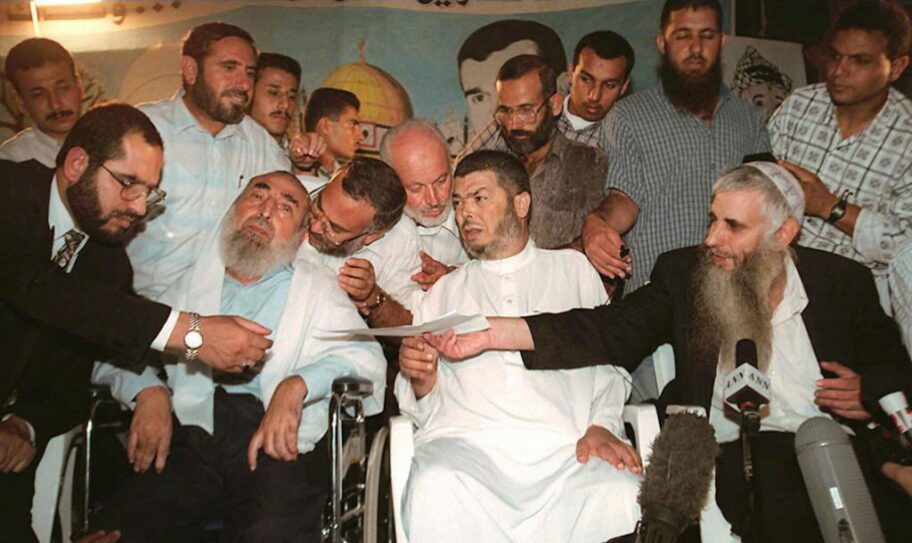

It is this sentiment that brought Froman to do what was unthinkable in the religious and secular sectors: meeting with the leader of Hamas, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, and meeting with members of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Indeed, Froman met with anyone who was willing to talk to him. He preferred meeting with religious Islamic—even Islamist—figures, because he believed they shared his fundamental beliefs and a shared commitment to the land. Politics, for Froman, was not endemic to the spiritual mindset but rather a secular deviation that created irreconcilable barriers to peace without one side dominating the other. But for him, a mutual belief in the land and the world as belonging solely to God enabled both sides to view themselves under the only true sovereign. Obsession with state sovereignty was a secular ideal, not a religious one—an idea he drew from Martin Buber’s reading of the Hebrew prophets. Buber argued that Israel’s desire for a king in the Book of Samuel (“give us a king that we may be like all the nations” I Samuel 8:20)—was the true beginning of Jewish secularism.

Froman’s political activism was intended to correct two philosophical errors that he thought dominated contemporary Israeli politics. First, secular Israelis were beholden to the false idea that the secular held the exclusive license of morality. Secular Zionism was founded on principles of humanism that emerged from the Enlightenment—a humanism that was not beholden to a belief in God. Perhaps this can be captured best in something Golda Meir allegedly said to the philosopher Hannah Arendt, that Arendt quoted in a letter to Gershom Scholem in July 1963: “As a socialist I don’t believe in God, I believe in the Jewish people.” Froman believed that severing belief in God from humanity was a recipe for disaster. Here in some ways he aligns himself with the thesis in Theodore Adorno and Max Hokheimer’s The Dialectics of the Enlightenment—that it was the Enlightenment itself that gave birth to fascism. Religion for Froman could indeed produce a dangerous fundamentalism, but it also contained humility, and a limit to human power, that could give birth to a true humanism.

The second problem that preoccupied Froman was his view that the religious were focused on the transcendent world at the expense of the material world. Froman argued that the secular horizontal axis of morality—the idea that human responsibility rests solely on a human-human encounter—can also be viewed vertically as part of a human-divine encounter. He believed that politics infused with the belief in God as the sole sovereign could enable human-human encounters to evolve beyond the desire for power. The vertical axis of religious devotion, meanwhile, could also be viewed horizontally, rooted in the deep soil of the land. The land, in Froman’s thought, plays a crucial role, as it represents, for both Jews and Muslims, the rootedness in the material that is also infused with the spiritual. And it is where spirit and land meet, according to Froman, that the religious Arab and the religious Jew can find—quite literally—common ground.

Froman’s notion of land-based “spirituality” is not exclusive to Jews, but includes others (in this case, Muslims) whose claim to the land of their ancestors is a legitimate spiritual, and thus also political, claim. It is also worth noting that Froman was an anti-diasporist Jew—he simply could not fathom Judaism severed from its land-based practice. This is the basis of self-identifying as a “primitive Jew.” In Froman’s thought, issues arise when religion serves politics instead of politics growing organically from the spiritual connection to the land. The problem of Religious Zionism, for Froman, is that in its entry into politics, religion had been subjugated to a secular paradigm, forced to serve the secular project of power.

Religion for Froman could indeed produce a dangerous fundamentalism, but it also contained humility and the limits of human power that could give birth to a true humanism.

In the wake of Oct. 7, I do not think it audacious to claim that we need to rethink everything: religion, land, Judaism, and Zionism. The old ways of thinking have either become obsolete or, alternatively, too frightening to imagine. This is how Whitman saw America after the Civil War. The all-too-common—and dangerous—binary of “friend and enemy” has taken hold after Oct. 7, and such a binary rarely if ever yields positive results. We see this in Israel, where we have come to the point that after accusations of Israel Defense Forces soldiers sodomizing a Palestinian prisoner in Sde Teiman in August 2024 there are Israeli parliamentarians who argue that sodomizing a prisoner should not be considered an actionable offense. For Froman, the eradication of evil comes not through annihilation but transformation. To destroy evil is to bring out the good within it. Engaging with the enemy has the potential to bring out the inherent, yet concealed, sanctity in their position, as well as evoke the spirit of generosity in our own position that has too often been enveloped in hatred and resentment.

From a secular perspective, this might sound like pure insanity. What would it mean to engage with someone who wants to kill you? But Froman tried to interrogate the true motivations of the opposition. The Palestinians too, he would argue, are God’s children. They too love their families and want them to flourish. They too are in pain. And they too have a deep connection to the land, just as he did.

To be sure, we cannot know how Froman would have reacted to Oct. 7. But given actions he took in his life, including meeting with Hamas and PLO spiritual leaders in prayer, one can imagine that his unorthodox vision of peace through spiritual activism would have withstood this atrocity and its aftermath. Many will find Froman’s program naïve and impractical, especially in these highly divisive times. His claim that the political right may have been able to lead the way to peace may sound dissonant. And Religious Zionists have certainly taken a very different path. It is true, Froman’s program requires a generosity of spirit that is hard to fathom in the anguish of this moment. Yet perhaps such a voice is necessary precisely when it seems irrelevant; perhaps Froman speaks to us when we seem least likely to listen.