The family, declared the highest leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1995, is ordained by God. “Marriage between man and woman is essential to His eternal plan.” The Proclamation on the Family functions as quasi-scripture for Latter-day Saints, but it has not settled anything. Since 1995, the church has become embroiled in high-profile and ultimately unsuccessful political campaigns against the legalization of same-sex marriage. Church leaders instituted and then quickly repealed a ban on the baptism of children of same-sex couples, and a sizeable percentage of young church members—15 percent or so—identify as something other than strictly heterosexual. Modern-day prophets are struggling in their attempt to navigate contemporary debates over sexuality and gender identity.

In Queering Kinship in the Mormon Cosmos (University of North Carolina Press, 2024), Taylor G. Petrey uses the past to look forward. Petrey—himself a Latter-day Saint, to use the language now preferred by those once called Mormons—suggests that the “hierarchy of heterosexual love over other human bonding” is a rather “strange” and recent development within this tradition. Early Mormonism, by contrast, was about kinship at least as much as it was about family. That’s correct, but the ambitions of Joseph Smith—the church’s founding prophet—were even broader and bolder.

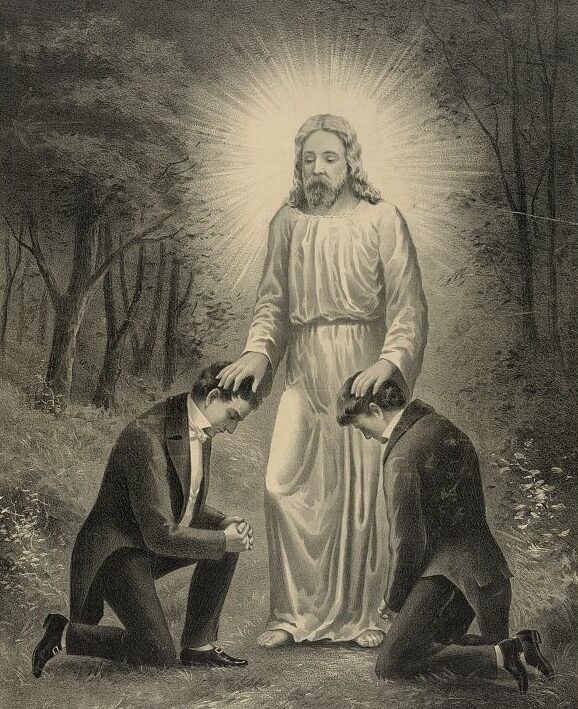

For Smith, Mormonism’s founding prophet, the model for human kinship was God. God wasn’t a three-in-one, immaterial, unchanging, apathetic deity, but an exalted Father in relationships of love and unity with a material Son and a non-corporeal Holy Spirit. There is a lot to unpack here. For example, are the members of the Godhead male? Petrey points to far more complicated language and imagery within both Mormonism and Christianity more broadly, but he also notes that those who insist on the maleness of the Father, Son, and Spirit produce “an acutely homoerotic scene of divine love.” The point is that a queer reading of “these supposedly stable symbols of hetero-masculinity reveal[s] a wonderfully fluid and ambiguous resource for an alternative kinship system to heteropatriarchy.” Humans with all sorts of sexualities, bodies, and identities could find an invitation to kinship within this theological vision.

And there’s more. Smith’s followers articulated the idea of a Heavenly Mother alongside God the Father. Church leaders have eschewed fleshing out her cosmic role. They underscore her importance but say relatively little about her. The church has excommunicated a number of theologians and activists who have carved out a greater space for Heavenly Mother in Mormon piety, whereas other Latter-day Saint women depict Heavenly Mother as an archetype of essentialist womanhood.

But Joseph Smith is more famous for what he did than what he espoused. The Mormon prophet was sealed in marriage to thirty or so women. He had sex with a good number of his wives. What should we make of this starting point? Did Joseph Smith introduce plural marriage in order to satisfy his sex drive? Or did he marry women to live out a theological principle? The historian Richard Bushman observed that Smith “did not lust for women so much as he lusted for kin.” Other scholars have rejected Bushman’s assertion, treating it as perhaps the wishful thinking of a scholar beholden to his faith.

Petrey stakes out not a middle ground but something beyond this binary choice. “The eroticism that runs through Joseph Smith,” Petrey suggests, “isn’t in contrast to his search for kin but is a manifestation of it.” There’s no reason to think that sexual desire didn’t play a role in Smith’s many marriages, but Smith lusted for something else as well. In his lust for kinship, Smith fashioned rituals that created or reaffirmed deep relational bonds among a wide variety of people.

The Gospel of John teaches that all who receive Jesus Christ “become sons of God … born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh.” God adopts Christians as spiritual children, and they become like Christ, full of divine glory. Early Latter-day Saints didn’t just seal men and women together in marriage, or children to their biological parents. Instead, shortly after Smith’s death, Mormon leaders began sealing couples to non-biological parents, customarily to church hierarchs and their wives, grafting them into lineages of priesthood that would bring about their exaltation. (Petrey errs by suggesting that Smith himself introduced the practice). The overarching concept here is sealing. Latter-day Saints sealed husbands to wives, children to parents, and the living to the dead through proxy baptisms and other proxy sealings. Sealings created a chain of kinships that connected the human family back to their heavenly parents. Petrey concludes that both adoption and polygamy “were transgressive of the [Victorian] family” insofar as they expanded its borders.

Petrey’s point isn’t that his tradition was ever unstintingly transgressive. Even Smith’s most radical ideas took place in the context of racism and patriarchy. Polygamy was “the patriarchal order of marriage,” after all, and rituals of adoption gave top-ranking church leaders their own familial fiefdoms. Petrey isn’t under any illusion that the Mormon past provides today’s Latter-day Saints with a ready-to-use set of beliefs and practices for a more progressive future. Instead, he leans into Judith Butler’s concept of resignification, to find ways—in his words—of “reinterpreting and reusing existing language, symbols, and cultural norms in order to challenge and subvert their traditional meanings.” The tradition provides resources for ongoing critique and protest.

Petrey acknowledges that, for him, Queering the Mormon Cosmos isn’t “just an academic exercise.” It is a “passionate quest,” a testimony to his own “lust for kinship that acknowledges and embraces the complexity of human relationships in all their varied forms.”

The problem with Petrey’s vision is that Latter-day Saint leaders, not known for their fondness of critique and protest, don’t share it. Church leaders avoid the harsh anti-gay rhetoric of their predecessors, and they’ve made their peace with the civic legalization of same-sex marriage. But they aren’t backing away from what Petrey would label “heteropatriarchal normativity,” in doctrine and rituals that reify heterosexual marriage. The church’s General Handbook warns that those who live in a “same-sex marriage” could be excommunicated. The church also recently introduced more detailed restrictions on the participation of transgender children and adults. For instance, adults who “pursue surgical, medical, or social transition away from their biological sex at birth” may not serve in “gender-specific roles” in the church or “work with children or youth.” Children, moreover, must attend “gender-specific meetings and activities that align with their biological sex at birth.” The church couples these warnings and restrictions with an injunction to “treat individuals and their families with love and respect while teaching gospel truth”—to, in effect, love sinners while hating, or at least lamenting, their sins. Whether love and respect are shown often depends on the attitudes and practices of local church leaders and members.

The problem with Petrey’s vision is that Latter-day Saint leaders, not known for their fondness of critique and protest, don’t share it.

No approach or basket of policies will make these issues go away or provide uncostly solutions. A growing number of young Latter-day Saints identify as something other than heterosexual. Much higher percentages of church members across all ages believe that same-sex marriage and relationships should be accepted. A significant number of individuals who leave the church identify as LGBT+. If the church tacked in a progressive direction, perhaps more of its queer members would remain faithful. But perhaps not. Progressive Protestant denominations have an abysmal track record at passing on faith and membership to rising generations, and large numbers of more conservative Latter-day Saints would rebel if the church abandoned long-standing doctrines and practices. Discussions of these issues typically focus solely on the church’s American members, but most Latter-day Saints live in other countries. Progressive decisions reached in Salt Lake City would not play well in São Paulo.

Still, Petrey is correct to suggest that Latter-day Saints could find resources for the present in their history. That is, after all, a very traditional Mormon notion. At several points in their history, church leaders have undertaken dramatic shifts in policy, despite very real dangers of heightened disunity. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the church defended plural marriage as a sacred, essential principle, then abandoned it. It was a costly about-face, one that led to polygamous splinter movements. By contrast, the 1978 revelation that extended the priesthood and sacred ordinances to Black members was greeted with widespread acclaim, but there was substantial if less visible opposition to this decision as well. The contemporary church has a reputation for glacial change, and these past examples showcase its ability to stay the course in the face of intense outside pressure, but Latter-day Saint principles of prophetic leadership and ongoing revelation make sweeping and sudden change conceivable.

And sweeping, sudden changes were always possible for early Mormons. Joseph Smith was open to new directions that startled and shocked his followers: Move to Ohio. Move to Missouri. Build cities. Build temples. Establish a bank. Be baptized on behalf of the dead. Go back to first principles about the nature of God and human beings. Marry for eternity. Reorganize the shape of those eternal families on earth.

In the long run, this audacity wasn’t sustainable. In many Protestant churches, you can’t change a word in a hymn or the color of the carpet without risking a schism. It wouldn’t be prudent or even possible for aging Latter-day Saint hierarchs to recapture Smith’s dynamism. And whether they chose to move toward the full inclusion of LGBT+ individuals or chose to resolutely defend “traditional” sexual morality, would the issues ever be settled, as prior debates about polygamy or race and the priesthood were? Cultural mores about sexuality and gender keep shifting, and with those shifts come fresh expectations that churches conform to or resist new developments. Hence Petrey’s call for ongoing critique and protest rather than a list of specific reforms. But for many Latter-day Saints, as for many other Christians, ongoing critique and protest would surely prove more exhausting than exhilarating. Endless, roiling debate has not helped the Methodists or Episcopalians, not in unity nor in numbers.

A “lust for kinship” wasn’t the only desire at the center of Joseph Smith’s activities. Another signal contribution was Smith’s vision of Zion, one of many terms from the Bible that he reinterpreted and reused. In what amounted to an expansion of the Book of Genesis, Smith had Enoch found a city. “The Lord,” the text records, “called his people Zion because they were of one heart and of one mind.” Smith wanted his people to emulate Enoch’s. They would establish a unity that had eluded American Protestants. Smith’s followers practiced what he preached, creating communities in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois.

Throughout their history, Latter-day Saints have been builders, “doers of the word, and not hearers only.” At times, new doctrines and new directions have divided them. It is, after all, very difficult for any group of people to remain “of one heart and of one mind” for very long, especially when it comes to the thorny social and political issues of the early twenty-first century. None of us are good enough prophets to know what the dominant ideas about human sexuality or gender identity will be in twenty or fifty years. As in many other Christian denominations, Zion-like unity on such subjects seems next to impossible. Early Mormonism, though, was never about reaching agreement on matters of theology or doctrine. It was about people from a wide variety of backgrounds accepting the prophetic leadership of Christ’s one true church and choosing to work together to build Zion. For Latter-day Saints, can the old be new again?