Since the murder of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson, the alleged killer, Luigi Mangione, has been either venerated as a folk hero or disparaged as a left-wing crank, a symptom of the rising violence infecting the American political system. But such polarized responses misread Thompson’s death as a simple case of heroic populism or left-wing blood thirst. Mangione, a computer scientist from a wealthy family, and a man with no history of politicized bloodthirst, fits neither stereotype. The reactions to Mangione tell us very little about Mangione himself. Rather, our reactions to his alleged act tell us something about us, all of us. Our reactions are worth inspecting as a genre of American political discourse—how it constructs its story lines.

Every event, every political struggle, is turned into a melodrama, and divided into the forces of light and darkness, heroes and villains—or, to use the terminology of pro-wrestling, faces and heels. To miss our culture’s “will to melodrama” is to be swallowed up by the endless back-and-forth of online politics. To be aware of it is to make possible an analysis that does not follow a conventional script—an analysis that truly engages with the long history of American political and economic assassinations.

Melodrama is the narrative engine that drives American entertainment and politics. Almost everything we watch, from gangster movies to superhero franchises, from westerns to thrillers, pretty much all “Peak TV,” follows melodrama’s basic formula of dark versus light. The melodrama’s cast of characters includes victims, perpetrators, saviors, rebels, and avengers. Among these, the most important is the “ordinary” person forced into an extraordinary situation. Think: Walter White (Breaking Bad), Piper Chapman (Orange is New Black), Marty Byrde (Ozark), or Angela Abar (Watchmen). All begin their series as typical middle-class mothers, fathers, or fiancés and end up as drug kingpins, superheroes, and criminals.

Every event, every political struggle, is turned into a melodrama, and divided into the forces of light and darkness, heroes and villains.

This melodramatic schema is not new to American history. Over a century ago, the idea of a well-educated man or woman being motivated by idealism to commit murder would not have seemed so strange, though it was certainly cause for great alarm. From 1880 to 1914, during what Christopher Andrew calls the “Golden Age of Assassinations,” anarchists and communists in America and Europe targeted countless business leaders, politicians, and royal figures with the idealistic intention of fomenting revolution. Then, as now, a small sliver of society controlled the majority of wealth and political power. Then, as now, ordinary working people struggled to adapt to the pace of industrial and technological change. Then, as now, a few of those people—recent immigrants, some with names resembling Mangione’s—took matters into their own hands.

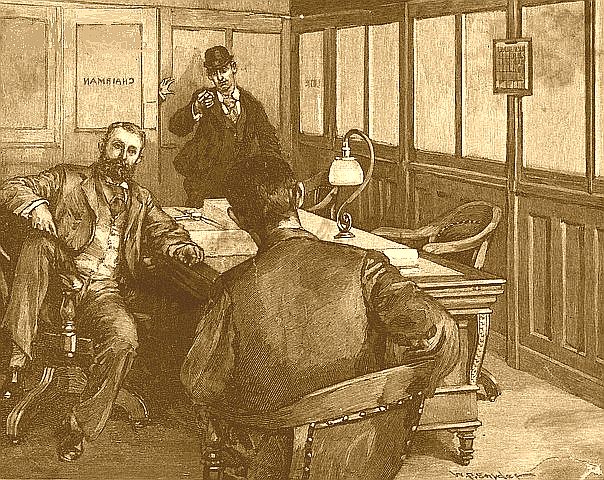

In 1892, for instance, the anarchist Alexander Berkman attempted to assassinate the industrial manager Henry Clay Frick, following the brutal suppression of a strike at a Carnegie steel plant. Some of the details of Berkman’s story resemble Mangione’s. Like Mangione, he planned patiently and meticulously, studying the places Frick lived, worked, and frequented. Also like Mangione, prior to the attack, he checked into a nearby hotel under a false name—Rakhmetov, the idealistic hero of Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s 1863 novel What Is to Be Done? Unlike Mangione, however, Berkman missed his mark. After bursting into Frick’s Pittsburgh office, he managed to fire off two shots before a carpenter, having overhead the struggle, stormed the office and hit Berkman upside the head with a hammer.

Like his comrades, Berkman was motivated by a notion of “propaganda by the deed,” a fundamental tenet of anarchist philosophy. Though far from espousing anarchist views, Mangione’s manifesto seems inspired by a similar logic. “Many have illuminated the corruption and greed,” he wrote, but “the problems simply remain,” making him “the first to face it with such brutal honesty.” For Mangione, actions make up for the failure of words. In the media, on the internet, those actions are translated back into words according to a melodramatic script that provides moral clarity—or, in scholar Peter Brook’s term, “moral legibility.” In some versions, Mangione is the villain, and in others the hero. But the fundamental outline remains.

For Brooks, melodrama’s capacity to paint a stark, black-and-white picture fills a gap in moral authority that appeared following decline of the Catholic church and the triumph of Enlightenment secularism during the French Revolution. In the American melodrama, this fight between good and evil is personalized to meet the demands of psychological realism. The motivations that justify a character’s actions, whether they’re a gravity-defying superhero or an inveterate couch potato, should accord with those of an “ordinary” (read: middle-class) person. At the same time, those characters, whether fictional or real—whether Tony Soprano or Luigi Mangione—stand in for ideas larger than themselves. The battle to define them and their motivations is a battle for the soul of the nation. Understanding this fundamental fact explains why so many have taken up their pens in writing the next episode of America’s melodramatic script.