My twenty-fifth birthday celebration was typical for a young New Yorker: black going-out tops, alcohol, songs from college on loop, and friends, new and old, filtering in and out of my walk-up apartment. Around midnight, we hit the second location: a club in one of the seedier parts of the Lower East Side, complete with overpriced drinks and a late-night Uber home.

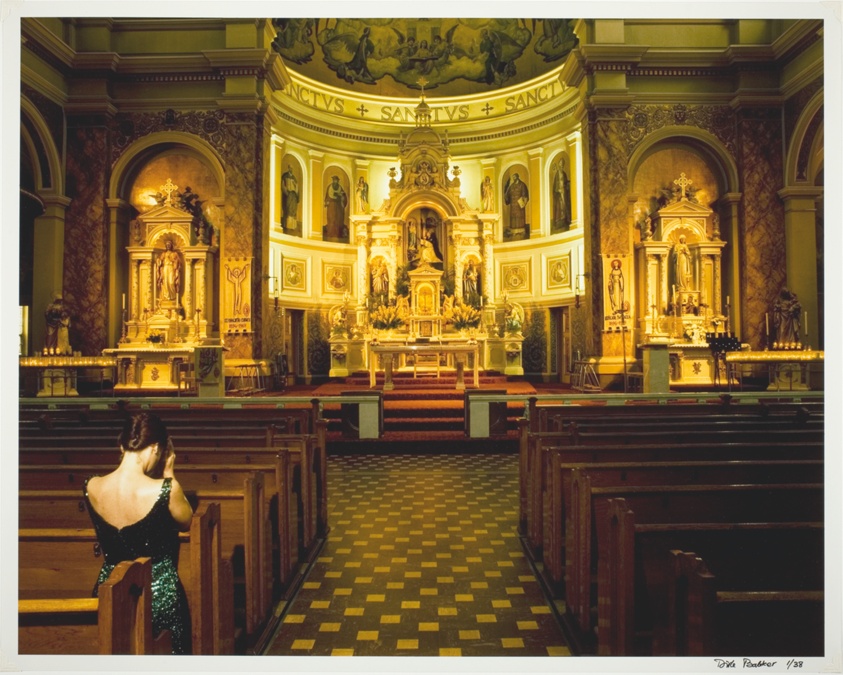

Except we made a stop before home: St. Vincent Ferrer Catholic Church, on the Upper East Side. Around 3:30 a.m., we tumbled out of the Uber and through the side door of the quiet church, where, to our surprise, a few other people were gathered. In silence, we knelt, looking at what was displayed at the altar: a skull reputed to be that of St. Thomas Aquinas, part of the living man in the 1200s, now bare before us, during an all-night vigil on a cold December night eight hundred years later.

You might think that post-club is an odd time to venerate a Catholic relic, to which I say: I was seeking the empty headspace of the very tired (and half-deaf), so I could better feel the presence of God. After some time, we got up, genuflected, and went home.

That wasn’t the only time I was at church that weekend. About seventeen hours earlier, two friends and I had come to participate in a church cleanup session prior to party prep. Nine hours after that late-night prayer, I was back in church once more, sleepy but present, for noon Mass. And it’s not just weekends, either: sometimes I’ll come for weekday Mass when I feel I need it, and other times, I’ll just sit in the back of the church, glad to mull things over in God’s presence. And even beyond: I attend a weekly Bible study with close church friends. All told, it’s an odd day if I’m not doing something related to the church.

You might think that post-club is an odd time to venerate a Catholic relic, to which I say: I was seeking the empty headspace of the very tired so I could better feel the presence of God.

According to 2023 Gallup data, 68 percent of Americans identify as Christian. But according to that same data, fewer than half of those Americans attend church weekly and belong to formal houses of worship. There are, of course, many ways to be Christian. But the numbers imply that most self-professed Christians do not gather with their fellows to celebrate God. And that’s not good.

“Going to church”—attending services, yes, but also communing with one’s church community and devoting time to its development—should be a major component of Christian life. The most obvious reason why is purely doctrinal, with the third commandment telling believers to “keep holy the Sabbath.” But attending church services and participating in the larger church community also has enormous potential to draw a person closer to God, and in an age in which time and attention are at a premium, actively choosing to spend time in the presence of God, with others as companions, is needed to keep one’s faith from falling by the wayside.

It’s an odd day if I’m not doing something related to the church.

Church communities can be messy. Where people gather, drama can follow. (I unfortunately am still very interested when I find out a church-affiliated couple has broken up.) But church, and the community that comes with it, can also keep you honest. The time I spend at church cleaning days or services might otherwise be spent wasting time on my phone, and my Bible study group means that I devote multiple regular hours a week (and many group chat conversations) to thinking about my faith. The few times that we cancelled Bible study for the week, I could already feel myself slipping, maybe not in behavior, but in thought—free of the task of reading the book of Job and having to answer questions about it, I thought about God and my relationship to him less. Our next Bible session made me realize how much I needed the weekly study.

You can read the Bible and think about God on your own, of course. But one of the most plainly obvious facts of the Bible is that Jesus did not operate in a vacuum. Even when he wasn’t actively ministering to crowds of the poor, sick, or despairing, he was surrounded by twelve apostles. And Jesus’ major miracles involved other people, often hordes of them: the loaves and the fishes was a miracle of hospitality to thousands, the water into wine happened at a wedding, and even the raising of Lazarus happened in a household full of the bereaved.

I know that I’m lucky. Not everyone has a thriving community in which to develop her or his faith. I know from experience: even growing up in a largely Catholic neighborhood, my parish didn’t offer much. Other churches, while busy, don’t focus on their young adult populations, and for a young person with a lot of major life decisions to make, having a cadre of Catholic twentysomethings nearby means a lot. On the other hand, St. Vincent’s and other churches, especially in cities (like Immaculate Conception in D.C. and St. Patrick’s in Philadelphia, according to friends) have thriving young-adult communities that take little effort to join, and activities ranging from theological study groups to weekend retreats. If I move, the presence of such a church community will be a major factor in whatever new home I choose. (Of course, if you find that you lack such a community, you can always try to help develop one.)

I don’t only do church things. I have a day job, I go to the gym, and I have many friends who aren’t Catholic. But my church fills enough of my life that I can confidently say it’s one of those villages whose demise everyone seems to be lamenting. Indeed, in September The Atlantic published an essay claiming that, nowadays, “[y]ou can’t just show up on a Sunday and find a few hundred of your friends in the same building.” But can’t you?