In 1993, Giorgia Meloni—now Italy’s prime minister and leader of the far-right Brothers of Italy—attended a revival of Camp Hobbit. The original Camp Hobbit was staged in 1977 by the youth wing of the Italian neo-fascist party, the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI). Dubbed the “Woodstock of Italy’s far right,” these outdoor festivals repurposed imagery from the writing of J. R. R. Tolkien in an effort to draw young people to right-wing politics. When she attended the revival, Meloni was sixteen, a young activist with the Fronte della Gioventú (FdG), the youth wing of the MSI. At Hobbit ’93, the young militant sang with the radical folk-band La Compagnia dell’Anello (The Fellowship of the Ring).

Tolkien was foundational to her personality and political identity. She once dressed as Samwise Gamgee, her favorite character from The Lord of the Rings. Samwise wasn’t flashy like Gandalf and Aragorn but humbly devoted to a larger cause. As she wrote in her memoir, “He was only a hobbit, a gardener, but without him Frodo would never have carried out his mission. As Tolkien wrote, ‘It is the small hands that change the world.’”

“I don’t consider ‘The Lord of the Rings’ fantasy,” she told The New York Times.

The Lord of the Rings has fans across the political spectrum, but as the Tolkien scholar Robert T. Tally Jr. has observed, there is “a vast and possibly growing international cohort of Tolkien fanatics who openly embrace white supremacist, racist, anti-immigrant, neo-Nazi, and otherwise right-wing ideologies, many of whom take The Lord of the Rings as something like holy scripture.” They turn to Tolkien, he argues, in pursuit of “an order that resists change,” but in doing so they badly misread him.

Many conservative Tolkien fans want to reverse aspects of modernity. But as numerous commentators have noted, a group of techno-reactionary entrepreneurs—many aligned with Silicon Valley’s MAGA wing—have grander ambitions. They’ve drawn inspiration from Tolkien’s legendarium to reimagine the relationship between technology and politics, celebrating power while sidestepping democratic accountability.

Like Meloni, they don’t treat The Lord of the Rings as a mere fantasy, but they are not primarily driven by nostalgia. The Silicon Valley right doesn’t just borrow from Tolkien; they reforge his moral vision into a weapon for a new age. They envision a new kind of privatized national-security state, merging the oligarchic power of Silicon Valley, the deep pockets of venture capital and private equity, and the lethal might of the U.S. military—a military-industrial complex with Tolkienesque characteristics.

The leader of this dark fellowship is Peter Thiel.

Growing up in the Bay Area, Thiel was a devoted fan of science fiction and fantasy—and especially Tolkien. According to the journalist Max Chafkin, Thiel boasted that he had memorized the entire The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Thiel has named several of his companies after Tolkien’s mythology. Most prominently, he named the software and data analytics company he co-founded Palantir Technologies, after the palantiri, seeing stones from Tolkien’s world that let users observe distant events and communicate telepathically.

The palantiri are perilous tools, prone to misuse and known to amplify users’ weaknesses. The Dark Lord exploits them to manipulate Saruman and Denethor, Steward of Gondor. Palantir adopted the motto, “Save the Shire.” It has won contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, the CIA, and other government agencies. Accusations of hubris against the company have become almost routine. As one activist slogan put it, “You can’t save the Shire if you work with Sauron.”

Thiel’s Valar Ventures takes its name from the Valar, demiurgic figures in Tolkien’s cosmos. Mithril Capital Management is named after a rare and prized metal. Rivendell One LLC is named for the home of Elrond; Lembas LLC for a nourishing elven bread. The naming of these enterprises suggests an identification between disruptive technologists and Tolkien’s elves and Valar. Thiel casts himself as the maker of powerful—and treacherous—technologies, aloof from the realm of mortal men.

The Silicon Valley right doesn’t just borrow from Tolkien; they have reforged his moral vision into a weapon for a new age. They envision a new kind of privatized national-security state, merging the oligarchic power of Silicon Valley, the deep pockets of private equity, and the lethal might of the U.S. military—a military-industrial complex with Tolkienesque characteristics.

Then there’s Palmer Luckey, an entrepreneur with a name and personal style redolent of a minor villain in a Thomas Pynchon novel. In a Tablet profile, Jeremy Stern describes Luckey as “a vengeance-seeking icon of counterelite Americana.” Stern means this as praise. He depicts Luckey as a defiant innovator with a penchant for Hawaiian shirts and flip-flops. Luckey founded Oculus VR, which he sold to Facebook (now Meta) in 2014 for $2 billion. Luckey was fired in 2017 after donating $10,000 to Nimble America, a pro-Donald Trump group known for circulating anti–Hillary Clinton memes. Internal backlash at Facebook reportedly contributed to his firing.

After leaving, Luckey founded Anduril Industries, a “defense product company” named for Aragorn’s sword, Andúril—originally Narsil, the Flame of the West, the Sword reforged, which signifies Aragorn’s claim as heir to Isildur. The venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund were early backers.

An essay on Anduril’s website describes its mission as “rebuild[ing] the arsenal of democracy [to] make that future safe, prosperous, and free.” The firm has won contracts with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Air Force, and other federal agencies. Luckey draws from Tolkien a symbol of legitimate power, envisioning the tech CEO less as an elf lord than as the king returned.

Varda Space Industries is more ambitious still, dreaming of building factories in orbit that use microgravity to manufacture high-purity pharmaceuticals, precision fiber optics, and other goods hard to make on earth. Varda Elentári is a character in The Silmarillion. She is Queen of the Stars, the being who is responsible for making them. One of the founders, Delian Asparouhov, posted on X wearing a MAGA hat, writing: “Unfortunately in SF people think this symbol is closer to a swastika than what it represents, which is hope, for about half of America.”

The current vice president of the United States is similarly Tolkien-pilled. On a 2021 episode of the Grounded podcast, JD Vance named Tolkien as his favorite author. “I’m a big Lord of the Rings guy,” Vance explained, “and I think, not realizing it at the time, but a lot of my conservative worldview was influenced by Tolkien growing up.” Vance was a protégé of Thiel. Backed by his mentor, he named his venture capital fund Narya Capital, after the Ring of Fire, one of the Three Rings of Power created by the elves. Tolkien distinguishes the three Elven rings from the seven for dwarves and the nine for men: they remain free from Sauron’s corruption. It is Gandalf the Gray who finally comes to bear Narya. His ring inspires courage in others and counteracts despair.

One might imagine that Vance is more of a mainstream conservative than the rest of this Silicon Valley set. Isn’t he concerned with reviving traditional values, promoting natalism, and reindustrializing the American heartland? Perhaps, but then he is also a proponent of accelerating the trends in automation and AI that would make deindustrialization look minor by comparison. In remarks delivered at the Artificial Intelligence Action Summit in Paris, the vice president asserted, “The A.I. future is not going to be won by hand-wringing about safety.”

Perhaps then, Narya represents for Vance all the power associated with the One Ring—while evading the inconvenient fact that Tolkien intended The Lord of the Rings as a warning against the temptations of power. These men seem driven to ignore such warnings. Tolkien stokes formative fantasies of virtuous power—fantasies increasingly realized in the reality the rest of us inhabit. To his credit, Palmer Luckey admits as much—half in jest, half in alarm:

I’m quite concerned that I’m doing what I was programmed to do when I was 8 years old. If you like Yu-Gi-Oh! and the Power Rangers, can you really do anything except build virtual reality and tools of violence to enact your aims while feeling superior?

Good question.

With the rise of his right-wing fans, many seek to rescue Tolkien’s legacy from his Silicon Valley admirers. These defenders point out that the professor unequivocally opposed fascism and denounced antisemitism, suggesting also that he would reject conservative warmakers who invoke him. Moreover, Tolkien’s defenders argue, Middle-earth is not only an escapist fantasy, but a critique of industrial modernity. They note, too, that Tolkien rejected allegorical interpretations of his novel. In the 1966 foreword to the second edition, he wrote, “As for any inner meaning or ‘message,’ it has in the intention of the author none.” He would surely resist political appropriations of his stories.

Such defenses can verge on special pleading.

The Oxford don was a conservative—temperamentally, and arguably politically. The fantasy writer Michael Moorcock wrote, in his 1978 essay “Epic Pooh” and elsewhere, that Tolkien was a “crypto-fascist,” a reactionary proponent of an idealized past. “[C]hildren’s books,” Moorcock observed, “are often written by conservative adults anxious to maintain an unreal attitude to childhood.” Moorcock may go too far, but Tolkien does build his fiction atop a romantic longing for a mythological history, though he recognizes it cannot be reclaimed. Writing in his own defense, Tolkien resisted critics who “seem determined to represent [him] as a simple-minded adolescent.” He insisted: “Mine is not an ‘imaginary’ world, but an imaginary historical moment on ‘Middle-earth’—which is our habitation.”

Yet Tolkien was clearly wistful for what had been lost.

Born in 1892 in South Africa, Tolkien moved to England with his mother and brother in 1896 after the death of his father. He was educated at King Edward’s School in Birmingham and Exeter College at Oxford, where he studied classics before switching to English. A devoted Catholic, he was dismayed by the Church’s reforms in the mid-1960s. He disliked the vernacular liturgy and remained devoted to the mystery and tradition of the Latin Mass.

Tolkien served as a signals officer in the British Army during World War I, arriving at the Somme in June 1916. As a signals officer, he managed communications between his unit and higher command, often under artillery fire. The Somme was a living nightmare. Artillery vaporized the earth, blasting trees. The sound of shelling was ceaseless. The air reeked of corpses, stagnant water, and cordite. Rain poured down, drowning men and horses in mud-filled craters. Trenches collapsed and flooded. Men lived in filth. Over 141 days, more than 600,000 Allied soldiers were killed or wounded, including Tolkien’s close friend Robert Gilson. By November, Tolkien was evacuated to England with trench fever, a bacterial illness transmitted by lice.

While convalescing, Tolkien returned to the personal mythology he had begun years earlier, writing a foundational story of Middle-earth, “The Fall of Gondolin.” Tolkien’s experience of the Somme shaped his conception of the Dead Marshes and the Black Gate of Mordor. At the end of Return of the King, the Scouring of the Shire sees the hobbits’ pastoral homeland overrun by ruffians and the industrial scheming of Saruman, now disguised as Sharkey.

The fantasy writer Michael Moorcock wrote, in his 1978 essay “Epic Pooh” and elsewhere, that Tolkien was a “crypto-fascist,” a reactionary proponent of an idealized past.

Tolkien’s anti-industrial, pastoral worldview was joined by a suspicion of the state. In a 1943 letter to his son, he wrote: “My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs)—or to ‘unconstitutional’ Monarchy.” He distrusted the state and idealized small, self-governing communities. The Shire has a figurehead Mayor and largely idle Shirriffs. Bounders patrol the border, keeping watch for intruders and troublemakers.

Tolkien’s description of orcs has been criticized for relying on racist tropes. In one letter, Tolkien describes orcs as “squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes: in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-type.” The scholar Helen Young argues that Tolkien established the “habits of Whiteness” of modern fantasy. One might argue, as Tally notes, that the orcs of Middle-earth were made, not born. And “orcishness” served Tolkien as a metaphor of the negative traits of individuals of many races and nationalities. Yet the hobbits are suspicious of outsiders.

Tolkien’s ideal stateless society paradoxically makes room for kingly power—albeit of an “unconstitutional” type. He wrote: “Give me a king whose chief interest in life is stamps, railways, or race-horses; and who has the power to sack his Vizier (or whatever you care to call him) if he does not like the cut of his trousers.” We do not know if Aragorn was a stamp-collector, but his example is instructive.

Aragorn’s authority rests not only on his legitimate claim to Gondor’s throne, but also on the willing devotion of his people. This is democracy without elections. In this world, great men win loyalty, and loyalty bequeaths legitimacy. Just as Samwise faithfully serves Frodo, so the Shire embraces the protection of the Reunited Kingdom at the dawn of the Fourth Age. Aragorn, ruling as King Elessar, decrees the Shire a Free Land, granting it full autonomy and self-governance. A neat bargain.

So Tolkien was, at the same time, a genteel libertarian-populist and an advocate of unconstitutional monarchism, a paradoxical combination. One suspects that certain hobbits would enthusiastically join the MAGA coalition—especially those petty, greedy, status-hungry Sackville-Bagginses.

For leftist fans and scholars, the goal of their advocacy goes beyond defending the author from misinterpretation. Many leftist Tolkien readers don’t claim that Tolkien secretly held progressive opinions. Rather, they claim that The Lord of the Rings—and the fantasy tradition it inspired—can help us recognize certain truths about today’s political landscape. The real stakes lie in the politics of fantasy.

We might read progressive fantasy authors like Ursula K. Le Guin, Samuel R. Delany, China Miéville, or N. K. Jemisin. But it is just as important, as the Marxist scholar Fredric Jameson would advise, to read conservative texts against the grain. Reading dialectically, we can see that even the most manifestly conservative literature encodes utopian hopes that transcend the limits of the present. Jameson dismissed Tolkien, but Tally, a student of his, brings a fine dialectical eye to The Lord of the Rings.

Tally writes that “[f]antasy is fundamentally the literature of alterity, a means of empowering the imagination to think of the world differently.” Capitalism limits the imagination. The concept of the free market disciplines our wildest dreams. Scarcity, opportunity cost, Pareto efficiency, diminishing returns—these are the watchwords of a society determined to remind us of the limits of individual and collective agency. But Tolkien opens up a space for imagining a changed and possibly better world.

So fantasy is political, and it can be a powerful tool for examining and reimagining our ossified reality. Other scholars conduct similar dialectical readings. Ishay Landa sees The Lord of the Rings as torn between affirming and critiquing private property. He argues that the One Ring of Power embodies the contradictions of capital. Gerry Canavan emphasizes that Tolkien describes The Lord of the Rings as a translation of a historical document. Reading the novel as a straightforward tale of heroism misses its self-awareness: the events it recounts are mediated and contested even within the world of the story. All those long appendices really do matter.

On this view, the problem with Tolkien’s right-wing admirers is not exactly that they misread him. There is ample textual support for right-wing interpretations. Rather, the problem is that they selectively strip-mine Tolkien, ignoring the novel’s dialectical tensions and Utopian dreams. Novels mean more than just what they say.

I largely agree with Tolkien’s leftist interpreters.

Tolkien can teach us a lot about capital—and politics more broadly. But fantasy’s utopian power can cut in unexpected directions. Anti-capitalists aren’t the only ones who dream of escaping limits. Techno-reactionaries, too, dream of freedom—from the shackles of democracy, regulation, and bureaucracy. They envision seasteads, charter cities, and New Zealand bunkers. Tolkien helps them shape and legitimize that grim dream.

The neoreactionary writer Curtis Yarvin, for example, has drawn on Tolkien to frame his brand of monarchism. On Gray Mirror, his Substack newsletter, he likens elites to elves and ordinary Americans to hobbits. He casts himself as a “dark elf,” cynically allied with hobbits in opposition to the ruling order. Yarvin writes that the goal of the “Tolkien-pilled” dark elf is “to win the culture war”—without the help of hobbits. After all, what self-respecting dark elf would want to “smell like a hobbit”?

Yarvin influenced Thiel and Vance, and he may have informed Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). The goal of DOGE can sometimes seem less like reducing government waste than creating an unaccountable power center within the executive branch. As in Yarvin’s vision, counter-elites seek to rule America with ruthless technocratic efficiency. They claim to prize competence and rationality but must occasionally appease the hobbit plebes whose consent lends legitimacy to techno-monarchical rule. It remains to be seen which MAGA faction is stronger: the dark elves or the hobbits.

Nonetheless, techno-reactionaries have found, in The Lord of the Rings, a lexicon of power. In the hands of Thiel and his allies, Tolkien’s mythic past hardens into a post-capitalist regime of enclosed economic fiefdoms ruled by sovereign CEOs. Recent commentators on the left and the right have reached for “the feudal” as both model and metaphor for how major Silicon Valley firms are transforming capitalism.

Some—like the French economist Cédric Durand and the economist and former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis—prefer the term technofeudalism. They argue that companies like Alphabet, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta extract cloud rents rather than profits. Users provide unpaid labor—above all their data—which platform owners monetize. Silicon Valley has killed capitalism, on this account, replacing markets with cloud-based walled gardens. Rent displaces profit as the dominant form of extraction.

Jodi Dean applies the label neofeudalism to the wider landscape this data-extraction regime has created. While data-capture remains central for her, she focuses more on its political consequences. As state capacity is increasingly privatized, democratic publics lose sovereignty. A cadre of platform billionaires dominate economic and political life, accelerating inequality and exercising increasingly direct forms of rule.

Both accounts see oligarchy as hardening into fiefdoms unaccountable to democratic oversight. A nexus of finance capital, high-tech monopoly, and privatized state capacity has empowered wealthy individuals who now operate beyond the bounds of the state or the market, establishing quasi-personal relations of domination over users and subcontractors.

Is capitalism really becoming technofeudalism? In “Critique of Techno-Feudalism,” an essay for the New Left Review, Evgeny Morozov expresses skepticism. He thinks such claims mostly trade on “shock value in the proclamation to rouse the soporific public from its complacency.” Our moment, he argues, is bleak but still fundamentally capitalist in character.

What does seem persuasive, however, is that technofeudalism is a foundational fantasy of Silicon Valley’s MAGA wing. Books like Thiel’s Zero to One celebrate the figure of the monopolist. “Monopoly is the condition of every successful business,” he writes. Real visionaries build a moat around valuable property and establish market dominance. They don’t compete effectively; they effectively avoid competition, which is for losers.

Firms like Palantir aim to build the privatized digital infrastructure of an AI-empowered national security state. They incarnate a new venture capital–and private equity–backed funding model for defense tech companies. Fuelled by initially small investments, they seek government pilot contracts to establish their credibility, then raise larger sums on the foundation of that credibility. Seven- or eight-figure seed rounds become multi-million-dollar national-security contracts become nine- and ten-figure rounds, leading to billion-dollar valuations and finally initial public offerings.

It’s a lethal flywheel that fuses defense companies, venture capital, and privatized government.

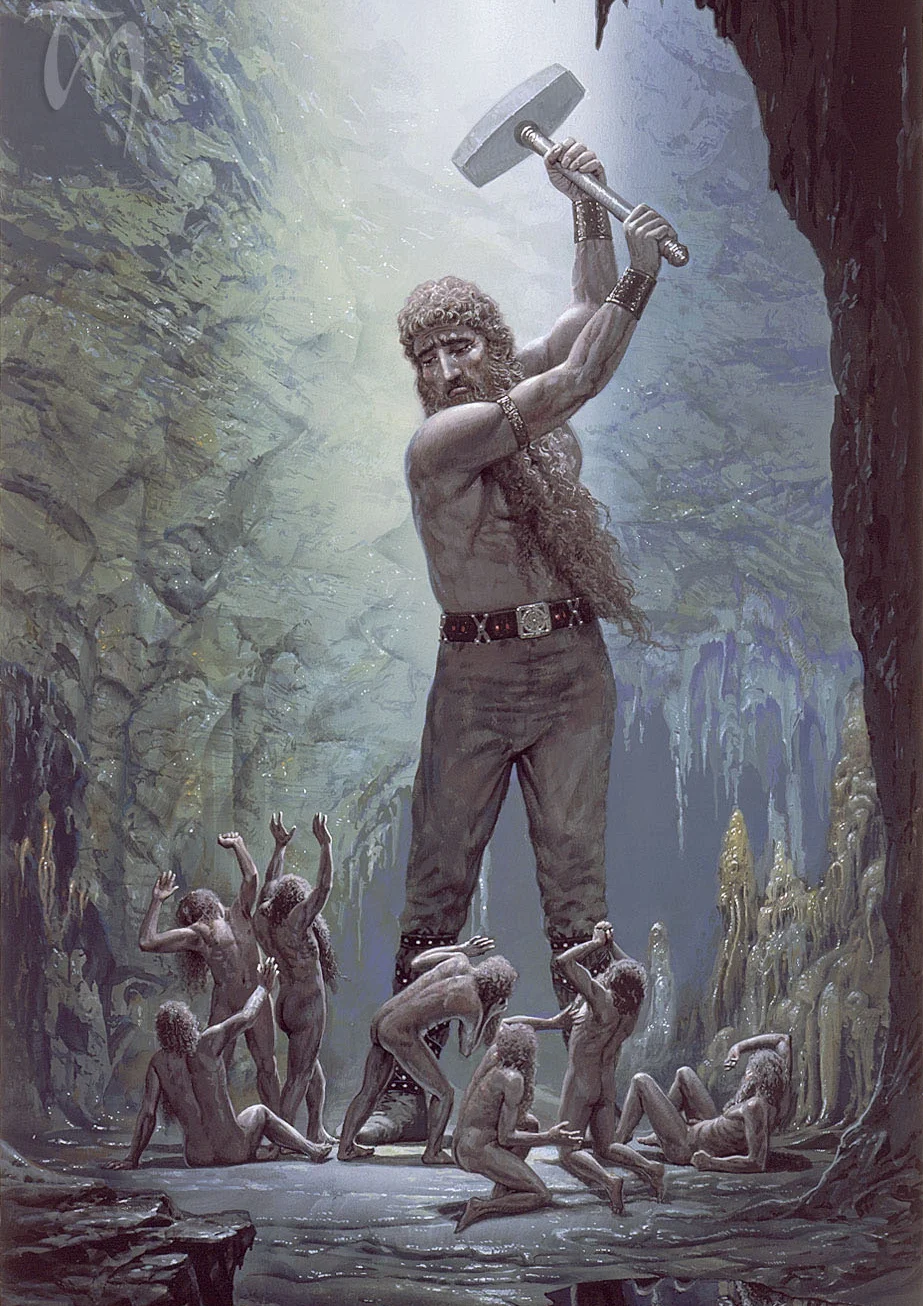

In Tolkien’s invented mythology, Sauron was a Maia, a divine being who served the Vala Aulë, master of craftsmanship and invention. Sauron had an overpowering passion for order and structure, a passion that contributed to his ultimate fall from grace. Sauron was seduced by another Vala, Melkor—later known as Morgoth—whose lust for power appealed to Sauron’s drive for order. He served Morgoth during the First Age. When Morgoth fell, Sauron didn’t repent but renewed Morgoth’s mission.

Tolkien wrote that, at the start of the Second Age, Sauron was “not indeed wholly evil, not unless all ‘reformers’ who want to hurry up with ‘reconstruction’ and ‘reorganization’ are wholly evil.” Sauron seduced the High Elves by offering them access to “science and technology,” as Tolkien put it. The elves desired “knowledge that Sauron genuinely had.” Assuming a beautiful form, he convinced them to make the Rings of Power. He would later control them through the One Ring he secretly forged.

Sauron was driven by a desire to control the world, remake it in his image, and be worshipped as a god. Yet Sauron was never wholly evil. Absolute evil does not exist in Tolkien’s cosmogony. Tolkien wrote, “Sauron represents as near an approach to the wholly evil will as is possible. He had gone the way of all tyrants: beginning well, at least on the level that while desiring to order all things according to his own wisdom he still at first considered the benefit of his ‘subjects.’”

Tolkien’s criticism of “reformers” can plausibly be read as a rebuke of left-leaning activism. Yet the dreams of Silicon Valley are no less utopian, no less committed to a radical social reorganization than any leftist vision. These wealthy men tell us they develop technology wisely. But even a cursory reading of The Lord of the Rings counsels doubt. In seeking to reorganize America, they often seem closer in spirit to the Dark Lord Sauron than the free peoples of Middle-earth.