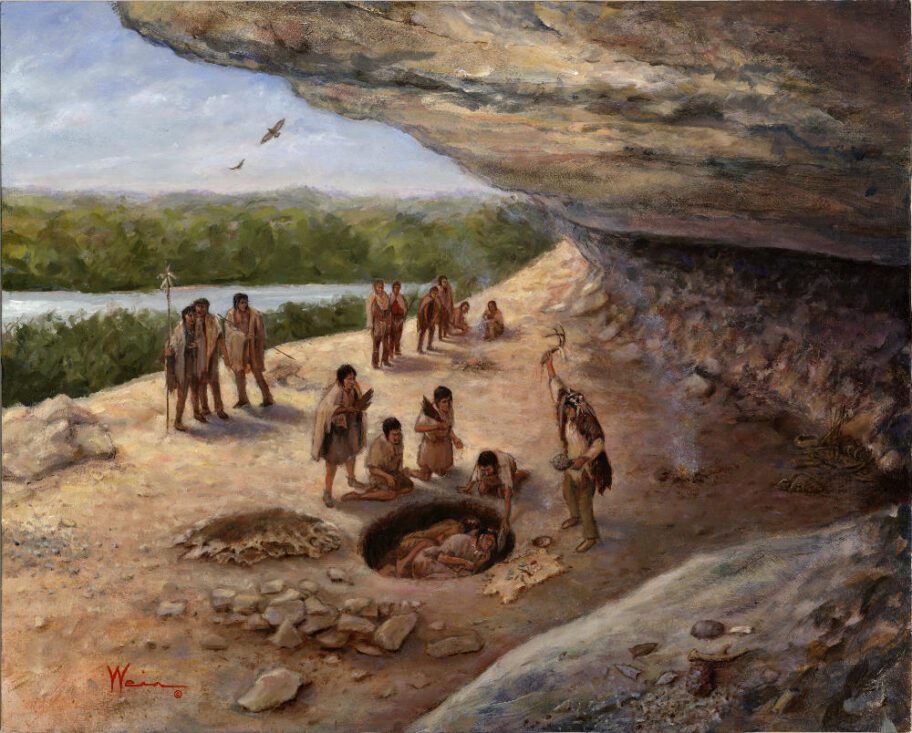

Over eleven thousand years ago, a group of hunter-gatherers congregated to bury two individuals, an adult male and a young girl, in what is now Waco, Texas. In 1970, the burial sites were discovered on the property of Herman and Adeline Horn, thus becoming known as the Horn Shelter; the two bodies are known as Horn Shelter Man and Horn Shelter Girl.

This story begins Thomas A. Tweed’s Religion in the Lands That Became America: A New History (Yale University Press, 2025), an expansive tome that contextualizes what is popularly accepted as the starting point of American religious history—the seventeenth-century arrival of British colonists—in a longer and wider frame of time and space. Rather than treat religion as plainly institutional, religion shows up in the book as a “figurative tool” through which people have navigated questions of life and death for millennia. With this definition, Tweed aims to write an account of the making of the United States that grounds the American nation in a longer story of peoples, places, and traditions on the land we live on.

Tweed, who teaches at Notre Dame, has long advocated for new narratives in the study of American religions. In 1997, he edited and co-authored the volume Retelling U.S. Religious History (University of California Press, 1997), featuring scholars of American religion who offered approaches from perspectives considered marginalized or peripheral. Tweed regularly and readily acknowledges his limitations, as he does in the introduction of this new monograph. “I too have blind spots,” he says, while emphasizing that he wrote this book because “a bigger story that accounts for more evidence” needs to be told.

Because our current conception of American society needs a makeover, Tweed argues, we might consider the Horn Shelter as the earliest instance of religion in what is now the U.S. He notes that even “the unity/diversity motif can’t overcome the embedded implication: there are insiders and outsiders in US religious history.” So Tweed has a different way of framing religion. It is composed of two key components: crossing, or moving, and dwelling, or place-making. (He previously theorized this conception of religion in his 2008 book Crossing and Dwelling: A Theory of Religion.) The burials at the Horn Shelter are thus the first archaeologically recorded instance of people on the continent of North America engaging in religion: a moving people staying in one place to make a burial site, participating in a communal ritual observing life and death.

This definition of religion as crossing and dwelling circles around institutionally recognized forms of religion and reframes movements and phenomena in popular U.S. history through “quasi-religious” frameworks. “Foraging religion” is the movement of early hunter-gatherers, which became “farming religion” as peoples settled and formed societies. The invasion of European “imperial religion” led to the imposition of “plantation religion” on the American landscape. With the construction of factories came “industrial religion,” and in response to U.S. hegemony came movements of “countercultural religion.” People need not be religious to find themselves participating in these religions. If American religious history can be organized through the schema of moving and staying in place, people have been and will be making religious meaning in order to cultivate sustainable lives for themselves and others. Religion has always been at play in history, which has “spiritual origins and ecological significance.”

Tweed aims to write an account of the making of the United States that grounds the American nation in a longer story of peoples, places, and traditions on the land we live on.

Some of these religious forms—what Tweed calls colonial eco-cultural niches—are so focused on profit that they are ecologically harmful and wildly unsustainable. Rather than take for granted the traditionally recognized periodization of American history—the American Revolution, antebellum, the Civil War, and so on—Religion in the Lands That Became America is framed through “crises of sustainability.” The first sustainability crisis occurred circa 1140-1350 in Greater Cahokia (in the Central Mississippi Valley) and Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde in the San Juan Basin, where ancestral Indigenous communities were concentrating into densely populated cities. Climate change, migration, and extensive hierarchical agriculture destabilized these centers, making them unsustainable. This resulted in their decline.

The next three sustainability crises are periods readers are likely familiar with: the Colonial Crisis begins with the first European settlement at St. Augustine and ends with the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Watt’s invention of the improved steam engine at this time is the hinge technological development that takes us into the Industrial Crisis, Tweed’s descriptor for the industrial period. The Great Acceleration is what we have been in since the 1950s, a crisis marked by the globalization of industry and increasingly intensifying ecological devastation. All three of these crises, says Tweed, are unresolved.

At times, the ambitious scope of the book runs the risk of flattening complex conflicts in the face of the ultimate evil of environmental injustice. That isn’t to say that climate change is not dire. But to elevate the sin of environmental damage as something every person is equally accountable for can rhetorically ameliorate the violences of colonialism, segregation, and exploitation that disproportionately affect different groups of people. These violences, after all, are deeply entwined with systems of environmental mismanagement. Tweed walks this balance with careful caution. Yet it’s important to recognize that the kind of “American ethic” toward human dignity and environmental conscientiousness, espoused and encouraged by leaders like Gaylord Nelson, the senator from Wisconsin, in his 1970 Earth Day address, imbues American liberalism with virtue. Appeals to such “American values” can elevate civic participation, and environmental consciousness, as indicators of morality itself.

To elevate the sin of environmental damage as something every person is equally accountable for can rhetorically ameliorate the violences of colonialism, segregation, and exploitation that disproportionately affect different groups of people.

In other words, the elevation of the climate crisis as the ultimate danger, under which every other harm or injustice dissipates altogether, obscures inequities by asserting that everyone is already equal. Tweed does address the unevenness of how climate change impacts communities in his book. Industrial religion, for example, placed immigrant and Black and brown urban working-class communities more in harm’s way than it did other groups, while requiring their labor to develop the nation. Yet history is an approach that seeks to construct a “common” narrative that connects and explains multiple phenomena. Does constructing a different “common” American history shift the way people residing in America understand themselves as a political collective, in a longer duration of time and space—one that does not center an invisible expectation of emulating the Founding Fathers—that can be spurred to action?

Despite my reservations, I’m inclined to hope for a yes. Americans learn over and over again that “figured habitats can prompt wonder and ease suffering, but sometimes can grow socially and ecologically unsustainable.” As a historian, Tweed diagnoses, describes, and explains the issue. He leaves an open question for readers: “Can contemporary faith communities use religion’s figurative tools to restore broken niches and remake sustainable worlds—just, peaceful, and healthy habitats where everyone can flourish?”

Tweed wants to leave an open space for hope. I don’t interpret this question as answerable in our time. My hope is that other readers don’t either. What Religion in the Lands That Became America can do is remind readers of how religion in American society is something longer and more complicated than organized religion. Religion accounts for matters of meaning-making, of creating life and observing death. It has been used for violent gain and wielded too for liberation. This religion does not guarantee the promise of a sustainable world. What we will witness, time after time, are the worlds we make, unmake, and make again.