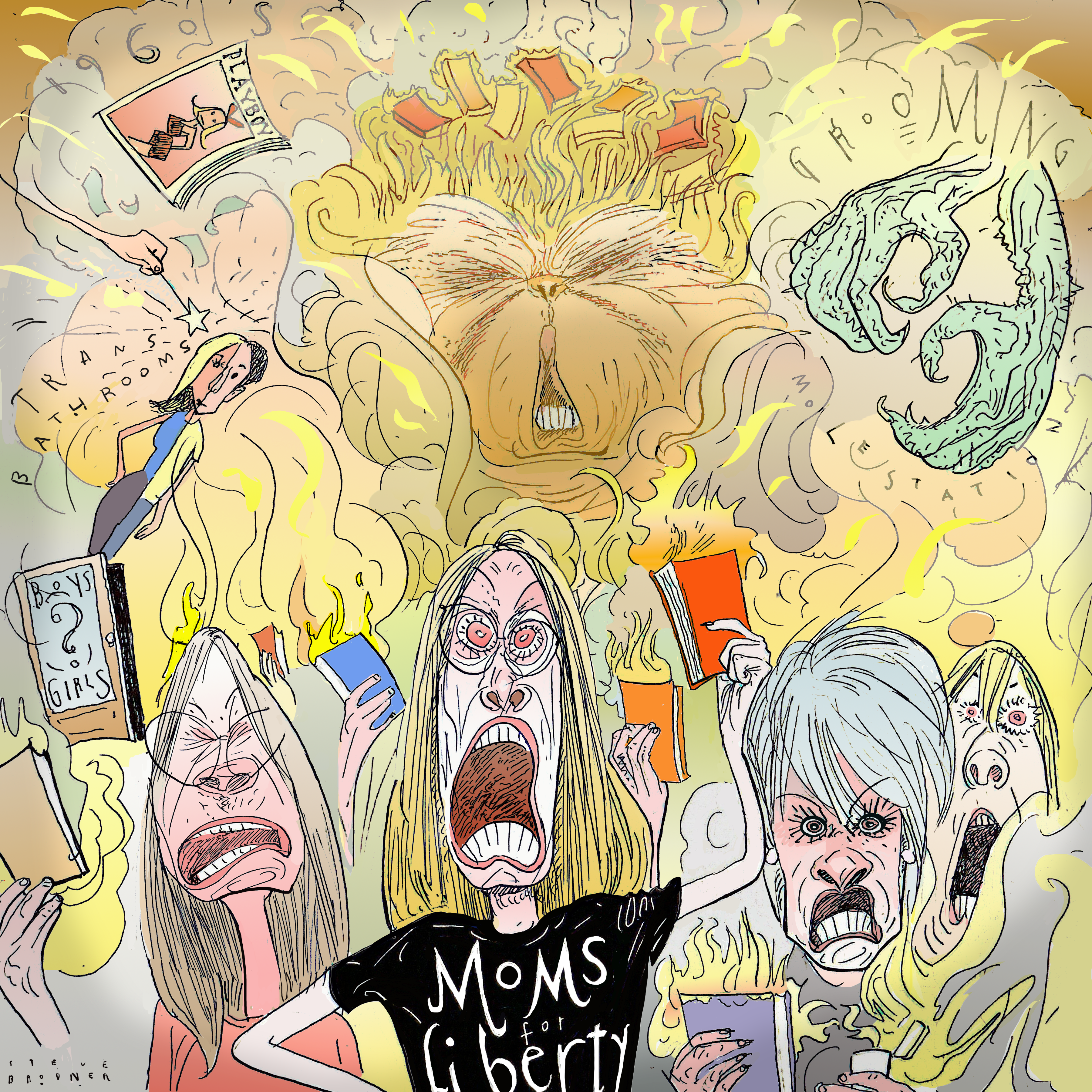

In late August, at a Moms for Liberty event in Washington, DC, Donald Trump falsely asserted that public schools are performing surgeries on children to force them to be transgender. “Think of it,” he said. “Your kid goes to school and comes home a few days later with an operation. The school decides what’s gonna happen with your child. And you know, many of these childs [sic], fifteen years later, say, ‘What the hell happened? Who did this to me?’ They say, ‘Who did this to me?’”

Trump’s comments, imagining schools as nightmarish hospital wards, reflect the right’s recent preoccupation with transgender youth, but they grow from a longstanding suspicion of public education. Much like the campaigns in the late 1960s against school-based sex education, and more recent campaigns against gay rights, these smears don’t just attack people—they attack public schools as amoral hotbeds of sexual hedonism, houses of predation where anything can occur, and—they believe—often does.

The recent campaign by Moms for Liberty (a group founded in 2020 to protest COVID19-related school closures) against the inclusion of LGBTQ books and education, and its ease with Trump’s fantasies about trans surgeries in public schools, have their roots in the conservative religious response to sex education. The first large-scale attempt to introduce sex education into public schools began in the 1960s, thanks to a coalition led by liberal Protestants. According to Kristy L. Slominsky, the author of Teaching Moral Sex: A History of Religion and Sex Education in the United States (2021), these advocates were hardly radicals. They viewed sex education, Slominksy writes, “as moral education and emphasiz[ed] premarital sexual purity, the restriction of sexual behavior to monogamous marriages between men and women, and the importance of framing sexuality by Christian family values.” When Mary Calderone, the medical director of Planned Parenthood Federation of America and a devout Quaker, spoke at the 1961 North American Conference on Church and the Family about the need for sex education, she described it as a responsibility of “the churches.” She and several others who attended the conference (including a Protestant minister) went on to create the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) in 1964, which became the most prominent national organization devoted to disseminating sex education curricula to religious organizations and to public schools.

As R. Marie Griffith explains in Moral Combat: How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics (2017), the SIECUS curriculum reflected what Calderone called “sexual responsibility,” which privileged heterosexual marriage without demonizing bisexuality or homosexuality. Calderone successfully cultivated partnerships with Roman Catholic educators, too, several of whom served on the SIECUS board. They did so despite Calderone’s prior affiliation with Planned Parenthood, largely because she shared many of her Catholic colleagues’ conservative views about the need for clearly differentiated, “complementary” gender roles.

This ecumenical Christian effort (often in partnership with Reform Jewish leaders) ran headlong into a brewing national debate over sexual liberation, hedonism, and moral decline. One of the buzzwords of a growing panic over sexual immorality was the phrase “recreational sex,” a catchall for erotic desire beyond the marital union. Many Americans worried about a corrosion of “traditional” morals, citing the new men’s magazine Playboy, launched by publisher Hugh Hefner in 1952, the growing availability of hormonal contraception with FDA approval of “the pill” in 1960, and the Supreme Court’s 1962 decision, in Engel v. Vitale, barring public schools from requiring students to recite a school-sponsored prayer. In 1961, the Protestant theologian Harvey Cox described Playboy’s regular “Playmate of the Month” feature as “the symbol par excellence of recreational sex,” an emblem of a consumer-driven attitude to sexual intimacy.

This ecumenical Christian effort ran headlong into a brewing national debate over sexual liberation, hedonism, and moral decline.

Yet plenty of other indicators showed that the SIECUS model of “sexual responsibility” was successfully teaching American teens to approach sexuality with Christian teaching in mind. Playboy’s public relations manager, Anson Mount, was invited in Spring 1965 to address about eighty Protestant teenagers from the Kansas-Oklahoma region of the United Church of Christ, gathered for a conversation about “Youth and Ethics—the Revolution in Morals.” (In the mid-1960s, liberal Protestant groups tended to support comprehensive sex education and convened many events to discuss a more “modern” approach to human sexuality.) The UCC was (and is) one of the most liberal Protestant denominations. Probably assuming that he was among friends, Mount explained that when it came to sexual morality, “the whole point of Christianity is missed by drawing up a list of do’s and don’ts.” Mount used the phrase “recreational sex” as he praised the pleasures of premarital sexual experience. The teens weren’t having it. They almost uniformly rejected Mount’s advice. However much conservative Christians critiqued the UCC for embracing “situation ethics,” these teenagers had learned that sexual intimacy should occur only within loving relationships. As one attendee explained, “all the study groups decided the only basis for an ethical code is love.” Nothing about the UCC youths’ response to Mount suggested that they were talking about a revolution. The lukewarm reception Mount’s comments received at the UCC youth retreat may have contributed to his decision to revise subsequent versions of his presentation. By 1967, his public comments on the “new morality” clarified that Playboy did not condone recreational sex and included the threadbare reassurance that Playboy advocated not hedonism but marital fidelity.

Conservative evangelical Protestants found little solace in the sexual probity of those UCC teens. They amplified instead the voices of conservative evangelicals like Gordon V. Drake, who warned in his 1968 book, Is the School House the Proper Place to Teach Raw Sex?,that public school teachers were indoctrinating students with texts by Black intellectuals and corrupting their morals with sex education programs. And just as today’s Moms for Liberty packages its opposition to LGBTQ material (and “critical race theory”) in what it describes in its brief mission statement as an appeal to “the survival of America,” Drake and a cohort of emboldened conservative evangelical Protestants pointed to SIECUS and to public education as toxic purveyors of pornography, “sexual promiscuity,” and “anti-GOD” ideas. As Janice M. Irvine shows in her study of Christian opposition to sex education, more than three hundred organizations soon opposed the integration of sex education into public school.

This marked the start of what Irvine calls “depravity narratives,” wild myths promulgated by Christian ministers and their allies about what happened in classrooms where sex education occurred: that a teacher had intercourse in front of the class (in some versions of this story, a female teacher took off her clothes to display female anatomy), or that a male student, so aroused by the lesson, raped his sex ed teacher after watching a film in class, or that a twelve-year-old boy molested his four-year-old sister after watching a sex education film. Parents, outraged by false rumors, flooded school board meetings to protest the inclusion of SIECUS curricula in their children’s classrooms.

Such efforts were largely successful in attenuating Calderone’s vision of nationwide comprehensive sex education programs. As of September 2023, only eighteen states mandated that sex education be medically accurate, according to the Guttmacher Institute. While twenty-one states required sex education curricula to include information about contraception, thirty-nine required discussions of abstinence.

Starting in the late 1960s, conservative Christian ministers and their allies spread what Irvine calls “depravity narratives,” wild myths about what happened in classrooms where sex education occurred.

Today’s panic over transgender inclusion in public schools borrows from the anti-sex education playlist and adds to it a deliberate confusion of the meaning of gender-affirming care.

Instead of sexual demonstrations in the classroom, the more recent myths in circulation suggest that public schools are facilitating surgical interventions for teens during a gender transition. These allegations are as false as the old rumors about nude sex education teachers. Gender affirming care is often not medical at all. It encompasses recognition of preferred names and pronouns, new haircuts or clothing, and access to safe, appropriate bathroom and locker-room facilities. The minority of young trans people who seek medical means of transition certainly don’t get access to that care through their schools, but rather from doctors.

The idea that public schools, their teachers, and their libraries are sources of dangerous, anti-Christian, anti-American, pro-trans propaganda—and even, in Trump’s tortured grammar, of lurid medical abuses—has nevertheless infiltrated our public discourse. A survey of parents in December 2023 found that while about 85 percent of parents and guardians trusted school librarians and educators to recommend age-appropriate books to their children, another 16 percent believed that librarians should be arrested for recommending certain books to children. Parents who might not support Moms for Liberty have learned from the debate of the last few years that there is something insidious about the presence of books with “LGBTQ+ characters and themes” in their children’s classrooms. Just as in the 1960s, pro-censorship activists today almost exclusively target books that touch on themes of racial justice or gender/sexual justice. A middle school teacher in Illinois said she was forced to resign after activists reported her to the police for “grooming” students (engaging in sexually inappropriate behavior to “make” children gay or trans) because she included This Book Is Gay on a list of recommended titles. Earlier this year, WORLD News Service, a conservative Christian publishing group based in Asheville, N.C., accused the Scholastic Book Club of bullying parents and kids into being gay by publishing a Read With Pride guide for students and their parents. Public schools, the author continued, should instead feature Christian texts that are “Pro-God, Pro-America.”

The idea that public schools, their teachers, and their libraries are sources of dangerous, anti-Christian, anti-American, pro-trans propaganda has nevertheless infiltrated our public discourse.

Perhaps this is much ado about a failing conservative cause. Moms for Liberty has taken a few public relations hits of late. Bridget Ziegler, one of its co-founders (no longer mentioned on the group’s website), was caught up in a scandal in late 2023 involving sexual assault allegations against her husband, Christian (who was, at the time, chair of the Florida Republican Party) and a woman who said she engaged in threesomes with the Zieglers. Ziegler had won election to the Sarasota School Board by campaigning for “parental rights,” including support for “Don’t Say Gay” legislation in Florida. Once the news broke that she had promoted these ideals while engaging in queer sex, other members of the school board “requested her resignation.” The losses of some Moms for Liberty candidates in school board elections over the last two years have also led some political observers to declare it an organization in decline, to the detriment of the MAGA candidates who previously relied on its support. Ziegler, for her part, retained her school board position.

But history cautions us not to dismiss these efforts as the last gasps of a failing movement. As the conservative religious campaign against comprehensive sex education shows, such attempts to portray information about sexuality and gender as anti-Christian and anti-American have lasting effects. The issue of trans-affirming healthcare is historically recent, but the religious right’s assaults on secular education and sexual equality are not.