It’s a friendship begun in grief.

Najla Said, an actress, writer, and the daughter of the late scholar and Columbia professor Edward Said, posted about someone who had “ghosted” her. The impact, she noted in the post, was outsized, an unexpectedly strong reaction she attributed to the death of her father seven years before. “Dying is the ultimate kind of ghosting,” she said to me when we spoke; grief continues to surprise her.

Judith Sloan, a writer and actress who teaches at New York University’s Gallatin School (where I teach, as well), saw Najla’s post and had a strong reaction of her own—the shock of recognition, perhaps, for Judith was writing about the lingering grief she experienced from her father’s and grandmother’s deaths when she was a young girl. She contacted Najla, and the two became friends.

Sloan, the descendant of a family largely destroyed by the Holocaust, and Said, a descendant of a family forced into exile by the Nakba, spoke of Israel and Palestine often, and performed work over the years that addressed the issues directly. How could they not? It is central to their lives and writing, and destruction and exile have remained a constant.

After October 7, however, those conversations became something different. “Volatile,” Judith said. “Petrifying,” Najla told me. So naturally, the two writers and actors decided to make a play about it.

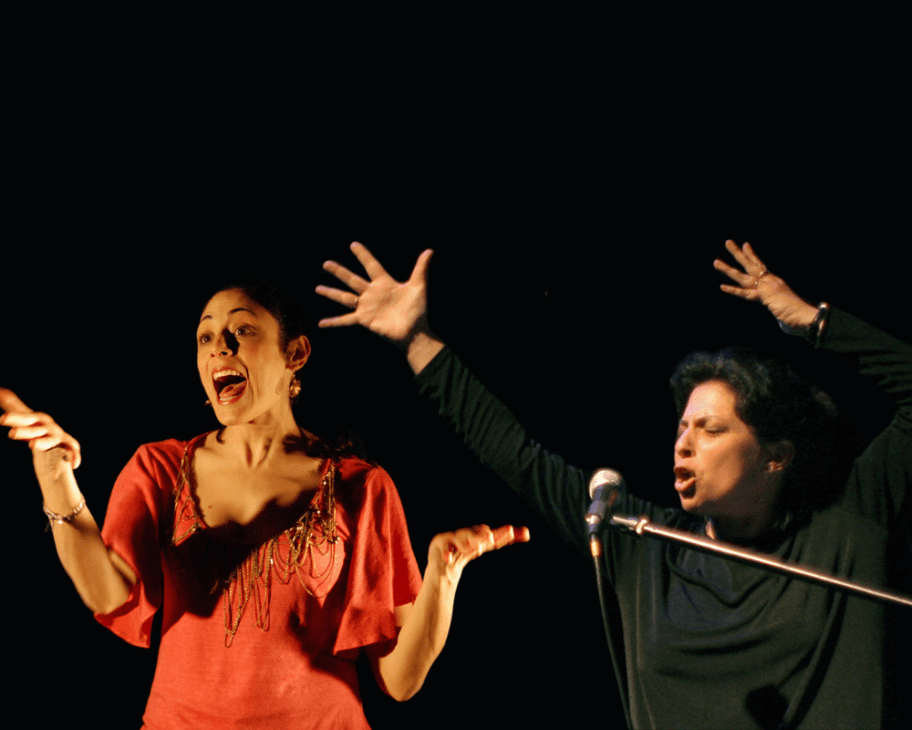

The performance of Imperfect Allies: Children of Opposite Sides I saw in late September, in a narrow slice of theater at New York University, remains a work in progress about Najla and Judith’s childhoods (Najla is in her early fifties and Judith her sixties), family histories, and how these intersect with the events of October 7 and its aftermath. Najla and Judith are still writing and revising, just as the war is still expanding in the Middle East. Part theater, part oral history, part conflict-resolution workshop, the play captures, in its incompletion, the unfolding horror of the present.

The play also stands as the only thing of its kind that my university has staged—the only opportunity to see an honest discussion between “children of opposite sides,” as the show’s subtitle puts it. Other “conversations” about these issues on New York City’s campuses, such as the encampment at Columbia last year, where “Zionists” were not welcome and where the university called the police on its own students, leave most people languishing.

Perhaps this was the thing, sitting in the theater in the fall, that interested me most—that an honest conversation between a Palestinian-American and Jewish-American, one bristling with pain and humor, emerged as possible. I was grateful to Najla and Judith for allowing me to remain in that conversation for a bit longer, by asking them some questions about their work, the situation in America’s universities, the ghost of Edward Said, and the war in the Middle East.

David Sugarman: Tell me about Imperfect Allies.

Najla Said: Well, Judith first reached out to me in 2010. Judith was much younger than I was when she lost her father, but my dad had been sick since I was seventeen. Which in itself is a trauma—living with a sick parent. And so we began to talk about that, and then it sort of evolved out of that. And I think that the Middle East and the political stuff came into it as we continued talking. And then of course, October 7 happened, and Judith was like, ‘I have this project that I sort of put away, but I want to bring back. Would you be interested in working on it?’”

Judith Sloan: I think there’s one thing I want to fill in, which is that in 2010 you were doing your solo show [Palestine]. I had written a piece called Dayenu, in which I was questioning the thing that happens at Passover. In the play I ask, what does it mean to say “freedom” when Israel is impacting so many Palestinians’ lives? So I was already writing about this stuff. Neither of us came to this after October 7 like, ‘Oh, now we’re going to deal with Israel and Palestine.”

And when October 7 happened, I had been doing a show about migration—Migration, Refuge and Finding Home, that was the title of the show. And it was already set for October 28, with a performer from Panama, Wales, me. And then I called Najla probably around October 16 or something, and said, “Let’s turn this into a benefit for Doctors Without Borders. And can you come and be part of a dialogue afterwards?” And do you both remember how volatile everything was?

NS: It was right after October 7. So everyone was really nervous and people were—

JS: Getting fired.

NS: Yeah. And I was petrified, you know, having done my solo show since literally 2008, and it’s called Palestine and nothing ever happened. And no one was outraged or hurt. But now it felt like we’ve taken steps backwards, and that we had to be careful talking. And I think also just acknowledging that people were scared to talk, and be recorded or quoted in any way. It was really important to not allow photographs or recordings or anything like that. And I remember being scared. I remember sitting in that talk-back and my eye landed on a friend of Judith’s who was wearing a yarmulke, and I don’t know who he is or what his politics are. And I was just like, “I don’t want to say the wrong thing.” Because I was scared. And so that was a huge moment of like, my God.

DS: What do you think you were scared of?

NS: Being taken out of context. Because for me, in the days following October 7, speaking of being ghosted—I had already been attacked, blamed. And, you know, a lot of people, I’m the only Palestinian they know. So when October 7 happened, I was just attacked. I was fired by a client in a very unkind way. A friend that I’ve had for over thirty years told me he never wanted to speak to me again.

DS: Someone had fired you by sending an Israeli flag emoji.

NS: Yes. I had been very open. Also, because it’s my personal experience. You can’t really argue with what I’ve experienced. It’s my life. And I had opened up a lot of conversations. Orthodox Jewish people that I knew were like, “You helped me understand a little better.” And it had been all very good. And then after October 7, I just felt like everyone’s anger came out toward me. I mean, everyone in my world. So I was really scared. And I also thought, “Now what am I going to do with my career?” Because Palestine is something I talk about, and it has become too volatile. So I was grateful that Judith had asked me. And I still spoke openly, but in the back of my head I was thinking about what I was saying in a way that I never had before. I don’t believe in violence. I’m not Muslim, I’m not Hamas. And I never felt I had to explain that. And then after October 7, I felt like I was sort of guilty before, you know, anything started.

JS: You know something, Najla, I was also scared in a new way. I understood that opening this stuff up opened up a different dialogue. I felt like we needed to have real, honest conversations with people. But I knew that we didn’t want it recorded, because both of us had already seen people saying things that got completely taken out of context.

DS: What kind of pressure were you facing, Judith?

JS: To condemn Israeli “genocide,” the “apartheid state,” the whole thing. While knowing that there were Jewish professors and Jewish students—a Jewish student in my class whose friend from kindergarten died. I was teaching a radio class in the fall, and I had Palestinian and Jewish students, and they were coming into class, and we were already talking about it in my class, because my class deals with this stuff. A lot of people say, Oh, you shouldn’t talk about this in your classes, but this is my class. We’re doing media analysis of what’s happening in the world. Now a year later, Israel has gone overboard and bombed the hell out of so many people. We kind of knew this was going to happen. I didn’t think it would get this far, but I knew that they would go overboard on October 8. I was just like, “Oh no, what’s the retaliation going to be?” But I wanted to be able to talk to people. And I was also worried about being taken out of context. Because if you say something like, “I could understand being fifteen years old, the only Jews you ever met pointed a gun at you, I could understand being enraged when your whole life is being restricted, bombed, people are dying.” But suppose we say that in a show and that gets taken out of context? “Oh, Judith Sloan and Najla Said support Hamas.”

DS: Speaking of context, I want to talk about the university context a little bit. I saw the work in progress performance in a small theater at NYU Gallatin. What have you made of how universities have handled October 7 and its aftermath?

NS: My father [Edward Said] was a professor for over forty years at Columbia. And the university always supported and protected his speech. Columbia would always insist that the hallmark of liberal education is to have views and to be able to voice them. So for me, this entire year has been sort of horrifying and terrifying in terms of how universities are reacting, because, particularly places like Columbia, it sort of undoes my dad’s legacy in a lot of ways. I mean, if you can’t talk about Zionism…

After all he gave to the university, which touts him as this great thinker who taught there forever—they’re proud of that legacy—but then at the same time, they’re trying to undo everything he stood for. So for me, it’s been really unbelievably jarring and confusing, while at the same time not entirely surprising, because I have been doing events around this issue for years, and they always ask if they should get security. And if I’m speaking, then they want to have someone from the quote-unquote “other side” to balance it. But to this degree, I’m really sort of horrified.

DS: I’m horrified, too. I think it’s been an utter disaster and failure. That was one of the reasons I was so excited to see your performance [of Imperfect Allies: Children of Opposite Sides], because it was the first opportunity of any kind since October 7 to see meaningful dialogue and students having an opportunity to learn and to talk to each other. And I think that you’re right, Najla. I fully agree that questions of Zionism should be debated and need to be debated at Columbia, where your father shaped that debate. I also think student safety is really important. And I think in some cases that didn’t happen, in terms of the ways that Jewish students felt at NYU or Columbia, and also in terms of students getting arrested. Presidents should be modeling discourse and disagreement, not calling the police. And so I’m curious how the two of you managed to do what these schools have not: create a space where conversation is possible, and where students feel safe to learn and listen?

NS: I think what’s unique about myself and Judith is we come from a theater background, where you have to make yourself vulnerable and you have to be truthful. Over the past year, I’ve realized I’m very lucky to be in a world where you have to listen. I mean, the whole “acting is just listening and reacting truthfully” thing is true. I’ve been lucky that I’ve done Palestine so many times, in so many places, where people are not used to hearing someone be so vulnerable and honest. This precedent of non-judgment has not been really present in a lot of these attempted “interventions” or whatever. It’s usually about, “Let’s get one person from each side to speak, and we’ll debate international politics.” But if we just focus on allowing people to have their truth, and not cutting them off—that’s possibly why it works.

These students are young. They’re at an age where their frontal lobe is not fully developed. And so there was a lot of reactiveness and defensiveness, and I think what we try to model and teach is that we can have these conversations and speak our minds, and we don’t necessarily agree, but we can listen.

JS: We’ve had a person who was a former IDF soldier sitting with a Palestinian woman whose sister was killed on the West Bank. And so we have had very, very different people in the room at the first five events in New York, and they were packed. And it happens at every one of our events. We let people talk. We don’t monitor them, we don’t control them, we don’t colonize or cannibalize their conversations. We let people have a conversation and we model ours and we model our performance, and then people can go away and continue the conversation.

As for the question of what the university is doing, I’m going to challenge everybody that’s reading this article to stop thinking that way. Because how did this play happen? It took a tremendous amount of work on our part. [Sloan received a small grant from the Gallatin School of Individualized Study in December 2023 to embark on this project, which would focus on conversation between herself and Najla Said, specifically for developing a performance between two New Yorkers, one Palestinian and one Jewish.]

I studied with a rabbi once who said, To see your enemy as human is a truly painful thing.

NS: In 2011, after Palestine, my show, had run off Broadway, I was invited to a private high school in New York. One that I know very well. I didn’t attend it, but I knew a lot of people who went there. And it’s a largely Jewish student body. But it’s also known to be progressive. And I was asked to perform my play for the high school, but the parents and the faculty wanted me to do it for them first to see if it was okay. And this is after it’s already run off Broadway and had reviews. So for me, I feel often that these restrictions are specifically about the Palestinian person somehow being “offensive.” And I did it at the time. I auditioned for the faculty and parents, and then I did it again for the students. But if that happened to me now, I would say no. And I think that it’s something that needs to be said. The nervousness around this issue is very much because of the Palestinian and not because of anything else that these events are.

JS: Exactly. Often you’ll see schools will have some “dialogues” between Jews and Muslims. There’s a lot of things like that.

NS: That’s a red herring. That has nothing to do with what’s happening.

DS: Judith, you’ve been teaching for more than twenty years. And Najla, your father dedicated his life to the university. How does this make you feel about the roles universities have played in all of this?

NS: In a lot of ways, my dad made it okay to talk about all of this. Because people—and this is something I remember from when I was a kid—a lot of people just assumed he was a terrorist. But I think one of the things he was very good at was, you know, people accepted him because he dressed nicely and spoke English without an accent and—or maybe had a little British accent, but that’s not a liability, exactly. And the irony is he went from being sort of a villain to being the one person that people felt okay listening to. That was true even though his views could be, I don’t know, maybe radical to some people—even though they were just calling for coexistence and peace, while still calling out the Israeli government for its atrocities, which have always existed.

And when people hear that I am this person’s daughter, there’s either a sense like, “Okay, she’ll be okay,” which is bizarre, or else it’s the opposite, where it’s like, “This person is this person’s daughter, and that makes us uncomfortable because he very unabashedly spoke out.” I think if my dad hadn’t started the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra with Daniel Barenboim [an orchestra made up of Arab and Israeli musicians] toward the end of his life, I think I would still be considered, you know, maybe not so safe. But I think that project brought in a lot of people who were skeptical of him as someone who wanted to get rid of all Israelis or something, which he never was.

I was just attacked. I was fired by a client in a very unkind way. A friend that I’ve had for over thirty years told me he never wanted to speak to me again.

So I’m seen as one of those two things, and it’s exhausting. Because I’m used to either being discriminated against because of him, or overly accepted because of him. But I do think that he left behind a legacy of someone who was willing to engage with the quote-unquote other side.

And in terms of Columbia, I mean, my dad’s office was in Hamilton Hall [a Columbia University building that was occupied by protestors in the fall] for thirty years. And it’s been disappointing and hurtful, because it feels like more things could be talked about twenty years ago than they can now after October 7. So I have taken a lot of it personally, because I feel like they’re trying to undo everything he tried to do. But I think, as Judith said, these are administrators, they have to answer to donors. So I think universities need some people like us to help them because otherwise they don’t know how to touch the issue because they’re not basically educated on it.

DS: What do you feel is the most urgent thing you want to communicate via this show?

NS: I think for me personally, and this goes with all my work, it’s that you cannot generalize what an Arab is, what a Palestinian is. I come from an urban family. My family is from Jerusalem. And there was a whole culture, and there’s a variety of people in our culture. And it’s worth listening and learning about who we are. And you’d be surprised at how much you will learn about my family and about me and about Palestinians in general. I try to be very open about my family, where we’re from, who we are, and that there are infinitely more people with their own stories, and we don’t just all boil down to one thing. And that there is a difference between those of us in the diaspora and those of us still in Palestine. And I think just accepting that Palestinian Americans are Americans too. Listening to just one person’s story can flip a whole narrative on its head.

JS: I mentioned earlier the Dayenu radio piece that I produced. There’s a line in there where I say, “I studied with a rabbi once who said, ‘To see your enemy as human is a truly painful thing.’” Sometimes I feel overwhelmed, and it’s not easy. I have to be willing to say, “You know, Najla, this is really painful for me to hear.” Or listen to her say, “This is really painful.” You have to be willing to be pained to have these conversations.