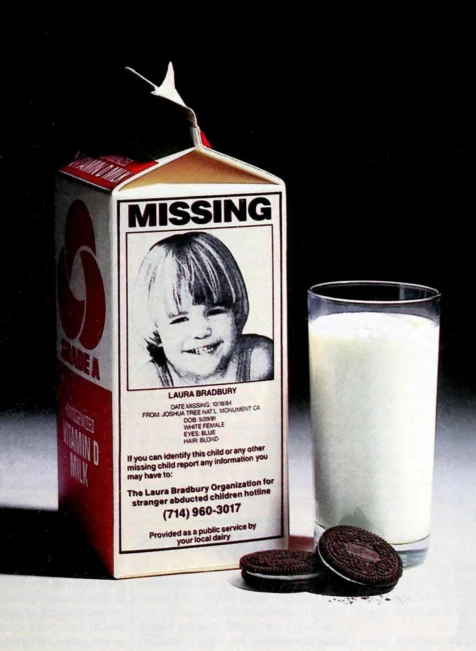

Growing up in the 1980s, I used to eat breakfast with the grainy faces of missing children staring back at me. Printed on the sides of milk cartons, these photographs of abducted children instructed me to fear strangers. At school, we memorized a script with a family code word to use if a stranger ever offered us a ride and said our parents were okay with it.

I had mostly forgotten about the milk-carton pictures until October 7, when my daughter, a freshman at Columbia University, texted me a photograph of larger-than-life milk cartons, lined up one next to another on the main campus lawn. Each was imprinted with the face of a hostage taken by Hamas. Later, I learned this was a traveling exhibit called “Memory Lane,” a collaboration between national organizations and pro-Israel students, based on an installation conceived by Chicago philanthropist Jeff Aeder.

My daughter was confused: “Does the milk carton have any significance?” she asked. It took me a minute to recall the milk cartons from my childhood, a memory she was too young to have. The practice of printing missing children on milk declined in the late 1980s, with the last missing child appearing on a milk carton in the mid-1990s, a decade before my daughter’s birth.

Strange, then, that the milk-carton exhibit was mounted on a college campus. The comparison the creators wished to evoke was surely lost on the college-age passers-by. But more than a symbolic misfire, the milk carton suggests a deeper parallel between American Jewish life since October 7 and the missing-children craze of the eighties.

The high-profile kidnapping of Etan Patz in 1979 triggered a media and political frenzy around the supposed rise in the abduction of children. Over the next five years, news outlets devoted thousands of hours of programming to the cause, and Ronald Reagan appointed a task force and eventually designated National Missing Children’s Day to draw attention to the problem. Yet as scholars have shown, while the media and political leaders portrayed kidnapping as an epidemic, in truth it was episodic. Nearly all cases, it turned out, involved custody disputes among family members. Kidnapping by strangers was vanishingly rare.

Even so, new laws and disciplinary measures to combat child abductions gained public support. Often described as pro-family, these laws gave legal force to fears about strangers. They identified family dysfunction and sexual deviance as likely causes for kidnappings and raised suspicion about people who did not look like they belonged. Warnings about “stranger danger,” and the laws to guard against it created their own reality, including one more justification for the carceral state.

A small sociological literature about “moral panic” supplies a helpful lens to understand why politicians, the media, and even the dairy industry leapt to stop a largely invented problem. Stanley Cohen coined the term “moral panic” in the early 1970s after witnessing a series of youth rebellions in England met by an outpouring of press attention, policing, and legal reform. “[M]oral panics” Cohen argued, “are condensed political struggles to control the means of cultural reproduction.” In his view, these panics sought to identify and control deviance precisely when the lines between deviant and normal behavior blurred. Moral panics achieved their goal by establishing a social order that reflected the priorities of authorities. By portraying every child as a potential victim of deviance, from mothers who worked outside of the home to people identified as sexually different, the missing-children craze served as a rationale for beating back social change.

What does this all have to do with American Jews and college campuses? No matter the intentions of their creators, the rows of milk cartons displayed at Columbia reflect, and contribute to, the moral panic over anti-Zionism and antisemitism that has taken hold of American Jews. For as Cohen and later theorists explained, moral panics generate a rationale for suppressing and criminalizing diversity.

Columbia University has been ground zero for moral panic. The New York Times and other media outlets have turned the university into a veritable beat, with blow-by-blow coverage of protests and encampments. At the same time, politicians and Jewish communal leaders have invoked the protests to achieve ends that largely preceded October 7.

Congressional hearings and efforts to pass new legislation routinely refer to Columbia as a reason to reform anti-discrimination laws and as grounds for castigating higher education and its leaders. The sense of urgency, however, belies many politicians’ long record of opposing DEI initiatives and “wokeness” in higher education. When she opened the first House hearing on campus antisemitism, Rep. Virginia Foxx (R-NC) said as much, explaining, “For years, universities have stoked the flames of an ideology which goes by many names—anti-racism, anti-colonialism, critical race theory, DEI, intersectionality….” For her, DEI, as well as attempts to curb bigotry and hate speech, were meant to be bad things that she simplistically and strategically blamed for creating hostility against Jewish students on campus. Yet by the time the congresswoman was through, it was clear that speech codes, limitations on free speech, and victim-coddling were not actually the enemy as much as universities themselves, lambasted for doing these things too much for certain groups and not enough for others, like pro-Israel Jewish students.

But in a moral panic, reasonable worries about child safety or the safety of Jewish students become instrumentalized to score political or legislative victories or to trample on people’s rights and freedoms.

Likewise, Jewish communal organizations have showcased the protests to amplify longstanding claims that anti-Zionism is inseparable from antisemitism. Some organizations, for example the Brandeis Center, started advocating well over a decade ago for legislative reform and executive actions to broaden the scope of antisemitism to include anti-Zionism. Others, like the ADL, have insisted for close to forty years that anti-Zionism is a form of antisemitism but have hesitated to support legal tools to suppress anti-Zionism, like state-level anti-boycott legislation. Yet decades of caution about criminalizing anti-Zionism or using civil rights law to deem it as impermissibly discriminatory unraveled after October 7, with once-passionate convictions about free speech and protections for dissenters swept under the rug of panic.

Scholars who write about moral panics caution that valid concerns almost always underlie them. No one could possibly dispute that a child gone missing is a thing to fear. Likewise, one cannot—and should not—deny the pain of families whose loved ones were brutally taken (and in some cases raped and murdered) by Hamas. And one cannot—and should not—deny the ugly incidents on college campuses that have viciously targeted Jewish students.

But in a moral panic, reasonable worries about child safety or the safety of Jewish students become instrumentalized to score political or legislative victories or to trample on people’s rights and freedoms. In the name of the panic, a judicious response to a legitimate concern becomes impossible.

In the end, the symbolization of October 7 through missing-children milk cartons is perhaps rather apt. In the United States, we are living in a moment when the horrors of October 7 have moved well beyond themselves, transforming concern about Israel’s treatment of Palestinians into a form of deviance that requires discipline. Just as political leaders, religious leaders, and media pundits exploited anxiety about missing children to regulate behaviors, mete out punishments, and pass new laws, so too are we seeing today’s leaders become—in the words of two sociologists—“moral entrepreneurs.” Using the well-trod path of panic, they seek to achieve communal, political, and legislative ends that “discredit spokespersons who advocate alternative, opposing, or competing perspectives.”

If the milk cartons succeeded, despite themselves, to expose today’s moral panic, they also achieved a second equally inadvertent end. In their bafflement about the exhibit, my daughter and her friends paused to ask questions. Indeed, while I was plumbing my childhood memories to answer my daughter’s question about the link between milk and hostages, she texted another question: “Can you send me some recent articles to read about the Israel Palestine situation?”

As she recounted to me, she and her friends talked about a vigil they had witnessed on campus the night before, when a quiet gathering of students read the names of some of the tens of thousands of Palestinians killed since October 7. And they thought about where vigils and protests were taking place, and why the university had shut down once-public spaces. And instead of experiencing fear, they felt curiosity, the only sure antidote to moral panics.

The milk cartons were, in their way, good activist and propagandistic art. But that’s not the university at its best. Universities have the requisite tools to resist moral panics, for the simple reason that they value curiosity. I suggest that instead of caving to pressure from politicians, the media, or some Jewish communal leaders to join the panic, university leaders redouble their commitment to fostering inquiry and responding to differing perspectives as reason for discussion, not discipline. The terrible injustices and acts of violence in Israel, Gaza, Lebanon, and beyond should not be milked to justify assaults on freedoms in the United States, nor to create a proxy war on university campuses.