It was not Charles Taylor, the noted nonagenarian Canadian philosopher, who lamented that “Man needs a metaphysics; / he cannot have one.” Instead, it’s the great contemporary poet Frank Bidart, meditating on his own—and “man’s”—felt lack of connection to something beyond us: a community, a divinity, a Nature that might give purpose to this world. That lack—and the ways that poets, poems, and poetry address, depict, and make up for it—drives Taylor’s expansive new book, Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment (Harvard University Press, 2024), whose chapters on nineteenth- and twentieth-century poets weave attentive, line-by-line readings (from English, from French, and from German, with translations) with intellectual history. In brief, Taylor argues that major poets in Western European languages since about 1800 have tried to create, or discover, or make available through poetic language, emotional and spiritual ties that link people to something: a God, a version of Nature, a purpose that organizes our time and our space. These ties once came from organized religion; now they don’t, or not without question, and poets take the lead in a civilization-spanning quest to get them, or get them back.

Taylor’s arguments end up easy to follow, and largely persuasive, but—for readers who already know these poets—only sporadically surprising. When Matthew Arnold wrote in 1880 that “most of what now passes with us for philosophy and religion will be replaced by poetry,” he summed up half the thesis of Taylor’s volume; when T. S. Eliot summarily rejected Arnold’s thesis, quipping, “Nothing in this world or the next is a substitute for anything else,” he summed up the rest. And yet the divinity, here, lies in the details. In poems, in readings of poems, and in the philosophy of religion, Taylor shows just what aspects of our supposedly lost whole—the whole self that in prior epochs was built of religious “enchantment,” to use Taylor’s word—poets have hoped to find, or build, or restore. He ranges from Hölderlin and Wordsworth (good, obvious choices) to Czeslaw Milosz (a good, less obvious choice).

Taylor’s Sources of the Self (1989) and A Secular Age (2007) explained, clearly and at great length, how we got to a point where each of us feels that we have to construct our own way to live in this world. Taylor himself has chosen (or feels chosen by) a version of Roman Catholic thought compatible with the liberal politics of what he calls multiculturalism (see his fine 1992 book with that title). His own life as an Anglophone Montrealer may give special valence to his decades-long effort to see how people with various senses of the good life, various orientations towards the sacred, might learn to live together.

Taylor’s new book (which does not mention Bidart, but could) starts with the lack of togetherness that modern, disenchanted, empirically-guided life entails. At least, so the Romantic poets, in English and German, declared. They had precedents, too: now “times are altered; trade’s unfeeling train / Usurp the land and dispossess the swain,” wrote Oliver Goldsmith in 1770. Poets who came after Goldsmith, and especially after the French Revolution, aspired to make a substitute, a kind of prosthetic for old, lost connections and certainties: poetry itself, calling on the still mysterious resources within language, would become, Taylor writes, a “collaborative work of reestablishing contact, communion between ourselves and the world.”

Rather than prove by logic that nature could come—or come back—to us, Romantic poets wanted to prove it “through the force of the experience of connection.” But they had to do so in language, which means that their efforts involved “an inescapable hermeneutic dimension,” and potentially “endless interpretive dispute.” If you want to use language to take us to a realm beyond science, and logic, and worldly proof, you’d better get ready for readers to disagree, indefinitely, about what you mean.

Nevertheless, a true poem—for Taylor, as for Friedrich Hölderlin, and John Keats, and Christina Rossetti—“gives us a vivid sense of what it is like to be in the situation of the lover, the bereaved, the devout seeker.” It makes connections (at the least) among people (if not between people and Nature). And, of course, we cannot prove the connection valid: we can only say how it feels. As the poet and critic Randall Jarrell put it: “The best critic who ever lived could not prove that the Iliad is better than ‘Trees’; the critic can only state his beliefs persuasively, and hope that the reader of the poem will agree—but ‘persuasively’ covers everything from a sneer to statistics.”

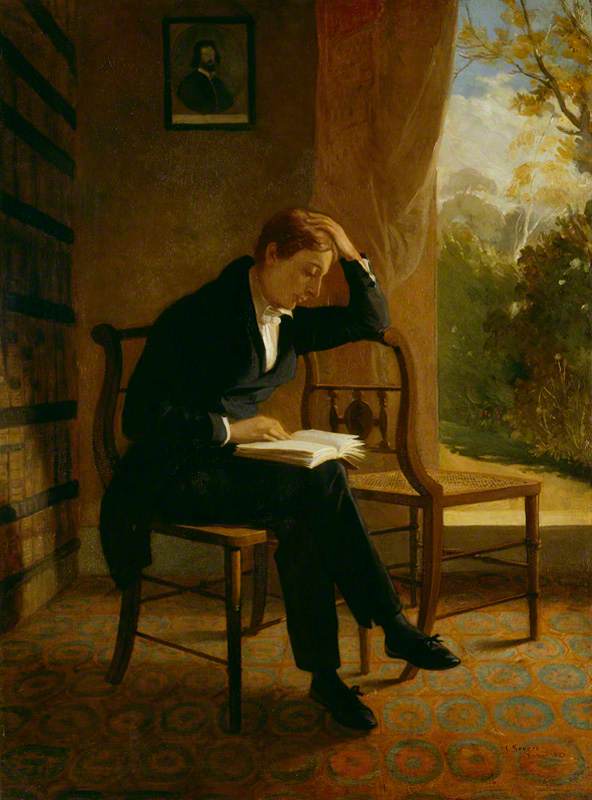

Those feelings, and those hopes, amount to Taylor’s “connections,” whether or not they seem cosmic: they inhabit “the meaning of an interspace—the situation of a human being before a given scene,” in a way that gives the scene itself some “meaning for our purposes, our fulfillment, or our destiny.” Nice work, if you can get it: German Romantics and their less systematic English and French counterparts tried. They even constructed a theory of language by which the poet “translated” the forms and meaning of Nature into terms that humans could understand. But these terms—unlike, say, the terms of Thomas Aquinas—did not have to convey any literal meaning: they did not require “any picture of cosmic order.” That’s Taylor on Keats, whose Urn believed truth was beauty, though he himself retained some doubts; as for metaphysically revealed truths congealed into doctrine, Keats wanted nothing to do with them (see his sonnet on hearing church bells).

Keats and Gerard Manley Hopkins disagreed on that front, but they both found “goodness and beauty in reality itself, not just in its portrayal”: poetry meant to bring out, even to emulate (or to translate) the experience of beauty already available from the contemplation of a kingfisher, or a stubble field. These Romantic connections to nature stand, for Taylor, in contradistinction to those of Gustave Flaubert or Samuel Beckett, who found beauty only in the means of portrayal, in the artfulness of art, not with so much as against the real world. “Gesang ist Dasein,” “Singing is being,” Rainer Maria Rilke declared. It’s that leap of faith, or faith in language, or faith in art, that the enemies of Taylor’s connections resist: in the name of a secular logic, or an inconsistent, eschatological idol called History, or a Pyrrhonism so corrosive that no art survives its touch.

Taylor, and most of his poets, write against such skepticism. One exception is Baudelaire, whose poems, for Taylor, represent “the most profound form of despair,” in which “we have lost a grasp on what it is we are missing.” The Baudelaire of Paris Spleen feels “paralyzed, incapable of acting.” Even his sense of how time passes has gone haywire: modern life keeps “imposing various kinds of alien time use, or time sequencing,” such as alarm clocks, or assembly lines, or X (formerly Twitter). A poetry that gave us—or gave us back—a sense of lived, purposeful time would have to assume “something of the nature of ritual,” with or without the ritual repetitions of rhyme and meter.

Taylor’s new book starts with the lack of togetherness that modern, disenchanted, empirically-guided life entails.

Taylor calls for that kind of ritual, or substitute for ritual. Poets of recent decades who play no role in his book, and have little use for theology, answer the call. Consider the first poem in Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems (1964):

If I rest for a moment near the Equestrian

pausing for a liver sausage sandwich in the Mayflower Shoppe,

that angel seems to be leading the horse into Bergdorf’s

and I am naked as a tablecloth, my nerves humming …

It’s like a locomotive on the march, this season

of distress and clarity

and my door is open to the evening of midwinter’s

lightly falling snow over the newspapers.

Clasp me in your handkerchief like a tear, trumpet

of early afternoon! in the foggy autumn.

O’Hara’s campy self-talk at the southeast corner of Central Park anticipates a secular Christmas, a seasonal return (autumn looks forward to midwinter), and a self-transcendence no less delightful for feeling ridiculous. Why would a locomotive march, or an angel lead a horse?

Taylor finds almost no place for the comedic, nor for the merely, frivolously sociable: but poets like O’Hara do. O’Hara’s thoroughly re-enchanted moment comes with its own engaging free-verse rhythms, a way to reorganize time that has little to do with (for example) blank verse, and less still to do with orthodox religious observance, except in a kind of Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, I-love-Christmas-shopping kind of way. Nonetheless (to quote Taylor) such compositions in verse “offer a connection to a larger pattern in time which can inspire, even exalt us, and put an end to spleen.” So do the free-jazz patterns of the contemporary poet and cultural critic Fred Moten, whose work (again) falls outside Taylor’s catchment area:

a river is studio agitation through one window,

aloft in rock bottom’s soft support and

rumble, a room, a cell alight in the way the

walls walk off in juba’d pat and tiling,

the pattern on the river floor all absolute

and indiscernible unless you walk it, in the

river, as the river, as all this rotary soar of

the dammed and held, sous vide in second

linearity, parading in this tuba’d lining

out of the basic line all and against itself

“Indiscernible unless you walk it”: you can’t set down rules in advance for this kind of ritual, any more than you can tell a river where and how to flow—you have to be there.

And here the omissions in Taylor’s model of literary history feel more serious: what if, rather than feeling that your generation has lost some older connections, you feel that Western civilization—which kidnapped and chained your great grandfather—never offered you such things? Does that difference make a metaphysical difference?

Moten’s other writings say it does. Those other writings connect his verbal innovations to specifically Black experiences of time, and radical politics, and interpretive difficulty: they’re must-reads for those writing about poetry now. Nothing like them shows up in Taylor, whose modern poets, alas, are all white dudes. And yet Moten’s jazz-informed sense of ongoingness, his changing same, also implies a kind of resistance to certainty, “a locus of Non-Being which underlies and makes possible the appearance of reality.” That’s Taylor on Stéphane Mallarmé, whose search for new life through ineffable ritual seems to be Moten’s, and O’Hara’s too.

And here the omissions in Taylor’s model of literary history feel more serious: what if, rather than feeling that your generation has lost some older connections, you feel that Western civilization—which kidnapped and chained your great grandfather—never offered you such things? Does that difference make a metaphysical difference?

As Taylor enters the twentieth century, his canon cleaves in two. Some of his poets, like Mallarmé, try to imagine, or invent, or simply pine for, a poetic language that would separate itself from prosaic English and French and so on, and from curbstones and tire treads and telegraphs. Such a language of “absence-in-presence,” of “time-extended place,” would be less like the speech O’Hara thought he was using than like Heptapod B, the brain-breaking language of simultaneity and transcendence in Ted Chiang’s influential science fiction tale “The Story of Your Life.” Some versions of Christian belief promise to do the same thing, presenting their “God as present to all times,” to use Taylor’s words, as well as made flesh right now. Taylor shines as he unfolds that belief in T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, a collection now nearly as underrated as it was once reflexively revered for its efforts “to apprehend / The point of intersection of the timeless / with time.” Here “poet and philosopher operate together,” and the experience of aurally charged language might do what dogma cannot.

The other poets in Taylor’s modern dichotomy attend less obviously to transcendent experience, and more to what we ought to do for one another: they are poets of ethics, called to “defend the intrinsic worth of any identity against the demands of an instrumental rationality.” I might have offered Adrienne Rich as such a poet. Taylor instead picks Czeslaw Milosz, who like Taylor backs up his sense of ethics with a sense of obligation to something beyond this world, a “salvation through beauty,” and a “catholic faith … in dynamic struggle with doubts.”

Milosz makes good reading when you feel like your side has lost, like history has dealt your sense of the good, and the true, and the beautiful a losing hand (see Sara Marcus’s recent book on the topic). Post-1980 Rich makes good reading here too, though without the transcendental scaffolding whose intellectual origins Taylor makes it his business to trace. And Rich, like Milosz, like Taylor, finds an ethics—and a reason to write—in (as Taylor puts it) “the idea that the human person by its very nature commands respect.” Following Hans Joas, Taylor finds that idea not just in moral philosophy but in political history, in the rise of eighteenth and nineteenth century social movements, from antislavery to anticolonialism to … wherever we are.

Taylor’s last two chapters step away from poetry and poetics, from lyric and ritual, entirely in order to seek sustainable, explicable grounds for a modern public ethics, one that recognizes our need for “a powerful common identity” without finding value only in “a tribe, or a group of tribes.” These grounds may emerge from nonhuman nature, as understood by Annie Dillard, or from Pope Francis’s call for “interfaith action.” Or, perhaps, from First Peoples’ sense of what we owe the sea and the land, as in Inuit poet dg okpik’s uneasy merger of frangible, illimitable nature with her mortal, literate body: “still, on the page grow spotted mushrooms and morels … The change of the ice age with purpose as the warming earth today / But I take heart in sun along with the core of a gingko tree’s light.”

No one should much fault Taylor—who has read, taught, and long considered more philosophical prose than I ever will—for bringing to this big book a less than multiversal familiarity with post-1945 poetry. He’s done a lot here, and he’s usually right, not least in his sense of how “ritual invocations” that let us imagine meaning-making connections—to one another, to nonhuman nature, and to something else somewhere out there in space-time—“survive among our poets.” For those of us (not all of us) who look back on ancestral certainties, as writers from Wordsworth to okpik have done, something seems gone, some visionary gleam: poetry (the right kind of poetry) can help us imagine what to put in its place.