I left the dying capital for the dead one, New York City for Vilnius, to do three related things. First, cover a conference, part of the centenary celebrations of the world’s preeminent organization for the study and preservation of Yiddish; second, consider the relationship between these two cities, one the fading center of postwar Jewish life, the other the decimated center of prewar Jewish life; third, spend a June weekend away from New York, my hometown, so as better to see it—to gain some distance and thereby clarity. Because I felt, in the place I was born and raised, a deepening disorientation. It was the mayoral elections and the mood since Trump’s reelection and the quiet on the university campuses and the assaults against Jews in Brooklyn and the clamor of the conversations about Israel and Gaza and my wariness towards communities where I’d once been at home that made me feel, inchoately, a sense of an ending.

And so I spent the nights walking the narrow streets of the dead capital and the days in the city’s Soviet-era central library, covering the centenary anniversary of the Yiddisher Wissenschaftlicher Institute, or YIVO. Founded in Vilnius—or Vilna, in the mama lashon, the mother tongue—in 1925, YIVO is today located in New York City.

As part of its centenary, YIVO had organized a conference that brought some hundred or so Lithuanian educators to Vilnius for a long weekend. I met this jovial group in their country’s capital, and we shared lunches in Ukrainian restaurants and cocktails in the catacombs beneath the city’s castle. In an auditorium in the library, meanwhile, we learned about the country’s Jewish history, equal parts murderous and amazing.

This is something I’d traveled to Vilnius to learn about, too. Because the city had arguably been, until World War II, the global center of Jewish life. Not just religious life—sages, yeshivas, sofers, shuls—but also Jewish secularism and modernity—bundist and communist revolutionaries, Zionist thinkers and organizers, Jewish Enlightenment. The very same -isms and ideas that define the debates within the Jewish community today. Back home in the dying capital of New York City, Jews were arguing in language lifted directly from this earlier time and place: Zionism or secularism or socialism or traditionalism or diasporism, ideas born into conflict a century or more before. Such conflict seemed to me the mark of a robust and diverse Jewish community. To be a Vilna Jew was to be any kind of Jew, and to still have a vibrant home.

Such a vitality had once defined New York City’s Jewish community, too—a vitality and sense of doikayt, or hereness—but lately it felt less so. Since the war between Israel and Hamas began, the city had come to feel different—less safe, less convivial. So much so that my core self-conception as a “New York Jew” appeared increasingly trivial. Perhaps it had always been thin, this less than century-old-idea, but still, if asked to describe the world I was born into, that I’d inherited from my parents, “New York Jew” would do a good deal of work. And suddenly it didn’t seem to describe a way of life or a form of community so much as a branding gimmick, or a historical hiccup, or a failed utopia.

So I’d left the dying capital for the dead one, hoping it might help make sense of things. As if there is any solace to be found in our dead and dying homelands.

I don’t want to overstate the similarities between Vilnius, a diasporic city where traditional Jews and secular Jews all rubbed up against one another, close-knit and uneasy, and New York. These cities and countries are different in ways too obvious to name. Nor am I suggesting that New York will go the way of Vilnius, or America of Europe. But consider the fact that when YIVO was founded as the intellectual (and spiritual) center of the Jewish diaspora, it was founded in Vilnius; when it needed to move because of World War II, it did so to New York City.

With roots in Europe—in capitals like Vilnius and in shtetlach across the continent—the New York Jew was a compote of Yiddish humor and biblically-inspired bookishness and amiable Talmudic belligerence and bundist progressive ideals (often lightly held) and a natural cosmopolitanism and a weltshmerz so deep it was a kind of decadence.

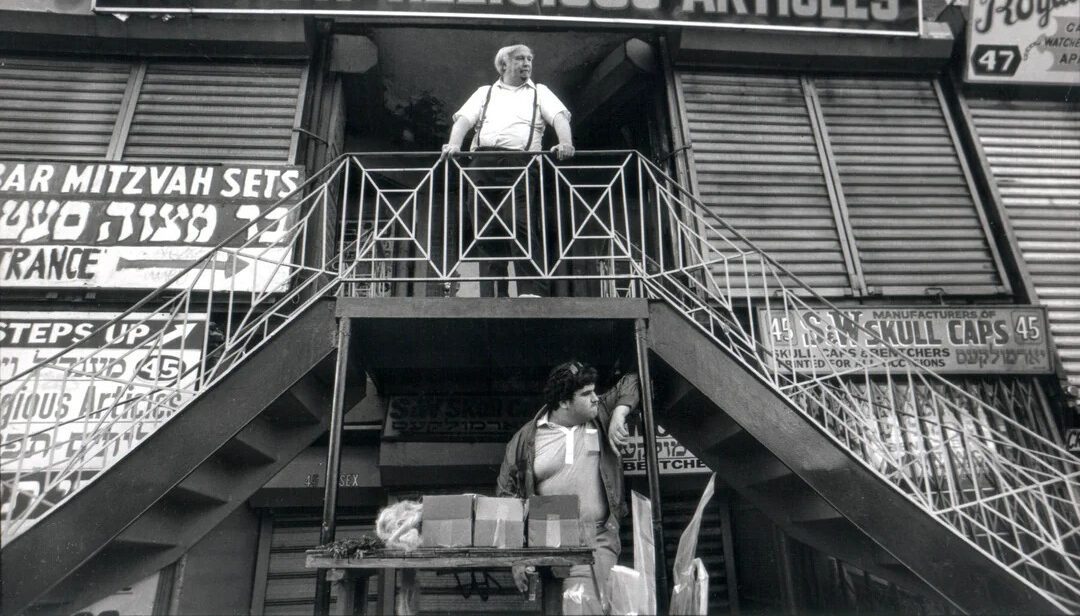

When I was born in 1987 in the Bronx—as a child of the “Golden Age” of American Judaism, as a teenager skipping classes at Yeshiva of Flatbush to read my way through Malamud and Bellow and Paley and Roth, as a college and then graduate student hoping to join the New York Jews’ brahmin class of the “New York Jewish Intellectual,” the idea of being a New York Jew was at once natural and ideal. Because to be a New York Jew was to have a homeland, and a community, and a literature, and a language, and an array of non-demanding and food-related traditions. It wasn’t without its insecurities and pretenses—a predictable politics, for instance, or a narcissistic self-centeredness—but it was simply the water, and it was simply mine. I felt as much at home in Borough Park, where my mother brought me and my sisters to buy yuntif clothes as a kid, as I did in Flatbush visiting my grandparents, as I did in the Village buying books with my father, as I did walking Central Park West with my friends, as I did sitting in the city’s relic-delicatessens. It was a sense of place that was the natural byproduct of a sense of history and security.

This self-conception was not private but communal, and not aspirational or performative but inherited. My mother’s parents fled Poland to find safety and then flourishing in this city—and flourishing, for their daughter, was a mix of Jewish and cultural and political commitments typical of her time and place: Lincoln Center and the left flank of the Democratic Party and a doctorate in literature; magazines with New York in the title (two of them, New York was too prust); Loehmann’s. My father, meanwhile, lived a different version of that same story: great-great-grandparents who fled Odessa for Brooklyn so that a century later my father could go to City College and then Columbia before raising a family in a room lined floor-to-ceiling with postwar American Jewish fiction and Marxist literary criticism and gilt-edged seforim. To be a New York Jew was an ethnic and cultural and religious identity, born of and bearing along a deep sense of belonging.

It was this very sense of belonging that YIVO had sought to cultivate in the early twentieth century—specifically in the context of a secular and diasporic nationalism that would unite Jews not around the Torah or rabbinical orthodoxies or geography (be it Palestine or Vilnius or New York) but around an inexpressible volkish essence. YIVO’s founders saw, in the shtetlach of Europe, the prerequisites of national identity: a language (Yiddish), a literature and culture (folkloric as well as rabbinical), and a history. All they needed was an understanding that they were not far-flung wanderers but in fact a great and powerful people.

Diasporic nationalism, as this movement came to be called, emerged in the early years of the twentieth century in opposition to the other prevalent ideologies and philosophies of the day. Zionists were elitists who would abandon Yiddish and folkish custom and culture for a Hebrew utopia in the desert; bundists were secular and assimilated Jews who prioritized “workers” while ignoring the plight of their own people. Diasporic nationalists alone were focused squarely on lifting up ordinary Jews in the places and ways they existed. It was a movement that didn’t require a revolution or relocation, but simply recognition: these Jews already belonged to something singular and sacred, Yiddishkeit.

All they needed was an understanding that they were not far-flung wanderers but in fact a great and powerful people.

YIVO was an expression of this hope. Launching their institute in Vilnius, a city where Jews represented forty percent of the population, the founders embodied an optimism about the Jewish Diaspora, a belief that Jews could feel at home in foreign lands. These were feelings I once had, too, living in New York City. What then to make of this story that started in Vilna in 1925, that bygone moment of diasporic optimism? Perhaps just this: that our moments of optimism are impermanent. Or bygone.

In Vilnius a century later, after the pogroms and purges and ghettoes and mass graves, I sit in the auditorium of the national library and listen to the Lithuanian scholars who, just after the fall of the Soviet Union and in the early years of Lithuanian independence, risked their careers and reputations to unearth the history of their country’s genocide—one perpetrated by their fathers and grandfathers against a vanished people.

One of these men, a historian named Egidijus Aleksandravičius, talks about the case he made that his countrymen had committed a genocide against their Jews—the historical evidence he discovered and presented, and the theories of genocide he deployed, in Lithuania’s early years of freedom from Soviet rule.

As he talks about his country’s genocide, and what it meant to write about and teach about that genocide, I can’t help but think—and I can see, in this man’s somber address, that he can’t help but think—of the debates taking place about Gaza.

In some ways, the question is an academic one. No more people get to eat or live because something is or is not labeled a genocide. But the stakes of the accusation are obvious. Since the Shoah, that high-water mark of state sanctioned mass murder, a country can commit no greater crime than a genocide. And if what is happening in Gaza is a genocide and Israel’s supporters are arguing it is not, then they have become complicit in this crime, which would constitute an especially terrible moral failure for Jews; and if this isn’t a genocide, and Israel’s critics keep wrongfully insisting that it is, then it’s an especially cruel attack against Jews that also constitutes a terrible moral failure. Israel’s supporters have put themselves or found themselves in one of two deeply unfavorable positions.

And what is the position of the New York Jew? I think back to the days and weeks following October 7, the images from Israel—the shaky cellphone footage of people fleeing a music festival, or of gunmen prowling quiet kibbutzim on a sunny day, searching for Jews. Of young and old women being paraded across the streets of Gaza. Of dead bodies inside bomb shelters and living rooms and bedrooms. There were the stories starting to come out—horrific and hard to believe, of babies cut from wombs, or infants knifed to death, or children tied together and lit aflame, of families murdered at their dining room tables as they sat down to celebrate the Jewish holiday.

And in the midst of trying to understand what was happening in Israel—what was true, how many were dead—something began happening in New York City. In the hours and days following the massacre, organizations and institutions that had been part of the New York Jewish world I’d known since I was a kid began to feel fragile, or even fearsome. At a rally in Times Square on October 8, people gathered to celebrate the attack, and one speaker boasted about the “rave or desert party where they were having a great time, until the resistance came in electrified hang gliders and took at least several dozen hipsters.” Attendees carried signs reading “DECOLONIZATION IS NOT A METAPHOR” and “BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY” and “GLOBALIZE THE INTIFADA.” On that day, it was obvious what these phrases meant.

Family and friends began exchanging news articles and social media links and rumors. Of student groups at Columbia or NYU or CUNY praising or justifying (the interpretive demands increased until they became untenable) the attack; of New York City cultural institutions and literary magazines publishing letters or articles ignoring or even celebrating what had happened while dismissing “smarmy moralizing about civilian deaths.” Of journalists tweeting about the “glory” of October 7, or of prominent progressives arguing that Jewish grief was not worth acknowledging. All this while the bodies were still being discovered in Israel; all this before a single bomb had been dropped on Gaza. So that by October 8, the city’s little magazines, and its humanities departments, and its progressive coalitions—places that had long felt like home—did not feel that way any longer.

On October 9, I was sitting in a café in Brooklyn, where I live, reading the stories out of Israel and Gaza, and exchanging yet more messages with family and friends in a fog of fear and horror. And I remember looking around the coffee shop at the New Yorkers on their laptops and phones and feeling with acute clarity that these were not my people—that, as a New York Jew, I didn’t feel especially comfortable in New York.

I’d find solace among Jews, then, where communal grief and fear would at least be allowed. But also on October 9, I read about the Israeli government’s decision to blockade food and water and medicine and electricity from entering the enclave, and I saw, in those same chats and email threads with family and friends, a brutality I didn’t recognize. And to ask questions about what was just, or what was prudent, was to side with them, those people who explained away the attacks as necessary or inevitable or deserved. And in the days and weeks that followed, as many of the people I know supported or justified (or stood shoulder-to-shoulder with people who supported or justified) a barbarous attack against Jews in Israel, and as many of the people I know supported or justified (or stood shoulder-to-shoulder with people who supported or justified) a barbarous form of collective punishment, I cracked in half.

And cracked I remained as the stories flooded from Gaza, and the images, and cracked I remained as the attack on Israel became a thing of contested history. There were no babies cut from wombs, it turned out, nor children tied together and lit on fire, nor rapes on the scale described on the day the attack unfolded. The children were merely murdered by guns and knives, the families merely shot to death in their homes. There were weeks of argument about just how many rapes and gang-rapes had taken place, and why some organizations had claimed to see things that hadn’t happened, and why some people were so intent on arguing that sexual assault had not happened when it had, and it was difficult, for a person cracked in two, to make much sense of this. At some point we stopped trying.

My last night in the dead capital was the Lithuanian holiday of Joninės, a celebration of the summer solstice, when the sun sets just before midnight, and the sky remains bruise-blue until dawn.

Vilnius celebrates its solstice by filling the city’s churchyards and public squares and lush green parks with concerts. It was something of an extraordinary sendoff—to walk the lamplit streets and rolling hills as string quartets faded to techno faded to folk songs, every block a music box.

I thought, for much of the night, about my grandfather, who was born in Poland in 1921, and who was set to study in one of Europe’s great yeshivas when the war broke out, and who led a Pesach seder from memory in Bergen-Belsen, and who lost his parents and seven siblings before building a new life in Brooklyn, where he liked to walk, with my grandmother, the broad boulevard of Ocean Parkway, that most mediocre of thoroughfares. Had he ever wandered beautiful, old streets like these, on beautiful blue nights like this one, with his mind reeling? Had he ever walked the streets of Brooklyn cracked in two?

I was thinking about my grandfather still the following morning at the Green House, a local Holocaust museum. Operating out of what had been a residential home on a side street of the city, the Green House lacks the well-funded polish of most Holocaust museums, but was more moving because of it, the work of memory here presented not as spectacle to be received but as a horrible archive arranged against forgetting. Just a few small rooms and an attic, all the walls crowded with photos and placards dense with text, the museum tells the story of Lithuania’s Jews during World War II, from the Soviet occupation to the Nazi occupation to the ghettoes to the mass graves.

It was in a photograph from the Vilna Ghetto that I saw him: a young man who looked like my grandfather. The same wide and lidded eyes (like mine), the same seriousness. It wasn’t him, I knew—my grandfather had not been in Vilna during the war—but he was the right age, and the resemblance was enough to make me pause. This man was sitting curled against a city wall, frail and forlorn, with an empty wicker basket beside him. Bread Seller in the Vilna Ghetto, the card read (or something like this). There were two or three loaves in the basket, no more. Another placard explained that food shortages in the ghetto were so severe, and inflation so high, that starvation was commonplace. And as I read this, and studied this grainy photo, and looked around that room of corpses and graves, I grasped it clearly: the people to whom this happened can never allow themselves to be weak; the people to whom this happened can never let another people starve.

Back home in the dying capital, New Yorkers went to vote in the Democratic primary for mayor. In my progressive pocket of Jewish Brooklyn, where millennia-old questions of religious practice or theological conviction are handled with empathy and openness, the city’s mayoral race had become a third rail. Andrew Cuomo’s supporters accused Zohran Mamdani’s of endangering the city’s Jews, and Mamdani’s accused Cuomo’s of endangering the city’s most vulnerable. A typically staid community listserv broke out in discord when one person mentioned canvassing for Cuomo, and then even greater discord when another promoted a Shabbat service in support of Mamdani.

On one level, this is a sign of flourishing—that we can disagree with one another, even intensely, but remain in community. But it feels less now like disagreement than dissolution. In the Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods I see signs supporting Cuomo; most everywhere else are signs supporting Zohran. It’s as if the New York Jew has been rent apart completely.

Much of this has to do with safety. Even in the post-October 7 fog, it is obvious that Jews in New York are not as safe as they used to be, and that they do not feel as safe. This precarity ranges in degree and kind, from the university students who must now be the right kind of Jews (secular, antizionist) to feel comfortable in certain spaces on campus, to the record-breaking tally of attacks on Jews in New York City since October 7—a tally which includes threats against synagogues and Jewish schools, assaults of Jewish children and families in more religious neighborhoods in Brooklyn, and dozens of incidents in which Orthodox Jews were spat upon or shouted at while going about their everyday lives. Jews have had their hats or yarmulkas knocked from their heads, or their sheitels pulled off; Jews walking down the street with shopping bags or strollers have been instructed to go back to Poland or free Palestine. Is there such a thing as a New York Jew when Jews no longer feel safe in New York City?

In the months since the primary, this feeling of precarity has only increased, and Mamdani’s win will likely make things worse. The city’s mayor-elect rode into office on a coalition that feels, at a minimum, inhospitable to many New York Jews. There are, of course, some New York Jews who voted for Mamdani, and who see their coreligionists’ attacks against him as grounded in either a conflation of antizionism with antisemitism or in Islamophobia, and there are certainly people opposing Mamdani who are guilty of both of these things. But it is also obvious that Mamdani’s progressive coalition is very different from progressive New York coalitions that emerged in the golden age of the New York Jew. Consider, for instance, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). At the time of its founding in the mid-1970s, the DSA was broadly supportive of Israel, with Michael Harrington arguing that it was preposterous to equate Zionism with racism. A half-century later, in a September 2023 speech at the DSA’s annual conference, Mamdani told the crowd that “we have to make clear that when the boot of the NYPD is on your neck, it’s been laced by the IDF.” One can attribute this shifting attitude towards Israel—and toward conspiratorial language situating Israel at the center of global villainy—to any number of things, but what seems obvious to me is that no New York Jews of yore were sitting in the room when Mamdani said that. At least none that he felt afraid of offending.

The solution that has been proposed to combat this sense of insecurity—Trump’s war on “antisemitism”—did not stop that coalition from finding electoral success, and has only empowered the state’s ability to censor its citizens, while emboldening antisemitism on the right. MAGA has now mainstreamed men like Nick Fuentes and Tucker Carlson, who talk openly about the outsized influence of the Jews—comments that were met with a spirited defense of Carlson by the Heritage Foundation, and silence from JD Vance, the movement’s heir apparent.

This is the national crackup that reflects the New York Jew’s crackup that reflects my own. We are presented with impossible options, and pyrrhic solutions, and lost allies on all sides.

In the midst of this crack up, I kept on waiting for someone to come and explain it. Someone who might describe what it means to be a New York Jew alienated from his native homeland of New York City and his ancestral homeland of Israel. Someone who might put to words what it means to be a New York Jew just as the concept passes into obsolescence. But such an explanation never came. This, perhaps, is the surest sign yet that something has come to an end—that in such a time as this, my people were nowhere to be found.