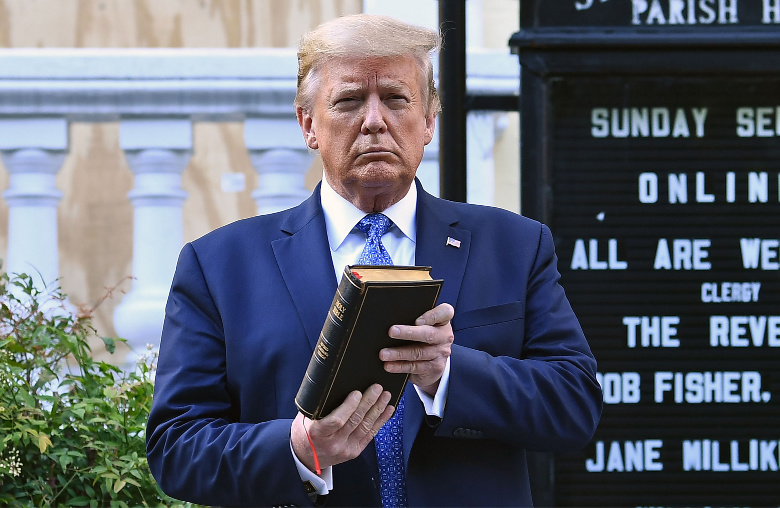

On June 1, 2020, within the space of 48 minutes, Washington’s Lafayette Square went from being a peaceful protest site to a presidential photo opportunity. In between those two realities, police forcibly removed demonstrators who had assembled across from the White House to protest against police brutality and systemic anti-black racism. Rubber bullets, smoke grenades, and tear gas rained down on demonstrators as President Donald Trump spoke in the Rose Garden. He then proceeded to walk through the now-cleared square to St. John’s Episcopal Church to pose with a Bible for news cameras. In the week since, there has been fierce debate about what it all means.

Many have mocked the photographs of the president at the church, pointing to Trump’s awkward posture and seeming unfamiliarity with the sacred text. (Late-night talk show host James Corden even provided a tutorial on proper Bible-holding.). Others, including some white evangelical leaders, have celebrated it as a faithful demonstration of reverence for a church that had been damaged during protests. And still others, like Bishop Mariann Budde of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, have decried the event as a “stunt” that conscripted religious symbols and spaces into a brazen political power move. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden also joined in admonishing the pageantry of the event, both emphasizing that Trump held a Bible but did not read from it and did not speak from it. And on June 2, the American Bible Society issued a statement, declaring “we should be careful not to use the Bible as a political symbol, one more prop in a noisy news cycle.”

The substance and symbolism of the Bible cut across much of the coverage. But something else was going on that day that seems to have been overlooked by most commentators, hiding in plain sight. The president did not just stand in front of a church with a Bible. He stood in front of a church with a Bible for the camera. Americans have been socialized for generations not to see the political, social, and cultural power of photography, even as we have become so intimately habituated to the visual worlds they produce. That is, on some level we know that photographs have been used to polish, persuade, coerce, and deceive but still we so often trust them to put us at the scene, on the ground, as an eyewitness to history. That is the allure and the damning power of the photograph. A picture can never be reduced to a thousand words.

What is more, since its origins in the 1930s, the industry of American photojournalism has always been part of the power grid of race and religion, electrifying them through its images. President Trump, an expert at publicity, is no stranger to using photographs for his own ends. Looking outside the frame of him at St. John’s, and listening attentively to the cacophony of camera shutters recorded by video footage of the event, we should take the genre of “photo op” seriously as a mechanism of power. In doing so, we can better approach photojournalism, in particular, as a central feature of modern American political discourse. And we also open ourselves to seeing American religion, including the power structures of American Christianity, not only as subjects that have been represented in photography, but as subjects that have been produced through photographic practices. To be seduced by debates about what the photographs are of, in short, is to risk missing the much deeper entanglement of photojournalism, race, and religion.

What American photojournalism is and should be has been contested from the industry’s beginnings. Broadly speaking, photojournalism developed out of various threads of photographic practice, including war correspondence during the Spanish American War, urban reform movements, street photography, transformations in art photography, and even the Kodak culture of the turn of the twentieth century. Although many of these threads date to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was not until the 1930s that photojournalism as we know it began to take shape. The camera’s presumed power to simultaneously record events and reveal underlying truths contributed to the success of these early efforts. It also made way for abuses, invasions, and violence, particularly around religion and race.

Magazines like Time, Fortune, and Life, which began publishing in the 1920s and 1930s, were among the first to employ staff photographers in an effort to shape public opinion primarily through the power of photographs. All three were started by publisher Henry R. Luce, a child of Presbyterian missionaries to China who folded a version of Protestant triumphalism into his publishing which, in turn, gave shape to the visual regimes of what he famously called “the American Century.” (Significantly, his wife Clare Booth Luce is also credited with the original idea for Life, although she was eventually shut out of running the publication.) One of the first staff photographers Luce hired, Margaret Bourke-White, was widely celebrated for her aesthetic and reporting skill, and often focused her lens on religious figures, places, and events alongside an extensive catalogue of other subjects. But her own description of her early work with African American religious communities in the American South drips with racist sensationalism of “religious frenzy” that “seemed close to some tribal ritual, as though the worshippers still answered to the rhythm of the jungle.” Racial violence has been part of photographic reporting of religion since the beginning.

At the same time, during the economic and political crises of the 1930s, the federal government employed more than a dozen photographers to document American life as part of federal relief efforts. The visual record of this decade brought the techniques of social and street photography, which had been instrumental to reform efforts since the late nineteenth century, into the bureaucracies of the American state. Shooting scripts for these photographers, who were mostly white and male, frequently ignored the context of racial violence, and the further harm that their lenses could inflict, and their images of black Americans were too often staged and sanitized. Religion, too, in this archive is often bluntly used to either document poor conditions or decipher American grit, often both at the same time.

In the years after WWII, the National Press Photographers Association was organized to provide professional guidance and a standardized code of ethics for visual journalists, but black photographers still struggled to find venues to publish their work. In the early 1950s, Roy DeCarava won a Guggenheim Fellowship to photograph life in Harlem, where he had lived almost his entire life. He wanted to provide a visual record of this place and its people that white photographers missed, no matter how well-intentioned they may have been. His prints are a stunning exploration of the spiritual registers of daily life in Harlem, and by the time he died in 2009, he was considered “one of the most important photographers of his generation.” But at first, no one would publish his work. It was not until 1955, after he had collaborated with Langston Hughes on a book, that Simon & Schuster published his photographs to accompany Hughes’s text in The Sweet Flypaper of Life.

That same year, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened its Family of Man exhibit, which included both the work of DeCarava and Bourke-White. It was a collection of more than 500 photographs from around the world, woven into a visual counternarrative to Cold War nationalisms. The exhibit organized pieces by photojournalists, amateurs, and other professional photographers into sections captioned by quotes of wisdom from various religious, spiritual, and ethical traditions—from Plato to Daoism, Navajo verses to Hebrew Bible texts, Albert Einstein’s quotes to snippets of a “Baronga-African Folk Tale.” It was an ambitious endeavor and an important touchstone of postwar American society and culture. Nevertheless, this exhibit, too, fell into pitfalls of representing religion and race, and it went back and forth between sensationalizing and sanitizing these complex features of American life.

Although we can no longer stand in the gallery and behold the exhibit, we can flip through the exhibit catalogue. In the pages corresponding to the exhibit’s “Religious Expression” section, there are fourteen images that portray religious practices and traditions from across the world to a primarily American audience. The two images of religion in the United States are of a black preacher and a black family sitting around a table reading what appears to be a Bible. American religion is represented through African American forms, without any consideration of the violence exacted on black bodies in the name of religion or the conditions in which black religious traditions were formed and practiced. The exhibit appropriated very real differences across traditions, differences grounded in the violence of colonialism, enslavement, and economic circumstance no less than differences of theology or creed, to tell a story of humanity triumphant. That Family of Man could at once display photographs by people of color and women, display photographs of people from around the world of various races and religious traditions, and still be shaped by (and reproduce) systems of racism demonstrates how important it is to scrutinize photography’s role in forming how race and religion become visual markers of American citizenship.

The political, technological, demographic, legal, and cultural landscapes of the United States have undeniably changed in the century since the birth of modern photojournalism. And without a doubt, there are innumerable confluences of religion and race in the history of photojournalism, from overt white supremacy to tacit racist coding to deliberate tactics of liberation. My point is not to name a single story of religion and race within this history but rather to identify their power within photographic practices. Indeed, if anything, over the past century photographs have become even more central to American public life and culture. Digital media have breathed new life into visual technologies and visual modes of communication, dramatically increasing the ability to produce and to access images of events as they unfold.

President Trump seems to instinctively understand the power of digital media and photography. He is, after all, a reality television star and a veteran cover subject for tabloids. Even from his first day in office, he was debating—and doctoring—photographs that showed the size of his inauguration crowds. In the past, he has fixated on his (real and fake) covers for the Luce-founded Time magazine. That he staged a photo op at St. John’s Church amid protests should perhaps be no surprise, even if the brutal methods to get there were. Not long after his appearance, the White House tweeted a 29-second edited video of the events, minus the removal of protesters. Set to soaring music, it begins with a shot of the White House and then transitions to Donald Trump walking off the grounds, leading a group of white officials (all of them unmasked, despite the ongoing coronavirus pandemic). After a few seconds of Trump standing in front of the boarded-up church with the Bible, the footage cuts to him returning to the White House, through lines of law enforcement in full riot gear, and concludes with a long shot of the executive residence, its roof dotted with Secret Service and the Washington Monument towering in the background.

This moment, as others before, compels accountability for systemic anti-black racism that the nation’s special solicitude of whiteness has harbored since its founding. The president’s photo op at St. John’s may very well have been a pageantry of deflection. It may have been a page from his reality TV script. It may foreshadow more pernicious anti-democratic tendencies. Whatever the case, the work of racial justice requires far more than careful scrutiny of pictures. But for however long we catch ourselves looking at these pictures, we would do well to attend to the ways in which photographs are matrices of power. They are cultural artifacts caught up in histories, and in contexts of race, gender, sexuality, class, and religion. By taking the cameras at St. John’s seriously, by looking beyond the Bible on display and the symbolism it invokes, we are better prepared to understand just how deeply visual productions of religion and race have been ingrained in American life and culture.

Rachel McBride Lindsey is assistant professor of American religion and culture at Saint Louis University and co-director of Lived Religion in the Digital Age. She is author of A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America and is currently working on a book about religion, race, and photojournalism in the twentieth century.