Beth Moore is still making waves. On April 7, soon after announcing her departure from the Southern Baptist Convention, she took to Twitter to proclaim complementarianism “a doctrine of MAN” and to beg forgiveness for supporting the theology of male headship. “I could not see it for what it was until 2016,” she wrote. (Moore later clarified that she hasn’t totally abandoned complementarianism; rather, she disapproves of how the doctrine became supreme.)

Conservative evangelicals were swift to rebuke her, quoting scriptural commands for women to “remain quiet” and expressing regret that Moore was “running to embrace the world.” Others applauded her for acknowledging how complementarianism is derived from human culture, not divine law. The latter critique is also described in a recent wave of academic books that argues that complementarianism and its corollaries—”purity culture” and “family values”—are based on a foundation of sexism and white supremacy. Within this wave is Beth Allison Barr’s Making Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth, which examines how figures like James Dobson “sanctified” the nineteenth-century “cult of domesticity” demanding women’s piety, purity, submission, and domesticity.

There is another, lesser known source of inspiration for modern white evangelicals and Dobson, in particular: eugenics. And this specific history helps to explain how procreative, heterosexual marriage became enshrined as the single-most important moral duty for some evangelicals—one that believers are enticed to pursue from a young age and then to perform at all costs, including physical and psychological harm.

Eugenics, a program to improve the “quality” of the human population, gained popularity in the early twentieth century, when more than 30 states enacted laws authorizing the forced sterilization of the “unfit”—poor, disabled, immigrant, and otherwise socially undesirable persons. Eugenics and evangelicalism have long been thought to be antithetical, as evangelicals largely opposed sterilization. (As Christine Rosen explains in Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement, evangelicals were not inclined to support any practice that grew out of bogeyman Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory, nor were they as enthusiastic about social reform as were the liberal Protestants who endorsed eugenics—their focus was on saving souls.) But the evangelicals-versus-eugenics framing is too simple. Evangelicals fervently supported other eugenics programs, including anti-miscegenation laws, stringent immigration restrictions, and even so-called “responsible breeding.” The Rev. Billy Sunday once ranted about the last at a 1917 revival, citing the famous case studies of the “Juke” and “Edwards” families to stress the impact of heredity. (Eugenicists claimed the pseudonymous Jukes were a long line of criminal degenerates, while the descendants of the revivalist preacher Jonathan Edwards were virtuous and well-bred.) A New York Times writer marveled that “the scientific aspect of his sermon … overshadowed the denunciations of sin.” Sunday, after all, had a reputation for rebuffing modern science.

Evangelicals even more firmly embraced eugenics after World War II, as sterilization advocates shifted focus to the other side of the eugenics coin: “positive eugenics.” Positive eugenics aimed to increase the breeding of the “fit” (able-bodied, middle-class whites), providing a far more respectable face for the movement, which had become imperiled by scientific criticism and the rise of the unpopular Nazi party. This modernized form of eugenics gelled with racist notions of Christian dominion, which avowed segregationist and eugenicist R.J. Rushdoony would popularize in the 1960s and 70s.

One positive eugenicist who particularly shaped religious conservatives was Californian Paul Popenoe, a central figure in my recent book, The Unfit Heiress: The Tragic Life and Scandalous Sterilization of Ann Cooper Hewitt. Popenoe had been one of the most prolific advocates for the segregation and forced sterilization of people whom he deemed to be “waste humanity,” even inspiring leaders of the Third Reich before the time came for him to rebrand as a defender of patriarchal, procreative marriage. In 1930, Popenoe, an atheist, opened the American Institute of Family Relations (AIFR) in Los Angeles to improve marital harmony and remove what he thought to be obstacles to white reproduction, such as rape, masturbation, pornography, female frigidity, and feminist yearnings. Over the next several decades, Popenoe counseled white couples on the importance of strict gender-norms and same-race marriage, training psychologists, clergymen (many Baptist and Mormon), and youth group leaders—his new allies in the racial betterment project—to do the same. According to Hilde Løvdal Stephens, author of Family Matters: James Dobson and Focus on the Family’s Crusade for the Christian Home, he instructed counselors to use “heredity” and “interpersonal compatibility” as codes for race, especially when his views on race began to go out of vogue.

Popenoe encouraged women to make themselves sexy for their husbands, let domestic violence slide, and look out for their man’s ego and sexual needs. Knowing that some women were sexually reticent, he hired Dr. Arnold Kegel to develop a treatment. (“Kegels” were born.) Popenoe explored methods to suppress homosexual desire, such as electroshock therapy, though it’s not clear if his institute ever used this technology. The man dubbed “Mr. Marriage” also gave considerable attention to clients’ temperaments. One of his first-generation eugenics colleagues, Roswell Johnson, abetted these efforts. Johnson, who’d previously crafted intelligence tests to identify and weed out the “feebleminded,” developed an extensive personality test for assessing compatibility, an adaptation of which is popularly used by Christian marriage experts today.

Popenoe expanded his reach when he began to author a column based on real-life clients for Ladies’ Home Journal and make television appearances. He hosted the syndicated Divorce Hearing and was a regular guest on the conservative evangelical and right-wing media mogul Art Linkletter’s House Party on CBS. Before his death in 1979, he helped give rise to a cottage industry of Christian sex and marriage guides, including Herbert Miles’ 1967 Sexual Happiness in Marriage; J. Allan Peterson’s anthology The Marriage Affair, which put Popenoe’s patriarchal marital ideals alongside those of Billy Graham and Tim LaHaye; and Tim and Beverly LaHaye’s 1976 The Act of Marriage: The Beauty of Sexual Love. (All of these books cited the eugenicist.)

Beyond pushing run-of-the-mill gender essentialism and the constant, careful management of women’s bodies and personalities, Christian marriage manuals helped normalize marital misery—a phenomenon well captured by another of LaHaye’s titles, How to Be Happy Though Married. They often portrayed marriage as groan-worthy, but “worth it,” laying the groundwork for Gary Chapman’s 1992 Five Love Languages, which has become a perennial bestseller. In The Tragedy of Heterosexuality, scholar Jane Ward notes that books like Chapman’s foreshadowed more contemporary Christian mega-church events, which similarly ask individuals, particularly women, to reinvent themselves for the sake of lifelong unity. (One can’t help but also think of the recently gone-viral video of a Baptist pastor who berated wives for “letting themselves go.”)

Of course, adapting eugenicists’ notions of hygienic and well-adjusted marriage isn’t inherently racist; and as Ward notes, secular culture, too, drew upon positive eugenics. Mid-century television programs like I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners made comedy of marital discontent, while ads stressed the importance of maintaining trim figures, skin bleaching, douching, and even modifying one’s demeanor, where necessary. But the eugenicist-evangelical alliance manifested in a present culture that idealizes white reproduction, stokes fear of non-white reproduction, and blames a lack of marital morality for problems actually wrought by sexism and white supremacy.

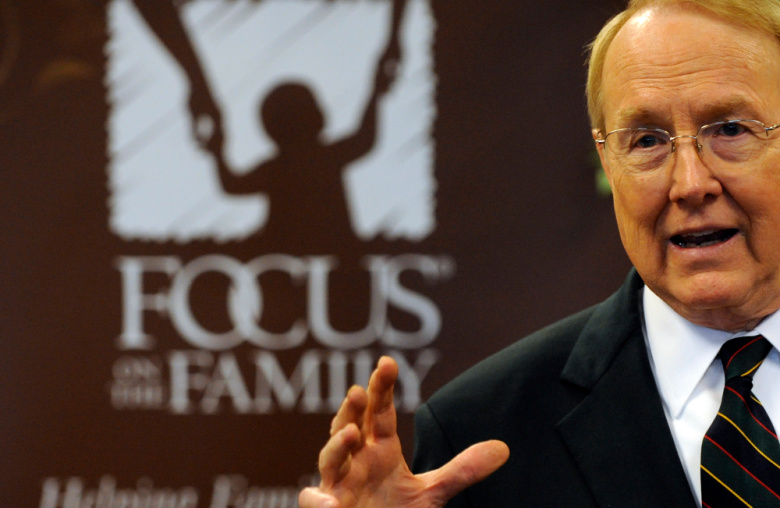

This phenomenon may be best illustrated by the tracing the trajectory of psychologist James Dobson, author of many child-rearing and marriage manuals; founder of the hugely influential para-church organization Focus on the Family (FoF); and former host of the so-named radio program. FoF was formed in 1977 to promote the same ideals as AIFR—heterosexual marriage and conservative gender norms—in addition to creationism, school prayer, and other culture war imperatives.

Prior to launching his pro-marriage empire, Dobson went to work for Popenoe—a detail conspicuously missing from journalist Dale Buss’s authorized biography of him. As the eugenicist’s assistant, he authored numerous publications on male/female differences and the dangers of feminism. Like his mentor Popenoe, who wrote the forward to his first book, Dobson viewed homosexuality and feminism as grave threats to the family, seeming to rank crises like domestic abuse much lower. (In his 1983 Love Must Be Tough, he even questioned the innocence of abuse victims, recalling a woman at his church who supposedly baited her husband to hit her so she’d have a bruise to show off to the congregation.)

Post-AIFR, Dobson’s extensive output for mostly white audiences was sprinkled with expressions of anxiety about interracial marriage and non-white reproductive trends, as Popenoe’s had been. Whereas Popenoe advised “marrying your own,” FoF discouraged crossing the color line, claiming concerns about compatibility. And whereas Popenoe fretted about the prolific reproduction of the lower classes, particularly Mexican Americans in California, FoF devoted much attention in the 90s and early 2000s to Black welfare dependency and out-of-wedlock births. Now-FoF President Jim Daly even invoked the infamous Moynihan Report, which suggested that the welfare state had contributed to the disintegration of the Black family in impoverished areas. In a copublication of Political Research Associates and the Women of Color Resource Center, political scientist Jane Hardistry has noted that by carefully avoiding overt statements of the inferiority of people of color, organizations like FoF managed to spread the idea that African Americans constituted the bulk of welfare recipients (they do not); obscure racial and gender discrimination as causes of poverty; and tout white Christian norms as the solution to any and all social ills.

Dobson, who retired from FoF in 2009 and now hosts the radio program Dr. James Dobson’s Family Talk, has repeatedly betrayed his personal anxieties about a dark-skinned takeover. After visiting the southern border in 2019 at the Trump administration’s invitation, he claimed to fear “illiterate,” “unhealthy,” “violent criminals” would “bankrupt” and “take down” America, if not controlled. Popenoe’s protégé has also coupled comments about immigration with myths of declining birth rates in America, as have Christian-right activists behind a slew of books and films predicting the end of white civilization. (It may have been Ben Wattenberg’s blatantly eugenicist 1987 book The Birth Dearth: What Happens When People in Free Countries Don’t Have Enough Bodies that first popularized such notions of cultural and genetic suicide; Ward notes that this text explicitly influenced the political rhetoric of 90s conservatives like Pat Robertson, Pat Buchanan, and Dan Quayle.) Dobson often appeals to his opposition to abortion as some sort of proof of his anti-racism. But in framing abortion as Black genocide, he once again infantilizes women of color by pretending they have no agency.

The interplay between secular eugenicists and religious conservatives utterly contradicts the latter’s claims to reject godless culture, which may be why Popenoe’s son thought the allyship between his father and people like Dobson so curious. Reflecting on his parent’s later years in a publication of the secular think-tank Institute of American Values, David Popenoe remarked, “My father was no more religious than ever, but [religious persons] were his new professional and ideological allies and protegees.” But beyond this revealing secular-religious collaboration, such history reveals how fears of racial decay have shaped the conservative imagination of morality. Eugenicist fears of white replacement have rendered marriage non-negotiable, even in cases where marriage requires, in Ward’s words, “a significant amount of performativity.” African Americans who veer off-script are blamed for any social and economic hardships they may experience; and whites who do so are also dehumanized.

The Popenoe-Dobson legacy still reverberates loudly within corners of white evangelical culture, where sexual abuse is still rampant and married women face pressure to quietly endure because of the stigma of divorce. Some married women are shamed for not wanting to have a “quiverfull” of children, especially in circles where ideas of white decline pervade everyday conversation. In some cases, teens and young adults are threatened with disease and lifelong sexual frustration if they do not “save” themselves for heterosexual marriage, which is sold as the be-all, end-all of earthly life. The “abstinence-only” message, rooted as much in fears of race-mixing as STDs, teaches that girls are either pure or utterly wanton—there is no in-between. Some gay evangelical youth and college students are still subjected to conversion therapy, which many medical professional associations have deemed ineffective and harmful.

Under the mantle of outbreeding “inferior” people, these conservative messages and mores have sanctioned many harms. Beth Moore is right to look around and note that much of what passes for God’s plan today is devastatingly “of man.” In the case of complementarianism and family values, evangelicals have taken up a fight with humanity’s worst designs.

Audrey Clare Farley is a historian of twentieth century American fiction and culture. She holds a PhD in English literature and is the author of The Unfit Heiress: The Tragic Life and Scandalous Sterilization of Ann Cooper Hewitt. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Republic, The Washington Post, and many other outlets. Follow her @AudreyCFarley.