JD Vance met Peter Thiel in 2011, when Thiel gave a speech at Yale Law School. Vance had moved up from Ohio State to Yale, rocketing through the American elite. Thiel was a former lawyer turned venture capitalist turned Silicon Valley mogul. At the time, as Vance puts it, Thiel was “hardly a household name,” but he already had a notable career. Thiel was the founder of PayPal, and the “don” of what Fortune journalist Jeffrey M. O’Brien called “the PayPal Mafia,” the network of PayPal employees who would go on to become major players in Silicon Valley and beyond.

Thiel was of the world of Silicon Valley, but in some ways not a part of it. Since his days as an undergraduate at Stanford, where he founded the conservative newspaper The Stanford Review, Thiel had been an entrepreneur of the heterodox and the contrarian. After a short stint as a securities lawyer, he had gone into finance and then Big Tech, building or investing in some of the most notable companies in the Valley—including Facebook—but also keeping his distance from what he took to be the Valley’s conformist brand of liberalism.

Thiel’s 2011 talk argued that elites at places like Yale Law School were far too focused on competing with their peers, mindlessly moving up the ladder of prestige. Graduates did not focus enough on creating anything of real or lasting value. And, as Vance wrote in a 2020 blog post on The Lamp, Thiel connected the problem of “elite professionals trapped in hyper-competitive jobs” with a broader technological and economic stagnation, born of an inability or unwillingness to use technology to make life better. Thiel counselled avoiding competition and focusing instead on creating (and capturing) real value where others were not thinking to compete.

Vance writes that he had an “obsession with achievement” that was born, in part, out of a profound conformity of thought. He wanted to rise through the ranks at elite institutions not to achieve anything meaningful but rather to win an empty “social competition.” Thiel’s argument thus struck a chord with Vance, launching him on a journey that, among other stops, included an embrace of Catholicism in place of his natal Protestantism.

It is clear why there would be a resonance between Vance and Thiel. Thiel too tells his story as a story of being failed by established meritocratic structures. His message to Vance’s law school class might well have been advice to his younger hypercompetitive self: don’t buy into the values of your peers and the wider world around you. They want you to be a senior partner at a law firm, but you’ll never go from Zero to One (in the words of Thiel’s 2014 business book) if you follow the herd.

Vance and Thiel became friends. Thiel blurbed Vance’s bestselling 2016 memoir, Hillbilly Elegy. Vance spent two years working for Thiel’s venture capital firm, Mithril Capital. With Thiel’s backing, Vance would co-found Narya Capital. Narya focused on supporting companies in the Rust Belt communities Vance wrote about in his memoir, but also more generally opposing what it saw as the political limitations and biases of the Valley’s “Big Tech oligarchy.” Among other companies, Narya has invested in Rumble, the conservative video-sharing platform, which Thiel also invested in. Additionally, Thiel contributed generously to Vance’s political career. In 2022, Vance ran for Senate in Ohio, renouncing his prior criticisms of Trump and the MAGA movement. Thiel contributed $15 million to a super PAC supporting Vance’s run.

One might momentarily mistake Thiel’s critique of meritocracy as a critique from the left, but it is rather a critique of neoliberalism from the far right. Thiel has come to be skeptical of democracy, and he has been heavily involved in promoting the career and the ideas of the neo-reactionary blogger Curtis Yarvin, who argues that monarchy is superior to democracy. Vance too has expressed admiration for Yarvin and his attacks on what Yarvin calls the “Cathedral”—or, as it is called elsewhere, the Deep State—that is, the permanent bureaucracy that comprises the federal government, and its liberal enablers in academia and journalism. In this way, both Thiel and Vance are part of what has been called the post-liberal right. Like Yarvin, they advocate for “RAGE”—Retire All Government Employees—as part of what Yarvin calls a “hard reset” or “reboot” of American society.

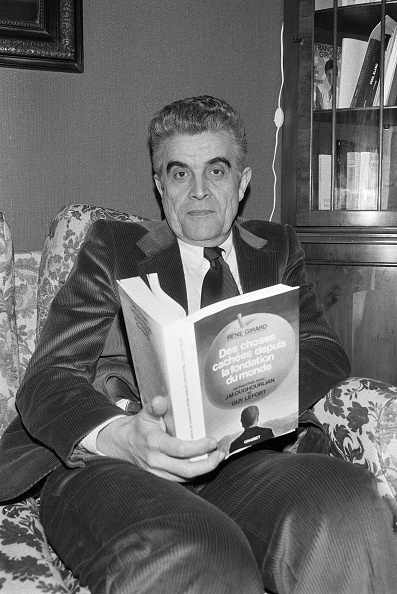

Much has already been written about Thiel and Vance’s connections to neo-reactionary thought—and these are alarming indeed—but the most important intellectual bond between Vance and Thiel is not directly political, although it also may have alarming political consequences. In addition to helping him transition into the world of post-liberal neo-reaction, Thiel crucially introduced Vance to the work of the philosopher and literary critic René Girard. It is in Girard’s thought—his account of what he called mimetic theory and his description of the “scapegoating” mechanism—that we arguably see Thiel’s deepest influence on Vance. To understand Vance, who could soon be vice president to the oldest man ever to assume the presidency, we must understand Girard.

René Girard (1923-2015) was a French philosopher and literary critic, most famous for developing what he called “mimetic theory” and for his writing on sacred violence. Building a universal anthropology, albeit one with strongly Christian undertones, Girard argued that human desire was fundamentally mimetic. People desire what they see other people desire. And as they compete for the same scarce resources, violence spreads through the community. Violence becomes generalized and escalates in intensity and force. In order to quell this violence, a symbolic culprit must be found and eliminated from the community. This is how the scapegoat mechanism is born. The scapegoat mechanism allows a community to resolve its raging conflicts by channeling its violence onto a symbolic sacrifice and temporarily wiping the slate clean, according to Girard.

The original scapegoat appears in Leviticus 16 as part of the Yom Kippur ritual. One goat is sacrificed; the other is allowed to live and to carry away the sins of the Israelites from the tabernacle. But Girard thinks of the scapegoat mechanism as universal. All religious societies channel rivalry and violence, born of mimetic desire, into the sacrifice of this or that scapegoat. Of course, sacrificing the scapegoat doesn’t quell violence for long, and the cycle must begin anew. Yet Christianity represents something new for Girard in the history of the scapegoat, in that the Christian telling of the scapegoat myth recognizes that Christ is innocent, and not only innocent but all-powerful. The community sacrifices Christ, but the Christian comes to see that the scapegoat mechanism is fundamentally unjust.

Rather than construct a person who bears all the sins of the community, according to Girard, Christianity tells the story of someone who is both all-powerful and completely and perfectly innocent, and who is therefore the victim of his community. The scapegoat in Christianity is, it turns out, the wronged party, a holy victim. Moreover, the superior being, in the form of Christ, allows himself to be unjustly martyred, and in so doing reveals the injustice of the scapegoat process.

The death of Christ becomes an occasion for Christians to reorient their mimetic desire. Rather than mimicking other humans who are competing for the same resources, Christians strive now to mimic Christ and through Christ God. Thus, at least in theory, is the cycle of mimetic violence ended.

To understand Vance, who could soon be vice president to the oldest man ever to assume the presidency, we must understand Girard.

But the Christian story also had the paradoxical effect of desacralizing the scapegoat. Pre-Christian societies depended on myth as a means of covering up the violent excesses of mimetic desire. The community could tell itself that it had quelled the source of communal strife. But for Enlightenment thinkers, the scapegoat myth no longer had force. In this way, Christianity laid the foundations for aspects of the Enlightenment. But by rejecting God along with the scapegoat myth, the Enlightenment did nothing to quell or redirect mimetic desire. Instead, the old mechanisms of mimetic rivalry and envy persisted. Only now there was no way to satisfy the community. The war of all against one (the scapegoat) threatened again to become a (postmodern) Hobbesian war of all against all. This, anyway, is what Girard means when he writes that “atheism is a Christian invention.”

Girard’s ideas emerged from a long interdisciplinary tradition of anthropologically-oriented literary criticism. We find precursors in the writing of Freud (Totem and Taboo), Frazer (The Golden Bough), Durkheim, Nietzsche, and the French sociologist and criminologist Gabriel Tarde. There is a large and growing scholarly literature exploring all of these connections. And among scholars it is an open question whether Girard represents a break with these prior theories or something like their syncretic culmination or perfected form. Girard affirmed Frazer’s influence and denied Tarde’s.

Yet Girard has most come to be associated with these theories, in the academy and beyond, in no small part because of Thiel’s generous financial boosting. Thiel was introduced to Girard as an undergraduate at Stanford. He was so taken with Girard’s ideas that he founded Imitatio, an organization dedicated to developing and studying Girard’s mimetic theory. Thiel has since sponsored various conferences on Girardian thought, including the René Girard Lectures series. I have not found any solid estimate of how much Thiel has spent supporting and promoting Girardian thought, but with his funding for research grants, publications, educational programs, and other activities, it would not be unreasonable to imagine, as Scott Alan Lucas has written, that the figure is in the millions.

Thiel has also spoken and written many times about Girard’s profound influence on his thought, including at the NOVITATE Conference in 2023 at Catholic University. At that conference, Thiel gave a speech in which he claimed that we face two challenges: the Apocalypse, brought on by existential risk, and the Antichrist, represented by the rise of a totalitarian world-government. The solution to this conundrum for young people today is to “go to church,” an odd phrase considering that Thiel has elsewhere described himself as “religious but not spiritual” and seems not to belong to any specific denomination, though he describes himself as a Christian.

Girard was not explicitly a political writer—though he did write a supportive blurb of Thiel’s co-authored book, The Diversity Myth (1995)—but it is not hard to see why Girardian ideas might offer intellectual and spiritual succor for the aspiring post-liberal rightist. Girard presents a social critique of dominant institutions while escaping materialist explanations for the problems those institutions cause. In his schema, our problems arise not from exploitation or poverty but from a quirk of human desire—our fundamentally mimetic natures—and the solution is ultimately religious and Christian, subordinating our mimetic drive to the highest good: God, in Jesus Christ.

In 2004, Thiel sponsored a weeklong conference on the Apocalypse, and gave a talk there called “The Straussian Moment.” Later published in Politics and the Apocalypse (2007), the essay outlines Thiel’s views on the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. This essay is one of Thiel’s most striking and original political statements and shows some of what is at stake for him in Girard’s thought.

For Thiel, the terrorist attacks revealed a flaw in standard secular assumptions of liberal democracy. Faced with a undeterrable foe—a foe that has not forgotten the Schmidtian distinction between friend and enemy—the West has been forced to reconsider core tenants of its political theology (or rather, its belief that it can do without a political theology). John Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers had worked to eliminate fundamental ideological differences by forging what Thiel calls the “American compromise”—the notion that we might bracket fundamental questions of anthropology and theology. Locke constructed an intellectual framework that allowed the founders of the United States to retain the public form of Christianity, but to drain those forms of their animating spirit. What we humans are is fundamentally unknowable, but we could bracket the question of our natures and get on with the business of engaging in lucrative forms of trade and economic development.

But the terrorists who struck America on 9/11 had not forgotten these fundamental questions. They were not, Thiel claims, motivated by worldly concerns. They were instead fundamentally opposed to the ideals of the West. But their unwillingness to brook the American compromise led to thorny problems. If the U.S. fought this newly revealed foe with their own methods, it would become merely a mirror of their opponent, and their opponent would have won. Moreover, the West could not, by force of will, return to a time before it had bracketed fundamental differences and questions of human nature. The damage of the Enlightenment was, in a sense, irreversible. God would remain dead and buried.

Girard plays a pivotal role in helping Thiel arrive at this guardedly pessimistic conclusion. To be sure, Thiel finds hope in Girard’s account of the Christian inversion of the scapegoat story, in that like Girard he sees in the story of Christ the final mechanism that will control mimetic violence and bring peace. Yet in our postmodern world, by Thiel’s account, we have become all too aware of the mechanisms by which scapegoating happens. We have debunked the means by which we can channel and dissipate the community’s violence, but (outside of Christianity) we have not created a more peaceful world. Instead, mimetic desire might take on a new, more destructive form. Somehow, Christians must wait for the Second Coming without giving up on acting in the political sphere.

What is striking about Thiel’s essay is how it inverts Bush-era clichés about political Islam. Many pundits made a version of the claim that Islam had yet to undergo its version of the Reformation. Thiel, by contrast, in slightly obscured terms, seems almost wistful for the kind of faith and sense of seriousness that the American compromise had done away with. Nonetheless, one had to forge ahead, to find some new pragmatic balance between violence and peace, decided on a case-by-case basis. Keeping in mind that one day there will be a Second Coming, Thiel writes that the “Christian stateman or stateswoman” will need to find a thoughtful balance between “the limitless violence of runaway mimesis” and “the peace of the kingdom of God.” Though they “would be wise,” he cautions, “in every close case, to side with peace.” He wants to affirm Girard’s call for peace, but he also wants to make sure the national security apparatus has the Straussian means to quietly take the war to the enemy.

One can see how it is a short jump from this dour conclusion to some version of the quasi-fascist monarchism of Curtis Yarvin. The world is a corrupt dance of mimetic violence. The best we can hope for is a strong and wise CEO-like figure who might step in and manage the chaos, doing what needs to be done with quiet efficiency. This is not libertarianism or even neoliberalism in any traditional sense, but a kind of ideological techno-feudalism.

Beyond the specifics of political philosophy, Girard’s account of the inversion of the Christian story does different but related emotional work for Thiel and for Vance. It is hard to avoid noticing how much, in Thiel’s recounting of Girard’s thought, Christ comes to look like a libertarian entrepreneur. That is, Christ is an all-powerful individual victimized by the collective. He is a monopolist, with a corner on the market for virtue and goodness, an almost Randian hero who is victimized not despite the fact that he is good but precisely because he is good. And by destroying this miraculous scapegoat, the community doesn’t destroy him but affirms his divinity. Is it much of a stretch to imagine that Thiel sees in Christ a portrait of himself as a (job) creator?

Is that too glib an interpretation? I don’t think it is. Indeed, like the Promethean heroes of Atlas Shrugged, the Christ of Thiel’s reconstruction of Girard has all the charm of the adolescent power fantasies of the avid reader of Tolkien, Asimov, and Heinlein.

The best we can hope for is a strong and wise CEO-like figure who might step in and manage the chaos.

Vance also describes the appeal of Girard’s account of Christ, but the Christ story does slightly different emotional work for him. Vance is caught between a desire to hold his community to account and a reluctant recognition that the problems, born of deindustrialization, that he documents in Hillbilly Elegy and elsewhere, have social roots. It is a double game already evident in the uneasy ambivalence of his memoir, in which Vance extends sympathy to his grandparents while seeming unwilling to imagine that they very much resemble his mother, on whom he wants to heap blame. As Gabriel Winant bracingly writes in n+1, “what links Vance the memoirist and Vance the politician is a continuous (if escalating) policy of nearly absolute nonconfrontation with what made him who he is — the nature of the trauma that he pantomimes exploring in his book.”

In his 2020 account of his conversion to Catholicism, Vance explains the appeal of Girard’s thought. He writes,

I felt desperate for a worldview that understood our bad behavior as simultaneously social and individual, structural and moral; that recognized that we are products of our environment; that we have a responsibility to change that environment, but that we are still moral beings with individual duties; one that could speak against rising rates of divorce and addiction, not as sanitized conclusions about their negative social externalities, but with moral outrage.

Vance’s seeming confusion about whom to blame for the pathologies of his home community recalls the old agent-structure problem in sociology, in which scholars debate how to reconcile theories of social determination with the observation that we act as individual agents, as subjects. For Vance, too, these position form a neoliberal double-bind: liberals turn to government programs to solve the spiritual problems of a community, while conservatives put the burden on the individual alone.

It is Girard who gives Vance the intellectual machinery to overcome the contradiction, to find a post-liberal conservatism that transcends older orthodoxies. Reading Girard leads Vance to conclude, “In Christ, we see our efforts to shift blame and our own inadequacies onto a victim for what they are: a moral failing, projected violently upon someone else. Christ is the scapegoat who reveals our imperfections, and forces us to look at our own flaws rather than blame our society’s chosen victims.”

We are none of us masters of our fate. How could we be, on this view, given that our desires are fundamentally derivative and mimetic? But the answer, it turns out, is not to pin the blame for the problems of our community on structural or social forces. Spiritual, not social, reform seems to be the solution on offer. Vance sees in Christ’s status as voluntary victim a more appealing path. Vance’s Girard thus offers an account of the pathological tendency to blame others for our own problems, but the precise ways that this insight overcame the contradiction between social determination and moral responsibility are vaguely developed. Just as Vance arrives at this moment in his account of his intellectual formation, the narrative breaks off. Vance changes the subject again.

Is it much of a stretch to imagine that Thiel sees in Christ a portrait of himself as a (job) creator?

One wonders how Vance reconciles such claims, which purport to be grounded in compassionate self-criticism, with his recent blatant scapegoating of Haitian immigrants and refugees in Springfield, Ohio. Whatever the answer, there can be no doubt that Vance has engaged at some length with a philosophical literature that expounds on the way that scapegoating is used as a myth to maintain social order and redirect the passions of the unenlightened populace. When Vance invents stories and spreads racist memes about the effects of offering refuge to Haitians living in Springfield, Vance seems to be hoping to revive such inflammatory myths.

One might argue that the alliance between Thiel’s odd brand of techno-libertarianism and Vance’s pro-natalist Catholicism is hardly new in the history of conservative thought. After all, this alliance has an antecedent in the fusionism that William F. Buckley Jr. and Frank Meyer forged at National Review in the 1950s. Fusionism brought together social conservatives, free marketeers, and anticommunist hawks, reaching its apogee with the election of Ronald Reagan. And as Melinda Cooper argues in her 2019 work Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism, free-market thought leaders like Milton Friedman and Gary Becker had remarkably conservative social visions, which put the patriarchal nuclear family at the center of their worldview, as a replacement for the liberal welfare state.

The old fusionism is sometimes criticized by the post-liberal right for focusing too much on individual autonomy. “[The libertarian] focus on economic expediency treats the average person as a cog in the economic machine,” writes Joey Barretta. “Likewise, the culture of license that libertarians promote in their base view of liberty is antithetical to the morals of the average person.” A collectively authored essay in First Things declared that there was no going back to a pre-Trumpian conservatism and that “conservatism too often tracked the same lodestar liberalism did—namely, individual autonomy. The fetishizing of autonomy paradoxically yielded the very tyranny that consensus conservatives claim most to detest.” But Cooper’s book shows that this criticism is at best exaggerated. Neoliberal anthropology is not liberal anthropology; the free individual is replaced, under neoliberalism, by a vision of the human as a highly malleable bundle of human capital, and children are in this view nothing if not part of a family’s portfolio of human capital.

The political alliance of Thiel’s libertarianism and Vance’s pro-natalism appears to follow the same playbook. Indeed, a more properly materialist analysis of what Thiel and Vance share might note that they are both products of what Robert Brenner called the Long Downturn, the era of falling profitability, deindustrialization, and waning union power that started in the early 1970s. Thiel is nostalgic for an era of wild economic growth that characterized the postwar American boom economy; but he would rather blame spiritual problems for the lack of sustained growth than blame macroeconomic forces or neoliberal policies that emphasized increasing returns to capital rather than labor. Likewise, Vance’s pro-natalism and paeans to the white working class similarly valorize a lost moment of (highly unionized) strength but redirect the conversation again to frankly silly—though no less frighting—neo-fascist attacks on “the Cathedral,” the Deep State, or whatever absurd neo-Tolkienesque meme the online right will whip up next.

We are none of us masters of our fate. How could we be, given that our desires are often derivative and mimetic? But the answer, it turns out, is not to pin the blame for the problems of our community on structural or social forces. Spiritual, not social, reform seems to be the only solution on offer.

But Thiel’s and Vance’s relationship to Girard complicates this claim. After all, what united the original fusionists was an arch anticommunism. To be sure, they had domestic rivals and opponents, but the binarial distinction between friend and enemy imagined the United States as standing in opposition to an outside force that had to be defeated for the good of the whole world. Vance and Thiel, by contrast, carve the world up in different ways, seeking not so much to reform the world as to exit it and await the Second Coming. If Girard is right that there is no avoiding generalized mimetic violence in a postmodern world, perhaps the best one can do is build an ark—an authoritarian seastead community, or techno-feudal charter city, inspired by the Foundation of Asimov’s famous science fictional series—and wait for the coming deluge. But one must first defeat the federal bureaucrats who would stop the building of such a refuge.

Thiel has articulated a vision of sea-steading, spacefaring, cyber-libertarian utopias that seems impatient with the very form of the sovereign nation-state. His rhetoric has become more nationalistic in recent years, but his authentic vision for a better future more resembles calls for charter cities—what Balaji S. Srinivasan has called the “Network State,” or what Yarvin calls “the Patchwork,” all of which purport to bypass traditional politics by exiting the nation and allowing a thousand neo-fascist or techno-libertarian flowers to bloom, free of the meddlesome constraints of bureaucrats and technocratic liberals.

Before he became Trump’s vice-presidential pick, Vance said in a podcast interview that he thought Trump should prioritize dismantling the institutions that make up the federal bureaucracy. Trump should “seize the institutions of the left,” fire “every single midlevel bureaucrat,” and ignore the Supreme Court if it tried to stop him, following essentially the playbook laid out both by Curtis Yarvin and, more recently, the authors of Project 2025. “I saw and realized something about the American elite, and about my role in the American elite, that took me just a while to figure out. I was redpilled,” Vance explained in another interview. “We are in a late republican period…. If we’re going to push back against it, we’re going to have to get pretty wild, and pretty far out there, and go in directions that a lot of conservatives right now are uncomfortable with.” Far out, man.

The real enemy that unites Thiel and Vance can therefore be found within the nation and among nations that seek to exercise democratic sovereignty.

Thiel is nostalgic for an era of wild economic growth that characterized the postwar American boom economy; but he would rather blame spiritual problems for the lack of sustained growth than blame macroeconomic forces or neoliberal policies that emphasized increasing returns to capital rather than labor.

There are endless complications kicked up by this effort to resist and exit the profane world of secular mimesis gone wild.

One might note, for instance, that a firm like Thiel’s Palantir Technologies is straightforwardly complicit in the national security apparatus that Thiel might, if he were an actual opponent of state power, condemn. Among its other contracts, Palantir provided software that helped U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement build profiles of potential targets of deportation. As Brian Doherty has noted in Reason magazine, Thiel can often seem less like a libertarian these days and more like an outright nationalist.

And Vance is, of course, running to become vice president of the Deep State he otherwise rails against. If Vance were to become president, one could be sure that he would enthusiastically use the full force of the Deep State to achieve many of his aims. And of course for all Trump’s alleged populism, one might argue that he governed more like any run-of-the-mill Republican, slashing tax rates for billionaires, radically mismanaging the federal bureaucracy, and polarizing our politics even further.

Our challenge then, when assessing the significance of Vance and Thiel’s shared commitments, is not exactly to take their ideas seriously—for their ideas are often profoundly silly, even when dressed up with the philosophical jargon of mimetic desire—but rather to consider the possibility that we should take them very literally. When Thiel tells us that he “no longer believe[s] that freedom and democracy are compatible,” we need to understand that he might well mean exactly what he says and that, through the election of J. D. Vance, he might soon get exactly what he desires.