For seventy years, it has been the law of the land: pastors may not tell their flocks what name to check at the ballot box. To officially endorse any candidate—even one who attends the same church—is to risk the punishment of the Internal Revenue Service, which can revoke a church’s tax-exempt status as punishment for political activity.

And while the law is still on the books, in early July, the IRS agreed, in response to a lawsuit brought by a group of Texas-based religious broadcasters and churches, to a carve-out some conservative religious leaders have dreamed of for years: the freedom to campaign for a politician from the pulpit.

In a filing settling the lawsuit, both sides likened a pastor’s politicking to “a family discussion concerning candidates.” Then they spelled out what has been an unspoken practice since the last century: “Communications from a house of worship to its congregation in connection with religious services through its usual channels of communication on matters of faith do not run afoul” of the law.

After seven decades of looking the other way, why officially carve out an exemption for churches now? What effect, if any, will this clarification of the law have on American religious freedom and political campaigns?

“The worst case scenario is that church and state get too close, and when that happens, churches lose,” said Lloyd Hitoshi Mayer, a professor of law at Notre Dame. “They become arms of political parties and feel pressure to take sides they otherwise would not take.”

The relevant law, known as the Johnson Amendment, is seen by some as a sturdy divider between church and state, by others as an unconstitutional ban on free speech. It was added to a larger bill before Congress in 1954, by Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson, when Americans’ fear of Communism was at a boil. Johnson, a Democrat, was facing a tough election at home and wanted to ensure his opponent did not get the backing of Texas non-profits, whose leaders considered Johnson “soft” on Communism.

The amendment was aimed at all non-profits, not just houses of worship. It forbids them to “participate in, or intervene in … any political campaign on behalf of … any candidate for public office.” To do so was to risk the tax-exempt status houses of worship enjoy. The bill containing the amendment passed easily, and Johnson won his election.

After seven decades of looking the other way, why officially carve out an exemption for churches now? What effect, if any, will this clarification of the law have on American religious freedom and political campaigns?

But the Johnson Amendment has only rarely been enforced. This despite “Pulpit Freedom Sunday,” an annual event, begun in 2008, in which pastors—mostly evangelicals—openly promoted one candidate in their sermons, which they then sent copies of to the IRS. The IRS has penalized only one church, a Binghamton, N.Y., congregation that in 1992 took out full-page ads in a local newspaper, urging people not to vote for Bill Clinton.

Part of the answer to “why now?” is surely political payback. President Trump has said he sought the endorsement of religious groups when he ran for president in 2015, but the law blocked him. A repeal of the Johnson Amendment was on the wish list of his evangelical backers. In his first term, Trump weakened the Johnson Amendment through an executive order. Only an act of Congress can repeal it.

But Congress has shown no will to overturn the Johnson Amendment. Attempts in 2017 and earlier this year failed. So while this recent action does not overturn the law, it does the next best thing, from the Trump Administration’s point of view—putting in writing, for the first time, the IRS’s unspoken policy of ignoring pulpit politics.

Still, the action has some legal scholars scratching their heads. The carve-out is very narrow and seems to apply only to the two churches and religious broadcasters who filed suit against the IRS. Mayer, the Notre Dame law professor, thinks it is a signal from the Trump Administration of its hands-off attitude toward political speech from the pulpit.

“But the law is still on the books, so a new administration could reverse that,” Mayer said. “So it’s an incentive for churches to say, ‘Oh, we better make sure you stay in power.’ It could be used as a ploy to scare churches into endorsements.”

Other non-profits must reveal their major donors to the IRS, but churches, by law, are exempt from this rule. That privacy, combined with this carve-out, means “churches could become dark money on steroids,” said Phil Hackney, a professor of law at the University of Pittsburgh. “It creates a big incentive for wealthy donors to make large contributions with political strings attached to churches. It’s an end-run around our system, and I don’t think that’s good for democracy or good for our churches.”

Brad Jacob, a professor of law at Regent University, a Christian school founded by the late televangelist Pat Roberston, agrees. Jacob lauds the action for upholding pastors’ free speech and free exercise of religion. But “that doesn’t mean I am in favor of pastors endorsing political candidates,” he said.

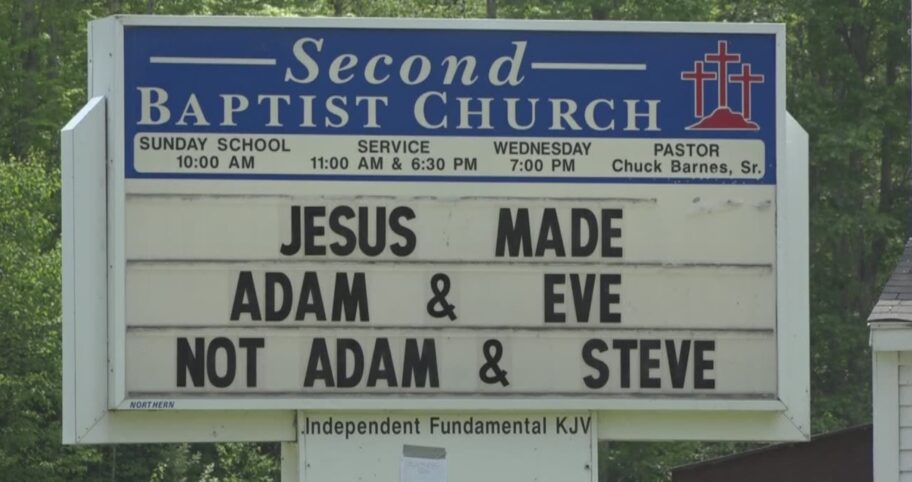

“A church that starts to endorse candidates is dangerously close to saying, ‘This political candidate stands for everything we believe in, and if you are a good Christian or Jew, you think so too,’” Jacob said. “I just think it is a far wiser position for a faith community to say, ‘We want to give our own people room to use their own conscience and discernment.’”

Most Americans seem to agree—77 percent say they do not think pastors should endorse political candidates, according to the Pew Center. Reaction from religious organizations has been mixed. Some evangelical leaders, especially those with ties to Trump, have heralded the change.

“This would have never happened without the strong leadership of our great President Donald Trump!” Robert Jeffress, a Dallas pastor who sat on Trump’s Evangelical Executive Advisory Board, wrote in an X post. “Government has NO BUSINESS regulating what is said in pulpits!”

Other leaders have expressed caution. The Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism issued a statement calling the decision “deeply misguided” in a time of hyper-partisan politics and expressing worries that it would threaten “the congregation’s status as a place where all feel welcome.”

But the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops had a more ho-hum attitude. “[I]t doesn’t change how the Catholic Church engages in public debate,” spokesman Chieko Noguchi said in an official statement. He said that the “Catholic Church maintains its stance of not endorsing or opposing political candidates.”

Mayer is hopeful the change will be negligible. “The IRS was always reluctant to audit a church in the first place, and when it did, it was reluctant to impose a significant penalty,” he said. “The landscape has not really changed.”