Here’s a picture familiar to most Jews: it’s Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year. A Torah reader clad in white ascends to the front of the sanctuary to chant the story of the scapegoat, the biblical tale in which a goat bearing the sins of the Jewish people is sent into the wilderness to its death. On the somber Day of Atonement, Jews listen to this story of sacrifice and sin, read in Hebrew from the Book of Leviticus, as they consider the ways they have done wrong in the prior year.

What is never part of that picture, unequivocally, is an actual goat. The destruction of the Temple two thousand years ago marked the end of ritual sacrifice for the Jewish people. Instead, the ancient practices of the Hebrew priests are described in the Bible and recited weekly. Jews are the people of the book, not the people of the reenactment.

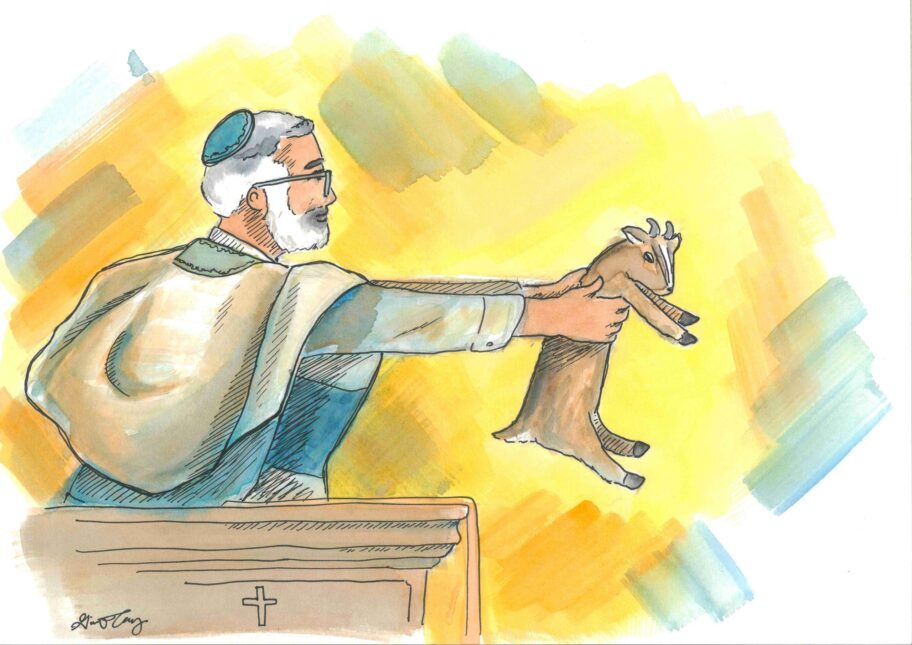

None of that mattered to Rabbi Peter Oliveira on the morning this past winter that he held a baby goat and climbed the steps to a makeshift platform behind the pulpit of his Connecticut congregation. Barefoot, wearing a yarmulke on his head and a Jewish prayer shawl around his shoulders, he dangled the goat over the platform at least twenty feet above the ground. Parishioners gasped.

But Rabbi Peter was not merely a renegade rabbi pulling a stunt to explain a biblical tale. As he tenderly held the goat, Rabbi Peter spoke to the members of the First Congregational Church of Litchfield not as a rabbi but as a pastor—or, rather, a pastor who is also a rabbi, and a Christian who is also a Messianic Jew. He carried the goat to that precarious spot to make a point not about Judaism but to preach about the most famous Jew of all: Jesus. In Rabbi Peter’s version of this story from the Hebrew Bible, the scapegoat was Jesus—Yeshua, as he called him, in Hebrew.

“Yeshua would be the one that would have all the sins of the world put on him, as he was killed for the salvation of the people of Israel,” Rabbi Peter said to a hushed crowd. Some people stood, palms up in reverence. “Hallelujah,” someone chanted. “Glory.” The room filled with applause and whoops.

To the current members of First Congregational, up in this rural, leafy northwest corner of Connecticut, Rabbi Peter is something of a savior himself. In 2020, he took over the leadership of this historic three-hundred-year-old church at a moment when its membership was at an all-time low and rebuilt it into a vibrant, dynamic community—the kind of place where people know each other, and where nearly one hundred congregants fill in the pews even on a cold, gray Sunday in January. That he stepped into the role of pastor just weeks before the Covid-19 pandemic and managed not just to keep the church’s doors open but also to dramatically grow the size of its regular worship service during that fraught period contributes to the air of chosenness that surrounds Rabbi Peter.

“In the times that we’re living in, when there’s so much insecurity and so much hatred, so much hopelessness, to be able to have a community of faith where people feel supported, uplifted and spiritually fed in their souls—I think that is transformational,” said Catherine Vlasto, a social worker who has been going to First Congregational for more than two decades.

The ladies volunteering at the used bookstore in the church’s basement will tell you directly: “Our pastor is a rabbi.”

There is nothing inherently interesting about the fact that a small church in a small town, located in the part of Connecticut that New Yorkers flock to in the summer but forget about the rest of the year, chose a new pastor. But listen to the way the members of First Congregational talk about him, and you’ll hear an unusual reverence in their voices as they describe their atypical choice of spiritual leader. The ladies volunteering at the used bookstore in the church’s basement will tell you directly: “Our pastor is a rabbi.”

It’s a point of pride for church members, something they think distinguishes their community from the dozens of other Congregational churches scattered across town greens in New England. Many of First Congregational’s members see a so-called rabbi leading a Christian congregation and think it’s not far off from how Jesus himself lived.

“I appreciate that about Rabbi Peter being different in that way,” Vlasto explained. “Jesus was an outsider. He was a Jewish guy who was seen by his community as a blasphemer, someone who was making these incredulous claims, and he was crucified because of that.”

In the United States today, Rabbi Peter is not just an outsider but a contradiction in terms. A rabbi as a pastor? A Jew leading a church? How can it be?

First Congregational Church of Litchfield was founded in 1721. It was a recruitment center for George Washington’s army during the Revolution. Less than a century later, its most famous pastor, Lyman Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s father, advocated from its pulpit for the abolition of slavery. This was a storied place, but lifers feared its story might soon end. By 2019, the church was in the midst of a steep decline. Worshippers were not coming; coffers were not being filled.

That’s when the leadership asked Rabbi Peter if he’d consider becoming the pastor. He was already leading a Saturday Shabbat service inside the church as part of his messianic congregation, called Mishkahn Nachamu.

“I said, ‘I’m not a pastor,’” Rabbi Peter recounted over lunch, after the Sunday service in January ended, and the baby goat was safely returned to its owner. He washed down his steak frites with an old fashioned. “They just kept asking.” Eventually, he said yes.

Rabbi Peter was not at all sure that, as a funky, spiritual guy with a goofy smile and a love of singing and props and Hebrew words, he would feel comfortable taking on the leadership of a stuffy old mainline Protestant church months away from bankruptcy. His question was whether he would be a good fit for the congregants’ worship style. But that wasn’t the question that brought me—a boring, old-school non-messianic Jew (or, as I would call myself, a Jew)—to cold New England in January.

As I walked into the nearly hundred-year-old chapel—the original meetinghouse had long since been replaced and reconstructed several times over—my question was more direct and, in a not very Jesus-like way, more judgmental: what was this guy doing telling churchgoers that a rabbi can be a pastor, as if there’s no difference between Judaism and Christianity?

Because a rabbi, of course, cannot be a pastor—not if you respect the fact that Judaism and Christianity are different religions with their own distinct faith traditions. Rabbis are Jewish spiritual leaders, and Jews do not believe that Jesus was the messiah. As Mark Oppenheimer wrote in this magazine last year, discussing David Brooks’s attempts to identify with both Judaism and Christianity: “There is a name for people who believe in the ‘whole shebang’ of Judaism and Christianity: they are called ‘Christians.’”

“I said, ‘I’m not a pastor,’” Rabbi Peter recounted over lunch, after the Sunday service in January ended, and the baby goat was safely returned to its owner.

The Messianic Jewish movement is relatively new, at least in the sweep of Jewish history, dating back just decades to the 1970s and the counterculture era.

“To both Jews and Christians, Jews were Jews, and Christians were Christians. But the generation that came of age in the 1960s and 1970s thought differently about these matters,” writes Yaakov Ariel, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an expert on Messianic Jewish practices. “They wanted to make their own choices and did not feel constrained by old boundaries and taboos. Judaism and Christianity could go hand in hand.”

But almost immediately, Jewish religious leaders were skeptical. One particular sect of Messianic Judaism, Jews for Jesus, vigorously proselytized Jews. Rabbis developed educational materials to help young Jews avoid the sway of Jews for Jesus evangelists.

Today, there are hundreds of Messianic Jewish congregations in the U.S., each with its own unique traditions and observances. “None, however, have made the claim that there is a requirement to observe Jewish rites in order to be justified in the eyes of God,” writes Ariel.

In Rabbi Peter’s world, gone were the ritual commandments of Judaism. In their place were Jewish symbols as if dropped from the sky—a Torah and a kiddush cup on the stage, more for aesthetic than utilitarian purposes; a Star of David necklace around the neck of a Christian woman in the pews. Christians do not follow the 613 commandments, or mitzvot, that guide Jewish law; they believe that Jesus released them from specific commandments. So to pretend to obey them can seem, to those who do follow Jewish law, like a form of play-acting.

Rabbi Peter’s Judaism had all the fun parts of being Jewish but none of the obligation to God or to one’s fellow Jewish community. Who wouldn’t want to enjoy some challah while skipping the other laws of the Sabbath?

I watched as Rabbi Peter performed the priestly blessing in Hebrew over the members of his church congregation. He called God “Adonai,” the Hebrew word used in Jewish prayers. He invited the children up to sit under a “chuppah,” the Hebrew word for a Jewish wedding canopy, where he blessed them.

Theirs is a world in which definitions don’t matter, so long as you believe in Jesus. To Rabbi Peter, that’s a pretty good way to live. But is he a Jew or a Christian? He didn’t want to choose.

“I kind of see myself as a bridge, making a connection,” he said. His goal, he said, is not to make the members of the church identify as Messianic Jews; he instead wants them to understand Judaism, so they can better understand Jesus and the way he lived.

“In the Christian mindset, people tend to have more of a thing of, ‘If you’re Christian, then you can’t hold on to any of that Torah stuff,’” he said. “I feel like Adonai wants to break down that barrier and find almost, like, a bridge. The purpose of a bridge is just to connect two things, so people can go back and forth. They can still go to either side.”

I wondered what this group of Christians from rural Connecticut thought of all of it.

“Having him wear that little cap on his head or not, he’s just so cool,” said Donna Molon, who’s been a member of First Congregational for a decade. “He really is. It doesn’t bother me one bit that he’s Jewish.”

Catherine Vlasto, the longtime church member who compared Rabbi Peter to Jesus, was more clear-eyed on the question of identity. “Do I see Rabbi Peter as a Christian? Yeah, the definition of a Christian is someone who believes in Jesus Christ,” she said. “He is. I also see him from a Jewish perspective, because he has embraced that.”

“Having him wear that little cap on his head or not, he’s just so cool.”

No one could quite explain it—how it works, who Rabbi Peter is, why he’s so beloved.

Peter Spungin goes to the weekly Sunday services at First Congregational as well as the Saturday Shabbat service. Spungin grew up in a traditional Jewish community but found his way to messianic communities later in life, when he started believing in Jesus.

“I’ve never experienced anything like Rabbi [Peter],” Spungin said. “Rabbi, he’s a rule breaker. And of course, Yeshua”—Jesus—“was the biggest rule breaker of them all.”

Rabbi Peter’s journey to Litchfield beggars belief. It is a tale of family and faith, religious reckonings and crises of faith, a sailboat in the Atlantic and the warmth of strangers. Buying into his story wholesale is like believing in the Bible: confusing, contradictory, and full of inexplicable miracles.

Peter Oliveira grew up in Angola, an African nation once colonized by Portugal, the land to which he now traces his roots. His parents were Seventh-Day Adventist missionaries. (Seventh-Day Adventists are end-time Christians who, like Jews, observe the Sabbath on Saturday.) Rabbi Peter described it as a “cultish” upbringing, in which he was forced to memorize the Old Testament, an unusual skill that later set him on the path toward Messianic Judaism. But when he first left home, he spurned religion.

“When we were dating, I said to him, ‘Don’t think about becoming a pastor, because I do not want to have a pastor husband. That is not my plan for my life,’” his wife, Lisa, said at our lunch. She, too, had grown up a Seventh-Day Adventist and left it behind. They settled in Rhode Island, and Rabbi Peter worked at a biotech company near Boston.

The story of what happened next is a bit fuzzy at the edges. Which is part of the point.

“At the age of thirty, I had this huge, shaking enlightenment where I just started gravitating to all these Hebraic things that made no sense to me,” Rabbi Peter said. He found himself drawn toward Jewish objects like prayer shawls and shofars. He took his three sons to see The Prince of Egypt, the 1998 animated movie that tells the Passover story of the Jews leaving Egypt. When one of the characters began singing in Hebrew, he cried.

Rabbi Peter soon asked an aunt if it was possible their family had Jewish ancestors.

“She looked at me, she’s like, ‘What kind of stupid question is that? Your dad never told you?’” he recalled. “’Because we’re descendants of Aaron.’” Apparently, his father’s family was descended from the ancient Kohanim, the Jewish priests. In many Jewish families, the priestly lineage is known, knowledge of it handed down—and no one had ever told Rabbi Peter. His father had tried to hide the fact that, hundreds of years ago, their Jewish relatives had escaped to Angola during the Portuguese Inquisition.

This revelation upended Rabbi Peter’s life. “I felt a disconnect, because now I felt like, where do I belong? Who am I? I was really struggling with that.” He began learning about Judaism and, not wanting to disavow the faith in Jesus that he maintained even after leaving the Seventh-Day Adventist community, quickly gravitated toward Messianic Judaism.

He found a messianic congregation in Foxboro, Mass., and became a regular there on Saturdays. (Many Messianic Jewish congregations, in deference to Judaism, hold services on Saturday.) He took what he called a Nazarite vow—a concept based on the book of Numbers—and did not drink wine or cut his hair for three years. “I looked very Orthodox,” he joked.

All kinds of other mystifying things happened during this time, he said. The night before the 9/11 attacks, Rabbi Peter was talking with some colleagues about his newfound faith and shared a “prophecy” with them that, he claimed, got him put on the FBI’s terror watch list and almost sent to the prison at Guantanamo Bay.

“I said, you know, when a nation turns away from Adonai … anyone could come into this nation,” he recalled. “They could use little box cutters and take over an airplane and smash it into buildings and turn this whole nation into chaos. I said that. I had no idea why I said that. Everybody thought I was crazy. And then the next morning, like, it happened.”

Rabbi Peter did not go to Guantanamo, and eventually he shaved his beard, and he continued on his journey. At this point he was just Peter, not yet a rabbi, and he had no intention of becoming one, until the rabbi at his Foxboro congregation announced one day that Peter, too, would be a rabbi.

“I served a rabbi for seven years,” he said, although his description of what it meant to be a “rabbi” does not accord with traditional Judaism, or any other religion. He was a jack-of-all-trades for the congregation. “Basically, ‘I need this window replaced.’ ‘I need this toilet fixed.’ ‘I need you to pray over this person.’ ‘I need you to read this in the Torah.’ I was just serving with no intention of, like, going to school.”

Rabbi Tobi Hawksley, Rabbi Peter’s old rabbinic mentor, is now retired in small-town Maine, her congregation in Foxboro long shuttered. “When you’ve worked as a clergy for a certain amount of time, you get a sense of who’s very serious about what they’re doing, who has an intense sense of spiritual things,” she told me. “I did feel that Peter was called to the ministry.”

By his own admission, Rabbi Peter never received any kind of training—just a kick in the behind from his mentor, Rabbi Tobi.

“One day, my rabbi called me up and said, ‘Adonai is sending you out to be a rabbi. It’s time,’” he recalled. “I said, ‘No, not me. I’m the wrong person for that job.’”

But miracles and wonders kept befalling Rabbi Peter. “One day, a man called me up and said, ‘I need to meet with you, and I have a key to give you.’ It was a key to a little old 1800s schoolhouse,’” recalled Rabbi Peter. “He said, ‘There’s no cost. You just use this building, and I’ll come back in nine months to see what happened.’”

He started a messianic congregation in that schoolhouse, in a suburb of Providence, R.I., and worked there from 2005 to 2013, until he and his family moved to Haiti to run an orphanage. They stayed in Haiti for five years, living in a sailboat docked just offshore, supported by funds raised from generous believers.

“I’ve been told I’m one of the wealthiest people without any money,” Rabbi Peter said. “I don’t know what that means. I just have favor. I don’t know what to say. I don’t ask people for anything. And sometimes people come up and bless us.” He was renting the land where the orphanage was located, until the owners told him they were going to sell it unless he could buy the property.

“I just started praying about it. I needed $30,000 to buy the property,” he said. “I never asked anyone. I just prayed and prayed and prayed and then one day, this man called and said he wanted to meet with me.” The man told Rabbi Peter that God had told him to write a check for $30,000 to save the orphanage. “I don’t know,” Rabbi Peter added. “I just have favor.”

Rabbi Peter later got a sign that his family’s time in Haiti was up. (It didn’t help that the money dried up.)

“I just heard a loud thought in my mind say, ‘Your mission here is complete. Return to the U.S.,’” he recounted. “Then, as if the giver of that thought could hear the bewilderment in my mind, I heard another thought. ‘Go to the region of Washington, Connecticut, and start a new congregation. Name it Mishkahn Nachamu, comfort my people.’”

The region was not totally random; he and Lisa had some friends in northwest Connecticut, who connected them to other faith-inclined locals. “When we came [back] from Haiti, there was a family who welcomed us to stay at their home, so we didn’t have any bills when we came here. That was an amazing blessing.”

He knocked on the door of nearby churches, asking if he could set up a Saturday prayer service for Messianic Jews. Only First Congregational of Litchfield said yes. He began holding services—on Saturdays; the Congregationalists met on Sundays—and over the course of a year, he quietly spread the word around the region, bringing together an eclectic group, united less by any particular religious belief than by a shared sense of seeking. He called the new congregation Mishkahn Nachamu—“Tabernacle of Comfort” in Hebrew. His congregation overlapped with, but was not the same as, the Christian congregation that met on Sundays. Rabbi Peter’s was a ragtag bunch of people to whom life had not always been kind, and the rabbi’s peculiar, judgment-free zone became a sanctuary to them.

“I had a broken life,” said Peter Spungin. “My wife had some things broken in her life. I found Yeshua in that brokenness, and I would never trade my life for anybody else’s life.” He and his wife love that Rabbi Peter has a service on Rosh Hashanah, which they celebrated in their youth at traditional synagogues, and that he performs a Passover seder, or something like it. They usher in autumn at Mishkahn Nachamu’s Sukkot celebration, which Rabbi Peter called “a Jewish Woodstock without the drugs,” where more than two hundred people sleep in tents and camper vans on a field to mark the Jewish fall harvest festival.

I, too, celebrate Sukkot, but in the less groovy way that is outlined in the Torah: with a small, temporary hut built in the backyard, where my family eats meals and hosts guests. In a recent conversation, the writer Dara Horn described the essence of Judaism to me as a two-letter word in Hebrew: Am. People. Being Jewish means being a member of Am Yisrael, the Jewish people. Jesus may have once been part of Am Yisrael, but he strayed from it. Two thousand years of Jewish exile and awaiting the Messiah, who we Jews believe has not yet arrived, have cemented that divide.

“All Jews, in essence, are messianic,” Rabbi Peter said cheekily. “We may not all agree on who the messiah is.” He is well aware of the negative connotations of Jews for Jesus, the branch of Messianic Judaism popular in the 1970s and 1980s that was generally considered to be Christian proselytizing in disguise. He insists that his form of Messianic Judaism, which is not connected to any larger organization or movement, is not that. There’s no hidden agenda, he promises. “I do not support in any way people trying to proselytize and convert people. I feel that our call is to awaken, not convert.”

That works “both ways.” In church on Sundays, “I’m not trying to make a Christian person Jewish,” he said. “I want whatever I share to awaken them to become a better Christian.”

Likewise, he added, “with a Jewish person, I don’t want them to be converted into anything. I just want them to realize, ‘Oh my gosh, this is my scripture, this is my Moshiach.’”

I asked Rabbi Peter if he saw value in the fact that some people—many people—do see a difference between Judaism and Christianity, that they see value in those dividing lines between the two faiths.

“Be true to what you know in your heart you were supposed to do,” Rabbi Peter said. “I think they better do what Hashem”—God—“puts in their heart to do. If Adonai tells them, ‘You have to hold on strictly to this Hebraic thing,’ you better do it, because at the end, you have to stand before Him.”

In my head, I prepared a list of rebuttals, trying to reason my way out of this conversation and figure out just what he meant. But you can’t get to the bottom of a dispute about faith.

“It’s not a logical thing to answer,” Rabbi Peter said. “We’re all seeking.”

“I felt a disconnect, because now I felt like, where do I belong? Who am I?”

At the First Congregational Church on Litchfield, no one is thinking about the correct word to describe Rabbi Peter’s faith. All they see is a man who has transformed a failing New England church into a congregation that is warm, upbeat, meaningful.

With First Congregational’s old pastor, “we would all sit there like little church mice. ‘Okay, you’re in church, now you fold your hands, you sit there, you behave,’” said Donna Molon, the First Congregational regular. “But now with the Sundays, we’ve got more people coming from the Saturday services, and everybody likes to stand up and hoot and holler.”

It’s not because the room has turned into a devout group of Messianic Jewish true believers. They are true believers in Peter Oliveira, a pastor who is a rabbi, a Christian who believes he is a Jew. “He never can leave that church,” said Molon. “He’s gonna be there forever.”