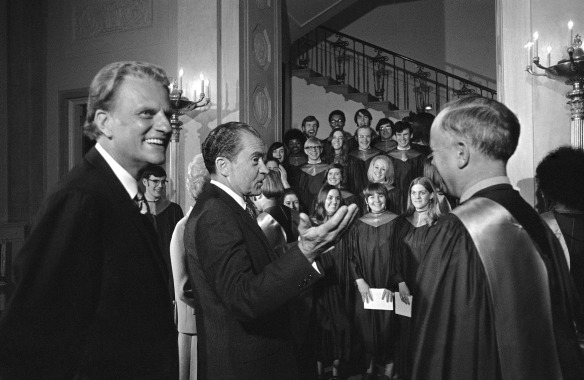

When Richard Nixon entered the White House, he brought his good friend Billy Graham with him. A constant presence and trusted adviser, the minister became, in the words of biographer Marshall Frady, “something like an extra officer of Nixon’s Cabinet, the administration’s own Pastor-without-Portfolio.” Others were more critical. Will Campbell, a liberal southern preacher, denounced Graham as “a false court prophet who tells Nixon and the Pentagon what they want to hear” while journalist I.F. Stone dismissed him as a “smoother Rasputin.” Whatever the critics said, Graham’s influence in the Nixon White House was profound. With his blessing, the Nixon White House gave new life to old public rituals and, more importantly, created religious ceremonies of its own.

Of all the religious rites and rituals launched in the Nixon administration, the most remarkable was the new practice of church services held inside the White House. “I’ve never heard of anything like it happening here before,” White House curator James Ketcham told Time. The semi-regular services took place in the East Room, a showcase space noted for its sparkling chandeliers and gold silk tapestries. Instead of pews, oak dining room chairs with seats of yellow brocade were arranged in rows of twenty. A piano and an electric organ, donated to the White House by a friendly merchant, were positioned at the north end of the room, with space to the side for a rotating cast of choirs to perform. Between them stood a mahogany podium where the president and the “pastor-of-the-day” would make remarks.

Naturally, Billy Graham presided over the initial White House church service, held the first Sunday after the inauguration. As worshippers entered the East Room, they picked up liturgical programs, adorned with the official presidential seal, and found their way inside, while a Marine master sergeant played soothing hymns on the organ. Soon, every one of the 224 seats in the room was taken, with two thirds of the Cabinet and several senior staffers on hand; still more stood at the rear. As large portraits of George and Martha Washington looked on, Nixon strode to the podium, welcomed the assembled to “this first worship at the White House” and invited up his “long-time personal friend.” Graham graciously returned the compliment, using the president’s inaugural address as the basis for his remarks. He urged the country to heed Nixon’s warnings about the “crisis of the spirit” that was sweeping across college campuses and asked God to guide the administration as it dealt with that problem and others. When the service concluded, White House waiters ushered guests into the State Dining Room for coffee, juice and sweet rolls. As they went, they passed through a receiving line made up of Nixon, Agnew, Graham and their wives. Shortly after, Graham and the Nixons posed for photographers on the north portico. A delighted Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman raved about the day in his diary: “Very, very impressive.”

Some outside the White House were less impressed, denouncing the services as crassly political. One minister, for instance, complained to the New York Times that “the president is trying to have God on his own terms.” The administration and its allies replied indignantly to allegations that Nixon was politicizing religion. “The President would be appalled at the thought,” insisted Norman Vincent Peale. “The White House, after all, is Mr. Nixon’s residence. And if there’s anything improper about a man worshiping God in his own way in his own home, I’m at a loss to know what it is.” Graham agreed that the White House services were simply a private means of sincere worship. “I know the President well enough,” he protested, “to be entirely sure that the idea of having God on his own terms would never have occurred to him.”

Behind the scenes, however, ulterior motives were clear. “Sure, we used the prayer breakfasts and church services and all that for political ends,” Nixon aide Charles Colson later admitted. “One of my jobs in the White House was to romance religious leaders. We would bring them into the White House and they would be dazzled by the aura of the Oval Office, and I found them to be about the most pliable of any of the special interest groups that we worked with.” The East Room church services were crucial to his work. “We turned those events into wonderful quasi-social, quasi-spiritual, quasi-political events, and brought in a whole host of religious leaders to [hold] worship services for the president and his family – and three hundred guests carefully selected by me for political purposes.” Notably, Haldeman was deeply involved in the planning. Before joining the administration, he had been an advertising executive at the J. Walter Thompson Company, back when it handled promotions for events such as Spiritual Mobilization’s “Freedom Under God” ceremonies and the Ad Council’s “Religion in American Life” campaign. Well versed in the public relations value of public piety, Haldeman exploited the services to their full potential. At his suggestion, for instance, the supposedly private programs were broadcast over the radio, with print reporters, photographers and TV cameramen on hand to record the spectacle for wider distribution.

In keeping with this political stagecraft, the White House staff went to great lengths to guarantee that clergymen invited to preach were conservatives connected to a major political constituency. In recommending Archbishop Joseph Bernardin of Cincinnati for a service before St. Patrick’s Day, a cover memo noted bluntly that “Bernardin was selected because he is the most prominent Catholic of Irish extraction and a strong supporter of the President. We have verified this.” Harry Dent, a former aide to Strom Thurmond who directed the administration’s “southern strategy,” likewise forwarded a list of “some good conservative Protestant Southern Baptists” who could be trusted to preach a message that pleased the president. Graham helped as well. When Nixon sent an emissary to the Vatican and unwittingly upset Baptists, Graham suggested inviting Carl Bates, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, to preach in the East Room “might negate some of the criticism.” Likewise, in 1971, Graham encouraged the White House to invite Fred Rhodes, a lay preacher who seemed sure to run for the SBC presidency that year. An internal memo enthusiastically noted that Rhodes was a “staunch Nixon loyalist.” “A White House invitation to speak would aid greatly in his campaign for this office,” the memo continued, “and if elected, Colson feels that Rhodes would be quite helpful to the President in 1972.”

Political considerations dictated the selection of speakers in more obvious ways. In September 1969, for instance, Reverend Allan Watson of Calvary Baptist Church in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, served as the East Room officiant. After the services, Watson posed with the president for the now-customary photograph on the north portico. They were joined by his twin brother, Albert Watson. A congressman who had abandoned the Democratic Party over its support of civil rights, he was at the time running for governor of South Carolina as a Republican. To the delight of Harry Dent, who had made arrangements for the visit, the photograph circulated widely in the campaign. Likewise, in February 1970, Reverend Henry Edward Russell of the Second Presbyterian Church of Memphis was given the honor of leading the East Room services. Many of his family members attended, but reporters paid particular attention to his brother, Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, who happened to chair the committee that would soon pass judgment on Nixon’s prized plan for an antiballistic missile treaty.

Political concerns also dictated who attended each service. The congregation was typically composed of prominent members of the Nixon White House and its supporters, so much so that the New York Times joked: “The administration that prays together, stays together.” Invitations usually went to allies in Congress, but occasionally they were used to lobby more independent members about particular bills. In July 1969, as the Senate deliberated the antiballistic missile treaty and the House considered an anti-inflationary surtax proposal, Nixon instructed his aides to invite legislators who would cast crucial votes on both. “The President would like to have a heavy ‘sprinkling’ of the Senators who endorsed the ABM program and ‘four or five other Senators’” who were “marginal,” explained Special Assistant to the President Dwight Chapin. “In regard to House Members, he would like to have conservative Republicans – he said ‘some who have not been here previously and supported the surtax.’”

With the bulk of the seats reserved for administration officials and congressmen they might sway, the remaining few were precious political commodities. Potential campaign donors were always given preference. An early “action memo” to Colson ordered him to follow up on the “President’s request that you develop a list of rich people with strong religious interest to be invited to the White House church services.” At this, Colson had quick success. The guests for an ensuing East Room service, for instance, included the heads of AT&T, Bechtel, Chrysler, Continental Can, General Electric, General Motors, Goodyear, PepsiCo, Republic Steel and other leading corporations.

As the political purpose of the White House church services became obvious, criticism from the press increased. In July 1969, for instance, the Washington Post challenged the sincerity of this “White House Religion.” “Unfortunately, the way religion is being conducted these days – amid hand-picked politicians, reporters, cameras, guest-lists, staff spokesmen – has not only stirred needless controversy, but invited, rightly or not, the suspicion that religion has somehow become entangled (again needlessly) with politics,” the editors chided. “Kings, monarchs, and anyone else brash enough to try this have always sought to cajole, seduce or invite the clergy to support official policy – not necessarily by having them personally bless that policy, but by having the clergy on hand in a smiling and prominent way.” In the end, the Post gently suggested it might be best “to avoid using the White House as a church.”

Religious leaders began to denounce the East Room church services as well. Reinhold Niebuhr, once an outspoken critic of Spiritual Mobilization, now targeted its apparent heirs. For an August 1969 issue of Christianity and Crisis, the 77-year-old theologian penned a scathing critique titled “The King’s Chapel and the King’s Court.” The Founding Fathers expressly prohibited establishment of a national religion, he wrote, because they knew from experience that “a combination of religious sanctity and political power represents a heady mixture for status quo conservatism.” In creating a “kind of sanctuary” in the East Room, Nixon committed the very sin the Founders had sought to avoid. “By a curious combination of innocence and guile, he has circumvented the Bill of Rights’ first article,” Niebuhr charged. “Thus he has established a conforming religion by semi-officially inviting representatives of all the disestablished religions, of whose moral criticism we were [once] naturally so proud.” The “Nixon-Graham doctrine of the relation of religion to public morality and policy” neutered the critical functions of independent religion, he warned. “It is wonderful what a simple White House invitation will do to dull the critical faculties, thereby confirming the fears of the Founding Fathers.”

Despite criticism from liberal critics and the press – or perhaps because of it – the East Room church services continued for the remainder of Nixon’s term in office. According to social secretary Lucy Winchester, they were “the most popular thing we do in the White House.” “People don’t identify very well with state dinners, but they are familiar with prayer,” she noted on another occasion. “The honor of being able to pray with the President is something that they regard as special.” And, by all accounts, the East Room church services were immensely popular. “Congressmen have flooded the White House with the names of clergymen constituents wanting a turn in the Presidential pulpit,” the Wall Street Journal reported. “Hundreds of ministers have written directly, some enclosing photographs and programs of services they have conducted.”

Critics continued to scoff. “It gives the White House an unpleasant touch of Mission Inn,” Garry Wills wrote with disdain. But for many Americans – especially the ones whose support Nixon so avidly desired – there was nothing unpleasant about it, or the Mission Inn hotel and spa, for that matter. “And so they come,” a New York Times reporter noted in 1971, “not the poor and oppressed or the minorities that make for discomforting headlines, but the powerful in Washington and a healthy sprinkling of the people who put Mr. Nixon in office, and they sit around him, in worship of the Almighty.”

In many ways, the White House church services represented the climax of both the long postwar growth of religious nationalism in the United States and its process of partisan polarization. “Every president in American history had invoked the name and blessings of God during his inauguration address, and many … had made some notable public display of their putative piety,” religious scholar William Martin observed, “but none ever made such a conscious, calculating use of religion as a political instrument as did Richard Nixon.” Unlike prior presidents, who used a broadly-drawn public religion to unite Americans around a seemingly nonpartisan cause, the starkly conservative brand of faith and politics advanced by Nixon and Graham only drove them apart.

Kevin M. Kruse is a professor of history at Princeton University and the author of One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America, from which this excerpt was taken.