Universities face an existential crisis. A huge portion of the American public no longer sees their point or purpose. As a result, when the government slashes NIH funding, or cancels $400 million of contracts with Columbia, or forces the layoffs of two thousand workers at Johns Hopkins University, the broader public shrugs. Not their problem. They may even applaud a false sense of eliminating fraud. Another college closes every week, universities are freezing hiring, graduate admissions are cutting back or stopping altogether—and those who benefit from the work of higher ed do not understand why they should care.

I see various forms of response, but all of them seem aimed at the government. What I do not see is a shared campaign targeted at the public. We must return to the basics. We must explain the benefits of our work—not just for those who attend college, but for all.

Such a repositioning requires shifting the way universities present themselves. For many years now, colleges have argued that they are great places to get ahead. Want a higher income? Want power? Want a place of influence? Get a university degree.

Such advertising can understandably breed resentment in the 62 percent of Americans who do not have a college degree. Why should they care when the government takes aim at Columbia?

In focusing on individual consumers, universities have left unstated their importance for society. Many of those college graduates, like doctors and chemists and engineers, are presumably, hopefully, practicing their profession for the public good. Their work improves lives. We need them.

Which means that universities are not just for individuals. Universities are for all.

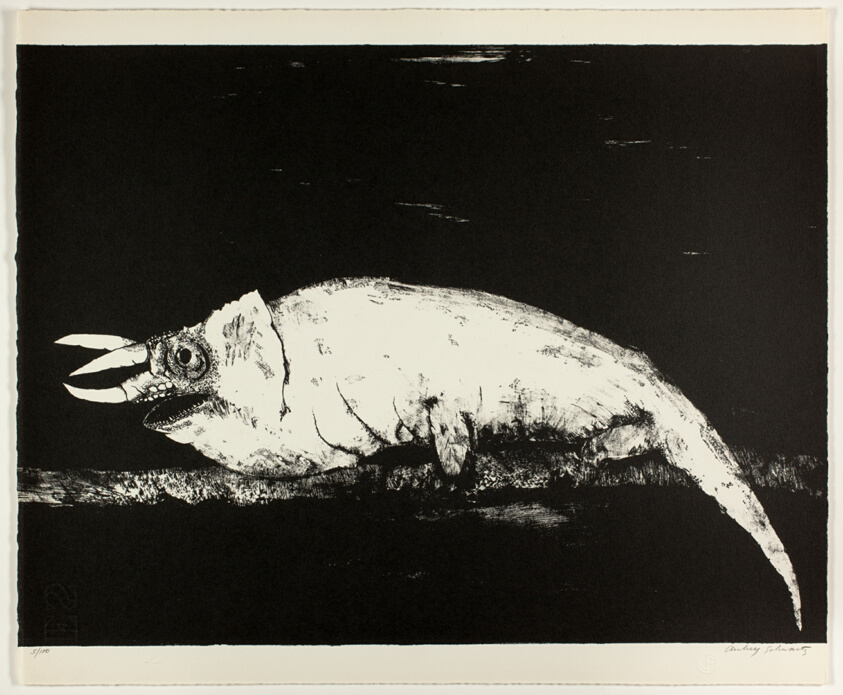

Consider the Gila monster. Studying the venom of this lizard may seem like just the sort of weird and esoteric research that taxpayers shouldn’t fund. Yet such research led to the development of diabetes medicine and weight loss drugs. It takes a university to study the Gila monster, but it requires no college degree to benefit. Research universities suffer from terrible PR, but here a solution presents itself: make an ad. Show the work.

Medicine is easy to pitch, but countless products flow from university research. Another lizard, the gecko, fascinates engineers. Geckos can generate incredible forces through their toe pads, hanging upside down and sticking to walls, yet they remove their pads without leaving any residue. Most human-made adhesives are either too hard to undo (like superglue) or leave a sticky mess (like duct tape). A branch of “gecko science” aims to build better adhesives. Universities enable the product, but the product is for all. Make an ad. Show the work.

How many agricultural advances have come from universities? Scientists at the University of Tennessee have helped develop soybeans that resist pathogens. You don’t need a college degree to eat soy. Others have innovated cotton crops that fight insects. Pick a dozen more agricultural advances. Are these seeds better than a generation ago? Is your equipment more advanced? Make an ad. Show the work.

Universities are not just for individuals. Universities are for all.

President Trump’s ability to attack universities depends in part on a public that does not understand the link between higher education and basic improvements in life. Imagine an ad that focuses on a single important bridge (pick any!). Who designed it? Where were they trained? What gave them the knowledge to build it? University education built the bridge, but no one needs a college degree to cross it. Make an ad. Show the work.

Infrastructure, health, clinical services, basic products—these are easy wins. But we could also advertise benefits most people, thankfully, do not need. The current chair of chemistry at my university is working out ways to detect chemical weapons without being exposed to them. Do we, as a country, want to uncover agents of chemical warfare without inhaling them? Most would say yes.

Defense technology will appeal to some, cultural amenities to others. In The Power Broker, Robert Caro explains that Robert Moses amassed enormous power because he built parks. Everyone loves parks. Moses made them and defended them, and the public supported him, despite whatever else he did, because he gave the people parks.

What else do people love? Zoos. Museums. Places to visit. Something to see, something to do. Guess what stands behind knowing how to nourish and conserve animals in the zoo? Guess what makes an art museum, a science center, botanical gardens, or the possibility of a play? Universities are for all.

For all that the sciences matter to the improvement of human life, the first federal grant for research was given for work in the humanities. The Founding Fathers, during the American Revolution, understood the importance of history. So they granted one thousand dollars to a man named Ebenezer Hazard to collect and publish important papers—to make an archive and save history from oblivion. The work was not for him; the work he did was for all.

The key is not to divide the public into two camps, those who have gone to college and those who haven’t. We badly need everyone. (My house is held together by a series of contractors with no college degrees.) The point, instead, is to tell people, those with college degrees and without, what universities are doing for the general good. The public gains from higher ed every single day, but they seldom link the benefits to the source. We need to make that link. We need to show our work. The problem with universities is not the content, but the communication.

Who will do this? One can imagine conferences pooling money for the project. They already do so for sports. The Big Ten and the SEC spend heaps of money every semester advertising their conference. They may want to set aside a small pot of money to explain why we need a university at all. Alabama, for example, will be one of the hardest hit states under the current proposed cuts to the NIH indirect costs; football fans there should perhaps worry about the decline of their state and whether or not it’s a hospitable place to study.

The problem with universities is not the content, but the communication.

Insofar as universities engage in marketing campaigns at present, they advertise primarily to consumers, not to the general public. Ads take two forms: My university is better than others and We have the best sports. Perhaps a few of these universities could band together for a shared campaign.

Private foundations and donors also might help. Those that grant funds for fellowships right now could pivot some of their money to explaining the importance of what we do. The public thinks of colleges and universities as elite other worlds with no effect on their daily lives. Yet universities have improved the lives of everyone, with or without a degree.

One effect of Trump’s campaign to “Make America Great Again” is that he is very good at showing what already has made America great—by attempting to destroy it. American universities are a wonder of the world. Republicans and Democrats have supported federal funding for decades. Long before that, the government invested in building and spreading universities from state to state, recognizing their fundamental importance to the nation. During the Revolution itself, Founders set aside time and money for archival research.

From the beginning, universities have made America great. An assault on American universities is an attack on American society. Universities are for all. Let’s make the ads. Let’s show the work.