When Bruce Springsteen released Nebraska in 1982—an album that is an excoriating journey into Springsteen’s past and the American psyche—he insisted that the record stand on its own: there were no tour dates, no interviews, no publicity press, just the album hitting the shelves. The fanfare has come now, four decades later. The renewed attention began with Warren Zanes’s 2023 book, Deliver Me from Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, which chronicles the improbable making of the record and how it fit into a complex turning point in Springsteen’s life, as he struggled to balance his rise to fame, his place in popular culture, his identity as an artist, and his emotions as a human being. Zanes’s book got made into the new movie of the same name, starring Jeremy Allen White as Springsteen, which in turn has prompted a four-disc re-release of the album, including outtakes and live versions of the songs on the album, as well as demos of songs recorded at the same time that found homes on other Springsteen albums, most notably Born in the U.S.A.

The new pile-on of media about Nebraska—the book, the movie, the re-release, and for that matter, the flurry of press reviews of all of the above—make clear that the album still has an enduring appeal. But in another way the layers of material and commentary are a peeling onion about the elusiveness of the material, and for that matter, the elusiveness of finding meaning in the darker things that happen in our minds and in the world. The book, movie, and re-release all reveal important facets of Nebraska, and how and why it arrived at its raw and final form. But each of them only get at a piece of the story. The rest gets away. This is fitting because Nebraska itself is like that: the songs are flashes of multiple, jagged emotional, cultural, and historical landscapes, glimpsed in the headlights from a speeding car at night. What you see might be hard to understand, but it’s also hard to forget.

Listen to the original record and it’s easy to understand why people are still interested in Nebraska. In an interview with Zanes in Deliver Me From Nowhere, Springsteen idly remarks that Nebraska might be his best album. He’s not alone in this opinion. Nebraska has an intensity that sets in from its first moments and never dissipates; before Springsteen starts singing, the music delivers a message. The title track that opens the album begins with an audible exhale, moving the reeds of a harmonica. For a split second, that long, lonesome whine, like a train, is all by itself. Then it’s joined by a quiet guitar. They’re together, but they sound lost, wandering across an empty space. The sonic landscape fits the desolation in the lyrics—a first-person narrative from Charles Starkweather, who, in November 1957, at the age of nineteen, shot a man to death before going on a killing spree across Nebraska and Wyoming with his fourteen-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate. Caught and convicted, Starkweather was executed by electric chair in 1959. Fugate went to prison as his accomplice and was released in 1976.

The Starkweather murders, ten in total, are marked by their senselessness; to read even a shallow account of them is to stare into an abyss of cruelty without motive. It’s a place where the question of why goes to die. In the lyrics, Springsteen latches onto this and never lets go. “I saw her standing on her front lawn / Just twirling her baton / Me and her went for a ride, sir / And ten innocent people died / From the town of Lincoln, Nebraska / With a sawed off .410 on my lap / Through to the badlands of Wyoming / I killed everything in my path,” he sings, with an eerie stillness. You listen and can’t help but ask why, and in choosing a first-person narrative, Springsteen dangles the wisp of a promise that he’s going to try to offer an answer. But he doesn’t. “I can’t say that I’m sorry / For the things that we done / At least for a little while, sir / Me and her we had us some fun,” he sings. The last two lines of the song make sure we understand. “They wanted to know why I did what I did / Well sir I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.”

Springsteen doesn’t leave room for much more to say about it. But the music picks up where words fail. The voice, the harmonica, the sparse, plucked strings, the open space: Springsteen didn’t invent that sound, and he knows it. It’s the sound of the early 1960s albums of his predecessor, Bob Dylan, to whom Springsteen was compared in the press (perhaps too breathlessly for either Dylan or Springsteen to buy it) right from Springsteen’s first album, 1973’s Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. But Dylan didn’t invent that sound, either. He got it most directly from folk legend Woody Guthrie, whose musical career spanned the 1930s and 1940s, and whom Dylan connected with in the last years of of Guthrie’s life, when Guthrie was confined to Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey, battling Huntington’s disease. But even Guthrie didn’t invent that sound all by himself. He learned from seminal folk and blues musician Huddle William Ledbetter, better known as Lead Belly; as Guthrie apparently told fellow folk musician Rambling Jack Elliot back in the 1960s, “if you want to learn something, just steal it—that’s the way I learned from Lead Belly.” Ledbetter, born in 1888, was himself a convicted murderer, sentenced in 1918 to do time at the Imperial Farm in Sugar Land, Texas, for killing a relative. He was pardoned in 1925—literally for a song, one he wrote to then–Texas governor Pat Neff asking for his freedom, having served his minimum sentence. Murder, theft, and music: all of them intertwine in murder ballads, which all of Springsteen’s musical ancestors wrote and performed. By writing “Nebraska,” and performing it and making it sound the way he did, Springsteen put himself in that tradition.

The layers of material and commentary are a peeling onion about the elusiveness of the material, and for that matter, the elusiveness of finding meaning in the darker things that happen in our minds and in the world.

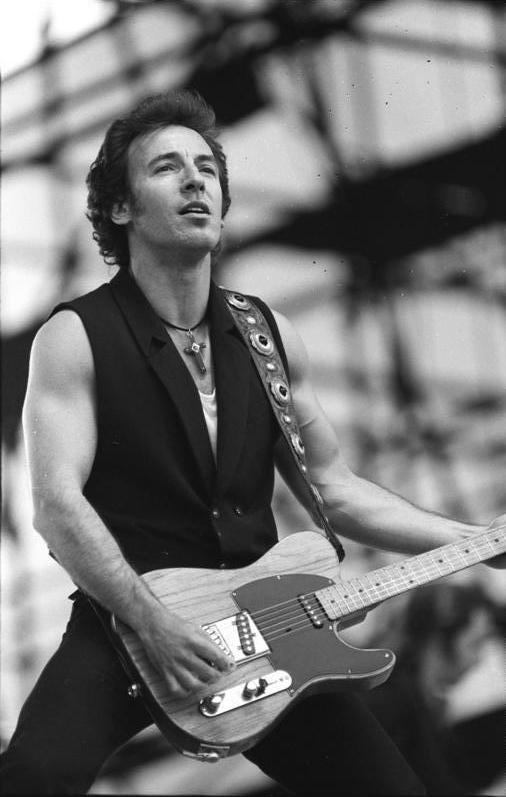

Bruce Springsteen, now seventy-six years old, is most often understood as a rock musician, for excellent reason. Of all the rockers still out there, Springsteen, with his juggernaut E Street Band, has been rocking about as hard and long as anyone. He has a string of bona fide rock classics that have burned themselves into the American musical consciousness, including a pretty astonishing decade-long run that begins with 1975’s Born to Run, proceeds through Darkness at the Edge of Town and The River, and culminates in 1984’s then chart-destroying behemoth Born in the U.S.A. His stadium shows are (apparently; this writer has never been to one) marathons of explosive energy.

But Springsteen, like many musicians, also demonstrates the limits of trying to understand even our most popular and scrutinized artists with a single frame. His discography of twenty-one studio albums also, by now, has a strong thread of much more intimate, and traditional American, music—Nebraska, The Ghost of Tom Joad, Devils and Dust, and The Seeger Sessions, along with numerous songs on other albums. In 2017 and 2018, he did a run of shows on Broadway in which he played solo on either guitar or piano. Springsteen is no stranger to folk music, and not just the commercial music that came out of the folk revival of the 1960s and morphed into the singer-songwriter genre that persists today. He knows about the traditional music that lies beneath it and to some extent all American music—the stuff cultural writer Greil Marcus called the Old Weird America, a stew of blues, country, gospel, fiddle music, and work and play songs that has always nourished American culture, even as it embodies its darkest, gnarliest corners.

If rock music is often about the assertion of the individual and the primacy of the here and now, folk music is often about the nameless collective and the understanding of a deep connection to the past. Nebraska and the story behind it embody both. Zanes sheds a lot of light on Nebraska by understanding it as rock music, and by focusing on Springsteen as a singular artist wrestling with himself and his growing fame. Viewing it as folk music, however, offers answers as to why that individual story continues to resonate—why we’re returning to it forty-three years after it was made, and taking another plunge into the unanswerable questions behind the violence and desperation that Springsteen, like many before and after him, understood as part of what makes this country run.

Zanes’s placement of Springsteen within the frame and history of rock music is the right angle for telling how Nebraska got made, and appreciating how improbable it really was. Zanes is in a position to know. Starting at seventeen, he was in a recording and touring rock band, the Del Fuegos, that in the 1980s opened for INXS, ZZ Top, X, and Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. He also became an academic, getting a Ph.D. in visual and cultural studies from the University of Rochester. He now teaches at New York University, and Deliver Me from Nowhere is his fifth book about popular music. All of this experience comes to bear. He writes with the verve of someone who was there, once sharing a stage with Springsteen and certainly sharing the lifestyle. When talking about the album itself, the energy of his sentences conveys his love for the music. But he’s also clear-eyed enough to take a step back and just tell the story, which, even in its bare-bones version, carries the aura of lore, and the keen sense that we’re lucky to have heard this album at all.

As Zanes tells it, Springsteen recorded Nebraska—mostly in one night in early January 1982—in the bedroom of a rented house in suburban New Jersey, on a then-new piece of recording equipment, a tape machine that allowed people to record multiple tracks onto a regular old cassette. One other person was present, a recording engineer. Springsteen did it this way because he was interested in exploring the atmosphere of the new songs he was writing fresh off the tour in support of The River. He cared enough about their sound quality to do a little multitracking (a couple songs include overdubs of other instruments) and to add some echo to the proceedings. But he didn’t imagine he was making a finished product; he intended to bring the cassette to rehearsal for the E Street Band to hear, whereupon the band would work up arrangements to flesh out the songs. Springsteen was so unsure of the original tracks that for a couple weeks he carried the tape around in his pocket without even a case. It felt disposable to him, until suddenly it didn’t. As Springsteen told Zanes, “I went into the studio, brought in the band to rerecord and mix those songs, and succeeded in making the whole thing worse.” Even a cursory listen to the recently released electric versions, part of the 4-disc reissue, reveals that Springsteen is right.

Part of the reason it got worse was that “the characters got lost.” But it was also about the overall feel. “I just had a certain tone in mind, which I felt was the tone of what it was like when I was a kid growing up. And at the same time it felt like the tone of what the country was like at the time.” With the whole band, that tone vanished. Zanes notes that the recording sessions weren’t unproductive: several of the songs ended up on Born in the U.S.A., including its title track. But the ten songs on Nebraska eluded them. Springsteen wanted an album of them, and he had them on that linty cassette. As Springsteen tells Zanes, “I pulled them out of my pocket one day and said, ‘I think this is it.’” And it is. Overcoming some technical limitations, the cassette was mastered to become a record, and that was that.

For Zanes, this unusual lineage made Nebraska simultaneously an anomaly and a harbinger of things to come. “Nebraska was unfinished, imperfect, delivered into a world hovering at the threshold of the digital, when technology would allow recorded music to hang itself on perfect time, carry perfect pitch, but also risk losing its connection to the unfixed and unfixable,” Zanes writes. But it was also a glimpse into the future of people recording things at home, a future we live in now. As The National’s lead singer, Matt Berninger, puts it, “I think Nebraska was the big bang of the indie rock that was about making shit alone in your bedroom.”

The book is at its richest when it puts the album in its contemporary context, showing how Springsteen made it during a tumultuous moment in popular culture that dovetailed with his own turmoil about his place in it. In hindsight, the 1980s were the last time popular culture produced a series of megastars, artists who could dominate the cultural conversation for months at a time, whose work could seem inescapable. Taylor Swift is the closest thing we have to that now, but there’s only one of her. In the mid-1980s, there were four: Michael Jackson, Prince, Madonna, and Springsteen. But while Springsteen was making Nebraska, his star was still on the rise. He hadn’t taken his place in the firmament yet, and Zanes shows that he had intensely mixed feelings about what lay in store for him, what superstardom would mean for him as an artist and as a human being. As Springsteen’s longtime manager Jon Landau told Zanes, Nebraska was “part of the story” of “his fears about if he became so big, would it invalidate or contradict his identity as an artist? Would he become a pop star and have people lose the focus on his deepest talent?” Who would he be if he got too famous?

“Nebraska was unfinished, imperfect, delivered into a world hovering at the threshold of the digital, when technology would allow recorded music to hang itself on perfect time, carry perfect pitch, but also risk losing its connection to the unfixed and unfixable.”

Almost subliminally in Deliver Me from Nowhere, there is the sense that Springsteen knew that he had to get his own emotional baggage in order before he could handle the spotlights waiting for him. As open as he is with Zanes, Springsteen doesn’t seem to speculate on this very much with him, though other sources, including Springsteen’s autobiography, relate that Springsteen suffered a bout of severe depression. He wrote, recorded, and released the songs on Nebraska in the midst of it, then went on a road trip across the country, had a breakdown, and moved into a new house in Los Angeles.

Zanes ties the threads of the book together in a way that Springsteen himself doesn’t. In the songs, Springsteen reached back through the American folk songwriting tradition to explore his own personal history, his childhood with his parents and grandparents, a hidden world where things were darker, more complex, and more desperate than they seemed, and explanations, morals, and meanings didn’t come easy. “I often go back to that place in my dreams, and it’s still a place that holds a lot of significance for me, a lot of emotion,” Springsteen tells Zanes. “I pass by it a lot, still. It’s a very mysterious place.” Nebraska, writes Zanes, “was a place Springsteen could go when he needed to remember where he came from.” He got it all down in verse, in all its elusiveness, recorded and released it without compromising a shred of his vision, took off for a while, and then two years later turned around and embraced his destiny to become a superstar.

Where Zanes’s book creates a black box around Springsteen’s depression, the movie Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere opens that box right up to create, mixed reviews notwithstanding, one of the best music biopics out there. Springsteen separates itself from the pack in part by sticking to the source material. By focusing on a specific, crucial turning point in Springsteen’s life rather than trying to cover it all, the film avoids the usual traps that biopics fall into. After all, the dirty somewhat-secret for most successful artists is that, once they become successful, their lives aren’t very interesting, unless they do something to screw it all up (which Springsteen hasn’t). Rather, as with superheroes, the most intriguing part of an artist’s biography is the origin story: their lives before they became working artists, their childhoods, adolescence, and early adulthood. We want glimpses into the experiences that shaped them into the artists they became. We want to see the first glimmers of talent, the path of their ascent, artistically and commercially. For a conventional biopic, a natural stopping point—though none of the ones I’ve seen actually stop there, and suffer for it—would be the moment of their big break.

But Springsteen isn’t conventional. In dramatizing the making of a single album, it unsticks itself in time, hopping back and forth between 1981–82 and the mid-1950s, when Springsteen was a child. The 1980s parts of the movie deftly capture Springsteen rising from fame to superstardom, focusing on just how destabilizing the speed of his upward trajectory felt. At the end of the River tour, he returns to the places where he cut his teeth as a musician and performer, but learns fast that the life he had there is gone. Now, when he sits in with his friends’ bands at the Stone Pony, it’s a cameo by a local celebrity. He gets a girlfriend without even trying. The film is especially good at tracking, with a few key details, the double-edged sword of his growing notoriety. He can still walk around on the street in New York, go out to eat at a diner, but a handful of people are starting to recognize him, and even a shout from a taxicab (“‘Hungry Heart’!”) feels like both an affirmation and a wrecking ball to his private life and sense of self. The house he rents in New Jersey isn’t fancy and could be a place of solace, but instead—until he records Nebraska there—he rattles around in it like a caged tiger. The sense of unfinished emotional business that Zanes’s book alludes to is front and center, especially due to the excellent decision to cast Jeremy Allen White (The Bear), an actor with a serious gift for conveying emotional turmoil without saying a word or moving a muscle. White’s empathic, complex depiction is utterly believable (and given Springsteen’s heavy involvement in the film, probably at least mildly accurate), a portrait of a young man who only really knows what he’s doing when he’s making music. Otherwise, he’s lost. The movie gives us a reason why.

Springsteen’s return to his pre-fame haunts also gives him the occasion to revisit the places of his childhood, which, as seen in vivid black-and-white flashbacks, was a time of isolation, poverty, and casual brutality. It’s only a handful of scenes, but the cast of three characters—mother Adele (Gaby Hoffmann), father Douglas (Stephen Graham), and a young Bruce (Matthew Anthony Pellicano Jr.)—leaves an indelible mark. Springsteen writes in Born to Run that “my mom and pops were bound by an unknowable thread. They’d made their deal a long time ago; she had her man who wouldn’t leave and he had his gal who couldn’t leave. Those were the rules and they superseded all others, even motherhood.” Hoffmann and Graham get this across adeptly, but the scenes really shine in depicting the toxic, binding chemistry between Douglas and Bruce. Douglas comes across a man broken long before his son ever arrived. Somewhere in his rage and pain and the miasma of alcohol, he wants to be a good father, but has no idea how. He has it in his head that Bruce should be tough. Bruce doesn’t want to be tough, but he doesn’t want to disappoint his father, either. We’re treated to a scene that isn’t overtly violent but feels like it, in which a drunk Douglas lurches into young Bruce’s room, trying to get Bruce to practice boxing with him, to get the kid to hit hard. Bruce doesn’t want to do it: he doesn’t want to hit his father, maybe in part because he’s afraid of what his father will do if he lands one that hurts. It only gets worse from there. As the movie implies, the wound in Springsteen goes deep. A couple decades of growing and years of hard work in music later, he still can’t escape it. In the logic of the movie, the implication is that he knows he has to confront it all, learn who he is all over again, before he hits the really big time, or fame will destroy him. But he doesn’t know where to start.

In the movie more than the book, Springsteen’s biggest helper—personally, artistically, and professionally—is manager Jon Landau, played with such quirky precision by Jeremy Strong that I went home and looked up an interview with Landau just to see if he really talks like that (he does!). It’s been said a lot that a band can be a surrogate family, but in Springsteen, the E Street Band makes only the smallest of appearances, either playing or recording, and the roles are almost non-speaking parts. Instead, Landau, and Landau alone, is the closest thing to a family Springsteen has. He’s a brother and a father. He’s a confidante to Bruce in sharing his artistic journey. He’s a protector, shielding Springsteen from the record executives who just want another hit and want it now. And in the end, Landau’s the one who gets through to Springsteen that he can’t and shouldn’t have to face his past alone. In a movie full of gently touching scenes, the most affecting is one in which Landau visits Springsteen in his rented house; they’ve finished the album, but Springsteen is still spiraling. Landau stops talking. He puts on a tape of Sam Cooke’s “Last Mile of the Way,” and the two of them sit side by side—a moment of familial physical tenderness that, it’s possible, Bruce never had when he was a kid.

The choice of song is subtle and suitable. Cooke recorded “Last Mile of the Way” in 1955, when he was still in the Soul Stirrers, still a straight-ahead gospel singer. “You Send Me,” his breakout hit, was two years off, but especially in hindsight, had the same kind of inevitability that Springsteen had in 1982. Cooke went on to be a pop superstar and civil rights leader. He also met his end in 1964 at the age of thirty-three, killed in a shooting at a $3 L.A. motel, for which the official story doesn’t seem to totally add up. If he’d never gotten famous, maybe he would have lived a little longer.

Nebraska’s ability to connect with a modern audience isn’t about the backstory; many who discover the album today don’t and won’t know anything about the circumstances under which it was made. The songs on the record give no indication that any of the details are autobiographical or intended to be understood that way; if anything they suggest the opposite. The distancing starts right away with the geography of the songs on the album, ranging from Nebraska to Chicago to New Jersey. Where Springsteen is drawing from his own experiences in telling those stories, he’s doing that not to reveal something about himself, but to connect with a more general American experience, “the tone of what the country was like,” as he put it. Or, as Zanes quotes musician Patti Griffith, Nebraska is about “violence,” “how America has struggled to find its soul, has never had much of an identity beyond the brand that’s been sold over and over again to people living here. But lives are lived behind the brand, and Springsteen is unearthing them, exposing them to the light.”

Griffith is pointing at a theme much larger than what Springsteen was going through personally, or where the country was at the beginning of the 1980s. Nebraska is now forty-three years in the past—comfortably further back than Dylan was from Springsteen, or Guthrie from Dylan, or Leadbelly from Guthrie. It’s further back in time from us now than the folk revival of the 1960s was from the blues and country music it was resuscitating. Musicians then felt they were digging up from an almost forgotten past. The internet has made that kind of scarcity almost impossible; music that used to require a drive to the end of a dirt road in Appalachia to obtain is now just a Google search away. But with the passing of two generations between Nebraska and now, it’s fair to think of it as part of that folk lineage. Springsteen’s songs of murder, family, and hard luck may not have cracked the American code, but he joins in a long parade of people who have tried, and maybe that’s the tradition. Violence has shot through the heart of the American enterprise from the beginning, and for as long, people have been singing about it. The records show we’re no closer to understanding it. But it has sure made for some timeless songs along the way.