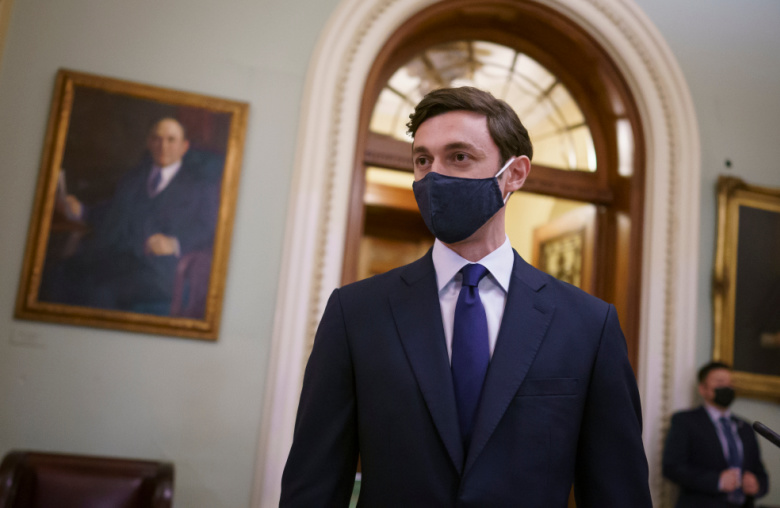

On January 20, after new Georgia Senator Jon Ossoff was sworn in, he tweeted that he had carried in his jacket pocket copies of the 1911 and 1913 manifests of ships on which his great-grandparents had arrived at Ellis Island. Ossoff’s photocopies were more than good luck charms. He used them as a religious artifact—“a totem,” as the Jewish Telegraphic Agency described it—that helped him reflect on his place in the world through an emotional connection to his heritage. His nostalgic relationship to his family history is in line with the way many Jews and other Americans tell stories about their place in the world.

In my new book Beyond the Synagogue: Jewish Nostalgia as Religious Practice, I examine the materials and institutions through which American Jews engage, promote, and teach nostalgia for the immigration of Ashkenazi Jews from Central and Eastern Europe to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. This is the history of the majority—though certainly not all—of American Jewish families, including Ossoff’s. Nostalgia for the mainstream story of Eastern European origins and early-twentieth-century American Jewish immigrant experiences has become a prominent part of American Jewish religion from the 1970s to the present day. I look at case studies of the materials and institutions of Jewish genealogists, historic synagogues used as museums, children’s books and dolls, and artisanal delis and other Jewish food sites, and find that they are best understood as part of American Jewish religion. Just like many other religious activities, these practices of Jewish nostalgia teach individuals to place themselves in community-defined stories about the past and shared values.

In fact, beyond Ossoff’s photocopies of ships’ manifests, nostalgia has been in the headlines a great deal lately. During the pandemic, nostalgia—a sentimental longing for the past that cannot be fulfilled—has seemed to offer a particular comfort. In this fearful time, we have cozied up with our favorite childhood movies, television shows, games, music, and books for comfort. It has been easy to poke fun at the enormous spike in baking bread and crafting and, especially, the resulting shortages of flour and yeast. But the turn toward the comfort of home-based practices that evoke a longing for seemingly simpler times is not truly funny. We need soothing distractions in the midst of terror, and these items help us tell stories about ourselves.

At the same time, the Trump era has been rife with denunciations of nostalgia. Liberal pundits were—rightfully—quick to critique the nostalgia suggested in Trump’s 2016 slogan, “Make America Great Again.” They have reminded us that the mid-century United States was not that great for many Americans, including most women, people of color, LGBTQ+ folks, and others. Even worse, Trump and his supporters embraced symbols of white supremacy and the Lost Cause. Opponents denounced nostalgia for the Confederacy and the antebellum South. Following the August 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville—itself a reaction to Charlottesville’s proposed removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee—and again after George Floyd’s death in 2020, announcements that Confederate statues would be taken down came quickly. These rejections of harmful forms of institutionalized nostalgia have focused on the public spaces we share.

In popular discourse, then, there is a disconnect between the embrace of individual and family-based nostalgia and a repudiation of institutional and civic-oriented nostalgia. But nostalgia itself cannot be neatly divided into good and bad forms. Nostalgia is both an emotion and a practice, and it is never value neutral. It connects individuals and families to broader communities through particular, mainstream narratives about the past. It is rife with values which can be good, bad, or a complicated mix, depending on what values it reflects and who is included and excluded from its narratives. In connecting us emotionally to the past, it helps us understand our present and directs values for the future.

Nostalgia helps us understand ourselves and our families in the context of broader communal stories. When Noah Bernamoff founded Mile End Deli, a Jewish deli in Brooklyn that reframes Ashkenazi American cuisine using sustainable ingredients and dishes made in-house, he named his restaurant after the Jewish immigrant neighborhood in Montreal, his hometown. Originally, Bernamoff intended to serve Montreal cuisine. But, as he writes in The Mile End Cookbook, his vision changed to reflect a different aspect of his family history when his grandmother died:

This woman was the glue that held my family together … Her food, and her huge Friday-night dinners, gave structure and substance to our lives … Maybe I overreacted, but when she died I thought to myself: Is this the end? Will this food find someplace to live on in our lives? Suddenly everything shifted into focus. This restaurant we were about to open had to be a Jewish restaurant.

Bernamoff’s rhetorical questions are not only reflections about his own family, but also imply broader concerns about the passing of the first and second generation of North American Jews. His own family history stands in for the broader story of North American Jewry. It provides a model for customers and cookbook readers to understand their family histories as connected to broader narratives, too.

This kind of nostalgia, I find, functions as religion for many American Jews. Religion is best understood as meaningful relationships and the practices, narratives, and emotions that create and support these relationships. Religious studies scholar Robert Orsi defines religion as networks of relationships among the living, between the living and the dead, or between humans and the divine, each of which may be highlighted to varying degrees in different contexts. Understanding religion as relationships and structures recognizes the ways that families, communities, and memory are central to religious activity. Viewing relationships as central to religion allows us to see how individuals who do not regard themselves as “religious” make meaning in their lives, as well as how those who do see themselves as religious find meaning outside of traditional practices, guided by a variety of supposedly secular institutions and materials.

Like religion, nostalgia is a term that is often taken for granted but that has a complicated history. Scholars and cultural critics frequently deride both nostalgia and the related concept of sentimentality. They dismiss both as inauthentic, readymade feelings as opposed to genuine reactions to one’s circumstances. At their worst, nostalgia and sentimentality may be considered dangerous because they permit the absence of critical thinking and the abdication of personal responsibility. “Longing for the past and fear of the future inhibit the experiments and innovations that drive progress,” writes cultural critic Johan Norberg. Christian theologian Jeremy Sabella describes nostalgia as “spiritually corrosive,” a distraction from the blessings and challenges of the present.

In contrast, I argue that nostalgia is not merely reductive; it can also be productive. It reduces complicated histories to an accessible narrative, but it also produces personal and communal meaning. Nostalgia fulfills individuals’ search for an authentic past, creating communal cohesion through shared religious affect and consumption. While academics and critics have disparaged nostalgia for its emphasis on exaggerated emotion, it is, in fact, a way of finding one’s place in the world and of laying claim to the past. The institutions of nostalgia encourage their patrons to claim ancestral heritages in ways that are meaningful beyond simplistic divisions among religion, spirituality, and culture.

To understand nostalgia, we need to take seriously the feminist adage, “the personal is political.” Feminists in the 1960s used this phrase to insist on the importance of “women’s issues,” often dismissed as merely personal or inconsequential. Emotions, too, are political. Individuals’ emotions and their embodied experiences are closely connected to public life, communities, and civic bodies. Identifying “public feelings”—shared emotions that connect us to broader narratives—like nostalgia highlights the connections between how individuals make and find meaning in their own lives and how communal institutions guide the emotions that we share.

Looking at nostalgia teaches us that emotion and careful historical research need not be mutually opposed. Many of the people I write about are accomplished researchers of the past who thoughtfully retell historical stories for public or familial consumption, though they sometimes do so differently than academic historians do.

For instance, genealogist Manny Hillman writes in the Jewish genealogy journal Avotaynu that he had always been told that his father was born in Graz, Austria. When Hillman found documentation that his father had emigrated from Jerusalem, his father eventually admitted that he had grown up in an orphanage in Jerusalem, visiting his impoverished, widowed mother on weekends. He had invented an alternative personal history, perhaps as a way to avoid uncomfortable questions about a traumatic childhood. An experienced researcher, Hillman advises other genealogists to think critically about both documents and family legends. Nonetheless, when his father died, he listed Graz on his father’s death certificate “as a tribute to that part of his life that obviously had troubled him.” Hillman offers an ethical model of honoring the stories that have shaped others’ lives, regardless of their factual accuracy. For Hillman, virtue is not to uncover and share facts but also to honor what has held emotional significance for others and what continues to inspire sentimental meaning for us. Nostalgia helps us recognize the importance of our emotional ties to family and community histories and the ways in which what we owe to the past is not always straightforward.

Nostalgia is a norm, and as such it encourages the most simplistic, streamlined versions of any story. The nostalgic longing of American Jews for stories of Eastern European immigration at the turn of the century and for Eastern European pasts deliberately centers certain Ashkenazi experiences and marginalizes other Jewish stories. American Jewish genealogists may find they have diverse backgrounds, but many, I have found, are drawn to family stories of Eastern European immigrants that fit the dominant narrative.

Standardization narrows the stories told about American Jews, but, paradoxically, it also expands who can engage with them. The story of American Jewish pasts has become expansive enough to encompass and include those whose family histories do not match the narrative—one does not have to be descended from New York Jews, or even be Jewish, to connect meaningfully and emotionally to the past by eating a corned-beef Reuben sandwich at Mile End Deli or reading a children’s book about Eastern European Jewish immigration.

At the same time, the standardization of nostalgia for Eastern European Jewish heritage and its increased popularity necessarily marginalizes the communal and familial histories of Jews who are converts to Judaism or who do not descend from Eastern European immigrants. Some deli restaurateurs incorporate dishes from the cuisines of Sephardi and Mizrachi Jews (Jews of Spanish or Portuguese descent and Middle Eastern Jews) into their menus, but these are generally side dishes that do not distract from the Eastern European-focused nostalgia that propels their enterprises. For better or worse, mainstream Eastern European Jewish nostalgia can incorporate stories that deviate from the standard narrative without losing the magnetic power of its central story. Nostalgic stories and practices can ignore or even erase histories beyond their boundaries. Those who wish to create other avenues of history and heritage have to work twice as hard to create alternative narratives.

The events of the last few years have demonstrated that we have an obligation to carefully choose what narratives we want to honor. Recognizing nostalgia as a norm that connects families and communities to larger, institutionalized narratives helps us think about the ways in which the personal is political and the political is personal. Nostalgia is not merely good or bad, but a bridge between historical scholarship and social memory that makes the past meaningful in the present. Acknowledging the ways in which it functions as an emotional norm can allow us to take pleasure in the ways individual histories connect to broader histories and help us to acknowledge the gaps in those stories, making room for new ones.

Rachel B. Gross is assistant professor and the John and Marcia Goldman Chair in American Jewish Studies in the Department of Jewish Studies at San Francisco State University. She is the author of Beyond the Synagogue: Jewish Nostalgia as Religious Practice.