As a Baptist minister who wants to talk about Islamophobia—indeed, feels called to talk about Islamophobia—I always search for hard evidence. I want to help fellow Christians understand that I’m talking about more than anecdotes, and more than vibes. And one of the best-regarded instruments for measuring systemic Islamophobia is the National American Islamophobia Index, which was introduced in 2018 by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. Using five question, the Islamophobia Index measures “public endorsement of five anti-Muslim tropes” related to Muslims’ alleged propensity for violence, discrimination against women, hostility to the United States, lack of civilization compared to other people, and responsibility for acts of violence committed by other Muslims.

The results of the 2025 survey are alarming. Compared with 2022, the overall Islamophobia Index has increased by 8 points, from 25 to 33. The sharpest increase was observed among white evangelicals (15 points), Catholics (12 points), and Protestants (7 points). Minimal increase was recorded among Jews (from 17 to 19 points) and the nonaffiliated (from 22 to 23 points). This distribution shows clearly that Christians of all stripes were the driver of the Islamophobia Index increase in the last three years.

This lengthy history of Christian anti-Muslim hostility, as well as the fact that Islamophobia thrives in many American churches today, requires of contemporary American Christians a consideration of our ethical and theological responsibilities toward our Muslim siblings. In my book Challenging Islamophobia in the Church: Liturgical Tools for Justice (Judson Press, 2026), co-authored with Michael Woolf, I argue that, for Christians, learning about Islam and engaging with Muslim communities is a necessary endeavor, not just because of the troubling history of Christian Islamophobia, but, more important, because knowledge of Islam can make one a better (and more educated) Christian.

For example, most Christians, asked about the nature of the Trinity, tend to resort to insider-speak or wave it off as a “mystery.” However, Christians who are familiar with Muslim theological critiques of the Trinity will be able to produce a deeper and more articulate explanation of this doctrine. Engagement with the tenets of Islam in Christian religious spaces does not mean that one’s faith will be diluted; rather, it may lead to formulating new theological insights that produce “holy envy” for Islam’s strengths, while preserving Christianity’s unique commitments. Theological conversations between the Christian and Islamic theologies have been taking place since late antiquity. While for a long time they were polemical in nature, today the goal should be looking for mutual understanding, rather than discrediting each other. After all, one cannot respect something one does not know.

This lengthy history of Christian anti-Muslim hostility, as well as the fact that Islamophobia thrives in many American churches today, requires of contemporary American Christians a consideration of our ethical and theological responsibilities toward our Muslim siblings.

With that in mind, Christian clergy may also wish to integrate the wisdom of Islamic scriptures in their liturgy. I have developed a program that follows the liturgical calendar, the Lectionary, and suggests passages from the Qur’an and from the Hadith (a vast body of narratives about the life and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) that are resonant with the Lectionary themes.

For example, instead of the Christian narrative of the birth of Jesus, why not offer the Qur’anic recounting of this story in ways that are both similar and different from the Christian one? The Muslim Jesus, known as Isa, is not God incarnate but a highly venerated prophet. As in Christianity, he comes into the world through virgin birth, through God’s command alone. The pregnancy is announced to Mary (Maryam) by God’s angelic messenger, often identified by classical commentators as Gabriel (Jibril). In the Christian version, Mary’s innocence is defended by Joseph, while in the Muslim narrative, it is newborn Jesus himself who speaks from the cradle to praise her chastity. Jesus’ virgin birth and his ability to speak as a newborn are considered miracles by Muslims. In both traditions, God’s mercy for humanity is revealed in sending Jesus. The Muslim belief in the miraculous nature of Jesus’ birth and his prophethood is also an important highlight. Islam’s rejection of Jesus’ divinity does not diminish the respect with which he is treated by Muslims.

There is more to this event than just looking at a familiar story through a different sacred lens. The Islamic narrative has a distinct social justice aspect. Fearing people’s condemnation, pregnant Mary withdrew from her community. When the time came, she labored alone, under a palm tree, and God provided her with shade, water, and dates to ease her suffering. What Christians can take away from this version of the story is Islam’s commitment to protecting the vulnerable, especially women, and its uplifting of divine compassion for outcasts from society.

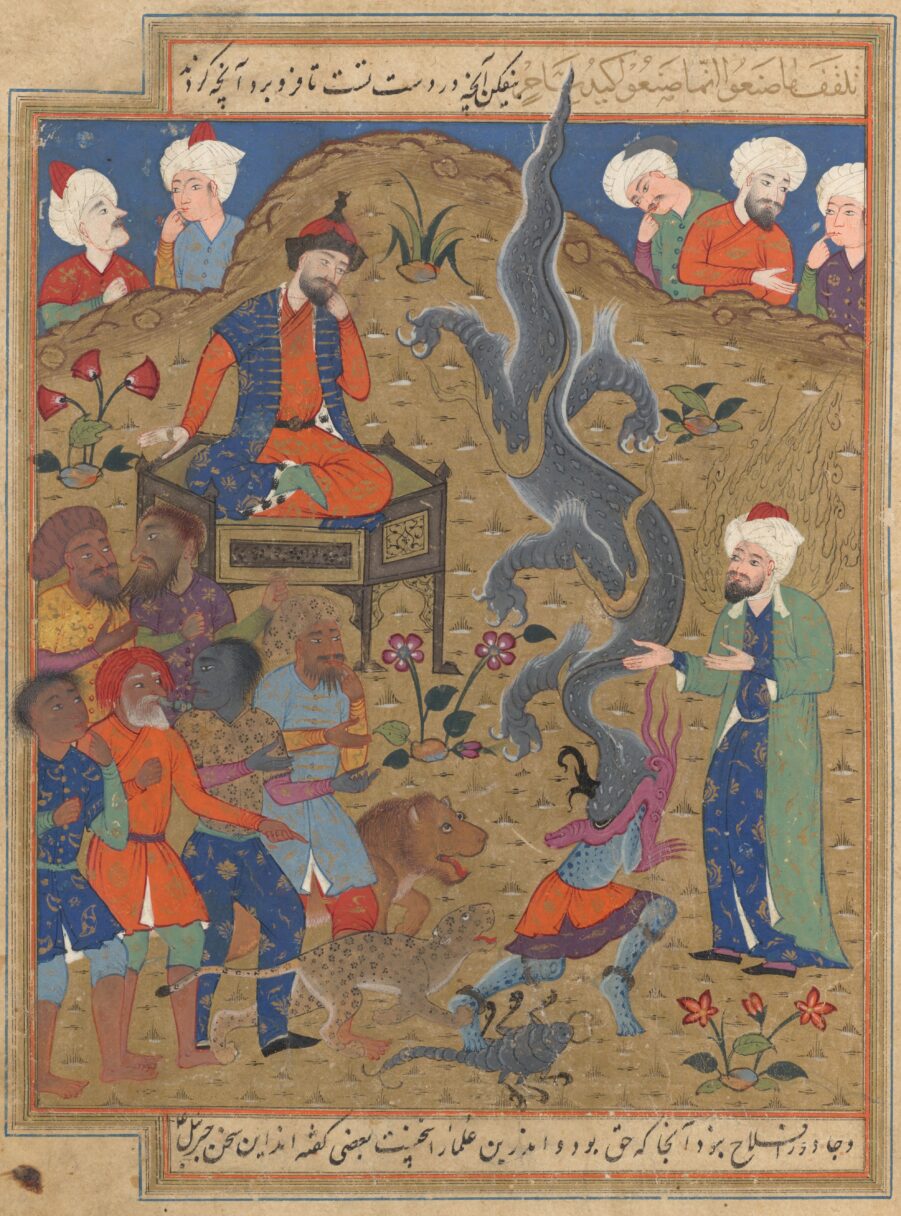

It can be intriguing to Christians that Moses’ (Musa’s) story is remarkably similar in the Bible and the Qur’an: both include Pharaoh’s order to murder Hebrew male infants, Moses’ deliverance as he floats down the river and is rescued by a female relative of the Pharaoh, his upbringing at the royal court, his killing of an Egyptian, his escape, his prophetic call at the burning bush, his challenge of the Pharaoh, the Exodus, and the revelation of the Torah (Tawrah). One of the more moving aspects of the Qur’anic narrative of Moses illustrates God’s response to fear: God does not simply ignore Moses’ fear when the staff turns into a snake (this event is described in a more dramatic way in the Qur’an), but gently shepherds him through it, proclaiming, “You are perfectly secure.” The wisdom we can derive from this passage is that God does not overlook our fears but instead lends us the courage to face them.

Christians may be unaware that Islam sends humanity a message about the environment. Like Christianity, Islam emphasizes that humans are stewards, not owners of the Creation. Both traditions focus on responsible care, not destruction of it. The Prophet Muhammad is recorded to have said, “Safeguard the earth, for it is your mother who will report (to God) the good or evil anyone does on it.” This warning has a special resonance at a time when trees are felled on a massive scale for agricultural expansion and infrastructure development, when many plant and animal species go extinct every year, and when oceans, soil, and air are being polluted in countless ways. Drawing from the Hadith while preaching about the environment can make the conversation truly global: whether Christian or Muslim, from the global North or global South, this is our world to share.

Islamic scriptures offer universal wisdom to Christians in both their similarities and differences. This is a message I am spreading across Chicagoland, where I live and serve, through the initiative Reading the Qur’an in Churches. It connects Christian and Muslim congregations by organizing recitations and readings of the Qur’an by Muslims in Christian spaces, followed by sessions during which Christians can ask questions about Islam. The Christians are usually very grateful for the opportunity to unlearn the anti-Muslim stereotypes that infuse our public spaces.

With Christian nationalism on the rise, challenging Islamophobia is an urgent need. The data is clear—Christians have work to do. Our faith has a troubling record when it comes to coexisting with other traditions, and the best way of addressing it is to acknowledge that and try to do better as Christians. Challenging Islamophobia should be an expression of our Christian witness, not a concession that is made to a minority group.