I live in a country dreamt up by mystics and seers and built by generals and politicians. It has been more than a century since the illegal settlements—homes with red-tiled roofs, villages surrounded by fortified fences, towns featured on newscasts from Delhi to London, from Washington to Beijing, that define the reality of Israel and Palestine—were prayed for in a small attic in Jerusalem by the great rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and his disciples; it has been fifty years since the founding of the Gush Emunim movement, which was responsible for the construction of most of the settlements, and was the primary source for the settler movement on land conquered in the Six Day War. And it has been just over forty years since my parents—the children of European immigrants, and educated students of literature and history—moved me and my siblings to a small lean-to in a settlement outside the city of Ramallah.

My life in the settlement existed close to nature but behind fences, a tightknit social system alienated from the neighboring Palestinian population. There was a sense of security within the settlement’s boundaries, and a lack of criminal activity among the Jews living there. There was, however, a sense of danger, from shooting attacks and Molotov cocktails coming from outside of the settlements, or as soon as one left.

I remember traveling by car one morning with my family to Jerusalem. I was still a boy, and the road took us through Ramallah—this was before bypass roads had been constructed. Avraham Fried, the haredi singer we loved, was on the radio, crooning, “Once I went inside to offer incense.” Immediately after a sharp bend in the road, under one of the white bridges, stones were thrown at our car. The stone-throwers, their faces covered, fled into the maze of alleys. The gentle, melancholic music was cut off by the stones’ impact and the slamming of the door, as my father stopped and got out of the car, his gun drawn. He chased the stone throwers and returned after a few minutes, his gun still drawn, panting.

The distances we covered every morning wrenched us away from the settlement’s harmonious landscape and the tranquility of the bare hills. Before that bend in the road, we still passed along a few streets that offered us an illusion of neighborliness. I think we were curious and wanted, deep within our small bodies, to get closer to the vendors in front of the mosque. It never happened.

We could get closer to our soldiers, though. The military base that stood to the right of the entrance to the settlement, housing the soldiers who protected it, was central to our lives. It was a gateway to another world, a place symbolizing the militaristic orders of adulthood that awaited us, and the distant realities of Israeli society. On Sabbath afternoons, we would go in groups to the base to ask the soldiers the results of the Saturday soccer games. What was the score? We chased after the tired and bored soldiers with these questions. They laughed, probably surprised, likely embarrassed in the face of children wearing white kippahs and white shirts, black pants and sandals, with sidelocks, sweating in the hot sun and wanting to know whether Beitar Jerusalem had won. But when we asked about the soccer games, which took place on the Sabbath, we were really asking about what lay beyond the settlement’s fences.

My father stopped and got out of the car, his gun drawn. He chased the stone throwers and returned after a few minutes, his gun still drawn, panting.

The security fence grew with the settlement; more generally, the history of the deepening divisions between Israelis and Palestinians is the history of the settlement movement. At first, there was nothing. The bare, dusty earth was uninterrupted, and the thorny bushes, cypresses, and olive trees continued to grow undisturbed between the city, the wadi, and the settlement. Only the different building styles separated us from our neighbors, as we looked across at each other with curiosity and hostility

Then the coils of barbed wire appeared, stretching along the hill, climbing on top of each other, creating a thick division. Back then, the barbed-wire fence was low, not yet prominent. Through the wire, the exposed earth was visible. One day, the barbed-wire fence was raised, supported on metal piles, and a regular metal fence was erected beneath it.

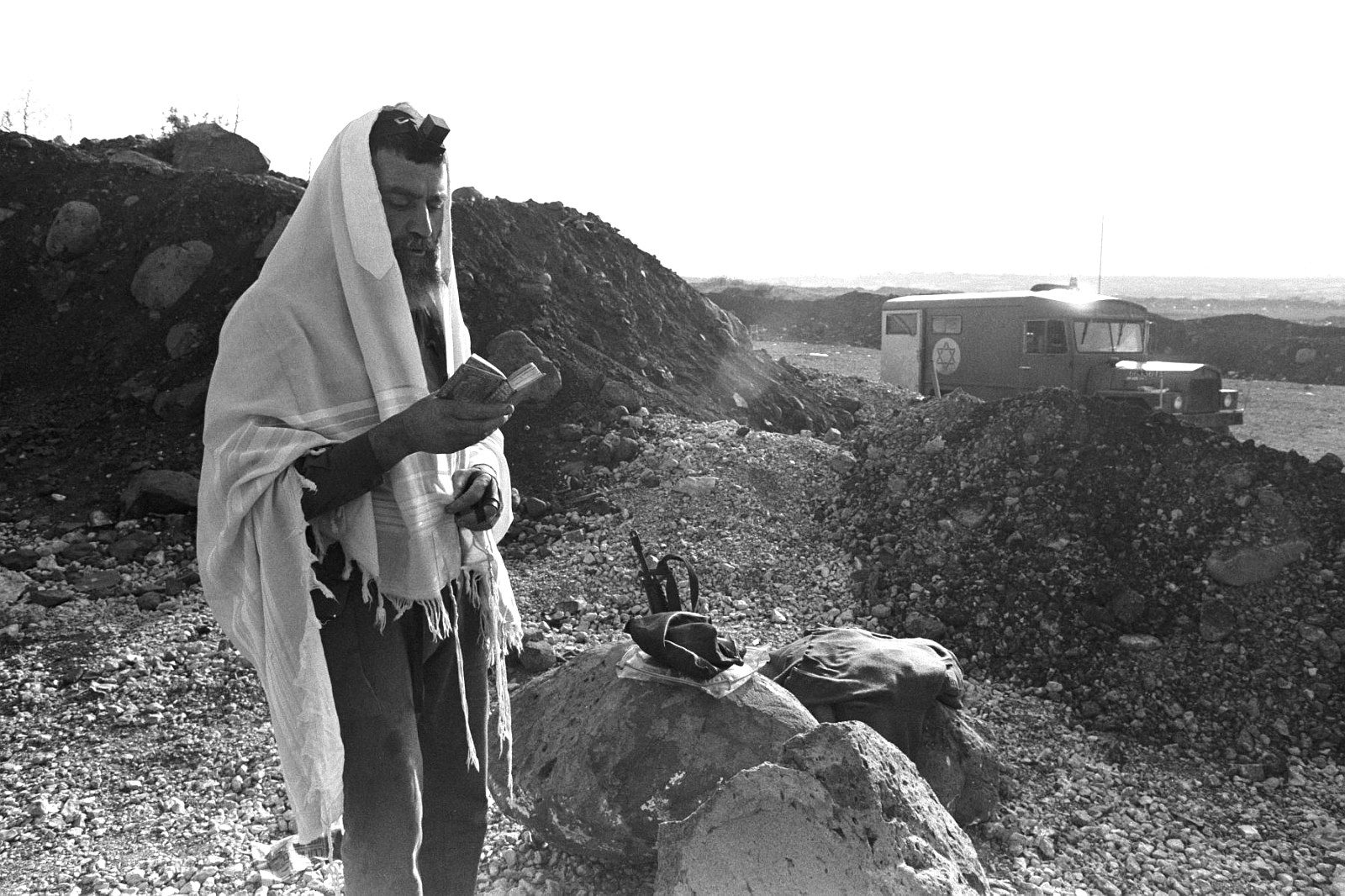

The soldiers’ watchtowers were added soon after. Composed of square concrete structures, the soldiers surveyed the surrounding hills: an ambulance driving along a dirt road, children wandering in the wadi searching for something in the sparse grass, a few figures exiting one of the houses and walking toward the main road, cars flashing by toward the checkpoints into Jerusalem.

Today, an electric fence surrounds the settlement I grew up in. As the fence grew, so did the fear. As it became more sophisticated, the imagination became more sophisticated, and the images of danger it provided became more complex and extreme. As the fence grew and intensified, the people on the other side of it became less familiar, more dangerous, more threatening. A fence does not remove a threat, nor does it eliminate it. It only serves to make the imagination work harder.

I think we were curious and wanted, deep within our small bodies, to get closer to the vendors in front of the mosque. It never happened.

At the center of the settlement, as in any Jewish town, was the synagogue. All paths led to it, like arteries to a beating heart. The synagogue was solitary in its magnificent appearance, clumsy and heavy, almost overwhelming in size. Stained glass decorated the windows, artwork adorning one of its walls—the only artwork in the settlement, since in a synagogue art was not perceived as competing with religion’s monopoly on self-expression and spiritual creation. It was a work by a local, a painter born in the Soviet Union, who always looked as if he had ended up in this small settlement unwillingly, so far from the cultural center of Moscow. Once, I tried to talk to him after Sabbath prayers, to find out what he read (Hemingway), what he listened to (jazz), what his spiritual and artistic world consisted of. He backed away from me in a panic, his gaze suspicious, his eyes moving quickly while he muttered, as if ashamed, the answers to my questions.

The synagogue was divided into different quarters, like a dense city with several neighborhoods. To the right of the Holy Ark and near the wall sat all the small-business owners, hardworking people with entrepreneurial spirit, whose business initiatives had inexplicably made them less devout. Perhaps it was due to the constant friction within the world of finance, or perhaps it was due to their (relative) economic comfort. In the rows close to the left and right of the stage, where the cantor stood and where the Torah was placed, sat those who could be called the central pillars of the settlement—yeshiva graduates, rabbis, those who moved along the fringes of the rabbinical world, educators and teachers, and employees in important institutions, like bank workers and lawyers and a few academics. These were the ones who remained for the rabbi’s lessons and who engaged in political and philosophical discourse. To their left were the marginal residents of the settlement. These included immigrants from the former Soviet Union, and those who had not progressed in the settlement’s housing hierarchy and remained in the original housing unit they were provided with. They entered and exited the synagogue in silence, hardly spoke inside, and hardly spoke outside either. They did not mix socially, and they did not assimilate into settlement life. Perhaps they were wary of others, carrying old scars from a closed and crowded society.

A fence does not remove a threat, nor does it eliminate it. It only serves to make the imagination work harder.

From the synagogue, you could turn in two directions. On the one hand, the settlements were open to wild, untamed nature. If you left the synagogue and went down to the left, you got your first view of the Judean Hills. On clear days, especially after rain had washed the desert air, you could glimpse the Dead Sea—a motionless silver platter, almost a frozen lake in the middle of the desert. On exceptional days, rare but precious, you could see the Mountains of Edom, huge red cliffs that crumbled downward toward the Dead Sea. The Judean Desert and Dead Sea marked the edge of this vista.

If you left the shul and went in another direction, though, there was an expansive view of Palestinian villages or cities. Settling on hills with views over the villages was often defined as a “security” consideration, revealing how much the security establishment was a key partner in the settlement enterprise and how much it directed and guided the points on the map of land settlement (in this sense, one can think of the settlers as being in constant, unending security service). Every settlement has a side toward which shame or dread is felt, and a side to which the breath and gaze are drawn. This struggle is the struggle of the settlement enterprise: the intense desire for normalcy, to be in a place that blends peacefully with the world around it; and yet the constant glance over the shoulder, toward the unfamiliar, toward a language you don’t know and therefore cannot be part of, nor do you want to be.

In that same gaze, curiosity and attraction, calm and apprehension existed together. As we looked at the open desert landscape, we were constantly forced to look over our shoulder as well. The soul of the settlement was this duality.

Every settlement has a side toward which shame or dread is felt, and a side to which the breath and gaze are drawn.

After darkness took over, the merry sounds of weddings on the Palestinian side sometimes echoed across the valley. We could see the smoke of bonfires and hear the plaintive songs of the singers. These weddings carried, into the settlement, sounds that inexplicably combined mass joy with a clear and piercing yearning. The pacing of celebrations that lasted a week, the fact that they intensified every night to a new peak of revelry and musical joy, all this stood in contrast to the settlement’s way of conducting itself, with its concentrated, quick, measured celebrations. Even if one could find intoxication of the senses and a measure of liberation, it was only for one evening. The music that wafted between the hills offered another possibility, but it was incomprehensible to us. The sounds awakened something within us, but the language that carried across the wadi was not one we knew.

On Friday afternoons, meanwhile, there was a more recognizable noise: that of cheering fans in Ramallah’s soccer stadium, reaching us, the settlement children, as we played soccer ourselves, with the same degree of passion and dedication. These sounds pierced the languid atmosphere of erev Shabbat on the settlement, as the adults busied themselves cooking and cleaning in preparation for dinner. What we heard from over the valley signified something unspoken: that normal events were taking place in Ramallah, events that had nothing to do with us. This was autonomy in its most primary sense. Moreover, with an irony that only reality could provide, a reversal occurred: we, who saw ourselves at the center, became the periphery; we had a small soccer field full of cracks, while Ramallah had a large soccer stadium made of concrete, with benches, spectators, and grass. This role reversal was confusing, undermining a sense of scorn we had begun to develop toward the neighboring city.

Sometimes, in that vast brown and gold landscape, there would appear in the sky a colorful kite. Kites are just a children’s pastime, but in the narrow strip between Ramallah and the hilltops where we lived, they took on another significance. It was a cause for celebration when we suddenly saw a kite that had floated over into the settlement, vibrant and spectacular, moving nobly through the air, looking for a place to land. The first child to reach it would be the winner, and so all the children of the settlement would stop what they were doing and run. I can still recall a large group of sweating children, some with sidelocks and others holding their kippahs in their hands, chasing after that artifact of childhood from the other side.

Once we had the kite, we admired its different colors, and tried to understand its construction, the types of paper that created such strong wings, the elaborate knots we could never untangle. We were mere guests in a space in which the kite was the oldest resident, and although we never spoke about who truly belonged to this landscape, there was something about those kites that provided the answer.

One can think of the settlers as being in constant, unending security service.

Today, years after leaving the settlement and the Orthodox way of life, and fifty years after the founding of the Gush Emunim movement, my perspective has changed. My childhood in the settlement—which was full of encounters with that beautiful environment—is forever besmirched with the blood and despair of aggression, lack of compassion, and defensive barriers.

A few days ago, I picked up Albert Camus’s Return to Tipasa. I read his words on the Algiers of his childhood and youth, when Algeria was a colony of France. I read of his desire to return to that particular light, to the unique scent of the sea, to the place where he sat facing an open horizon and fragrant air, and felt he was in the heart of light. I read and thought about Psagot, the settlement in which I grew up, about the archaeological site next to the settlement with the stone altar and ancient olive press, about the view that stretches as far as the Dead Sea and Edomite mountains. This will always be the place where I encountered the most light. I used to sit there at sunset and sunrise, scanning the horizon, dreaming of the journeys and freedom I later found in my twenties. This was when I also first glimpsed the settlements from the outside—saw the unity of thought, the power and the violence, the disregard for neighbors and religious ideas which, unlike the emotional storm at the beginning of the journey, had already become cold and rigid, arrogant and fossilized.

Will we succeed in retelling the story of Judaism, of Zionism, of Israel? I believe in migration, I believe in leaving one place for another, I believe in rebelling against one reality for the sake of another. This is what the founders of Zionism and the state believed in. This is what Kook believed in. He also succeeded: look at all these hills with growing families. But the time has come to return to that room where Kook paced back and forth at midnight, searching for words that would charge reality with change, with progress, with good.

What began with a few restless young people in Ukraine, Poland, and Russia, what became necessary after World War II, needs a new beginning. Spirit and not land, generosity and not power, life and not death, kites and not stones.