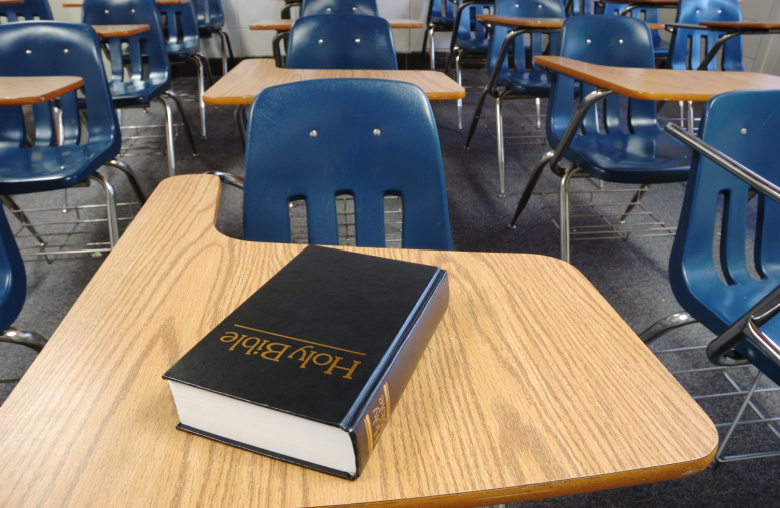

As two Supreme Court cases decided this term demonstrate, white evangelicals want both religious schools funded by the state and religion in public schools—and the Supreme Court’s (Catholic) majority is eager to assist. The goal is religion-state consolidation, not separation. This development is not accidental; it is the result of decades of attacks on the Establishment Clause in the service of white conservative Christian power.

In 1985, in Wallace v. Jaffree, the Supreme Court determined that the purpose of an Alabama statute authorizing school prayer was “to endorse religion,” which rendered it unconstitutional. To arrive at this decision, the court applied the “Lemon test.” This was a 3-prong evaluation that assessed a law’s purpose (religious or secular), its effect (to advance/inhibit religion or not), and the degree of religion-government entanglement (a lot or a little).

Not everyone agreed back then. In his dissent, then-Justice William Rehnquist made a plea: eliminate the Lemon test. He also told a story: his history of the Establishment Clause. It was more correct, he asserted, than the “mistaken understanding of constitutional history” documented in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the first case in which the Supreme Court “incorporated” the First Amendment’s religion clauses—that is, applied them to state laws. And Rehnquist formulated an argument: “The ‘wall of separation between church and State’ is a metaphor based on bad history,” he wrote. It is “a metaphor which has proved useless as a guide to judging. It should be frankly and explicitly abandoned.”

Last week, in Kennedy v. Bremerton, Justice Neil Gorsuch made good on Rehnquist’s desire: the Lemon test is no more. More precisely, Gorsuch contended, “this Court long ago abandoned Lemon and its endorsement test offshoot.” In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor questioned this claim, pointing out that the majority merely “infers Lemon’s implicit overruling.”

But Kennedy was about far more than a test. It’s an acidic assault on the Establishment Clause and the very idea of separation of church and state. Combined with the recent decision in Carson v. Makin, these rulings effectively dissolve decades of Supreme Court jurisprudence on religion. As legal scholars Ira Lupu and Robert Tuttle put it, “the Court has jettisoned the entire post-World War II constitutional project of maintaining a secular state.” The wall of separation has come tumbling down.

In Carson v. Makin, a 6-3 majority ruled that Maine must fund private religious schools through its secondary school tuition program. Chief Justice John Roberts laid out the following rule: if a state program is open to any private secular institutions, it must also be open to private religious institutions. In fact, excluding religious schools, even if the goal is to maintain state disestablishment, is “discrimination against religion.”

Roberts likes to diminish the import of his radical decisions. In 2017’s Trinity Lutheran (state funding for church playgrounds), 2020’s Espinoza (tax credits for private religious school scholarships), and now Carson (tuition for private religious schools), he has consistently framed opinions requiring states to include churches and religious schools in their state funding programs as “unremarkable.” Trinity Lutheran, he claimed, was just about “playground resurfacing.” Likewise, he minimizes the repercussions of Carson. The decision doesn’t force Maine to abandon secular public education or require it to fund private religious schools, he reasons. It simply instructs the state to decide if it can provide rural public education (it cannot) and, if not, fund the religious schools families select.

That some may use religious tenets to exclude students and families that public schools must serve does not matter. The handbook for Bangor Christian Schools, one of the schools involved in Carson, reminds students and families that “attendance…is a privilege, not a right.” Indeed, families are expected to align with their values, including not getting divorced except in cases of adultery; students can be expelled for “immoral activities” or being transgender. But so long as the money is ostensibly passed through an individual decision-maker such as a parent, public money flowing to religious institutions is, in Roberts’ world, no big deal. The state is merely supporting a student going to school, not the school. Laundered through “choice,” taxpayer dollars lose the scent of the state and any whiff of religious establishment.

In his dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer underscores that this is a major, not minor, doctrinal shift: “We have never previously held what the Court holds today, namely, that a State must (not may) use state funds to pay for religious education as part of a tuition program designed to ensure the provision of free statewide public school education.” He warns, “What happens once ‘may’ becomes ‘must’?” For her part, Justice Sonia Sotomayor reminds us that she flagged the problem five years ago in Trinity Lutheran: the court’s majority “was ‘lead[ing] us…to a place where separation of church and state is a constitutional slogan, not a constitutional commitment.’”

Kennedy centered on a public high school football coach and his decision to pray—visibly, vocally, publicly—after games. The distortion of facts in this case was pervasive, so much so that an appellate judge called it a “deceitful narrative.” Sotomayor included photographs in the dissent to underscore that “the record before us…tells a different story” than the coach and his lawyers did.

Prior to last week, the Supreme Court had understood the Establishment Clause as prohibiting audible prayer in classrooms (Engel, 1962 and Schempp, 1963), moments of silence dedicated to prayer in classrooms (Jaffree, 1985), ceremonial prayer at graduations (Lee, 1992), and at student-led prayer at sporting events (Santa Fe, 2000). None of these cases prohibited truly private worship — the inward, personal, silent kind of prayer that no one even knows is happening. But all of these decisions resisted prayer, whether overtly sectarian or generically spiritual, that created an appearance of government endorsement or a semblance of government coercion.

Now, Gorsuch tells us that, “learning how to tolerate speech or prayer of all kinds is ‘part of learning how to live in a pluralistic society.’” But this Gorsuchian toleration only goes one way: those who feel uncomfortable amidst visible, loud, and possibly coercive public prayer bear the burden of toleration. A coach who wants to pray aloud on the 50-yard-line immediately after a game cannot possibly be asked to find another space, out of earshot and sight lines of students, for that would be “censorship and suppression,” or what Roberts labels “discrimination against religion” in Carson.

Having neutered Lemon as an irreparable test of Establishment Clause violations, Gorsuch proffers “historical practices and understanding” or “history and tradition” as the new metric. What guidance the past creates for the present is murky at best.

Whatever the standard, the core logic of Carson and Kennedy is clear: free exercise claims eclipse establishment concerns. But all free exercise claims are not created equal, and not all religious groups receive such deference. In the recent past, perceptions of persecution by white conservative Christians, what longtime Supreme Court reporter Linda Greenhouse characterized as “grievance conservatives,” have gained traction while the rights of religious minorities and others have diminished.

To be fair, it would be inaccurate to say only white conservative Christians support the outcomes in Carson and Kennedy. In March 2021, the Council of Islamic Schools and the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of American joined with the Catholic Partnership for Inner-City Education to file an amicus brief encouraging the Court to take the case and reverse the lower court’s ruling allowing Maine to exclude private religious schools. These different religious traditions, the amici wrote, share a commitment to integrating faith and education, recognize there are substantial financial costs to religious education, and therefore view exclusion from the tuition assistance program as discrimination.

Pepperdine law professor Michael A. Helfand, who co-authored an amicus brief for the Orthodox Union, celebrated Carson. “With all forms of religious exclusions now constitutionally prohibited,” he wrote, “religious communities can rest assured new funding programs will not provide for the general public while excluding them.” Or so Carson makes it seem; but this decision will not transfer a significant amount of money to Muslim or Jewish schools. The Orthodox Union knows the money is not in Maine; they’re hoping that advocacy in states like New York and Florida, which have significantly larger Jewish populations and many Jewish schools, could bolster state support for Jewish schools.

This is where things get messy. The potential upside—state money to offset high private school tuition—appears desirable for fierce advocates of private Jewish day schools. But it is also a fig leaf. Not only is it unlikely to net significant sums, but it is short-sighted and plays into the hands of the white conservative Christians who sees religious minorities as temporary allies who can easily be discarded when no longer useful.

The Carson–Kennedy matrix is a package deal: it dismantles the Establishment Clause by funding private religious schools and sanctions public school environments as uncomfortable spaces for religious minorities. This is intentional. The easiest way to avoid being offended by Kennedy’s prayers is to be elsewhere. While Gorsuch insists the public has to tolerate Kennedy, the families that direct tuition assistance to sectarian schools don’t have to tolerate “prayer of all kinds.” They have the court’s blessing to isolate and to shield themselves from encountering difference.

The court has amplified the power of private religious schools to create their own sequestered spaces, governed by only their rules. Over the past decade, religious school employees—frequently women—have learned they have few rights and little recourse when they quarrel with their employers. This is because another pair of cases, Hosanna-Tabor (2012) and Our Lady of Guadalupe (2020), allows schools to call almost anyone a “minister” regardless of title, training, or job duties. And once someone is a minister, the “ministerial exception” insulates religious schools from most employment discrimination claims.

The one-two punch of Carson and Kennedy arises not only from the elevation of white conservative Christianity, but also in goading religious minorities to support funding private religious schools by making public schools hostile spaces. When religious minorities embrace public money for their own private schools, they provide ample cover for white conservative Christians to decimate secular public education and, more broadly, to reject public schools as a common good. This is a dangerous path for a pluralistic society.

Ronit Y. Stahl is associate professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley and a Greenwall Foundation Faculty Scholar in Bioethics. She is the author of the award-winning Enlisting Faith: How the Military Chaplaincy Shaped Religion and State in Modern America.