On December 7, 1972, some five hours and 18,000 miles away from the Earth, traveling at more than 16,000 feet per second on the outbound leg of the Apollo 17 mission to the moon, astronaut Harrison H. Schmitt pointed a 70-millimeter Hasselblad Data Camera back at the Earth and—though the crew was not scheduled to take pictures—snapped a photo.

The image, labeled by NASA as AS17-148-22727 but better known as The Blue Marble, would become the most reproduced photograph in history. After the film returned to Earth, the image would grace the front page of nearly every world newspaper.

The shot is stunning: a planet bathed in sunlight, no trace of humanity, only swirling white clouds, the greens and browns of Africa, the sands of the Arabian Peninsula, the bright Antarctic ice, a cyclone spinning off India, the deep ocean blue, a world at once vast and vulnerable, so very exposed, only a thin slip of atmosphere separating it from the cold dark of space.

The map was made visible, almost comprehensible. Giant abstractions (continents, oceans, seas, and gulfs) could be taken in at a glance; puzzle pieces clicked into place, proof the familiar schoolbook view was right all along. And yet at such a remove, the sum becomes far greater than its parts. The effect: something close to awe. One glimpse, a flood of wonderment—be it religious, spiritual, emotional, scientific, philosophical, intellectual, utopian, what have you. Choose your own sublime. A succinct and simple statement: Spaceship Earth, beautiful, alone. The mystery of our place in the cosmos.

Take a long view of 1972: Terrorists take and kill hostages at the Munich Olympics. On Bloody Sunday, soldiers shoot unarmed protesters in Derry, while Bloody Friday bombs go off across Belfast, as the Troubles consume Northern Ireland. President Ferdinand Marcos puts the Philippines under martial law. An earthquake in Nicaragua kills thousands and displaces many more. A Uruguayan airplane goes down in the Andes, leaving survivors to eat their own dead. In the U.S., White House operatives are arrested for breaking into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate complex. Floods kill hundreds in South Dakota’s Black Hills. A deadly hurricane slams the East Coast—the costliest to date. In St. Louis, the first troubled buildings of the once-promising Pruitt-Igoe housing development are demolished, an event dubbed “the day modern architecture died.” Two New York City cops are shot and killed in the East Village, part of ongoing racial unrest. A Delta flight from Detroit to Miami gets hijacked to Algeria. In Georgia, sculptors finish carving the figures of three Confederate leaders—Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis, and Robert E. Lee—onto the granite face of Stone Mountain, now the biggest bas-relief sculpture in the world. Wernher von Braun, the so-called father of rocket science, retires from NASA, after its budget is slashed, and takes a job at a private aerospace company.

The Blue Marble photo has been credited for everything from spurring the environmental movement (behold our fragile planet) to fueling the counterculture to furthering globalization (no borders, no boundaries) to raising human consciousness and encouraging a new way of seeing. In The New York Times, The Blue Marble ran above the fold on Christmas Eve, sandwiched between stories about youth and heroin, radicals bombing Fifth Avenue department stores, and the headline “Heavy Raids Go On for Seventh Day in North Vietnam.” A flash of hope at the end of a very bleak year.

On my computer, I listen to Apollo 17 tapes and watch the mission videos. The first day on the surface, when his fellow moonwalker encourages him to pause his work and admire the view of their home planet floating in the dark above the lunar valley wall, Schmitt, the busy geologist, deadpans, “Eh, you seen one Earth, you’ve seen ’em all.” But a few days before, less than an hour after he took what might be the most famous photo in history, the spaceman reported to Mission Control, “I’ll tell you, if there ever was a fragile-appearing piece of blue in space, it’s the Earth right now.” Some four decades after that, over lunch in an Albuquerque restaurant, Schmitt will tell me the experience of being on the moon was far more than he ever anticipated: “No matter how many conversations you’ve had with others who have done it, it’s like standing on the rim of the Grand Canyon for the first time.”

The Blue Marble photo has been credited for everything from spurring the environmental movement to fueling the counterculture to furthering globalization to raising human consciousness and encouraging a new way of seeing.

Consider the astronauts of Apollo 14, a year before The Blue Marble was taken, trudging uphill through moondust that clings to the legs of their bulky suits, dragging behind them a rickshaw full of equipment that leaves glinting tracks in the sun. The expedition—the second of two scheduled for the mission—had been assiduously planned. The two men were taking the first long walk on the moon, hoping to travel more than three times farther from their ship than previous crews. They carried finely gridded maps to help them traverse the surface. For years, government cartographers—including many in St. Louis—had used aerial and astronomical imagery to create stunningly detailed lunar charts, atlases, globes, slides, models, and even a flying simulator that early astronauts trained on.

The landing of Apollo 14 had been the most precise to date—less than one hundred feet from the target on the map. But things were different on the ground. In the crystalline light and dark of the lunarscape—no atmospheric haze, just a bright, monotonous undulation of pockmarked gray rubble—distances collapsed, objects seemed to disappear. Their objective: walk about three quarters of a mile to the rim of the vast Cone Crater and collect a rock sample. But looking around, the spacemen couldn’t find the landmarks on their maps.

Well, where do you think we are? . . . Where are you? . . . Right behind you . . . That crater is that crater right up there. That crater is the crater over to the left of it . . . Where do you think B is? . . . I think B’s the one we just passed; back there where we were talking . . . All right . . . Doggone it, you can sure be deceived by slopes here. The sun angle is very deceiving . . . Yup. It’s going to take longer than we expected. Our positions are all in doubt now . . . We’ve got a ways to go yet . . . I don’t think we’ll have time to get there . . . Oh, let’s give it a whirl. Gee whiz. We can’t stop without looking into Cone Crater. We’ve lost everything if we don’t get there.

The confused astronauts argue over their position, with Mission Control no help at all. Photos show a spaceman staring at his map. In danger of exhausting their air, water, and strength, the men will never make it to the crater. At one point during the grueling hike, Houston tells them to just count the spot they’re standing on as the rim. The astronauts press on—calling the controllers “finks”—but eventually they’ll have to give up, take what samples they can, and double back. All this way and they’ll never get the view.

They will, at least, bring back a four-billion-year-old rock that contains a tiny fragment of Earth from around the time when the moon was ejected—via a collision with another celestial object or objects—from our still-molten planet. Our earliest piece of history, a bit of what became the Earth flung out onto what was becoming the moon. Those traces, however, won’t be discovered for nearly fifty years.

So maybe it is to cheer himself up that four hours, thirty-four minutes, and forty-one seconds after exiting the hatch—wrapping up a frustrating trek of nearly two miles—one of the astronauts takes out a six iron and slices two golf balls into the lunar dark, then shuts himself and his partner into the module for good, lifts up to dock with the command capsule, called Kitty Hawk, and heads the roughly 240,000 miles home.

“I’ll tell you, if there ever was a fragile-appearing piece of blue in space, it’s the Earth right now.”

Perhaps it wasn’t surprising the men lost their way; humans had only been flying for sixty-seven years, since the Wright Brothers took off. An aerial photograph of the Apollo 14 landing site—with the round trip to the giant crater marked with a thin squiggly line—is almost comical. The moon men had no idea they’d gotten so close—perhaps just fifty feet from the rim.

Space philosopher Frank White calls the cognitive shift, or sudden clarity, that supposedly comes from seeing the Earth from above the “overview effect.” A transcendent epiphany upon beholding the big picture, a mind-altering sense of belonging, coherence, togetherness, and compassion, the effect has been reported by astronauts of all nationalities over the decades.

Even the earthbound have sought the higher mind. In early 1966, a twenty-seven-year-old Bay Area impresario named Stewart Brand took one hundred micrograms of LSD, climbed a three-story San Francisco roof, looked to the horizon, and beheld—or so it seemed—the planet curving away from him. That day he became fixated on a question, which he scrawled in his notebook: Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the entire Earth yet? Soon after, Brand began petitioning NASA—along with members of Congress, Soviet scientists, U.N. officials, and luminaries like Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller—to release a picture of the planet from space. He was convinced it would blow humanity’s mind. As part of his campaign, he made buttons, showed up on college campuses, and stood on the street in a Day-Glo sandwich board. (A cohort of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, Brand was known to put on music and art happenings.)

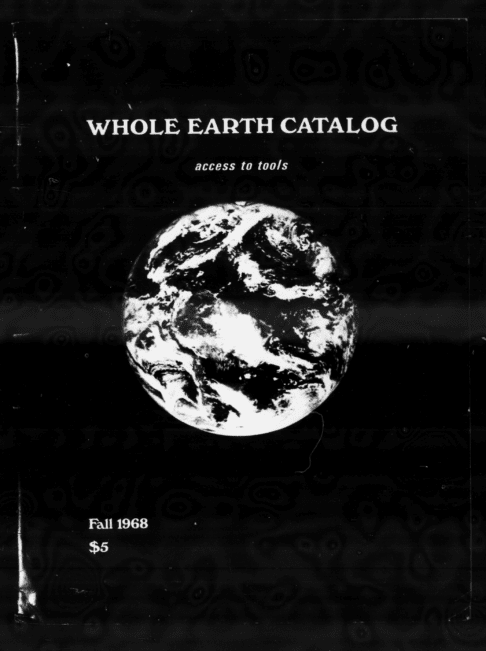

The next year, NASA released a color image from a weather satellite, a photo Brand slapped onto the oversized cover of what would become the 1968 countercultural bible—part overstuffed yellow pages, part philosophical almanac, part how-to hippie manual—known as The Whole Earth Catalog. The bestselling series would win a National Book Award. Decades later, in a documentary about his life, Brand recalls, “It was a hopeful image, and it blew away the mushroom cloud.”

“Is it inhabited?” they said to each other and laughed—and then they did not laugh. What came to their minds a hundred thousand miles and more into space—“halfway to the moon” they put it—what came to their minds was the life on that little, lonely, floating planet, that tiny raft in the enormous, empty night. “Is it inhabited?”

—Poet and playwright Archibald MacLeish on the Apollo 8 astronauts’ first flight around the moon, in 1968, during which they took the famous Earthrise photograph, showing a pale half-Earth rising above the lunar surface

My uncle, a child of the space race who grew up fascinated with rocketry, kept a poster of the Earthrise photo in his bedroom, even as an adult living in his childhood home. After he died, my parents left it up, long after his room was used for guests. Deep-sea explorer William Beebe—who was also an early aviator, an aerial photographer, and a friend of Teddy Roosevelt—believed celestial observatories should be mounted on churches and prisons, for the betterment of those within. He came up with the idea of outfitting toothbrushes with tiny telescopes, so that everyone—by law—might contemplate the cosmos for a few minutes at night.

From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, “Look at that, you son of a bitch.”

—Astronaut Edgar Mitchell, 1971

A rat done bit my sister Nell.

(with Whitey on the moon)

Her face and arms began to swell.

(and Whitey’s on the moon)

I can’t pay no doctor bill.

(but Whitey’s on the moon)

Ten years from now I’ll be payin’ still.

(while Whitey’s on the moon)—Gil Scott-Heron, “Whitey on the Moon,” 1970

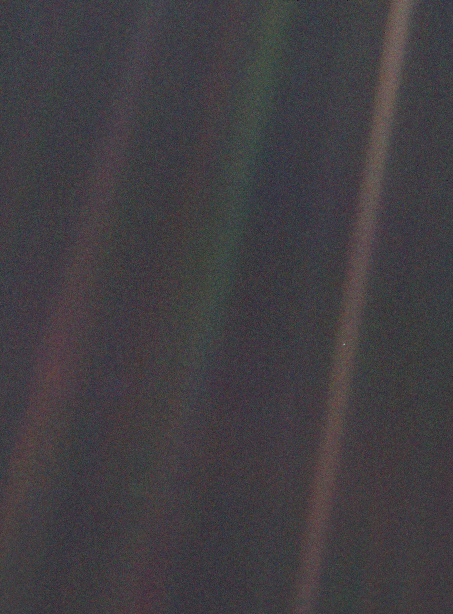

I am not so sure politics recedes with distance. In fact, taking a look at the “big picture” can be a power move, a bid for unearned authority. That said, there is one image that never fails to upset the humdrum baseline of my mouth-breathing day-to-day: the Pale Blue Dot, taken from four billion miles away on February 14, 1990, minutes before the Voyager 1 probe finally shut down its cameras, as it (still sailing) would not pass anything else in its lifetime. A valentine to our cosmic insignificance, how we look to a machine made by our hands and flung deep into the unknown: a fleck of galactic dust afloat on sweeping bands of scattered light. There’s no way you’d see us—just a single pixel—if you didn’t know where to look. Lost. Puny. Meaningless. If I stare too long, the bottom drops out. Existential vertigo. (I, a middle schooler, am in the photo, along with everyone I know or care about, and everyone else on the planet.) The picture took nearly three months to travel to Earth. Now Voyager is nearly four times farther away. Light from it would take about a day to reach us. And still the probe—the most distant manmade object—flies on, sending back data and carrying its golden record inscribed with laughter, voices, music, and birdsong into the faint hum of interstellar space.

This might seem a bit wifty, but research suggests that cultivating a sense of awe can make us more humble, healthy, happy, and generous. Our thinking sharpens. We become less materialistic, more likely to cooperate, sacrifice, and share. We care more deeply about others. Our wounds begin to heal. (Awe attends injuries both physical and psychic—the emotion has been associated with lowered inflammation and recovery from PTSD.) Feeling awestruck inspires patience—it lengthens our sense of time. In one study, simply reading a story about surveying Paris from atop the Eiffel Tower left participants more satisfied with their lives.

Schmitt’s singular view—the whole Earth, lit by the sun—has not been seen since by human eyes. (Though astronauts might catch another glimpse in the coming weeks, when the Artemis mission hopes to fly a lap around the moon.) Forty years after Schmitt’s photograph, NASA released another picture of the whole planet, titled Blue Marble 2012. Despite appearances, the photo didn’t offer a singular view. It was a fake, or composite, stitched together from multiple shots taken on a single day by a satellite orbiting only 500 miles above the Earth. To actually see such a sight, one would need to be nearly 8,000 miles away. The impossible photo was far sharper, however, and—unlike the original Blue Marble—centered the Western Hemisphere.

In the 1972 photo, Africa also appears “upside-down,” though the picture is usually printed to show the more familiar orientation.

How else has our view shifted since 1972? The same year that NASA updated its Blue Marble, an astronaut floating outside the International Space Station turned his camera away from Earth and back on himself. The #space #selfie went viral. In the shot, the planet is perfectly framed in the reflection of his visor but almost entirely obscured by his hands, the camera, and part of the station. In other words, it’s more self than space. The photo still makes the rounds on social media. Maybe the selfie is the opposite of the long view.

Or maybe they’re one and the same. For who can forget that nineteenth-century American astronomer Percival Lowell, whose work would lead to the discovery of Pluto, also published detailed maps of canals on Mars, strange markings on Mercury, and a series of “spokes” across Venus that were ultimately revealed—in 2003—to be nothing more than the reflection (in the telescope lens) of the blood vessels in his eyes? Poring over pages and pages of painstaking drawings, Lowell couldn’t spot the obvious truth staring back at him: onto each planet he’d projected his own eyeball. The moral here is so literal. We often look out and see only ourselves.

While somewhat slippery to define, awe is a separate emotion, and comes complete with its own responses—bodily, mentally, chemically—than, say, joy or surprise. Studies show it dampens shame and self-criticism. (The self shifts into perspective, as we briefly slip the bonds of narcissism.) Being struck with awe is something we can practice, improve our capacity for wonder. Take a nature walk. Dance in a group. Behold the kindness of others. This all sounds right, if a bit easier said than done, though I’m caught by a less optimistic footnote to the research—that a quarter of encounters with awe involve a sense of threat. Replace the flower with a tornado, the grasping newborn with scenes from a genocide. It turns out awe often carries an undercurrent of fear.

A final haunting Earth-view, a flight of imagination from well before an Apollo mission ever lifted off. In 1947, two years after the debut of the atomic bomb and five years after he voluntarily entered himself into a Japanese American internment camp in the Arizona desert, the artist Isamu Noguchi sculpted a simple figure in sand atop a square of wood. A shadowy photograph was taken from above—giving the appearance of distance—then the model destroyed. The unrealized earthwork, Sculpture To Be Seen From Mars, was to be a kind of celestial cenotaph: a ten-mile-long abstraction of a human face (a flattop mound for a forehead, a giant gaping circle as a mouth, two cone eyes, and the nose a pyramid stretching a mile high) raised in the desert and meant to be seen from space—a memorial to a civilization that had long since done itself in.